C:\WINDOWS\TEMP\Brief SC84856 TWIST App's Sub.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invincible Jumpchain- Compliant CYOA

Invincible Jumpchain- Compliant CYOA By Lord Statera Introduction Welcome to Invincible. Set in the Image comic book multiverse, this setting is home to older heroes and villains like Spawn, The Darkness, and The Witchblade. This story, however, focuses on the new superhero Invincible (Mark Grayson), the half-breed Viltrumite-Human hybrid and son of the world famous hero Omni-Man (Nolan Grayson). Invincible spends the beginning of his career working alongside the Teen Team, and with his father, to defend not only Baltimore but the Earth from many and varied threats. Little does he know that his father, rather than being an alien from a peace loving species, is actually a harbinger of war to the planet Earth. Viltrumites are actually a race bent on conquering the universe, one planet at a time. And with their level of power, not much can stop them. Fortunately, there is one secret the Viltrumite Empire has been hiding. Over 99% of the Viltrumite population had been wiped out using a plague genetically engineered by scientists of the Coalition of Planets, they are forced to wage a proxy war using their servant races against the Coalition, all the while sending individual Viltrumites out to take one world at a time, in their attempt to conquer the stars. As humans are the closest genetic match for the Viltrumite race outside of another Viltrumite, the remnants of this mighty alien race turn their sights on Earth in the hopes of using it as a breeding farm to repopulate their race. To help you survive in this universe, here are 1000 Choice Points. -

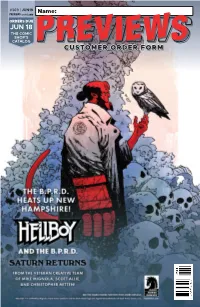

Jun 18 Customer Order Form

#369 | JUN19 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE JUN 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Jun19 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:08:57 PM June19 Humanoids Ad.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:15:02 PM SPAWN #300 MARVEL ACTION: IMAGE COMICS CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN/SUPERMAN #1 DC COMICS COFFIN BOUND #1 GLOW VERSUS IMAGE COMICS THE STAR PRIMAS TP IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN VS. RA’S AL GHUL #1 DC COMICS BERSERKER UNBOUND #1 DARK HORSE COMICS THE DEATH-DEFYING DEVIL #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS #1000 MARVEL COMICS HELLBOY AND THE B.P.R.D.: SATURN RETURNS #1 ONCE & FUTURE #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BOOM! STUDIOS Jun19 Gem Page.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:24:56 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Bad Reception #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Flash: Crossover Crisis Book 1: Green Arrow’s Perfect Shot HC l AMULET BOOKS Archie: The Married Life 10 Years Later #1 l ARCHIE COMICS Warrior Nun: Dora #1 l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars: Rey and Pals HC l CHRONICLE BOOKS 1 Lady Death Masterpieces: The Art of Lady Death HC l COFFIN COMICS 1 Oswald the Lucky Rabbit: The Search for the Lost Disney Cartoons l DISNEY EDITIONS Moomin: The Lars Jansson Edition Deluxe Slipcase l DRAWN & QUARTERLY The Poe Clan Volume 1 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Cycle of the Werewolf SC l GALLERY 13 Ranx HC l HEAVY METAL MAGAZINE Superman and Wonder Woman With Collectibles HC l HERO COLLECTOR Omni #1 l HUMANOIDS The Black Mage GN l ONI PRESS The Rot Volume 1 TP l SOURCE POINT PRESS Snowpiercer Hc Vol 04 Extinction l TITAN COMICS Lenore #1 l TITAN COMICS Disney’s The Lion King: The Official Movie Special l TITAN COMICS The Art and Making of The Expance HC l TITAN BOOKS Doctor Mirage #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT The Mall #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 2 World’s End Harem: Fantasia Volume 1 GN l GHOST SHIP My Hero Academia Smash! Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Kingdom Hearts: Re:Coded SC l YEN ON Overlord a la Carte Volume 1 GN l YEN PRESS Arifureta: Commonplace to the World’s Strongest Zero Vol. -

