Chapter 20 Castlepollard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midlands-Our-Past-Our-Pleasure.Pdf

Guide The MidlandsIreland.ie brand promotes awareness of the Midland Region across four pillars of Living, Learning, Tourism and Enterprise. MidlandsIreland.ie Gateway to Tourism has produced this digital guide to the Midland Region, as part of suite of initiatives in line with the adopted Brand Management Strategy 2011- 2016. The guide has been produced in collaboration with public and private service providers based in the region. MidlandsIreland.ie would like to acknowledge and thank those that helped with research, experiences and images. The guide contains 11 sections which cover, Angling, Festivals, Golf, Walking, Creative Community, Our Past – Our Pleasure, Active Midlands, Towns and Villages, Driving Tours, Eating Out and Accommodation. The guide showcases the wonderful natural assets of the Midlands, celebrates our culture and heritage and invites you to discover our beautiful region. All sections are available for download on the MidlandsIreland.ie Content: Images and text have been provided courtesy of Áras an Mhuilinn, Athlone Art & Heritage Limited, Athlone, Institute of Technology, Ballyfin Demense, Belvedere House, Gardens & Park, Bord na Mona, CORE, Failte Ireland, Lakelands & Inland Waterways, Laois Local Authorities, Laois Sports Partnership, Laois Tourism, Longford Local Authorities, Longford Tourism, Mullingar Arts Centre, Offaly Local Authorities, Westmeath Local Authorities, Inland Fisheries Ireland, Kilbeggan Distillery, Kilbeggan Racecourse, Office of Public Works, Swan Creations, The Gardens at Ballintubbert, The Heritage at Killenard, Waterways Ireland and the Wineport Lodge. Individual contributions include the work of James Fraher, Kevin Byrne, Andy Mason, Kevin Monaghan, John McCauley and Tommy Reynolds. Disclaimer: While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy in the information supplied no responsibility can be accepted for any error, omission or misinterpretation of this information. -

National Library of Ireland

ABOUT TOWN (DUNGANNON) AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) No. 1, May - Dec. 1986 Feb. 1950- April 1951 Jan. - June; Aug - Dec. 1987 Continued as Jan.. - Sept; Nov. - Dec. 1988 AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Jan. - Aug; Oct. 1989 May 1951 - Dec. 1971 Jan, Apr. 1990 April 1972 - April 1975 All Hardcopy All Hardcopy Misc. Newspapers 1982 - 1991 A - B IL B 94109 ADVERTISER (WATERFORD) AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Mar. 11 - Sept. 16, 1848 - Microfilm See AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) ADVERTISER & WATERFORD MARKET NOTE ALLNUTT'S IRISH LAND SCHEDULE (WATERFORD) (DUBLIN) March 4 - April 15, 1843 - Microfilm No. 9 Jan. 1, 1851 Bound with NATIONAL ADVERTISER Hardcopy ADVERTISER FOR THE COUNTIES OF LOUTH, MEATH, DUBLIN, MONAGHAN, CAVAN (DROGHEDA) AMÁRACH (DUBLIN) Mar. 1896 - 1908 1956 – 1961; - Microfilm Continued as 1962 – 1966 Hardcopy O.S.S. DROGHEDA ADVERTISER (DROGHEDA) 1967 - May 13, 1977 - Microfilm 1909 - 1926 - Microfilm Sept. 1980 – 1981 - Microfilm Aug. 1927 – 1928 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1982 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1929 - Microfilm 1983 - Microfilm Incorporated with DROGHEDA ARGUS (21 Dec 1929) which See. - Microfilm ANDERSONSTOWN NEWS (ANDERSONSTOWN) Nov. 22, 1972 – 1993 Hardcopy O.S.S. ADVOCATE (DUBLIN) 1994 – to date - Microfilm April 14, 1940 - March 22, 1970 (Misc. Issues) Hardcopy O.S.S. ANGLO CELT (CAVAN) Feb. 6, 1846 - April 29, 1858 ADVOCATE (NEW YORK) Dec. 10, 1864 - Nov. 8, 1873 Sept. 23, 1939 - Dec. 25th, 1954 Jan. 10, 1885 - Dec. 25, 1886 Aug. 17, 1957 - Jan. 11, 1958 Jan. 7, 1887 - to date Hardcopy O.S.S. (Number 5) All Microfilm ADVOCATE OR INDUSTRIAL JOURNAL ANOIS (DUBLIN) (DUBLIN) Sept. 2, 1984 - June 22, 1996 - Microfilm Oct. 28, 1848 - Jan 1860 - Microfilm ANTI-IMPERIALIST (DUBLIN) AEGIS (CASTLEBAR) Samhain 1926 June 23, 1841 - Nov. -

