Title Children Reading Series Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Production 2019.Xlsm

CustomEyes® Book List Title Author ISBN RRP Publisher Age Synopsis Mr and Mrs Brick are builders, just like their mothers and fathers and grandmothers and grandfathers. But their new baby doesn’t seem to be following in their footsteps. Instead of building things up, she keeps Happy Families - Miss Brick the Builders' Ahlberg, Allan 9780140312423 £4.99 Puffin 06+ knocking things down! Baby Miss Josie Jump the jockey can’t wait to gallop in a race like her mum, her brother and even her grandma, but everyone says she’s too young. But then grandma’s horse gets a sore throat and Jimmy Jump gets a Happy Families - Miss Jump the Jockey Ahlberg, Allan 9780140312416 £4.99 Puffin 06+ splinter in his bottom Mr Biff is a boxer but he likes to eat cream cakes and sit by the fire in his slippers. Mr Bop is a boxer too, but he’s the fittest, toughest man in town. So Mr Biff needs to train hard before their charity match – but will he Happy Families - Mr Biff the Boxer Ahlberg, Allan 9780140312362 £4.99 Puffin 06+ strong enough to swap his cream cakes for carrots? Mr Buzz works hard to look after his bees - and his bees work hard to make lots and lots of lovely honey. But one morning Mr Buzz sees his bees swarming and he knows that when bees swarm and buzz off together Happy Families - Mr Buzz the Beeman Ahlberg, Allan 9780140312447 £4.99 Puffin 06+ they never come back. So the Buzz family put on their bee hats and bee gloves and give chase. -

UK@Kidscreen Delegation Organised By: Contents

© Bear Hunt Films Ltd 2016 © 2016 Brown Bag Films and Technicolor Entertainment Services France SAS Horrible Science Shane the Chef © Hoho Entertainment Limited. All Rights Reserved. ©Illuminated Films 2017 © Plug-in Media Group Ltd. UK@Kidscreen delegation organised by: Contents Forewords 3-5 KidsCave Entertainment Productions 29 David Prodger 3 Kidzilla Media 30 Greg Childs and Sarah Baynes 4-5 Kindle Entertainment 31 Larkshead Media 32 UK Delegate Companies 6-53 Lupus Films 33 Accorder Music 6 MCC Media 34 Adorable Media 7 Mezzo Kids 35 Animation Associates 8 Myro, On A Mission! 36 Blink Industries 9 Blue-Zoo Productions 10 Ollie’s Edible Adventures/MRM Inc 37 Cloth Cat Animation 11 Plug-in Media 38 DM Consulting 12 Raydar Media 39 Enabling Genius 13 Reality Studios 40 Eye Present 14 Serious Lunch 41 Factory 15 Sixth Sense Media 42 Film London 16 Spider Eye 43 Fourth Wall Creative 17 Studio aka 44 Fudge Animation Studios 18 Studio Liddell 45 Fun Crew 19 The Brothers McLeod 46 Grass Roots Media 20 The Children’s Media Conference 47 History Bombs Ltd 21 The Creative Garden 48 HoHo Rights 22 Three Arrows Media 49 Hopster 23 Thud Media 50 Ideas at Work 24 Tiger Aspect Productions 51 Illuminated Productions 25 Tom Angell Ltd 52 ITV PLC 26 Visionality 53 Jellyfish Pictures 27 Jetpack Distribution 28 Contacts 54 UK@Kidscreen 2017 3 Foreword By David Prodger, Consul General, Miami, Foreign and Commonwealth Office I am delighted to welcome such an impressive UK delegation to Kidscreen which is taking place in Miami for the third time. -

