Practical Outlook on Gender Issues in the Water Resources Sector 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OPERATION SCHEME of the Executives of Sectors, Head Offices and Secretaries of Head Offices of Tashkent Region

OPERATION SCHEME of the Executives of Sectors, Head offices and secretaries of Head offices of Tashkent Region Sector 1 – Khokim’s Head office Sector 2 – Head office secretary of the Sector 3 –Head office secretary of the Sector 4 – Head office secretary of the secretary and location Prosecutor’s Office and location Department of Internal affairs (DIA) State Tax Inspectorate and location and location Khidoyatov Davron Abdulpattakhovich Samadov Salom Ismatovich Aripov Tokhir Tulkinovich Raimov Ravshan Isakjanovich KHOKIM OF THE REGION TASHKENT REGION PROSECUTOR MAIN DEPARTMENT OF INTERNAL STATE TAX INSPECTORATE OF HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: A. Eshbaev HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: М. Egamberdiev AFFAIRS OF TASHKENT REGION TASHKENT REGION Phone number: (98) 007-30-04 Phone number: (97) 733-57-37 HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: F. HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: E. Djumabaev Location: 1, Almalik city, Tashkent region. Location: 1, Tashkent yuli, Nurafshan city. Khamitov Phone number: (93) 398-54-34 Phone of the Head office: (70) 201-07-34 +6448 Phone number: (99) 301-70-77 Location: 79 A, Babur str., Tashkent. Location: Mevazor, Kuyichirchik region. Phone of the Head office: (78) 150-49-56 Phone of the Head office: (95) 476-75 -77 Saliyev Muzaffar Kholdorbolevich Mirzayev Fakhriddin Yusupovich Amanbaev Navruz Zokirjonovich Narkhodjaev Sanjar Rashidovich KHOKIM OF NURAFSHAN CITY PROSECUTOR OF NURAFSHAN CITY DIA OF NURAFSHAN CITY NURAFSHAN CITY STATE TAX HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: О. Erbaev HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: М.Shukrullaev HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: F. INSPECTORATE Phone number: (99) 823-67-72 Phone: (97) 911-77-10 Imankulov HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: E. Igamnazarov Location: Tashkent yuli str., Nurafshan city. Location: 4A, Shon shukhrat str., Obod turmush Phone: (94) 631-49-37 Phone: (94) 930-03-73 CCU, Nurafshan city. -

Agrotechnologies and Agricultural Industry

SCIENTIFIC COLLECTION «INTERCONF» | № 53 AGROTECHNOLOGIES AND AGRICULTURAL INDUSTRY Anarbayev Yermek A. PhD student of the 3rd year training Kazakh National Agrarian University, Republic of Kazakhstan Pentayev Toleubek Doctor of Technical Sciences, Professor Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Republic of Kazakhstan Molzhigitova Dinara K. PhD doctor, Associate Professor Kazakh National Agrarian University, Republic of Kazakhstan Omarbekova Ardak D. PhD doctor, Associate Professor Kazakh National Agrarian University, Republic of Kazakhstan Omarova Sholpan Zh. PhD doctor, Associate Professor Kazakh National Agrarian University, Republic of Kazakhstan RESEARCH OF AGRICULTURAL LANDS TAKING INTO ACCOUNT THE PECULIARITIES OF THEIR USE OF THE TURKESTAN REGION Abstract. In the article the issues of research and assessment of the qualitative condition of agricultural lands, taking into account the peculiarities of their use in the Turkestan region are considered. The increase in the production of agricultural products primarily depends on how rationally and skillfully the land is used; also, the complete and correct use of the land has the most important conditions for increasing the production of grain, milk, meat and other products. Research and production work should be aimed at solving these problems. Therefore, to begin with, it is very important to analyze the condition of agricultural land resources and outline ways to improve their use, taking into account the qualitative condition. Keywords: land resources, agricultural land, land valuation, quality condition of land, cadastral value of agricultural land, base rate, reactive income. 609 INTERNATIONAL FORUM: PROBLEMS AND SCIENTIFIC SOLUTIONS Introduction: The problem of rational use of lands extorts a wide range of activities. One of the priority research and applied areas is the effective use of the potential of land resources. -

