Fishery Circular

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 35 • NUMBER 166 Wednesday, August 26,1970 • Washington, D.C

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 35 • NUMBER 166 Wednesday, August 26,1970 • Washington, D.C. Pages 13563-13634 Agencies in this issue— The President Agricultural Research Service > Agriculture Department Civil Aeronautics Board Consumer and Marketing Service Customs Bureau Farmers Home Administration Federal Communications Commission Federal Insurance Administration Federal Power Commission Fish and Wildlife Service Food and Drug Administration General Services Administration Internal Revenue Service Interstate Commerce Commission Land Management Bureau Maritime Administration Mines Bureau National Highway Safety Bureau National Transportation Safety Board Securities and Exchange Commission Small Business Administration Tariff Commission Wage and Hour Division Detailed list of Contents appears inside. Announcing First 10-Year Cumulation TABLES OF LAWS AFFECTED in Volumes 70-79 of the UNITED STATES STATUTES AT LARGE Lists all prior laws and other Federal in public laws enacted during the years 1956- struments which were amended, repealed, 1965. Includes index of popular name or otherwise affected by the provisions of acts affected in Volumes 70-79. Price: $2.50 Compiled by Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration Order from Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 1 1 aHf» D IT f’IC T rO Published dally, Tuesday through Saturday (no publication on Sundays, Mondays, or ■ ■ H r iir^ l I t i l on toe day after an official Federal holiday), by the Office of the Federal Register, National $ Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, Washington, D.C. 20408, Area Code 202 Phone 962-8626 pursuant to the authority contained in the Federal Register Act, approved July 26, 1935 (49 Stat. -

Florida Best and Brightest Scholarship ACT Information on ACT Percentile

Florida Best & Brightest Scholarship ACT Information on ACT Percentile Rank In light of the recent Florida legislation related to Florida teacher scores on The ACT, in order to determine whether a Florida teacher scored “at or above the 80th percentile on The ACT based upon the percentile ranks in effect when the teacher took the assessment”, please refer to the following summary. 1. The best evidence is the original student score report received by the teacher 2. If a teacher needs a replacement score report, a. Those can be ordered either by contacting ACT Student Services at 319.337.1270 or by using the 2014-2015 ACT Additional Score Report (ASR) Request Form at http://www.actstudent.org/pdf/asrform.pdf . Reports for testing that occurred prior to September 2012 have a fee of $34.00 for normal processing and can be requested back to 1966. b. The percentile ranks provided on ASRs reflect current year norms, not the norms in effect at the time of testing. c. The following are the minimum composite scores that were “at or above the 80th percentile” at the time of testing based upon the best available historical norm information from ACT, Inc.’s archives. For the following test date ranges: • September, 2011 through August, 2016 : 26 • September, 1993 through August, 2011 : 25 • September, 1991 through August, 1993 : 24 • September, 1990 through August, 1991 : 25 • September, 1989 through August, 1990 : 24 • September, 1985 through August, 1989 : 25 • September, 1976 through August, 1985 : 24 • September, 1973 through August, 1976 : 25 • September, 1971 through August, 1973 : 24 • September, 1970 through August, 1971 : 25 • September, 1969 through August, 1970 : 24 • September, 1968 through August, 1969 : * • September, 1966 through August, 1968 : 25 *ACT, Inc. -