Publications

Publications National Newspapers Evening Echo Irish Examiner Sunday Business Post Evening Herald Irish Field Sunday Independent Farmers Journal Irish Independent Sunday World Irish Daily Star Irish Times Regional Newspapers Anglo Celt Galway City Tribune Nenagh Guardian Athlone Topic Gorey Echo New Ross Echo Ballyfermot Echo Gorey Guardian New Ross Standard Bray People Inish Times Offaly Express Carlow Nationalist Inishowen Independent Offaly Independent Carlow People Kerryman Offaly Topic Clare Champion Kerry’s Eye Roscommon Herald Clondalkin Echo Kildare Nationalist Sligo Champion Connacht Tribune Kildare Post Sligo Weekender Connaught Telegraph Kilkenny People South Tipp Today Corkman Laois Nationalist Southern Star Donegal Democrat Leinster Express Tallaght Echo Donegal News Leinster Leader The Argus Donegal on Sunday Leitrim Observer The Avondhu Donegal People’s Press Letterkenny Post The Carrigdhoun Donegal Post Liffey Champion The Nationalist Drogheda Independent Limerick Chronnicle Tipperary Star Dublin Gazette - City Limerick Leader Tuam Herald Dublin Gazette - North Longford Leader Tullamore Tribune Dublin Gazette - South Lucan Echo Waterford News & Star Dublin Gazette - West Lucan Echo Western People Dundalk Democrat Marine Times Westmeath Examiner Dungarvan Leader Mayo News Westmeath Independent Dungarvan Observer Meath Chronnicle Westmeath Topic Enniscorthy Echo Meath Topic Wexford Echo Enniscorthy Guardian Midland Tribune Wexford People Fingal Independent Munster Express Wicklow People Finn Valley Post Munster Express Magazines -

The Government's Executions Policy During the Irish Civil

THE GOVERNMENT’S EXECUTIONS POLICY DURING THE IRISH CIVIL WAR 1922 – 1923 by Breen Timothy Murphy, B.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: Professor Marian Lyons Supervisor of Research: Dr. Ian Speller October 2010 i DEDICATION To my Grandparents, John and Teresa Blake. ii CONTENTS Page No. Title page i Dedication ii Contents iii Acknowledgements iv List of Abbreviations vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The ‗greatest calamity that could befall a country‘ 23 Chapter 2: Emergency Powers: The 1922 Public Safety Resolution 62 Chapter 3: A ‗Damned Englishman‘: The execution of Erskine Childers 95 Chapter 4: ‗Terror Meets Terror‘: Assassination and Executions 126 Chapter 5: ‗executions in every County‘: The decentralisation of public safety 163 Chapter 6: ‗The serious situation which the Executions have created‘ 202 Chapter 7: ‗Extraordinary Graveyard Scenes‘: The 1924 reinterments 244 Conclusion 278 Appendices 299 Bibliography 323 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to extend my most sincere thanks to many people who provided much needed encouragement during the writing of this thesis, and to those who helped me in my research and in the preparation of this study. In particular, I am indebted to my supervisor Dr. Ian Speller who guided me and made many welcome suggestions which led to a better presentation and a more disciplined approach. I would also like to offer my appreciation to Professor R. V. Comerford, former Head of the History Department at NUI Maynooth, for providing essential advice and direction. Furthermore, I would like to thank Professor Colm Lennon, Professor Jacqueline Hill and Professor Marian Lyons, Head of the History Department at NUI Maynooth, for offering their time and help. -