Bitiruv Malakaviy Ishi

O’ZBЕKISTON RЕSPUBLIKASI OLIY VA O’RTA MAXSUS TA’LIM VAZIRLIGI NAMANGAN MUHANDISTLIK-QURILISH INSTITUTI “QURILISH” fakulteti “BINOLAR VA INSHOOTLAR QURILISHI” kafedrasi САМАТОВ АБДУМУТАЛ АБДУҚОДИР ЎҒЛИ ” Angren shaharida xududa namunaviy kam-qavatli turar- joy uylarini loyihasini me`moray rejalashtirish ” 5341000 «Qishloq hududlarini arxitektura-loyihaviy tashkil etish» Bakalavr darajasini olish uchun yozilgan BITIRUV MALAKAVIY ISHI Kafedra mudiri: dots.S.Abduraxmonov___________ Ilmiy rahbar: , к.ўқ A.Dadaboyev ___________ “_____”___________2018 y Namangan 2018 Kirish. O'zbekiston Respublikasi mustaqillikka erishgan davrdan boshlab hukumatimiz tomonidan arhitektura va shaharsozlik sohasiga katta e‘tibor berilib, shaharsozlik sohasi faoliyatida bir qator O'zbekiston Respublikasi Birinchi Prezidenti Farmonlari va Vazirlar Maxkamasining ushbu soha yuzasidan qarorlari qabul qilindi. O'zbekiston Respublikasi Birinchi Prezidentining ―O'zbekiston Respublikasida Arhitektura va shahar qurilishini yanada takomillashtirish chora- tadbirlari to'g'risida‖gi farmoni hamda ushbu farmon ijrosi yuzasidan Vazirlar Mahkamasining ―Arhitektura va qurilish sohasidagi ishlarni tashkil etish va nazoratni takomillashtirish chora-tadbirlari to'g'risida‖gi, ―Shaharlar, tuman markazlari va shahar tipidagi posyolkalarning bosh rejalarini ishlab chiqish va ularni qurish tartibi to'g'risidagi Nizomni tasdiqlash xaqida‖gi, ―Arhitektura va shaharsozlik sohasidagi qonun hujjatlariga rioya qilinishi uchun rahbarlar va mansabdor shahslarning javobgarligini oshirish chora-tadbirlari -

World Bank Document

Ministry of Agriculture and Uzbekistan Agroindustry and Food Security Agency (UZAIFSA) Public Disclosure Authorized Uzbekistan Agriculture Modernization Project Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Tashkent, Uzbekistan December, 2019 ABBREVIATIONS AND GLOSSARY ARAP Abbreviated Resettlement Action Plan CC Civil Code DCM Decree of the Cabinet of Ministries DDR Diligence Report DMS Detailed Measurement Survey DSEI Draft Statement of the Environmental Impact EHS Environment, Health and Safety General Guidelines EIA Environmental Impact Assessment ES Environmental Specialist ESA Environmental and Social Assessment ESIA Environmental and Social Impact Assessment ESMF Environmental and Social Management Framework ESMP Environmental and Social Management Plan FS Feasibility Study GoU Government of Uzbekistan GRM Grievance Redress Mechanism H&S Health and Safety HH Household ICWC Integrated Commission for Water Coordination IFIs International Financial Institutions IP Indigenous People IR Involuntary Resettlement LAR Land Acquisition and Resettlement LC Land Code MCA Makhalla Citizen’s Assembly MoEI Ministry of Economy and Industry MoH Ministry of Health NGO Non-governmental organization OHS Occupational and Health and Safety ОP Operational Policy PAP Project Affected Persons PCB Polychlorinated Biphenyl PCR Physical Cultural Resources PIU Project Implementation Unit POM Project Operational Manual PPE Personal Protective Equipment QE Qishloq Engineer -

