Athabasca University University of Calgary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-LPN BN Professional Practice (Clinical) Preparation Guide

Post-LPN BN Professional Practice (Clinical) Preparation Guide Post-LPN BN students registering in professional practice (clinical) courses must be prepared to demonstrate, at a minimum, the knowledge, skills, and clinical behaviours outlined in the College of Licensed Practical Nurses of Alberta, Competency Profile for LPN’s, 5th edition, February, 2020 Students are required to seek self-remediation as needed prior to registration in NURS 401, NURS 435, and NURS 437. Throughout the clinical courses, students (with guidance from instructors/preceptors) will be expected to progress toward meeting College and Association of Registered Nurses of Alberta, Entry-Level Competencies for the Practice of Registered Nurses (March 2019) Read this entire document prior to planning to register in clinical courses to understand all requirements. Note: A program GPA of 3.0 is required for all clinical courses. Students are responsible for: • meeting all deadlines • completing pre-requisite courses • earning a program GPA of 3.0 • submitting pre-requisite clinical placement documentation • reviewing Alberta Health Services (AHS) and other clinical placement agency modules; and • registering in clinical courses prior to deadlines. Clinical Courses Clinical courses are offered three times per year and are “paced” over a four-month period. A paced course means that students work together with set timelines and due dates to complete the course. One clinical course can be taken per term. • Fall term: September–December • Winter term: January–April • Spring term: April-July for NURS 401; May–August for NURS 435, 437, 441 NURS 401: Professional Practice with Adults Experiencing Health Alterations • An invigilated Medication Safety and Calculation Quiz must be successfully completed in the first month of the course, prior to the four-week clinical rotation. -

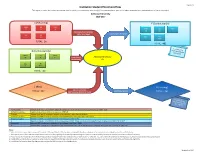

Institution Student Enrolment Flow

Page 1 of 2 Institution Student Enrolment Flow This report provides the student enrolment data for public post-secondary institution(s) for a given academic year and student movement into, within and out of the institution(s). Ambrose University 2017-2018 A (Returning) E (Continuing On) CARU UU POLY 7 6 4 CARU UU POLY 70 8 5 From System to Institution (After Year Away) Continuing in the System CCC IAI 4 16 CCC IAI 10 424 TOTAL:Alberta 30University of the Arts TOTAL: 472 B (Continuing Into) CARU UU POLY 35 5 7 From System Ambrose University to Institution 701 CCC IAI 5 431 TOTAL: 458 C (New) G (Leaving) New to Institution Leaving the System TOTAL: 213 (Not in System for Prev. 6 Years) TOTAL: 229 A (Returning) Students that were not enrolled in 2016-17, but had an enrolment record at some point between 2011 - 2016 B (Continuing into) Students that were enrolled in the system in 2016-17 C (New) Students that had NO enrolment records in the previous 6 years (New to system) D (Student Cohort) Students enrolled full-time or part-time in the institution(s) in the cohort year (2017-2018) E (Continuing On) Students enrolled in an institution for the following year (2018-2019) F Students enrolled in an institution for the following year (2018-2019), and received a credential from Ambrose University in 2017-2018 G (Leaving) Students NOT enrolled at an institution in the following year (2018-2019) H Students NOT enrolled in an institution for the following year (2018-2019), but received a credential from Ambrose University in 2017-2018 Notes: 1. -

7. Undergraduate Fees and Refunds

Undergraduate 7. Undergraduate Fees Calendar Home and Refunds General Information The following fees are effective for students registering with a start date of Student September 1, 2018 to August 31, 2019. Support Services Course fees are all-inclusive, and are calculated by combining the tuition fees, Admission, learning resources fee, and Students’ Registration Union and Alumni Relations fees. and Evaluation If you formally withdraw from your individualized study course or your Undergraduate grouped study course, you must follow the Programs regulations in the following sections that apply to you. Undergraduate Courses For more information related to undergraduate fees and refunds, use the Examinations links on the left. and Grades Undergraduate Fees and Information effective Sept. 1, 2018 to Refunds Aug. 31, 2019. Fees Updated June 18 2018 by laurab Refunds Delinquent Accounts Receipts Form T2202A The content on these pages was captured on January 11, 2019, and is effective January 1, 2019 to August 31, 2019. The online Calendar is the official version. If there are any discrepancies between this publication and the online version, the online Calendar will be binding. Undergraduate Undergraduate Fees and Calendar Home Refunds General Information 7.1 Fees Student Support The following fees are effective for Services students registering with a start date of September 1, 2018 to August 31, 2019. Admission, Registration Course fees are all-inclusive and are calculated by combining the tuition fees, and Evaluation learning resources fee, and Students' Undergraduate Union and Alumni Relations fees. Choose the fees relevant to your situation from Programs the links on the left. Undergraduate Courses Information effective Sept. -