The Edinburgh International Book

IMAGINATION RUNS WILD RBS SCHOOLS PROGRAMME 22–30 AUGUST 2011 Book online at: http://schools.edbookfest.co.uk Download this brochure at www.edbookfest.co.uk OUR THANKS TO SPONSORS & SUPPORTERS Sponsor of the Schools Programme RBS is committed to the education and development of the next generation and we are proud to be associated with one of Edinburgh’s most prestigious festivals. As sponsors of the Schools Gala Day, Transport Fund and Schools Programme RBS recognises the importance of encouraging schools, pupils and teachers to connect with the world of books through participation, imagination and creation. rbs.com/community With additional And supported by: Thanks also go to: support from: The Binks Trust Ernest Cook Trust Cruden Foundation Design: Tangent Graphic Origami: Morica Yan WELCOME TO THE B O O K F E S T I V A L’ S 2011 RBS SCHOOLS PROGRAMME… HOW TO USE OUR CLASSROOM IDEAS A visit to the Book Festival can be an exciting experience - especially for those pupils who wouldn’t normally have the chance - as well as a good starting point for lesson planning. Classroom Ideas, included with each event, have been coded by subject area to help you choose the activities best suited to your needs. They are labelled with subject headings according to the relevant experiences and outcomes of the Curriculum for Excellence: EXPRESSIVE ARTS: - ART & DESIGN DOWNLOAD A COPY OF - DRAMA THIS BROCHURE FROM - MUSIC www.edbookfest.co.uk - PARTICIPATION IN PERFORMANCE LANGUAGES: - LITERACY & ENGLISH SOCIAL STUDIES: If you do want to make your visit a core part of - PEOPLE, PLACE & ENVIRONMENT classroom activities, you will find suggestions - PEOPLE, PAST EVENTS & SOCIETIES beside each event as to how the author’s visit and their books can be used in topic work. -

Horrible Science World Presents

Horrible Science World Presents: Excellent Experiments and Awesome Activities. The following experiments and activities are taken from the ‘Horrible Science’ series of books published by Scholastic, and are divided into the different Zones that the character Billy Miller visits in the Birmingham Stage Company play ‘Horrible Science’. The journey Billy goes on through Horrible Science World in order to understand science is a good way of introducing the subject of scientific enquiry. Only by developing his knowledge, skills and understanding is Billy able to survive Horrible Science World and save the day. This often involves investigation and trying things out (eg: pushing the button before pulling the lever to control gravity in the Gravitarium) and collaboration (Eg: Billy and the scientists working together to make a circuit.) This is further underlined by the involvement of the audience throughout the play – he needs our help as co-collaborators and co-learners if he’s going to triumph. Links can be made across the scenes in the play to encourage creative thinking (Eg1: the fact that bacteria live inside us is introduced by the Big Bacteria, and then picked up again in Frankenstein’s Lab, as the reason we get stomach gas. Eg2: metal being a good conductor and used in the circuit in Act 1 makes it a potentially dangerous material inside the Thuderdome) The activities and experiments for each zone contain an introduction suggesting further links with the play, and suggestions for how they could be used in helping pupils discover more behind the science in the story. The Fatal Forces Zone Physical processes. -

Monthly Quiz List March 2015 1 of 10 Q Uiz # Q U Iz Typ E Fictio N Title A

Monthly Quiz List March 2015 Reading Practice (RP) Quizzes Quiz # Type Quiz Fiction Title Author ISBN Publisher Interest Level Pts Book Level Series 227853 RP F Claude on the Slopes Alex T. Smith 978-1-4449-0930-2 Hodder Children's Books LY 0.5 4.9 Claude 227668 RP F The Witch's Dog Frank Rodgers 978-0-14-038466-6 Puffin LY 0.5 2.9 Colour Young Puffin A Rainbow Shopping Day (Early 226001 RP F Vivian French 978-1-4440-0517-2 Orion Children's Books LY 0.5 2.5 Early Reader (Orion) Reader) 228092 RP N Amazing Pets Anne Rooney 978-1-4451-3050-7 Franklin Watts LY 0.5 2.1 Edge 228103 RP N World's Toughest Anne Rooney 978-1-4451-3035-4 Franklin Watts LY 0.5 2.6 Edge 228068 RP F Today I Will Fly! Mo Willems 978-1-4063-3848-5 Walker Books LY 0.5 0.5 Elephant and Piggie 228066 RP F My Friend Is Sad Mo Willems 978-1-4063-3847-8 Walker Books LY 0.5 0.7 Elephant and Piggie 228067 RP F There Is a Bird on Your Head! Mo Willems 978-1-4063-4824-8 Walker Books LY 0.5 1 Elephant and Piggie 228024 RP F Frankie vs. the Pirate Pillagers Frank Lampard 978-0-349-00162-3 Little, Brown & Co. LY 1 3.8 Frankie's Magic Football 228028 RP F Frankie vs. the Cowboy's Crew Frank Lampard 978-0-349-00159-3 Little, Brown & Co. LY 1 3.9 Frankie's Magic Football Frankie vs. -