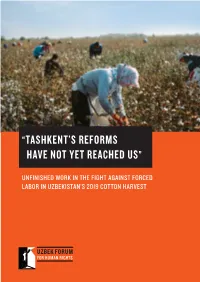

“Tashkent's Reforms Have Not

“TASHKENT’S REFORMS HAVE NOT YET REACHED US” UNFINISHED WORK IN THE FIGHT AGAINST FORCED LABOR IN UZBEKISTAN’S 2019 COTTON HARVEST “TASHKENT’S REFORMS HAVE NOT YET REACHED US” UNFINISHED WORK IN THE FIGHT AGAINST FORCED LABOR IN UZBEKISTAN’S 2019 COTTON HARVEST 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 KEY FINDINGS FROM THE 2019 HARVEST 6 METHODOLOGY 8 TABLE 1: PARTICIPATION IN THE COTTON HARVEST 10 POSITIVE TRENDS 12 FORCED LABOR LINKED TO GOVERNMENT POLICIES AND CONTROL 13 MAIN RECRUITMENT CHANNELS FOR COTTON PICKERS: 15 TABLE 2: PERCEPTION OF PENALTY FOR REFUSING TO PICK COTTON ACCORDING TO WHO RECRUITED RESPONDENTS 16 TABLE 3: WORKING CONDITIONS FOR PICKERS ACCORDING TO HOW THEY WERE RECRUITED TO PICK COTTON 16 TABLE 4: PERCEPTION OF COERCION BY RECRUITMENT METHODS 17 LACK OF FAIR AND EFFECTIVE RECRUITMENT SYSTEMS AND STRUCTURAL LABOR SHORTAGES 18 STRUCTURAL LABOR SHORTAGES 18 LACK OF FAIR AND EFFECTIVE RECRUITMENT SYSTEMS 18 FORCED LABOR MOBILIZATION 21 1. ABILITY TO REFUSE TO PICK COTTON 21 TABLE 5: ABILITY TO REFUSE TO PICK COTTON 21 TABLE 6: RESPONDENTS’ ABILITY TO REFUSE TO PICK COTTON ACCORDING TO HOW THEY WERE RECRUITED 22 2. MENACE OF PENALTY 22 TABLE 7: PENALTIES FOR REFUSAL 22 TABLE 8: PERCEIVED PENALTIES FOR REFUSAL TO PICK COTTON BY PROFESSION 23 3. REPLACEMENT FEES/EXTORTION 23 TABLE 9: FEES TO AVOID COTTON PICKING 23 CHART 1: PAYMENT OF FEES BY REGION 24 OFFICIALS FORCIBLY MOBILIZED LABOR FROM THE BEGINNING OF THE HARVEST TO MEET LABOR SHORTAGES 24 LAW ENFORCEMENT, MILITARY, AND EMERGENCIES PERSONNEL 24 PUBLIC UTILITIES -

Natural Resource Potential of Industrial Development of the Tashkent Economic District

Int. J. Agr. Ext. (2021). 111-118 | Special Issue DOI: 10.33687/ijae.009.00.3726 Available Online at EScience Press Journals International Journal of Agricultural Extension ISSN: 2311-6110 (Online), 2311-8547 (Print) http://www.esciencepress.net/IJAE NATURAL RESOURCE POTENTIAL OF INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE TASHKENT ECONOMIC DISTRICT aMamatkodir I. Nazarov*, aBekzod B. Rakhmanov, aSergey L. Yanchuk, aShuxrat B. Kurbanov, aSaida K. Tashtayeva, bZulhumor T. Abdalova aNational University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Republic of Uzbekistan. bTashkent State Pedagogical University named after Nizami, Tashkent, Republic of Uzbekistan. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History The key factors in the production development and location, including industrial Received: April 21, 2021 production, in any region, are the territorial structure of natural resources and the Revised: July 1, 2021 level of production infrastructure development. At present, the industry is one of the Accepted: July 30, 2021 leading sectors of the developed countries' economy. Therefore, the Government of Uzbekistan, from the first days of state independence, prioritises the industry Keywords development, its modernisation and diversification when reforming the national Sectoral structure economy. Due to this, over the past ten years, the industrial production share in the Factors of production country's GDP has grown significantly and amounts to almost 1/3 of it. However, the location participation of regions in gross industrial output is very uneven, and a number of Minerals them, in the presence of high natural resource potential, still retain agricultural Mineral material specialisation. The paper presents an economic and geographical analysis of natural Raw material potential resources as a factor of industrial development in the Tashkent economic district. -

