Morality, Justice, and Freedom in World War II Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jennifer Ricchiazzi, Csa

JENNIFER RICCHIAZZI, CSA www.jenniferricchiazzi.com Selected Film & Television Credits FUTRA DAYS (Pre-Production/Currently Casting) Producer: Ryan David, Orian Williams, David Zonshine. Director/Writer: Ryan David. SHOOTING HEROIN (Post-Production) Producer: Mark Joseph. Director/Writer: Spencer Folmar. Starring: Alan Powell, Cathy Moriarty, Sherilyn Fenn, Nicholas Turturro THE UNSPOKEN (Pre-Production) Winterland Pictures. Producers: Lionel Hicks, Rebecca Tranter. Director/Writer: Andrew Hunt FIGHTING CHANCE (Pre-Production) Producers: Scott Rosenfelt, Ron Winston. Director: Mikael Salomon FALL OF EDEN (Pre-Production) Producer: Mark G Mathis. Director: Susan Dynner. Attached: Dylan McDermott, Brianna Hildebrand. BLINDED BY ED (Pre-Production) Producer: Kristy Lash. Director/Writer: Chris Fetchko. Attached: Katrina Bowden. REAGAN (Pre-Production) Independent. Producer: Mark Joseph; Executive Producer: Dawn Krantz. Director: John G. Avildsen. Attached: Jon Voight and Dennis Quaid. HAUNTING OF THE MARY CELESTE Vertical Entertainment. Producers: Norman Dreyfuss, Brian Dreyfuss, Justin Ambrosino. Writer: David Ross; Executive Producers: Eric Brodeur, Jerome Oliver. Director: Shana Betz. Starring: Emily Swallow. SOLVE Mobile Series. Vertical Networks; Snapchat. THE STOLEN Independent/Cork Films Ltd. Producer/Writer: Emily Corcoran; Executive Producer: Julia Palau. Director/Co-Writer: Niall Johnson. Starring: Alice Eve, Jack Davenport. THE CLAPPER (Tribeca Film Festival 2017) Independent. Producer: Robin Schorr. Director: Dito Montiel. Starring: -

7.Castrillo-Echart

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Dadun, University of Navarra Pablo Castrillo Towards a narrative definition of [email protected] PhD Candidate and Lecturer. the American political thriller film University of Navarra. Spain. Pablo Echart Abstract [email protected] Senior Lecturer in The Hollywood political thriller is a film genre of unique Screenwriting. University of relevance in the United States, often acting as a reflection of the Navarra. Spain. fears and anxieties of its historical times. At the same time, however, the definition of its identity and boundaries still leaves Submitted room for further specification, perhaps due to the frequent June 4, 2015 consideration of the political thriller as part of the broader Approved September 30, 2015 categories of either thriller narratives or political films. By revising the available literature and filmography and analyzing the narrative features of the classical political thriller, this © 2015 Communication & Society article proposes a deeper definition of the genre that takes into ISSN 0214-0039 account the nature of the broader ‘thriller’ category of films E ISSN 2386-7876 springing from a specific mode of crime fiction that focuses on a doi: 10.15581/003.28.4. 109-123 www.communication-society.com victim or threatened individual as its protagonist, depicts and conveys intense emotional states, portrays an unbalanced and highly existentialist worldview, and travels into the 2015 – Vol. 28(4), pp. 109-123 extraordinary while at the same time holding on to very concrete expectations of verisimilitude. The political thriller How to cite this article: specifies this broader form of narration and links it to dramatic Castrillo, P. -

Locations of Motherhood in Shakespeare on Film

Volume 2 (2), 2009 ISSN 1756-8226 Locations of Motherhood in Shakespeare on Film LAURA GALLAGHER Queens University Belfast Adelman’s Suffocating Mothers (1992) appropriates feminist psychoanalysis to illustrate how the suppression of the female is represented in selected Shakespearean play-texts (chronologically from Hamlet to The Tempest ) in the attempted expulsion of the mother in order to recover the masculine sense of identity. She argues that Hamlet operates as a watershed in Shakespeare’s canon, marking the prominent return of the problematic maternal presence: “selfhood grounded in paternal absence and in the fantasy of overwhelming contamination at the site of origin – becomes the tragic burden of Hamlet and the men who come after him” (1992, p.10). The maternal body is thus constructed as the site of contamination, of simultaneous attraction and disgust, of fantasies that she cannot hold: she is the slippage between boundaries – the abject. Julia Kristeva’s theory of the abject (1982) ostensibly provides a hypothesis for analysis of women in the horror film, yet the theory also provides a critical means of situating the maternal figure, the “monstrous- feminine” in film versions of Shakespeare (Creed, 1993, 1996). Therefore the choice to focus on the selected Hamlet , Macbeth , Titus Andronicus and Richard III film versions reflects the centrality of the mother figure in these play-texts, and the chosen adaptations most powerfully illuminate this article’s thesis. Crucially, in contrast to Adelman’s identification of the attempted suppression of the “suffocating mother” figures 1, in adapting the text to film the absent maternal figure is forced into (an extended) presence on screen. -