VA14.4.015 – Pat Davitt C/O All Fit

Appeal No.VA14/4/015 AN BINSE LUACHÁLA VALUATION TRIBUNAL AN tACHT LUACHÁLA, 2001 VALUATION ACT, 2001 Mr Pat Davitt c/o All Fit Gym APPELLANT And Commissioner of Valuation RESPONDENT In Relation to the Issue of Quantum of Valuation in Respect of: Property No. 2212880, Gymnasium, at Lot No. 2C/Unit 8, Castlepollard Shopping Centre, Oldcastle Road, Castlepollard, Co. Westmeath. JUDGMENT OF THE VALUATION TRIBUNAL ISSUED ON THE 11th DAY OF NOVEMBER, 2015 Before Stephen J. Byrne – BL - Deputy Chairperson Michael Lyng – Valuer - Member Carol O'Farrell – BL - Member By Notice of Appeal received on the 12th day of November, 2014 the Appellant appealed against the determination of the Commissioner of Valuation in fixing a rateable valuation of €26 on the above described relevant property on the grounds as set out in the Notice of Appeal as follows: "For a building on the first floor with access from Ground floor in a small town of 1200 population the valuation I feel is very high. The shop under this gym on the ground floor has a Rateable Valuation of €21 which is 20% less" 2 This appeal proceeded by way of an oral hearing held in the offices of the Tribunal, on the 3rd floor of Holbrook House, Holles Street, Dublin 2, on the 18th day of March 2015 at 10 a.m. The Appellant was represented by Mr. Pat Davitt, Auctioneer and Valuer and the Respondent was represented by Ms. Ciara Hayes, Valuer at the Valuation Office. The Property Concerned The subject property comprises first floor accommodation which is accessed via a stairwell. -

![[ 17 ] Report of the Irish Poor Law Commission](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7250/17-report-of-the-irish-poor-law-commission-1707250.webp)

[ 17 ] Report of the Irish Poor Law Commission

[ 17 ] REPORT OF THE IRISH POOR LAW COMMISSION. BY CHARLES EASON, M.A. [Read before the Society on Thursday. 26th January, 1928.] The reform of the Irish Poor Law is a slow process. The attention of the public was first called to the need of reform by a paper read by the late Dr. Moorhead, Medical Officer of the Cootehill Workhouse, before the Irish Medical Association in January, 1895, in which he gave a summary of the replies that he had received from seventy-nine Unions. The Local Government Board then issued a circular, and the replies from forty-five Unions were summarised by Dr. Moorhead in another paper read before the Irish Medical Association in , August, 1895. A special Commissioner was then sent to Ire- land by the British Medical Journal. His reports appeared weekly and were published in a pamphlet in April, 1896. This was followed by the formation of the Irish Workhouse Asso- ciation in January, 1897, the late- Lord Monteagle being Pre- sident. In response to an appeal from this Association the Irish Catholic Bishops, in June, 1897, passed a resolution con- demning pauper nursing and recommending the appointment of trained nurses^ and in September the Local Government Board issued a general order with a view to compelling the employ- ment of trained nurses. In 1903 a Viceregal Commission to enquire into the Poor Law system was appointed, and,it reported in 1906, and this was followed in 1909 by the Report of a Royal Commission upon the Poor Law in\the United Kingdom. Nothing was done to give effect to the recommendations of these reports. -