A Addison Bay, 64 Advanced Sails, 351

FL07index.qxp 12/7/2007 2:31 PM Page 545 Index A Big Marco Pass, 87 Big Marco River, 64, 84-86 Addison Bay, 64 Big McPherson Bayou, 419, 427 Advanced Sails, 351 Big Sarasota Pass, 265-66, 262 Alafia River, 377-80, 389-90 Bimini Basin, 137, 153-54 Allen Creek, 395-96, 400 Bird Island (off Alafia River), 378-79 Alligator Creek (Punta Gorda), 209-10, Bird Key Yacht Club, 274-75 217 Bishop Harbor, 368 Alligator Point Yacht Basin, 536, 542 Blackburn Bay, 254, 260 American Marina, 494 Blackburn Point Marina, 254 Anclote Harbors Marina, 476, 483 Bleu Provence Restaurant, 78 Anclote Isles Marina, 476-77, 483 Blind Pass Inlet, 420 Anclote Key, 467-69, 471 Blind Pass Marina, 420, 428 Anclote River, 472-84 Boca Bistro Harbor Lights, 192 Anclote Village Marina, 473-74 Boca Ciega Bay, 409-28 Anna Maria Island, 287 Boca Ciega Yacht Club, 412, 423 Anna Maria Sound, 286-88 Boca Grande, 179-90 Apollo Beach, 370-72, 376-77 Boca Grande Bakery, 181 Aripeka, 495-96 Boca Grande Bayou, 188-89, 200 Atsena Otie Key, 514 Boca Grande Lighthouse, 184-85 Boca Grande Lighthouse Museum, 179 Boca Grande Marina, 185-87, 200 B Boca Grande Outfitters, 181 Boca Grande Pass, 178-79, 199-200 Bahia Beach, 369-70, 374-75 Bokeelia Island, 170-71, 197 Barnacle Phil’s Restaurant, 167-68, 196 Bowlees Creek, 278, 297 Barron River, 44-47, 54-55 Boyd Hill Nature Trail, 346 Bay Pines Marina, 430, 440 Braden River, 326 Bayou Grande, 359-60, 365 Bradenton, 317-21, 329-30 Best Western Yacht Harbor Inn, 451 Bradenton Beach Marina, 284, 300 Big Bayou, 345, 362-63 Bradenton Yacht Club, 315-16, -

The Kentucky High School Athlete, August 1970 Kentucky High School Athletic Association

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass The Athlete Kentucky High School Athletic Association 8-1-1970 The Kentucky High School Athlete, August 1970 Kentucky High School Athletic Association Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/athlete Recommended Citation Kentucky High School Athletic Association, "The Kentucky High School Athlete, August 1970" (1970). The Athlete. Book 154. http://encompass.eku.edu/athlete/154 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Kentucky High School Athletic Association at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Athlete by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HiqhSchoolAthMe ELIZABETHTOW'N HIGH SCHOOL BASEBALL TEAM K.H.S.A.A. CHAMPION— 1970 (Left to Right) Front Row: Mgr. R. Bruce, L. Jaggers, S. West, M. Karmon, J. Castle, S. Applegate. Second Row: Stat. C. Knowles, G. Peter- sen, E. Lewis, D. Walters, V. Hartlage, J. Maher, R. Raber. Third Row: Coach R. Myers, R. Thomas, J. Dupin, K. Doyle, K. Clark, D. Sexton, Coach B. Crane. Official Organ of the KENTUCKY HIGH SCHOOL ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION AUGUST, 1970 — — —— — — KENTLTCKY HIGH SCHOOL TRACK MEET—CLASS AAA Louisville, Kentucky, May 22, 1970 Louisville Male High School Track. Team—K.H.S.A.A. Champion 1970 (Left to Right) Front Row: P. Richie, K. Creech, N. Coleman, T. McKane, C. Caffey, R. CampbeU. B. Smith, E. Love, L. Tennyson, E. Hill, M. Johnson, C. Owen, D. Caffey, J. While, Second Row: E. James, D. Brittle, J. McCoUum, R. Butler, D. Murray, C. Duncan, W. Gordon, B. -

Cy Martin Collection

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Cy Martin Collection Martin, Cy (1919–1980). Papers, 1966–1975. 2.33 feet. Author. Manuscripts (1968) of “Your Horoscope,” children’s stories, and books (1973–1975), all written by Martin; magazines (1966–1975), some containing stories by Martin; and biographical information on Cy Martin, who wrote under the pen name of William Stillman Keezer. _________________ Box 1 Real West: May 1966, January 1967, January 1968, April 1968, May 1968, June 1968, May 1969, June 1969, November 1969, May 1972, September 1972, December 1972, February 1973, March 1973, April 1973, June 1973. Real West (annual): 1970, 1972. Frontier West: February 1970, April 1970, June1970. True Frontier: December 1971. Outlaws of the Old West: October 1972. Mental Health and Human Behavior (3rd ed.) by William S. Keezer. The History of Astrology by Zolar. Box 2 Folder: 1. Workbook and experiments in physiological psychology. 2. Workbook for physiological psychology. 3. Cagliostro history. 4. Biographical notes on W.S. Keezer (pen name Cy Martin). 5. Miscellaneous stories (one by Venerable Ancestor Zerkee, others by Grandpa Doc). Real West: December 1969, February 1970, March 1970, May 1970, September 1970, October 1970, November 1970, December 1970, January 1971, May 1971, August 1971, December 1971, January 1972, February 1972. True Frontier: May 1969, September 1970, July 1971. Frontier Times: January 1969. Great West: December 1972. Real Frontier: April 1971. Box 3 Ford Times: February 1968. Popular Medicine: February 1968, December 1968, January 1971. Western Digest: November 1969 (2 copies). Golden West: March 1965, January 1965, May 1965 July 1965, September 1965, January 1966, March 1966, May 1966, September 1970, September 1970 (partial), July 1972, August 1972, November 1972, December 1972, December 1973. -