The Appropriateness of William Shakespeare's

T.C. SELÇUK ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ İNGİLİZ DİLİ VE EDEBİYATI ANA BİLİM DALI İNGİLİZ DİLİ VE EDEBİYATI BİLİM DALI THE APPROPRIATENESS OF WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE'S RICHARD III TO FILM ADAPTATION YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ DANIŞMAN YRD. DOÇ. DR. GÜLBÜN ONUR HAZİRLAYAN ŞEFİKA BİLGE CANTEKİNLER KONYA, 2005 ÖZET 1930ların başında Hollywood ile birlikte yükselen Amerikan Film Endüstrisi vazgeçilmez kaynakları arasında ünlü İngiliz oyun yazarı William Shakespeare'in eserlerini ilk sıraya oturtmuştur. Sessiz sinemadan günümüz üç boyutlu animasyon film dönemine geçişte klasik Shakespeare oyunları da her yeni yönetmen ve yapımcıyla birlikte farklı bir boyut kazanmıştır. Tarihsel bir trajedi olan Shakespeare'in III. Richard adlı oyunu ilk oynandığı 1590lardan günümüze kadar geçen sürede en çok sahnelenen ama en az anlaşılan oyunlardan biri olmuştur. Buna bağlı olarak III. Richard'ın seçilen üç film uyarlaması oyunu farkh yonlerden ele almışlardır. İlk film İngiliz aktör- yönetmen Sir Laurence Oliver'in 1955 film uyarlaması III. Richard, ikincisi İngiliz yönetmen Richard Loncraine'in İngiliz aktör-yönetmen Ian McKellen ile birlikte çektiği 1995 yapımı III. Richard ve sonuncusu da Amerikalı aktör Al Pacino'nun yönetip başrol oynadığı Looking For Richard (Richard'ı Aramak) adlı filmidir. Bu çalışma, seçilen üç sahne ile oyunun kahramanı olan III. Richard'ın yükseliş ve çöküşünü temel alarak üç film uyarlaması arasındaki farklılıkları değerlendirmektedir. Ayrıca, a9ihs monoloğu, kur yapma, baştan çıkarma ile savaş sahneleri incelenerek bunların Shakespeare'in metnini ne derece yansıttıkları ve bu sahnelerin birbirinden nasıl farklı olarak ele alındığını belirtmektedir. ABSTRACT Within the rise of Hollywood productions at the beginning of the 1930s, American Film Industry put the works of famous British playwright William Shakespeare at its one of the most indispensable sources. -

TREFOR PROUD Make-Up Artist IATSE 706 Journeyman Member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

TREFOR PROUD Make-Up Artist IATSE 706 Journeyman Member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences FILM MR. CHURCH Make-Up Department Head Director: Bruce Beresford Cast: Britt Robertson, Xavier Samuel, Christian Madsen SPY Make-Up Department Head Director: Paul Feig Cast: Jason Statham, Rose Byrme, Peter Serafinowicz, Julian Miller THE PURGE 2 - ANARCHY Make-Up Department Head and Mask Design Director: James DeMonaco Cast: Michael K. Williams, Frank Grillo, Carmen Ejogo BONNIE AND CLYDE Make-Up Department Head Director: Bruce Beresford Cast: Emile Hirsch, Holly Hunter, William Hurt, Sarah Hyland Nominee: Emmy – Outstanding Make-Up for a Miniseries or a Movie (Non-Prosthetic) ENDER’S GAME Make-Up Department Head Director: Gavin Hood Cast: Harrison Ford, Asa Butterfield, Sir Ben Kingsley JACK REACHER Make-Up Department Head Director: Christopher McQuarrie Cast: Rosamund Pike, Robert Duvall THE RITE Make-Up and Hair Designer Director: Mikael Håfström Cast: Alice Braga, Anthony Hopkins, Ciarán Hinds A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET Department Head Make-Up, Los Angeles Director: Samuel Bayer Cast: Jackie Earle Hayley, Kyle Gallner, Rooney Mara, Katie Cassidy, Thomas Dekker, Kellan Lutz, Clancy Brown LONDON DREAMS Make-Up and Hair Designer Director: Vipul Amrutlal Shah Cast: Salman Khan, Ajay Devgan, Asin, THE COURAGEOUS HEART Make-Up and Hair Department Head OF IRENA SENDLER Director: John Kent Harrison Hallmark Hall of Fame Cast: Anna Paquin, Goran Visnjic, Marcia Gay Harden Winner: Emmy for Outstanding Make-Up for a Miniseries or Movie -