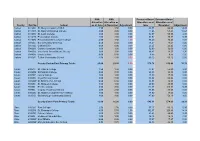

County Roll No School SNA Allocation As at June SNA Allocation As At

SNA SNA Resource Hours Resource Hours Allocation Allocation as Allocation as at Allocation as at County Roll No School as at June at November Adjustment June November Adjustment Carlow 61120E St. Mary's Academy C.B.S. 1.50 1.50 0.00 49.55 64.00 14.45 Carlow 61130H St. Mary's Knockbeg College 3.00 3.00 0.00 47.65 58.28 10.63 Carlow 61140K St. Leo's College 3.00 3.00 0.00 52.57 55.55 2.98 Carlow 61141M Presentation College 2.00 2.00 0.00 83.92 89.87 5.95 Carlow 61150N Presentation/De La Salle College 4.50 3.50 -1.00 75.40 75.40 0.00 Carlow 70400L Borris Vocational School 2.50 2.50 0.00 76.57 76.57 0.00 Carlow 70410O Coláiste Eóin 0.00 0.00 0.00 23.25 23.25 0.00 Carlow 70420R Carlow Vocational School 1.00 1.00 0.00 72.00 72.00 0.00 Carlow 70430U Vocational School Muine Bheag 3.00 3.00 0.00 16.87 18.57 1.70 Carlow 70440A Gaelcholáiste 0.00 0.00 0.00 9.85 9.85 0.00 Carlow 91356F Tullow Community School 4.50 4.00 -0.50 69.12 69.12 0.00 County Carlow Post Primary Totals 25.00 23.50 -1.50 576.76 612.46 35.70 Cavan 61051L St. Clare's College 1.50 1.50 0.00 47.07 56.00 8.93 Cavan 61060M St Patricks College 0.00 0.00 0.00 29.85 35.80 5.95 Cavan 61070P Loreto College 1.00 1.00 0.00 27.30 27.30 0.00 Cavan 61080S Royal School Cavan 3.00 3.00 0.00 53.22 53.22 0.00 Cavan 70350W St. -

Joint Committee on Communications, Climate Action And

Joint Committee on Communications, Climate Action and Environment ______________________ Submission by Independent News & Media plc ______________________ 6th February 2017 Independent House, 27-32 Talbot Street, Dublin 1 | www.inmplc.com EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Independent News & Media plc (“INM”) has been invited to address the Joint Committee on Communications, Climate Action and Environment in relation to the media merger examination of the proposed acquisition of CMNL Limited (“CMNL”), formerly Celtic Media Newspapers Limited, by INM (Independent News & Media Holdings Limited) by the Broadcasting Authority of Ireland (“BAI”). 2. The agreement for the sale and purchase of the entire issued share capital of CMNL Limited by INM was executed on 2nd September 2016. In line with the media merger requirements detailed in the Competition Acts 2002-2014, INM and CMNL jointly submitted a notification to the Competition and Consumer Protection Commission (“CCPC”) on 5th September 2016. On 10th November 2016 the CCPC determined that the transaction would not lead to a substantial lessening of competition in any market for goods or services in the State and the transaction could be put into effect subject to the provisions of 28C(1) of the Competition Acts 2002-20141. 3. On 21st November 2016, INM and CMNL jointly notified the Minister of Communications, Climate Action and Environment of the Proposed Transaction seeking approval and outlining the reasons why the Proposed Transaction would not be contrary to the public interest in protecting plurality of media in the State. On 10th January 2017, the Minister informed the parties of his decision to request the BAI to undertake a review as provided for in Section 28D(1)(c) of the Competition Acts 2002- 2014. -

News Distribution Via the Internet and Other New Ict Platforms

NEWS DISTRIBUTION VIA THE INTERNET AND OTHER NEW ICT PLATFORMS by John O ’Sullivan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MA by Research School of Communications Dublin City University September 2000 Supervisor: Mr Paul McNamara, Head of School I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of MA in Communications, is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others, save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. I LIST OF TABLES Number Page la, lb Irish Internet Population, Active Irish Internet Population 130 2 Average Internet Usage By Country, May 2000 130 3 Internet Audience by Gender 132 4 Online Properties in National and Regional/Local Media 138 5 Online Properties in Ex-Pat, Net-only, Radio-related and Other Media 139 6 Journalists’ Ranking of Online Issues 167 7 Details of Relative Emphasis on Issues of Online Journalism 171 Illustration: ‘The Irish Tex’ 157 World Wide Web references: page numbers are not included for articles that have been sourced on the World Wide Web, and where a URL is available (e.g. Evans 1999). ACKNOWLEDGMENTS With thanks and appreciation to Emer, Jack and Sally, for love and understanding, and to my colleagues, fellow students and friends at DCU, for all the help and encouragement. Many thanks also to those who agreed to take part in the interviews. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. I n t r o d u c t i o n ......................................................................................................................................................6 2. -