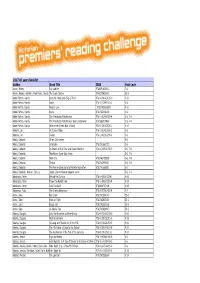

FINAL 2017 All Years Booklist.Xlsx

2017 All years Booklist Author Book Title ISBN Year Level Aaron, Moses Lily and Me 9780091830311 7-8 Aaron, Moses (reteller); Mackintosh, David (ill.)The Duck Catcher 9780733412882 EC-2 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Does My Head Look Big in This? 978-0-330-42185-0 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Jodie 978-1-74299-010-1 5-6 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Noah's Law : 9781742624280 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Rania 9781742990188 5-6 Abdel-Fattah, Randa The Friendship Matchmaker 978-1-86291-920-4 5-6, 7-8 Abdel-Fattah, Randa The Friendship Matchmaker Goes Undercover 9781862919488 5-6, 7-8 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Where the Streets Had a Name 978-0-330-42526-1 9-10 Abdulla, Ian As I Grew Older 978-1-86291-183-3 5-6 Abdulla, Ian Tucker 978-1-86291-206-9 5-6 Abela, Deborah Ghost Club series 5-6 Abela, Deborah Grimsdon 9781741663723 5-6 Abela, Deborah In Search of the Time and Space Machine 978-1-74051-765-2 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah Max Remy Super Spy series 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah New City 9781742758558 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah Teresa 9781742990941 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah The Remarkable Secret of Aurelie Bonhoffen 9781741660951 5-6 Abela, Deborah; Warren, Johnny Jasper Zammit Soccer Legend series 5-6, 7-8 Abrahams, Peter Behind the Curtain 978-1-4063-0029-1 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Down the Rabbit Hole 978-1-4063-0028-4 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Into The Dark 9780060737108 9-10 Abramson, Ruth The Cresta Adventure 978-0-87306-493-4 3-4 Acton, Sara Ben Duck 9781741699142 EC-2 Acton, Sara Hold on Tight 9781742833491 EC-2 Acton, Sara Poppy Cat 9781743620168 EC-2 Acton, Sara As Big As You 9781743629697 -

LBHS Non-Adopted Reading List

NON-ADOPTED READING LIST 2020-2021 The following is a list of non-adopted suggested readings for Lemon Bay High School students. Teachers of particular courses may be requiring the entire class to read one or more of the books listed under that course, or be using the book as supplementary material. However, if a student or parent objects to the content of a particular book that the class is reading, the parent may contact the teacher to request that alternate reading materials be utilized for his/her student. Should you have any questions about the appropriateness of reading materials in any course taken by your student, please contact the teacher or administration. Language Arts 1,000 Places to See Before You Die 1984 2gether 4ever 7 Habits of Highly Effective Teens 911 Report, The A Bend in the River A Country Doctor A Day No Pigs Would Die A Doll’s House A Girl Named Disaster A God of Small Things A Lesson Before Dying A Midsummer Night’s Dream A Passage to India A Raisin in the Sun A Separate Peace A Streetcar Named Desire A Tale of Two Cities A Thousand Splendid Suns A Town Like Alice A Walk to Remember A Yellow Raft in Blue Water Abba to Zoom Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Alas, Babylon Alias Grace Alice in Wonderland All In Almost Perfect America’s Dumbest Criminals Among the Brave Among the Hidden An Actor Prepares An Edgar Allan Poe Reader Andy Warhol Maus: A Survivor’s Tale Animal Farm Anna Karenina Anne Frank Remembered Anthem Midwife's Apprentice, The Artemis Fowl Artemis Fowl– Eternity Code -