Rattus Libri

Ausgabe 149 Mitte Juli 2016 Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, liebe Kolleginnen und Kollegen, in unserer etwa zwölf Mal im Jahr erscheinenden Publikation möchten wir Sie über interessante Romane, Sachbücher, Magazine, Comics, Hörbücher und Filme aller Genres informieren. Gastbeiträge sind herzlich willkommen. RATTUS LIBRI ist als Download auf folgenden Seiten zu finden: http://rattus-libri.taysal.net/ www.beam-ebooks.de/kostenlos.php http://blog.g-arentzen.de/ www.foltom.de www.geisterspiegel.de/ www.literra.info www.phantastik-news.de http://phantastischewelt.wordpress.com/ Ältere Ausgaben unter: www.light-edition.net www.uibk.ac.at/germanistik/dilimag/ Einzelne Rezensionen erscheinen bei: www.buchrezicenter.de; www.sfbasar.de; www.filmbesprechungen.de; www.phantastiknews.de; http://phantastischewelt.wordpress.com; www.literra.info; www.rezensenten.de; www.terracom- online.net. Das Logo hat Lothar Bauer für RATTUS LIBRI entworfen: www.saargau-blog.de; www.saargau-arts.de; http://sfcd.eu/blog/; www.pinterest.com/lotharbauer/; www.facebook.com/lothar.bauer01. Das Layout hat Irene Salzmann entworfen. Für das PDF-Dokument ist der Acrobat Reader 6.0 erforderlich. Diesen erhält man kostenlos bei: www.adobe.de. Die Rechte an den Texten verbleiben bei den Verfassern. Der Nachdruck ist mit einer Quellenangabe, einer Benachrichtigung und gegen ein Belegexemplar erlaubt. Wir bedanken uns vielmals bei allen Autoren und Verlagen, die uns Rezensionsexemplare und Bildmaterial für diese Ausgabe zur Verfügung stellten, und den fleißigen Kollegen, die RATTUS LIBRI und die Rezensionen in ihren Publikationen einbinden oder einen Link setzen. Nun aber viel Vergnügen mit der Lektüre der 149. Ausgabe von RATTUS LIBRI. Mit herzlichen Grüßen Ihr RATTUS LIBRI-Team Seite 1 von 84 Rubriken_______________________________________ _______ Schwerpunktthema: Artikel: Die faszinierende Welt der Spiele (Teil 1) mit Rezensionen ................................ -

Media Industry Approaches to Comic-To-Live-Action Adaptations and Race

From Serials to Blockbusters: Media Industry Approaches to Comic-to-Live-Action Adaptations and Race by Kathryn M. Frank A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Lisa A. Nakamura Associate Professor Aswin Punathambekar © Kathryn M. Frank 2015 “I don't remember when exactly I read my first comic book, but I do remember exactly how liberated and subversive I felt as a result.” ― Edward W. Said, Palestine For Mom and Dad, who taught me to be my own hero ii Acknowledgements There are so many people without whom this project would never have been possible. First and foremost, my parents, Paul and MaryAnn Frank, who never blinked when I told them I wanted to move half way across the country to read comic books for a living. Their unending support has taken many forms, from late-night pep talks and airport pick-ups to rides to Comic-Con at 3 am and listening to a comics nerd blather on for hours about why Man of Steel was so terrible. I could never hope to repay the patience, love, and trust they have given me throughout the years, but hopefully fewer midnight conversations about my dissertation will be a good start. Amanda Lotz has shown unwavering interest and support for me and for my work since before we were formally advisor and advisee, and her insight, feedback, and attention to detail kept me invested in my own work, even in times when my resolve to continue writing was flagging. -