Taxation Section: Michigan Tax Lawyer December 1970

l~)" .~.~~x.; tiTf1J.-L UNIVERSITY fEB~~ 1971 PUBLISHED BY THE STATE BAR OF MICHIGAN FOR DISTRIBUTION TO MEMBERS OF THE TAXATION SECTION DECEMBER, 1970 ISSUE TAXATION SECTION COUNCIL and LIAISON MEMBERS Basil M. Briggs TAX E. James Gamble DOINGS James E. Beall Peter Van Domelen Ill J. Bruce Donaldson Joseph D. Hartwig EDITOR .......... I. John Snider II Miles Jaffe Maurice B. Townsend, Jr. statements, opinions and comments appearing herein are those of the I. John Snider II editors or contributors and not neces sarily .those of the Association or OFFICERS Section. Chairman Clifford H. Domke Vice-Chairman Calvert Thomas Secretary-Treasurer Benjamin 0. Schwendener, Jr. IN THIS ISSUE ~ r 1- Statement of Editor. II- Minutes of Meeting Between Internal Revenue Service Offi cials and Bar Association Liaison Group for the Central Region, Internal Revenue Service, held November 18, 1970 at Cincinnati, Ohio. 1 STATEMENT OF THE EDITOR This first edition of the 1970-1971 "Tax Doings," contains the major portion of the minutes of the meeting of the Internal Revenue Service officials and the Bar Association Liaison Group. As noted in the text, some portions have been excised because of the length of the text and will be appearing in the next edition. Most of the tax practitioners agree that the material which ap pears in these minutes is of real value in working with the Internal 1 Revenue Service. In order for this relationship of the Internal Revenue Service officials and the Bar Association Liaison Group to be mean ingful, the Bar must be willing to raise any problems with the officials. -

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Division of Law

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Division of Law Enforcement Weekly Report Patrol, Protect, Preserve August 16, 2019 through August 29, 2019 This report represents some events the FWC handled over the past two weeks; however, it does not include all actions taken by the Division of Law Enforcement. NORTHWEST REGION CASES BAY COUNTY Officer T. Basford was working the area known as North Shore when he noticed a couple of vehicles parked on the shoulder of the road. He later saw two individuals coming towards the vehicles with fishing gear. Officer Basford conducted a resource inspection and found the two men to be in possession of two redfish. One individual admitted to catching both fish. He was issued a citation for possession of over daily bag limit of redfish. GADSDEN COUNTY Lieutenant Holcomb passed a truck with a single passenger sitting on the side of the road with the window down. He conducted a welfare check and found the individual in possession of a loaded 30-30 rifle and an empty corn bag in the cab of the truck. Further investigation led to locating corn scattered along the roadway shoulders adjacent to the individual’s truck. The individual admitted to placing the corn along the roadway and was cited accordingly. GULF COUNTY Officers T. Basford and Wicker observed a vessel in the Gulf County Canal near the Highland View Bridge and conducted a resource inspection. During the inspection Officer Basford located several fish fillets which were determined to be redfish, sheepshead and black drum. The captain of the vessel was issued citations for the violation of fish not being landed in whole condition. -