Institution Student Enrolment Flow

Page 1 of 2 Institution Student Enrolment Flow This report provides the student enrolment data for public post-secondary institution(s) for a given academic year and student movement into, within and out of the institution(s). Ambrose University 2016-2017 A (Returning) E (Continuing On) CARU UU POLY 12 9 9 CARU UU POLY 73 12 6 From System to Institution (After Year Away) Continuing in the System CCC IAI 4 16 CCC IAI 7 428 TOTAL: 36 TOTAL: 482 B (Continuing Into) CARU UU POLY 43 8 5 From System Ambrose University to Institution 725 CCC IAI 4 431 TOTAL: 457 C (New) G (Leaving) New to Institution Leaving the System TOTAL: 232 (Not in System for Prev. 6 Years) TOTAL: 243 A (Returning) Students that were not enrolled in 2015-16, but had an enrolment record at some point between 2010 - 2015 B (Continuing into) Students that were enrolled in the system in 2015-16 C (New) Students that had NO enrolment records in the previous 6 years (New to system) D (Student Cohort) Students enrolled full-time or part-time in the institution(s) in the cohort year (2016-2017) E (Continuing On) Students enrolled in an institution for the following year (2017-2018) F Students enrolled in an institution for the following year (2017-2018), and received a credential from Ambrose University in 2016-2017 G (Leaving) Students NOT enrolled at an institution in the following year (2017-2018) H Students NOT enrolled in an institution for the following year (2017-2018), but received a credential from Ambrose University in 2016-2017 Notes: 1. -

Introduction

University of Lethbridge STUDENT FEE REPORT – 2004-05 Introduction • Instructional fees are only one of several financial components that determine the cost of education at the University of Lethbridge. In addition to tuition and other mandatory fees, related costs including textbooks, parking, housing and food must be considered. This report compares the changing costs of education over a ten-year period from 1994-95 to 2004-05 at the University of Lethbridge. These costs are then compared to other Western Canadian Universities for the same years. With increasing operating costs and low provincial grants, it is important to maintain current levels of enrolment. Maintaining competitive fees is one way to achieve this. • The University Calendar, Proposed Fees and Rates report, and the Student Debt report provided in depth information on all fees charged to students at the University of Lethbridge. This report gives the amount of a fee, explains the fee’s purpose, and compares the fee to those charged at other Western Canadian Universities. University of Lethbridge STUDENT FEE REPORT – 2004-05 Table of Contents Executive Summary Pg Glossary of Fees Pg Fee Descriptions Pg Analysis Table 1: Student Budget Analysis Table Pg Student Budget Analysis Pg Graph 1: Sample Student Budgets Pg Table 2: Fee Comparison 1994-2005 Pg University Revenue Analysis Pg Table 3: Tuition Revenue Pg Graph 2: % Difference Revenue Analysis Pg Graph 3: U of L Tuition Fees (1993/94-2003/04) Pg Table 4: Revenues Pg Graph 4: Revenue Distribution (%) Pg Graph 5: Revenue Distribution ($) Pg Table 5: Revenue Analysis Pg Graph 6: % Changes in Enrolment, etc. -

2015–2016 Academic Calendar Macewan University

2015–2016 Academic Calendar MacEwan University MacEwan University • 2015–2016 A C A D E M I C C A L E N D A R • MacEwan.ca 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION APPLIED DEGREE PROGRAMS 4 2015–2016 Academic Schedule 95 Bachelor of Applied Business Administration – 5 2015–2016 Holidays Observed Accounting 6 University Pillars 97 Bachelor of Applied Communications in Professional 6 Positioning Statement Writing – suspended 6 Educational Philosophy Statement 98 Bachelor of Applied Human Service Administration 6 Educational Goals POST-DIPLOMA CERTIFICATE PROGRAMS 7 Campus Locations 101 Cardiac Nursing Post-basic Certificate 8 Phone Directory 102 Perioperative Nursing for Registered Nurses REGISTRARIAL INFORMATION 104 Post-basic Nursing Practice 11 Admissions and Transfer 106 Wound Management Post-basic Certificate 20 Enrolment UNIVERSITY TRANSFER PROGRAMS 21 Student Records and Transcripts 109 Bachelor of Physical Education Transfer 24 Fees 111 Bachelor of Science in Engineering Transfer 29 Educational Funding, Scholarships and Awards 30 International Students CERTIFICATE AND DIPLOMA PROGRAMS 32 Institutional Graduation Regulations 114 Accounting and Strategic Measurement 32 Policies 117 Acupuncture 120 Arts and Cultural Management SERVICES FOR STUDENTS 123 Asia Pacific Management 34 Aboriginal Education Centre 125 Business Management 34 Alumni Status 131 Correctional Services 34 Child Care Centre 133 Design Studies 34 Library 137 Design Studies (3 majors)– suspended 34 MacEwan Athletics 140 Disability Management in the Workplace 34 MacEwan Bookstores 142 -