October 2019

FILMS RATED/CLASSIFIED From 01 Oct 2019 to 31 Oct 2019 Films and Trailers FILM TITLE DIRECTOR RUN TIME DATE APPROVED DESCRIPTION MEDIA NAME #AnneFrank. Parallel Stories Sabina Fedeli/Anna 2.07 22/10/2019 PG Trailer Migotto 1917 Sam Mendes 2.27 15/10/2019 M Trailer 3 From Hell Rob Zombie 115.49 18/10/2019 R18 Graphic violence, sexual violence, horror & offensive language Film - DCP Abominable Jill Culton, Todd 97 24/10/2019 G Film - DVD Wilderman Ad Astra James Gray 122.55 8/10/2019 M Violence, offensive language & content that may disturb Film - DVD Addams Family, The Greg Tiernan, 86.58 17/10/2019 PG Coarse language Film - DCP Conrad Vernon Aeronauts, The Tom Harper 100.23 8/10/2019 PG Film - DCP All at Sea Robert Young 88.2 10/10/2019 M Film - DCP Am Cu Ce Pride Hannah 19 25/10/2019 PG Offensive language Film - DCP Weissenborn André Rieu: 70 Years Young André Rieu and 1 15/10/2019 G Trailer Michael Wiseman Angel Has Fallen Ric Roman Waugh 121 7/10/2019 R16 Violence & offensive language Film - Harddrive Arctic Justice Aaron Woodley 92 24/10/2019 G Film - DCP Ardab Mutiyaran Manav Shah 139.3 15/10/2019 PG Violence & coarse language Film - DCP At Last Yiwei Liu 1.05 22/10/2019 M Trailer Badlands Terrence Malick 93.37 15/10/2019 M Violence Film - DCP Bala Amar Kaushik 2.47 22/10/2019 M Sexual references Trailer Barefoot Bandits, The: Behind the Voices Ryan Cooper, Alex 4.56 4/10/2019 G Film - DCP Leighton, Tim Evans Barefoot Bandits, The: Glow Your Own Way Comp Ryan Cooper, Alex 0.31 4/10/2019 G Film - DCP Leighton, Tim Evans For Further -

Theaters 3 & 4 the Grand Lodge on Peak 7

The Grand Lodge on Peak 7 Theaters 3 & 4 NOTE: 3D option is only available in theater 3 Note: Theater reservations are for 2 hours 45 minutes. Movie durations highlighted in Orange are 2 hours 20 minutes or more. Note: Movies with durations highlighted in red are only viewable during the 9PM start time, due to their excess length Title: Genre: Rating: Lead Actor: Director: Year: Type: Duration: (Mins.) The Avengers: Age of Ultron 3D Action PG-13 Robert Downey Jr. Joss Whedon 2015 3D 141 Born to be Wild 3D Family G Morgan Freeman David Lickley 2011 3D 40 Captain America : The Winter Soldier 3D Action PG-13 Chris Evans Anthony Russo/ Jay Russo 2014 3D 136 The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader 3D Adventure PG Georgie Henley Michael Apted 2010 3D 113 Cirque Du Soleil: Worlds Away 3D Fantasy PG Erica Linz Andrew Adamson 2012 3D 91 Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2 3D Animation PG Ana Faris Cody Cameron 2013 3D 95 Despicable Me 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2010 3D 95 Despicable Me 2 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2013 3D 98 Finding Nemo 3D Animation G Ellen DeGeneres Andrew Stanton 2003 3D 100 Gravity 3D Drama PG-13 Sandra Bullock Alfonso Cuaron 2013 3D 91 Hercules 3D Action PG-13 Dwayne Johnson Brett Ratner 2014 3D 97 Hotel Transylvania Animation PG Adam Sandler Genndy Tartakovsky 2012 3D 91 Ice Age: Continetal Drift 3D Animation PG Ray Romano Steve Martino 2012 3D 88 I, Frankenstein 3D Action PG-13 Aaron Eckhart Stuart Beattie 2014 3D 92 Imax Under the Sea 3D Documentary G Jim Carrey Howard Hall -