A Matter of Inches My Last Fight

INDEPENDENT PUBLISHERS GROUP A Matter of Inches How I Survived in the Crease and Beyond Clint Malarchuk, Dan Robson Summary No job in the world of sports is as intimidating, exhilarating, and stressridden as that of a hockey goaltender. Clint Malarchuk did that job while suffering high anxiety, depression, and obsessive compulsive disorder and had his career nearly literally cut short by a skate across his neck, to date the most gruesome injury hockey has ever seen. This autobiography takes readers deep into the troubled mind of Clint Malarchuk, the former NHL goaltender for the Quebec Nordiques, the Washington Capitals, and the Buffalo Sabres. When his carotid artery was slashed during a collision in the crease, Malarchuk nearly died on the ice. Forever changed, he struggled deeply with depression and a dependence on alcohol, which nearly cost him his life and left a bullet in his head. Now working as the goaltender coach for the Calgary Flames, Malarchuk reflects on his past as he looks forward to the future, every day grateful to have cheated deathtwice. 9781629370491 Pub Date: 11/1/14 Author Bio Ship Date: 11/1/14 Clint Malarchuk was a goaltender with the Quebec Nordiques, the Washington Capitals, and the Buffalo Sabres. $25.95 Hardcover Originally from Grande Prairie, Alberta, he now divides his time between Calgary, where he is the goaltender coach for the Calgary Flames, and his ranch in Nevada. Dan Robson is a senior writer at Sportsnet Magazine. He 272 pages lives in Toronto. Carton Qty: 20 Sports & Recreation / Hockey SPO020000 6.000 in W | 9.000 in H 152mm W | 229mm H My Last Fight The True Story of a Hockey Rock Star Darren McCarty, Kevin Allen Summary Looking back on a memorable career, Darren McCarty recounts his time as one of the most visible and beloved members of the Detroit Red Wings as well as his personal struggles with addiction, finances, and women and his daily battles to overcome them. -

Marketing Violent Entertainment to Children Report

MARKETING VIOLENT ENTERTAINMENT TO CHILDREN: A REVIEW OF SELF-REGULATION AND INDUSTRY PRACTICES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, MUSIC RECORDING & ELECTRONIC GAME INDUSTRIES REPORT OF THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION SEPTEMBER 2000 Federal Trade Commission Robert Pitofsky, Chairman Sheila F. Anthony Commissioner Mozelle W. Thompson Commissioner Orson Swindle Commissioner Thomas B. Leary Commissioner TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................1 A. President’s June 1, 1999 Request for a Study and the FTC’s Response ........................................................1 B. Public Concerns About Entertainment Media Violence ...................1 C. Overview of the Commission’s Study ..................................2 Focus on Self-Regulation ...........................................2 Structure of the Report .............................................3 Sources .........................................................4 II. THE MOTION PICTURE INDUSTRY SELF-REGULATORY SYSTEM .......4 A. Scope of Commission’s Review ......................................5 B. Operation of the Motion Picture Self-Regulatory System .................6 1. The rating process ..........................................6 2. Review of advertising for content and rating information .........8 C. Issues Not Addressed by the Motion Picture Self-Regulatory System .......10 1. Accessibility of reasons for ratings ............................10 2. Advertising placement -

Original / Powersurge IMAGE Banshee

NOTES CARDS WITH LINKS TO PICS (BLUE), FOLLOWED BY THOSE LISTED IN BOLD ARE HIGHEST PRIORITY I NEED MULTIPLES OF EVERY CARD LISTED, AS WELL AS PACKS, DECKS, UNCUT SHEETS, AND ENTIRE COLLECTIONS Original / Powersurge IMAGE Banshee - Character 5 Multipower Power Card Black Cat - Femme Fatale 8 Anypower Card Cyclops - Remove Visor 6 Anypower + 2 Basic Universe (Power Blast - Spawn) Ghost Rider - Hell on Wheels Any Character's - Flight, Massive Muscles, & Super Speed Human Torch - Character Artifacts (Linkstone, Myrlu Symbiote, The Witchblade) Iceman - Character Backlash - Mist Body Iron Man - Character Brass - Armored Powerhouse & Weapons Array Jubilee - Prismatic Flare Curse - Brutal Dissection Juggernaut - Battering Ram Darkness - Demigod of the Dark Rogue - Mutant Misslile Events - Witchblade on the Scene Scarlet Witch - Hex Power & Sorceress Slam (Non-Error) Grifter - Nerves of Steel Grunge - Danger Seeker IQ Killrazor - Outer Fury Any Hero - Power Leech Malebolgia - Character & Signed in Blood Apocalypse - Character Overtkill - One-Man Army Bishop - Character & Temporal Anomaly Ripclaw - Character & Native Magic Cable - Character & Askani' Son Shadowhawk - Backsnap & Brutal Revenge Carnage - Anarchy Spawn - Protector of the Innocent Deadpool - Don't Lose Your Head! Stryker - Armed and Dangerous Doctor Doom - Character & Diplomatic Immunity Tiffany - Character & Heavenly Agent Dr. Strange - Character Velocity - Internal Hardware, Quick Thinking, & Speedthrough Iron Man Character Violator - Darklands Army Ghost Rider - Character Voodoo -