Murderous Maths Guaranteed to Mash Your Mind: More Muderous Maths Pdf

FREE MURDEROUS MATHS GUARANTEED TO MASH YOUR MIND: MORE MUDEROUS MATHS PDF Kjartan Poskitt,Philip Reeve | 160 pages | 04 Aug 2008 | Scholastic | 9781407105871 | English | London, United Kingdom The original MURDEROUS MATHS Book Log in or Register. Suitable for 8 - 12 years. To help you find what you're looking for, see similar items below. More books for 8 - 12 year olds. OK, so here you are. More Murderous Maths! But beware! Kjartan Murderous Maths Guaranteed to Mash Your Mind: More Muderous Maths in York with Murderous Maths Guaranteed to Mash Your Mind: More Muderous Maths wife and four children. He regularly performs at venues all over the country. Philip Reeve was born and raised in Brighton, where he worked in a bookshop for years while also producing and directing a number of no-budget theatre projects. Philip then began illustrating and has since provided cartoons and jokes for around forty books, including the best-selling Scholastic series Horrible Historiesas well as Murderous Maths and Dead Famous. Mortal Engines defies easy categorisation. It is a gripping adventure story set in an inspired fantasy world, where moving cities trawl the globe. A magical and unique read, it immediately caught the attention of readers and reviewers and won several major awards. Philip has also written Buster Baylissa series for younger readers, and stand alone novels including Here Lies Arthurwhich won the Carnegie Medal. Philip lives in Devon with his wife and son and his interests are walking, drawing, writing and reading. Menu Browse. Account actions Log in or Register. Basket 0 items. Enlarge cover. -

Horrible Science of Everything Kindle

HORRIBLE SCIENCE OF EVERYTHING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nick Arnold,Tony De Saulles | 96 pages | 01 Mar 2010 | Scholastic | 9781407115498 | English | London, United Kingdom Horrible Science of Everything PDF Book What happens when you drop a rabbit through the centre of the earth? Sales across the series now stand at over an amazing one and half million books! This book was a piece of cake when I read it. Each episode also features a famous scientist being interviewed by either Mark or McTaggart. This book is the best. Basket 0 items. Taking a journey from the very small, to the very big, readers are taken on a tour of everything in science from the smallest thing ever to the horribly huge universe. Russell Chee rated it liked it Feb 11, Evaluation: I rated this book 4 stars because it is a very informative book that puts otherwise confusing scientific concepts into simple explanations. He soon have a new series to his name called Wild Lives, about the first year in animals life, first up Nick will be looking at lions and sharks! Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Cancel Save settings. The perfect book for any 12 year old, I read it at around the same age. This article contains very little context, or is unclear to readers who know little about the book. Welcome back. The choices you make here will apply to your interaction with this service on this device. What makes things explode? More Details More books for 8 - 12 year olds. Mark arrives at the studio with terrible stomach pains and asks the Shrinking Scientists to find out what is wrong with him. -