The List of Church of Ireland Parish Registers

THE LIST of CHURCH OF IRELAND PARISH REGISTERS A Colour-coded Resource Accounting For What Survives; Where It Is; & With Additional Information of Copies, Transcripts and Online Indexes SEPTEMBER 2021 The List of Parish Registers The List of Church of Ireland Parish Registers was originally compiled in-house for the Public Record Office of Ireland (PROI), now the National Archives of Ireland (NAI), by Miss Margaret Griffith (1911-2001) Deputy Keeper of the PROI during the 1950s. Griffith’s original list (which was titled the Table of Parochial Records and Copies) was based on inventories returned by the parochial officers about the year 1875/6, and thereafter corrected in the light of subsequent events - most particularly the tragic destruction of the PROI in 1922 when over 500 collections were destroyed. A table showing the position before 1922 had been published in July 1891 as an appendix to the 23rd Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records Office of Ireland. In the light of the 1922 fire, the list changed dramatically – the large numbers of collections underlined indicated that they had been destroyed by fire in 1922. The List has been updated regularly since 1984, when PROI agreed that the RCB Library should be the place of deposit for Church of Ireland registers. Under the tenure of Dr Raymond Refaussé, the Church’s first professional archivist, the work of gathering in registers and other local records from local custody was carried out in earnest and today the RCB Library’s parish collections number 1,114. The Library is also responsible for the care of registers that remain in local custody, although until they are transferred it is difficult to ascertain exactly what dates are covered. -

De Vesci Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 89 DE VESCI PAPERS (Accession No. 5344) Papers relating to the family and landed estates of the Viscounts de Vesci. Compiled by A.P.W. Malcomson; with additional listings prepared by Niall Keogh CONTENTS INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...........................................................6 I TITLE DEEDS, C.1533-1835 .........................................................................................19 I.i Muschamp estate, County Laois, 1552-1800 ............................................................................................19 I.ii Muschamp estates (excluding County Laois), 1584-1716........................................................................20 I.iii Primate Boyle’s estates, 1666-1835.......................................................................................................21 I.iv Miscellaneous title deeds to other properties c.1533-c. 1810..............................................................22 II WILLS, SETTLEMENTS, LEASES, MORTGAGES AND MISCELLANEOUS DEEDS, 1600-1984 ..................................................................................................................23 II.i Wills and succession duty papers, 1600-1911 ......................................................................................23 II.ii Settlements, mortgages and miscellaneous deeds, 1658-1984 ............................................................27 III LEASES, 1608-1982 ........................................................................................................35 -

Abstract Potent Legacies: the Transformation of Irish

ABSTRACT POTENT LEGACIES: THE TRANSFORMATION OF IRISH AMERICAN POLITICS, 1815-1840 Mathieu W. Billings, Ph.D. Department of History Northern Illinois University, 2016 Sean Farrell, Director This dissertation explores what “politics” meant to Irish and Irish American Catholic laborers between 1815 and 1840. Historians have long remembered emigrants of the Emerald Isle for their political acumen during the 19th century—principally their skills in winning municipal office and mastering “machine” politics. They have not agreed, however, about when, where, and how the Irish achieved such mastery. Many scholars have argued that they obtained their political educations in Ireland under the tutelage of Daniel O’Connell, whose mass movement in the 1820s brought about Catholic Emancipation. Others have claimed that, for emigrant laborers in particular, their educations came later, after the Famine years of the late 1840s, and that they earned them primarily in the United States. In this dissertation, I address this essential discrepancy by studying their experiences in both Ireland and America. Primarily utilizing court records, state documents, company letters, and newspapers, I argue that Irish Catholic laborers began their educations in Ireland before emigrating in the late 1820s and early 1830s. Yet they completed them in America, particularly in states where liberal suffrage requirements permitted them to put their skills in majority rule to use. By 1840, both Whigs and Democrats alike recognized the political intellects of Irish-born laborers, and both vigorously courted their votes. Indeed, the potent legacies of their experiences in Ireland made many the unsung power brokers of the early republic. NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DE KALB, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2016 POTENT LEGACIES: THE TRANSFORMATION OF IRISH AMERICAN POLITICS, 1815-1840 BY MATHIEU W.