IV. Fabric Summary 282 Copyrighted Material

Eastern State Penitentiary HSR: IV. Fabric Summary 282 IV. FABRIC SUMMARY: CONSTRUCTION, ALTERATIONS, AND USES OF SPACE (for documentation, see Appendices A and B, by date, and C, by location) Jeffrey A. Cohen § A. Front Building (figs. C3.1 - C3.19) Work began in the 1823 building season, following the commencement of the perimeter walls and preceding that of the cellblocks. In August 1824 all the active stonecutters were employed cutting stones for the front building, though others were idled by a shortage of stone. Twenty-foot walls to the north were added in the 1826 season bounding the warden's yard and the keepers' yard. Construction of the center, the first three wings, the front building and the perimeter walls were largely complete when the building commissioners turned the building over to the Board of Inspectors in July 1829. The half of the building east of the gateway held the residential apartments of the warden. The west side initially had the kitchen, bakery, and other service functions in the basement, apartments for the keepers and a corner meeting room for the inspectors on the main floor, and infirmary rooms on the upper story. The latter were used at first, but in September 1831 the physician criticized their distant location and lack of effective separation, preferring that certain cells in each block be set aside for the sick. By the time Demetz and Blouet visited, about 1836, ill prisoners were separated rather than being placed in a common infirmary, and plans were afoot for a group of cells for the sick, with doors left ajar like others. -

Violent Comic Books and Perceptions of Ambiguous Provocation Situations

MEDIAPSYCHOLOGY, 2, 47–62. Copyright © 2000, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Violent Comic Books and Perceptions of Ambiguous Provocation Situations Steven J. Kirsh Paul V. Olczak Department of Psychology State University of New York-Geneseo This study investigated the effects of reading very violent versus mildly violent comic books on the interpretation of ambiguous provocation situations, independent of trait hostility. 119 introductory psychology students read either a violent comic book, Curse of the Spawn, or a mildly violent comic book, Archie & Friends. After reading the comic books, participants read six short stories in which a child caused a negative event to happen to another child, but the intent of the peer causing this negative event was ambiguous. After each story, participants were asked a series of questions about the harmdoer’s intent, potential retaliation toward the harmdoer, and about the harmdoer’s emotional state. Responses were coded in terms of amount of negative and violent content. Results indicate that those male participants reading the violent comic books responded more negatively on the ambiguous provocation story questions than male participants reading the mildly violent comic books. For females, responding was primarily governed by trait hostility. These data suggest that hostile attributional bias may be influenced by gender, trait hostility, and exposure to violent media. Over the past two decades, voluminous research has focused on media influences (e.g., television, video games) on aggression. These studies consistently find that exposure to violent themes in media is significantly related to aggressive behavior and thoughts (Anderson, 1997, Berkowitz, 1984, Cesarone, 1998). An additional, yet understudied, source of media violence to which individuals are frequently exposed is comic books. -