Athabasca University

ATHABASCA UNIVERSITY A CASE STUDY IN OPEN EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES PRODUCTION AND USE IN HIGHER EDUCATION IN CANADA May 2006 PREPARED FOR THE CANADIAN COUNCIL ON LEARNING BY WALTER STEWART & ASSOCIATES www.walterstewartassociates.com WALTER STEWART, PRESIDENT 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND .................................................................................... 3 WHY ATHABASCA WAS CHOSEN........................................................ 5 STATE OF THE ART ............................................................................. 6 OPEN CONTENT PRODUCTION .................................................................. 6 OPEN CONTENT USE .............................................................................. 7 OPEN SOURCE SOFTWARE PRODUCTION..................................................... 8 Open Source Software Use .............................................................. 9 CONCLUSION ................................................................................... 10 APPENDICES .................................................................................... 11 LIST OF INTERVIEWEES........................................................................ 11 USEFUL LINKS ................................................................................... 11 2 1.00 GENERAL BACKGROUND 1. The origins of Athabasca University lie in the 1960s' rapid increase in university enrolments, which argued strongly for a fourth Alberta university. In response to these pressures, Athabasca University was created -

Grant Macewan University Celebrates New Name

September 24, 2009 Grant MacEwan University celebrates new name Edmonton... Students from across the province can now attend Grant MacEwan University, as the institution has been formally renamed by the Alberta government. “The needs of Alberta students are changing and our world-class post-secondary institutions are ahead of the curve in terms of providing the best educational opportunities anywhere,” said Premier Ed Stelmach. “Grant MacEwan University is an outstanding institution that has shown there is an exciting alternative for undergraduate studies.” “Dr. MacEwan was famous for saying, ‘leave the garden better than you found it’ and I believe that by renaming the institution a university we are enhancing and confirming the influential role that Grant MacEwan University has on Campus Alberta, the province and on generations of Albertans,” added Stelmach. Grant MacEwan University’s mandate will continue as a Baccalaureate and Applied Studies Institution under Campus Alberta’s six-sector post-secondary model. The institution provides a broad array of programs, including certificates, diplomas, applied degrees, and baccalaureate degrees. “Grant MacEwan University’s commitment to affordable, accessible and quality education mirrors the goals of Campus Alberta, which is to provide the right programs to learners where and when they need them,” said Doug Horner, Minister of Advanced Education and Technology. “Over the past few years, it has been offering high calibre and innovative bachelor degrees, as part of the educational choices available, in an intimate and comfortable learning environment.” Using the term ‘university’ recognizes the high level of baccalaureate degree programs that students receive at Grant MacEwan University. Students will have better opportunities to transition to higher learning in graduate programming and into the workforce. -

CSR Case Study: Syncrude Canada Ltd. Earning Its Social License to Operate

CSR Case Study: Syncrude Canada Ltd. Earning its Social License to Operate FINAL Prepared for: Interdepartmental Working Group on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Corporate Social Responsibility: Lessons Learned Final Syncrude Case Study 1 Corporate Overview Syncrude Canada Ltd is the world’s largest producer of crude oil from oil sands. In 2001, the company produced 81.4 million barrels of sweet crude oil—the equivalent of 223 000 barrels a day—and supplied Canada with 13 percent of its petroleum needs. Syncrude’s final refined product, Syncrude Sweet Blend, is sent south by pipeline to refineries in Edmonton, the USA and the rest of Canada, where it is further refined into gasoline, diesel fuel and other derivatives. The company’s revenues in 2001 were $3.2 billion. Syncrude’s operations are located on the Athabasca oil sands deposit near the First Nations community of Fort McKay in the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo of north-eastern Alberta. In 1983, Syncrude moved its headquarters from Edmonton to Fort McMurray, 435 kilometres to the north, in order to be closer to its operations. Fort McMurray is a one-industry town of 50 000 people, that until recently had only two players: Syncrude and Suncor. This has begun to change as new companies have entered the oil sands business. Large new comers include Shell/Albian, EnCana Corporation, Canadian Natural Resources, Petro-Canada, True North Energy, and Nexen, among others. Despite this, Syncrude remains a large presence situated in one of the most sparsely populated regions in Canada. Syncrude was established in 1964 as a joint venture whose initial objective was to investigate the feasibility of mining oil from the Athabasca oil sands. -