Productions in Ontario 2006

2006 PRODUCTION IN ONTARIO with assistance from Ontario Media Development Corporation www.omdc.on.ca You belong here FEATURE FILMS – THEATRICAL ANIMAL 2 AWAY FROM HER Company: DGP Animal Productions Inc. Company: Pulling Focus Pictures ALL HAT Producers: Lewin Webb, Kate Harrison, Producer: Danny Iron, Simone Urdl, Company: No Cattle Productions Inc./ Wayne Thompson, Jennifer Weiss New Real Films David Mitchell, Erin Berry Director: Sarah Polley Producer: Jennifer Jonas Director: Ryan Combs Writers: Sarah Polley, Alice Munro Director: Leonard Farlinger Writer: Jacob Adams Production Manager: Ted Miller Writer: Brad Smith Production Manager: Dallas Dyer Production Designer: Kathleen Climie Line Producer/Production Manager: Production Designer: Andrew Berry Director of Photography: Luc Montpellier Avi Federgreen Director of Photography: Brendan Steacy Key Cast: Gordon Pinsent, Julie Christie, Production Designer: Matthew Davies Key Cast: Ving Rhames, K.C. Collins Olympia Dukakis Director of Photography: Paul Sarossy Shooting Dates: November – December 2006 Shooting Dates: February – April 2006 Key Cast: Luke Kirby, Rachael Leigh Cook, Lisa Ray A RAISIN IN THE SUN BLAZE Shooting Dates: October – November 2006 Company: ABC Television/Cliffwood Company: Barefoot Films GMBH Productions Producers: Til Schweiger, Shannon Mildon AMERICAN PIE PRESENTS: Producer: John Eckert Executive Producer: Tom Zickler THE NAKED MILE Executive Producers: Craig Zadan, Neil Meron Director: Reto Salimbeni Company: Universal Pictures Director: Kenny Leon Writer: Reto Salimbeni Producer: W.K. Border Writers: Lorraine Hansberry, Paris Qualles Line Producer/Production Manager: Director: Joe Nussbaum Production Manager: John Eckert Lena Cordina Writers: Adam Herz, Erik Lindsay Production Designer: Karen Bromley Production Designer: Matthew Davies Line Producer/Production Manager: Director of Photography: Ivan Strasburg Director of Photography: Paul Sarossy Byron Martin Key Cast: Sean Patrick Thomas, Key Cast: Til Schweiger Production Designer: Gordon Barnes Sean ‘P. -

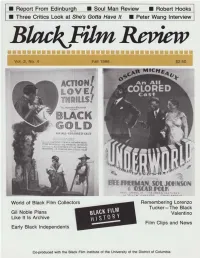

Report from Edinbur H • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview

Report From Edinbur h • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview World of Black Film Collectors Remembering Lorenzo Tucker- The Black. Gil Noble Plans Valentino Like It Is Archive Film Clips and News Early Black Independents Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Vol. 2, No. 4/Fa111986 'Peter Wang Breaks Cultural Barriers Black Film Review by Pat Aufderheide 10 SSt., NW An Interview with the director of A Great Wall p. 6 Washington, DC 20001 (202) 745-0455 Remembering lorenzo Tucker Editor and Publisher by Roy Campanella, II David Nicholson A personal reminiscence of one of the earliest stars of black film. ... p. 9 Consulting Editor Quick Takes From Edinburgh Tony Gittens by Clyde Taylor (Black Film Institute) Filmmakers debated an and aesthetics at the Edinburgh Festival p. 10 Associate EditorI Film Critic Anhur Johnson Film as a Force for Social Change Associate Editors by Charles Burnett Pat Aufderheide; Keith Boseman; Excerpts from a paper delivered at Edinburgh p. 12 Mark A. Reid; Saundra Sharp; A. Jacquie Taliaferro; Clyde Taylor Culture of Resistance Contributing Editors Excerpts from a paper p. 14 Bill Alexander; Carroll Parrott Special Section: Black Film History Blue; Roy Campanella, II; Darcy Collector's Dreams Demarco; Theresa furd; Karen by Saundra Sharp Jaehne; Phyllis Klotman; Paula Black film collectors seek to reclaim pieces of lost heritage p. 16 Matabane; Spencer Moon; An drew Szanton; Stan West. With a repon on effons to establish the Like It Is archive p. -