7Th and 8Th Grade Summer Reading

Name: _________________________ 7th and 8th Grade Summer Reading Students will be required to read one fiction and one nonfiction book this summer. When they return to school, they will be required to complete a book report regarding each of the books they read. All books are available for purchase through amazon.com. Most books are available through the Kindle app. Also, many of these books are available to borrow from New Haven Public Libraries. Take selfies with your summer reading book and email them to me over the summer. I should be able to see the book in the picture. Every student who sends me a reading selfie will be entered into a raffle to win a $20 gift card to Amazon! My email address is [email protected]. Please include the name of the book in your email. List the books you read on the attached form. Have your parent sign it to participate in a Jepson school- wide summer reading celebration at the beginning of the school year. Fiction Book Suggestions to Read this Summer (You can read any fiction book you’d like, these are just some ideas) ***Future 8th Graders – May of you enjoyed reading the The Lightning Thief. The author, Rick Riodan, wrote may other books about Percy Jackson (including Sea of Monsters, The Titan’s Curse, and The Battle of the Labyrinth) as well as other books like The Lightning Thief which include themes of Greek Mythology including the Heroes of Olympus series or House of Hades. Read them if you enjoyed The Lightning Thief! Title, Author, Lexile Description Absolutely Normal “A summer journal? I don’t know what a journal is! This is going to be boring.” That’s Chaos what Mary Lou Finney thinks, anyway. -

Year 7 Maths

Year 7 Maths Murderous Maths by Poskitt Kjartan Nearly all the answers to nearly all the questions about everything in Maths! The Math Inspectors 1: The Case of The Claymore Diamond by Daniel Kenney and Emily Boever Four friends start a detective agency in the first in this funny mystery series. Includes bonus questions! The Man Who Counted: A Collection of Mathematical Adventures by Malba Tahan An Arabian Nights-style compilation of the adventures of a mathematician who uses his powers to settle disputes and overcome enemies and in the process wins fame and fortune. Science Corpse Talk Scientists by Adam Murphy and Lisa Murphy. History and science explored with interviews with great scientists from the past such as Galileo, Archimedes and Mary Anning. Blood Bones and Body Bits by Nick Arnold and Tony De Saulles. Horrible Science explores the human body to gruesome effect. Chemical Chaos by Nick Arnold and Tony De Saulles Discover the history of some ground breaking experiments (and those that went horribly wrong) and try some at home! Frightening Light by Nick Arnold and Tony De Saulles From lasers to phosphorescence, become enlightened on this illuminating subject! History A Million Years in a Day by Greg Jenner Described as Horrible Histories for grown- ups, this accessible book uses the framework of a typical day to describe how our ancestors lived The Book of Boy by Catherine Gilbert Murdock Set in the 1350s, just after the Plague devastates Europe, this is the story of Boy, a hunchbacked goatherd who sets off on a quest with a mysterious stranger. -

OPEN YOUR MIND Bishop Vesey's Grammar School Supra-Curriculum Booklet

OPEN YOUR MIND Bishop Vesey's Grammar School supra-curriculum booklet It is what you read when you don’t have to that determines what you will be when you can’t help it – Oscar Wilde It is what you read when you don’t have to that determines what you will be when you can’t help it. –Oscar Wilde Open Your Mind Introduction – A note from the Editor……………………. Dear student, At Bishop Vesey’s Grammar School, we aspire to foster in our students a love of learning. We also aim at to provide appropriate support and challenge for our students in order for them to fulfil their potential. Super-Curriculum encapsulates all those activities that nurture academic enquiry beyond the measurable outcomes of examination results. We also know that potential future universities and employers will be interested and impressed by the initiative taken by students who have eng aged with super-curricular activities. Engaging in super curricular activities will help students develop a love for their favourite subject or subjects. Included in this booklet are a collection of ‘subject pages’, which have been designed by Academic Departments at BVGS, which include a variety of prompts and ideas, which will enable you to explore your favourite subjects beyond the confines of the taught syllabus. These ‘subject pages’ are by no means exhaustive lists but should offer students a source of inspiration to explore their favourite subjects. These activities can take many forms including wider reading, watching online materials, d ownloading podcasts, attending University lectures/masterclasses, arranging Summer School placements, engaging with H.E ‘super - curricular’ initiatives or visiting museums/places of academic interest.