List of Member Institutions

List of Member Institutions Angelo State University Anoka-Ramsey Community College Athabasca University Ball State University Baptist Memorial College of Health Sciences Bentley University Berea College Blue Ridge Community and Technical College Boise State University Bowie State University Brandeis University California Institute of Technology California Polytechnic State University California State University, Chico California State University, Fullerton California State University, San Bernardino California State University-San Marcos Cape Breton University Carleton University Carnegie Mellon University Case Western Reserve University Centennial College Chattanooga State Community College Claremont School of Theology Clarkson University Colby College College of Our Lady of the Elms College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University College of the Holy Cross Academic Impressions 720.488.6800 facebook.com/academicimpressions www.academicimpressions.com twitter.com/academicimpress Colorado College Colorado State University-Pueblo Columbia Basin College Confederation College Coppin State University CUNY System Office DeSales University Diné College Drexel University Earlham College Fairleigh Dickinson University Fitchburg State University Flagler College Florida Polytechnic University Georgetown University Georgia Gwinnett College Georgian College Georgia Southern University Georgia State University Grinnell College Hamline University Havergal College Helena College University of Montana Hofstra University Humboldt State University Husson -

Syncrude Sustainability Report 2017-18

SYNCRUDE SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2017-18 ABOUT THIS REPORT This report is a highlights summary of the environmental, social and economic impacts of Syncrude’s operations during 2017. More information about the topics in this book can be found online at www.syncrude.ca. Based in Fort McMurray, Alberta, Syncrude operates technologically-advanced oil sands mines, extraction and upgrading facilities, as well as Syncrude is utilities plants. A large research and development facility in Edmonton one of the largest supports operations and has pioneered many of the technologies used today operators in in the industry. Current production capacity is 350,000 barrels per day Canada’s oil sands of high quality light sweet crude oil and cumulative shipments now industry, with over exceed 2.6 billion barrels. 50 years of responsible operations and ongoing innovation. Indigenous plant species are grown for use in reclamation programs in areas that were previously mined. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Leader’s Letter 3 2017 Highlights Wetlands are a key component of our ongoing 5 Our Sustainability reclamation strategy. Approach Pictured here, the reclaimed Sandhill Fen 6 2017 Corporate wetland research area. Performance Summary 9 Environmental Sustainability 10 Land 13 Biodiversity 18 Tailings 20 Water 23 Climate Change 26 Air 29 Social Sustainability 30 Health & Safety 33 Aboriginal Relations 36 Community Relations 39 People 43 Economic Sustainability 44 Operations & Economic Value 50 Key Performance Indicators BC Contact Information 2HECTARES15 OF FORMER MINE AREAS RECLAIMED IN 2017 1 LEADER’S LETTER People are the heart and soul of any organization. And at Syncrude, the determination, resolve and mindfulness of our people is forging the path to a truly sustainable company. -

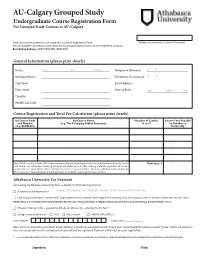

AU-Calgary Grouped Study Undergraduate Course Registration Form for Grouped Study Courses at AU-Calgary

AU-Calgary Grouped Study Undergraduate Course Registration Form For Grouped Study Courses at AU-Calgary New and inactive students must complete a General Application Form. Athabasca University Student ID Number Please complete all sections of this form for AU grouped study courses to be completed onsite at Bow Valley College. (ONE FORM PER SEMESTER) General Information (please print clearly) Name: ______________LAST ______________________________ FIRST MIDDLE Telephone (Primary): ___________________________( ) Mailing Address: ____________________________________________ Telephone (Secondary): ___________________________( ) City/Town: ____________________________________________ Email Address: ___________________________ Prov./State: ____________________________________________ Date of Birth: ___________________________ DAY MONTH YEAR Country: ____________________________________________ Postal/ Zip Code: ____________________________________________ Course Registration and Total Fee Calculation (please print clearly) AU Course Code AU Course Name Number of Credits Course Fees Payable and Number (e.g. The Changing Global Economy) (3 or 6) to Athabasca (e.g. ECON 401) University Note: The Course Fee includes AU's fully integrated tuition and learning resources fee, and mandatory students' union Total fees: ‡ and alumni association fees. Learning resources are textbooks and other learning materials, regardless of format, outlined in the course syllabus. The learning resources fee is non-refundable unless you withdraw within 30 days of the course start date and return all learning resources to AU unopened and in new condition. Athabasca University Fee Payment I am paying my Athabasca University fees as detailed in the following manner: c A sponsor is paying my fees: ______________________________________________________________________________ PROVIDE SPONSOR NAME AND ATTACH THE SPONSOR'S LETTER OF GUARANTEE TO THIS FORM. c I am using Government Student Aid* (loans/grants) and I confirm I have applied for funding.