009 OTP Materials July 1970-December 1970

Wednesday 12/9/70 4:00 Dr. Lyons called to tell you that he has seen nothing in the papers about it, but the Congressional Record indicates that the appropriations bill passed the Senate on Monday — 75 to 1. It was the Independent Office HUD appropriations bill that the President vetoed once. 8 DEC 1970 Mr. Eric Hager, Esq. Shearman and Sterling 531 Wall Street New York, New York 10005 Dear Eric: As promised, I report with some cheer that I have hired a general counsel. He is outstanding on all my criteria except for a lack of Washington experience, and I figured there that I might as well have him learn along with me. We are moving along in our preparations for the World Administrative Radio Conference in Geneva next June, at least insofar as preparation of the U.S. formal position is concerned, which must be submitted in January. 1 am also beginning to seek out an outstanding technical type from outside government who could serve as a vice chairman of the delegation representing OT?. I would like to pursue the question of your availability with you at more length as 110011 as you feel able to do so. I think that it is fair to state that at this point both State and OTP feel you would be an outstanding choice. I personally hope you can see you way clear and loot forward to hearing from you. Sincerely, Clay T. Whitehead .0 'A it Jr EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT OFFICE OF TELECOMMUNICATIONS POLICY WASHINGTON, D.C. -

Download NOVEMBER 1970.Pdf

NOVEMBER 1970 - LAW ENFORCEMENT BULLETIN THANKSGIVING PROCLAMATION City of New York October 3, 1789. " and Whereas both Houses of Congress have by their joint Committee requested me 'to recommend to the People of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many signalfavors of Almighty God, . .' Now therefore I do recommend and assign Thursday the 26th. day of November next to be devoted by the People of these States to the service of that great and glorious Being, who is the beneficent Author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be. ." GEORGE WASHINGTON By the President FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE J. EDGAR HOOVER, DIRECTOR NOVEMBER 1970 VOL. 39, NO. 11 _.- --_.. THE COVER-The first Thanksgiving proclama· tion. See Director Hoo· ver' s Message, page 1. LAW ENFORCEMENT BULLETIN CONTENTS Message From Director]' Edgar Hoover 1 Twenty-Four Hour Patrol Power, by Winston L. Churchill, Chief of Police, Indianapolis, Ind. 2 What Is a Policeman? . 6 Drug Abuse Councils, by Dr. Heber H. Cleveland, President, State Drug Abuse Council, Augusta, Maine. 9 The Supervisor and Morale. 13 Have You Considered a Teenage Cadet Program?, by Raynor Weizenecker, Sheriff of Putnam County, Carmel, N.Y. 16 Nationwide Crimescope . 20 Published by the The "Loan" Bank Robber 21 FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION Investigators' A ids 30 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE Washington, D.C. 20535 Wanted by the FBI 32 4 MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR • • • . To All Law Enforcement Officials THE SPIRIT OF THANKSGIVING encompasses have spent weary lives in unrewarded toil, in many principles and ideals which deserve daily anxiety, in helplessness, in ignorance, have risen as well as annual tribute. -

Notes on the Birds of Southampton Island, Northwest Territories

Notes on the Birds of Southampton Island, Northwest Territories GERALD R. PARKER'and R. KENYONROSS2 ABSTRACT. During thesummers of 1970 and 1971,46 species were seenon Southamp- ton Island, most in the interior of the island where previous records were scarce. A comparison with observations in 1932 suggestslittle change in thestatus of the avifauna of the island over the past 40 years. RÉSUMÉ: Notes sur les oiseaux deI'île de Southampton, Territoires du Nord-Ouest. Au cours des étés de 1970 et 1911, les auteurs ont aperçu sur l'île de Southampton 46 esphces, la plupart dans l'intérieur, où les mentions antérieures sont rares. La comparaison avec des observations de 1932 montre peu de changement dans l'état de l'avifaune de l'île au cours des'40 dernièresannées. PE3HI". ET eonpocy O nmuym ocmposa CagrnZemwnoH Cesepo-9anadnw Tep- PUmOpUU). B TeYeHHe JIeTHHX nepHonoB 1970 H 197lrr Ha OCTpOBe CayTreMIITOH 6~noSaMerfeHO 46 BIlnOB IlTIl4, FJIaBHbIM 06pa30~,BO BHYTPeHHefi YaCTH OCTPOBB, rge paHee perzwrpaqm EIX npoBoAHnacb peAIco. CpaBHeme c H~~JII~A~HEI~EI 1932rnoIcasmBaeT, YTO nTmbrx 4ayHa ocTposa Mano H~M~HEI~~CLsa nocnenme 40 neT. INTRODUCTION A barren-ground caribourange evaluation of Southampton Island, conducted by the Canadian Wildlife Service, provided the opportunity to observe the birds on the island during the periods 2 June to 14 August 1970 and 1 July to 31 August 1971. The main camp in 1970 was on the Southampton Limestone Plains of the Hudson Bay Lowlands (Bird 1953) at Salmon Pond (64" 14' N., 85" 00' W.), although several trips were made in July, 15 miles northeast to the Precambrian highlands. -