Spawn Origins: Volume 20 Free

FREE SPAWN ORIGINS: VOLUME 20 PDF Danny Miki,Angel Medina,Brian Holguin,Todd McFarlane | 160 pages | 04 Mar 2014 | Image Comics | 9781607068624 | English | Fullerton, United States Spawn (comics) - Wikipedia This Spawn series collects the original comics from the beginning in new trade paperback volumes. Launched inthis line of newly redesigned and reformatted trade paperbacks replaces the Spawn Collection line. These new trades feature new cover art by Greg Capullo, recreating classic Spawn covers. In addition to the 6-issue trade paperbacks, thi… More. Book 1. Featuring the stories and artwork by Todd McFarla… More. Want to Read. Shelving menu. Shelve Spawn Origins, Volume 1. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Rate it:. Book 2. Featuring the stories and artwork by Spawn creator… More. Shelve Spawn Origins, Volume 2. Book 3. Spawn Origins: Volume 20 Spawn Origins, Volume 3. Book 4. Todd McFarlane's Spawn smashed all existing record… More. Shelve Spawn Origins, Volume Spawn Origins: Volume 20. Book 5. Featuring the stories and artwork by Todd Mcfarla… More. Shelve Spawn Origins, Volume 5. Book 6. Shelve Spawn Origins, Volume 6. Book 7. Spawn survives torture at the hands of his enemies… More. Shelve Spawn Origins, Volume 7. Book 8. Shelve Spawn Origins, Volume 8. Book 9. Journey with Spawn as he visits the Fifth Level of… More. Shelve Spawn Origins, Volume 9. Book Cy-Gor's arduous hunt for Spawn reaches its pinnac… More. Shelve Spawn Spawn Origins: Volume 20, Volume Spawn partners with Terry Fitzgerald as his plans … More. The Freak returns with an agenda of his own and Sa… More. -

MUNDANE INTIMACIES and EVERYDAY VIOLENCE in CONTEMPORARY CANADIAN COMICS by Kaarina Louise Mikalson Submitted in Partial Fulfilm

MUNDANE INTIMACIES AND EVERYDAY VIOLENCE IN CONTEMPORARY CANADIAN COMICS by Kaarina Louise Mikalson Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia April 2020 © Copyright by Kaarina Louise Mikalson, 2020 Table of Contents List of Figures ..................................................................................................................... v Abstract ............................................................................................................................. vii Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... viii Chapter 1: Introduction ....................................................................................................... 1 Comics in Canada: A Brief History ................................................................................. 7 For Better or For Worse................................................................................................. 17 The Mundane and the Everyday .................................................................................... 24 Chapter outlines ............................................................................................................. 30 Chapter 2: .......................................................................................................................... 37 Mundane Intimacy and Slow Violence: ........................................................................... -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Spawn #8 by Alan Moore Spawn #8 by Alan Moore

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Spawn #8 by Alan Moore Spawn #8 by Alan Moore. Newsstand version has UPC code, printed on cheaper newsprint and is missing the 2 page pull-out poster in the centerfold. The Newsstand version is only 36 pages rather than 40 pages. Awards 1994 - Eisner Award - Best Writer - Alan Moore - Nominated This issue is a variant of Spawn (Image, 1992 series) #8 [Direct]. [no title indexed] (Table of Contents) Spawn / cover / 1 page (report information) in Spawn (Juniorpress, 1996 series) #2 (1996) in Spawn (Infinity Verlag, 1997 series) #4 ([Juli] 1997), #4 ([Juli] 1997) in Spawn - Origem (Pixel Media, 2007 series) #2 (março 2008) in Spawn Origins Collection (Image, 2010 series) #1 (March 2010) in Spawn: Edición Integral (Planeta DeAgostini, 2010 series) #1 (Junio 2010) Indexer Notes. Cover art is an homage to the cover of Spider-Man (Marvel, 1990 series) #1 (August 1990) Brian K Vaughan Won Alan Moore Gen 13 Auction – And Is Giving It Away. A few weeks ago, Bleeding Cool told you that Scott Dunbier was auctioning off an unpublished Gen-13 script by Alan Moore to help pay the medical bills of comic book creator Bob Wiacek . And it seems that in a hotly contested auction, it was Brian K Vaughan , co-creator o f Y The Last Man and Saga who was victorious at a bid of $3433 for the faxed pages. But he's not keeping it to himself. On Instagram he wrote; Happy Friday, scrollers! Recently, legendary comics creator Bob Wiacek (who inked some of my favorite images ever, including the cover to Uncanny X-Men 210, easily the most badass thing my 10-year-old self had ever seen) has been dealing with some costly health issues.