Global Cinema

GLOBAL CINEMA Edited by Katarzyna Marciniak, Anikó Imre, and Áine O’Healy The Global Cinema series publishes innovative scholarship on the transnational themes, industries, economies, and aesthetic elements that increasingly connect cinemas around the world. It promotes theoretically transformative and politi- cally challenging projects that rethink film studies from cross-cultural, comparative perspectives, bringing into focus forms of cinematic production that resist nation- alist or hegemonic frameworks. Rather than aiming at comprehensive geographical coverage, it foregrounds transnational interconnections in the production, dis- tribution, exhibition, study, and teaching of film. Dedicated to global aspects of cinema, this pioneering series combines original perspectives and new method- ological paths with accessibility and coverage. Both “global” and “cinema” remain open to a range of approaches and interpretations, new and traditional. Books pub- lished in the series sustain a specific concern with the medium of cinema but do not defensively protect the boundaries of film studies, recognizing that film exists in a converging media environment. The series emphasizes a historically expanded rather than an exclusively presentist notion of globalization; it is mindful of reposi- tioning “the global” away from a US-centric/Eurocentric grid, and remains critical of celebratory notions of “globalizing film studies.” Katarzyna Marciniak is a professor of Transnational Studies in the English Depart- ment at Ohio University. Anikó Imre is an associate -

Robert Burns Centre FILM THEATRE BOX OFFICE 01387 264808 MAY to JULY 2011

Robert Burns Centre FILM THEATRE BOX OFFICE 01387 264808 WWW.RBCFT.CO.UK MAY to JULY 2011 29APRIL 07MAY 2011 INCLUDING DUMFRIES FILM FESTIVAL in local cinemas across the region PIRATES OF THE PROGRAMME CARIBBEAN Submarine Source Code Armadillo Essential Killing The African Queen 13 Assassins The Conspirator Welcome Welcome to the fifth Dumfries Film Festival – an intense week of film across Dumfries and Galloway with local cinema screenings in Dumfries, Moffat, Annan and the Isle of Whithorn. We’ve been on a diet since last year’s bumper food themed festival and have slimmed down a bit (less funding these days). Focussing on quality rather than quantity we have a fantastic array of films, quizzes and events to entertain all ages with a special youth strand running though the week – young programmers, young characters, young production companies and films for young people (and for all of us still young at heart too). We hope that you will you will spring into film and enjoy! Fiona Wilson (Film Officer) and Darren Connor (Guest Programmer) …….filling in for Film Officer Alice Stilgoe who while on maternity leave enjoying quality time with baby girl Bonnie, still managed to do sterling work programming most of this festival for your enjoyment. 29APRIL 07MAY 2011 Young Programmers’ Forum Spring 2011: Alex Bryant • Cameron Forbes • Luke Maloney • Connor McMorran • Ruth Swift-Wood • David Barker • Tom Archer • Lauren Halliday • Beth Ashby • Danielle Welsh • James Pickering Four Young Programmer’s Choice screenings at RBCFT are the culmination of a six-week course for young people aged 16-24 that explored film programming. -

Here to Play Back Faithfully in Any Theatre

399644_CAS_QuarterlyMagazineAwards_Ad.indd 1 HBO® CONGRATULATES OUR 49TH CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARDS WINNER Jamie Ledner Brian Riordan,CAS ©2013 HomeBoxOffice,Inc. Allrightsreserved.HBO FOR YOURRECOGNITION THANK YOU,CASMEMBERS, FAME INDUCTIONCEREMONY THE 2012ROCK&ROLLHALLOF SERIES ORSPECIALS VARIETY ORMUSIC TELEVISION NON-FICTION, ® andrelatedchannelsservice marksarethepropertyofHomeBoxOffice,Inc. 4/22/13 5:41 PM MORE POWERFUL STORYTELLING BRINGS YOUR VISION TO LIFE Hear what industry professionals say about Dolby® Atmos™. EXPANDS THE ARTISTIC PALETTE Place and move sound anywhere to play back faithfully in any theatre. “I strive to make movies that allow the audience to participate in the events onscreen, rather than just watch them unfold. Wonderful technology is now available to support this goal: high frame rates, 3D, and now the stunning Dolby Atmos system. Dolby has always been at the cutting edge of providing cinema audiences with the ultimate sound experience, and they have now surpassed them- selves. Dolby Atmos provides the completely immersive sound experience that filmmakers like myself have long dreamed about.” —Peter Jackson, Co-Writer, Director, and Producer The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey SIMPLIFIES AUDIO POSTPRODUCTION Automatically generate 5.1, 7.1, and other delivery formats from the Dolby Atmos mix. “We needed a workflow that matched what we use already for Dolby Atmos to work for The Hobbit in the timeframe we had. Dolby had really great ideas for integration and developed the tools we needed for a bulletproof process.” —Gilbert Lake, Dolby Atmos Rerecording Mixer The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey See the full list of Dolby Atmos titles at dolby.com/atmosmovies. Dolby and the double-D symbol are registered trademarks of Dolby Laboratories.