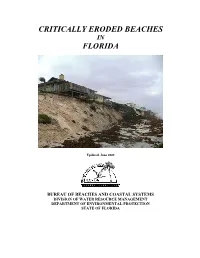

Currently the Bureau of Beaches and Coastal Systems

CRITICALLY ERODED BEACHES IN FLORIDA Updated, June 2009 BUREAU OF BEACHES AND COASTAL SYSTEMS DIVISION OF WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION STATE OF FLORIDA Foreword This report provides an inventory of Florida's erosion problem areas fronting on the Atlantic Ocean, Straits of Florida, Gulf of Mexico, and the roughly seventy coastal barrier tidal inlets. The erosion problem areas are classified as either critical or noncritical and county maps and tables are provided to depict the areas designated critically and noncritically eroded. This report is periodically updated to include additions and deletions. A county index is provided on page 13, which includes the date of the last revision. All information is provided for planning purposes only and the user is cautioned to obtain the most recent erosion areas listing available. This report is also available on the following web site: http://www.dep.state.fl.us/beaches/uublications/tech-rut.htm APPROVED BY Michael R. Barnett, P.E., Bureau Chief Bureau of Beaches and Coastal Systems June, 2009 Introduction In 1986, pursuant to Sections 161.101 and 161.161, Florida Statutes, the Department of Natural Resources, Division of Beaches and Shores (now the Department of Environmental Protection, Bureau of Beaches and Coastal Systems) was charged with the responsibility to identify those beaches of the state which are critically eroding and to develop and maintain a comprehensive long-term management plan for their restoration. In 1989, a first list of erosion areas was developed based upon an abbreviated definition of critical erosion. That list included 217.6 miles of critical erosion and another 114.8 miles of noncritical erosion statewide. -

International Review of the Red Cross, November 1970, Tenth Year

JAN 1 4 I9n NOVEMBER 1970 TENTH YEAR - No. 116 PROPERTY OF U. S. ARMY THE JUDGE ADVOCATE GENERAL'S SCHOOL UBRARY international review• of the red cross . • INTER+ ARMA CARITAS GENEVA INTERNATIONAL COMMITIEE OF THE REO CROSS FOUNDED IN 1863 INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS MARCEL A. NAVILLE, P,esident (member since 1967) HANS BACHMANN, Doctor of Laws, Winterthur Stadtrat, Vice-P,esident (1958) JACQUES FREYMOND, Doctor of Literature, Director of the Graduate Institute of International Studies, Professor at the University of Geneva, Vice-P1'esident (1959) MARTIN BODMER, Hon. Doctor of Philosophy (1940) PAUL RUEGGER, Ambassador, President of the ICRC from 1948 to 1955 (1948) RODOLFO OLGIATI, Hon. Doctor of Medicine, Director of the Don Suisse from 1944 to 1948 (1949) GUILLAUME BORDIER, Certificated Engineer E.P.F., M.B.A. Harvard, Banker (1955) DIETRICH SCHINDLER, Doctor of Laws, Professor at the University of Zurich (l96t) HANS MEULI, Doctor of Medicine, Brigade Colonel, Director of the Swiss Army Medical Service from 1946 to 1960 (1961) MARJORIE DUVILLARD, nurse (1961) MAX PETITPIERRE, Doctor of Laws, former President of the Swiss Confederation (1961) ADOLPHE GRAEDEL, member of the Swiss National Council from 1951 to 1963, former Secretary-General of the International Metal Workers Federation (1965) DENISE BINDSCHEDLER-ROBERT, Doctor of Laws, Professor at the Graduate Institute of International Studies (1967) JACQUES F. DE ROUGEMONT, Doctor of Medicine (1967) ROGER GALLOPIN, Doctor of Laws, fonner Director-General (1967) JEAN PICTET, Doctor of Laws, Chainnan of the Legal Commission (1967) WALDEMAR JUCKER, Doctor of Laws, Secretary, Union syndicale suisse (1967) HARALD HUBER, Doctor of Laws, Federal Court Judge (1969) VICTOR H.