Highlights Uzbekistan Covid-19 Situation Report 18

UZBEKISTAN COVID-19 SITUATION REPORT 18 FEBRUARY 2021 (DATA AS AT 11PM, PREVIOUS DAY) This Sitrep outlines current information on the COVID-19 outbreak in Uzbekistan, and summarizes international partners’ support to the nation- Total Cases: 79,548 Total Recovered: 78,059 Total Deaths: 622 Daily new cases: 51 Global Info: Text “Hi” to +41 79 893 18 92 (WhatsApp) for the latest WHO global updates and statistics. National Hotline: 1003 / 103 HIGHLIGHTS • Government holds briefing on COVID-19 vaccination EPIDEMIOLOGICAL UPDATE Cumulative cases by regions as of 17 February: Tashkent City: 46,305 (+33) Syrdarya: 1297 Tashkent region: 15,765 (+11) Surkhandarya: 1130 Namangan: 2735 (+5) Karakalpakstan: 877 Samarkand: 2578 Khorezm: 970 Andijan: 2309 (+2) Fergana: 881 Kashkadarya: 1639 Jizzakh: 861 Bukhara: 1484 Navoiy: 717 This chart shows the daily increase in confirmed new cases, as well as a 5-day moving average which helps smooth out the ‘noise’ from short-term fluctuations by averaging the data from the last five days reported. This map visualizes data as of 17 February 2021. SITREP CONTACT: To subscribe to or unsubscribe from this Sitrep, UN Office of the Resident Coordinator please click here. Liya Khalikova ([email protected]) UZBEKISTAN COVID-19 RESPONSE Situation Report | 18 February 2021 Epidemiological update (cont’d): New cases by region HEALTH RESPONSE • 11 February: +37. Tashkent City +19; Tashkent region Health Capacity-Building +11; Khorezm +3; Namangan +2; Karakalpakstan +1; • On 17 February, WHO Regional Office organized Surkhandarya +1. another joint online global consultation on Contact • 12 February: +41. Tashkent City +26; Surkhandarya +5; Tracing for COVID-19. -

QTL Mapping for Flowering-Time and Photoperiod Insensitivity of Cotton Gossypium Darwinii Watt

RESEARCH ARTICLE QTL mapping for flowering-time and photoperiod insensitivity of cotton Gossypium darwinii Watt Fakhriddin N. Kushanov1☯, Zabardast T. Buriev1, Shukhrat E. Shermatov1, Ozod S. Turaev1, Tokhir M. Norov1, Alan E. Pepper2, Sukumar Saha3, Mauricio Ulloa4, John Z. Yu5, Johnie N. Jenkins3, Abdusattor Abdukarimov1, Ibrokhim Y. Abdurakhmonov1☯* 1 Laboratory of Structural and Functional Genomics, Center of Genomics and Bioinformatics, Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 2 Department of Biology, Texas A&M a1111111111 University, Colleges Station, Texas, United States of America, 3 Crop Science Research Laboratory, United a1111111111 States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Services, Starkville, Mississippi, United States of a1111111111 America, 4 Plant Stress and Germplasm Development Research, United States Department of Agriculture- a1111111111 Agricultural Research Services, Lubbock, Texas, United States of America, 5 Southern Plains Agricultural a1111111111 Research Center, United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Services, College Station, Texas, United States of America ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Citation: Kushanov FN, Buriev ZT, Shermatov SE, Abstract Turaev OS, Norov TM, Pepper AE, et al. (2017) QTL mapping for flowering-time and photoperiod Most wild and semi-wild species of the genus Gossypium are exhibit photoperiod-sensitive insensitivity of cotton Gossypium darwinii Watt. PLoS ONE 12(10): e0186240. https://doi.org/ flowering. The wild germplasm cotton is a valuable source of genes for genetic improvement 10.1371/journal.pone.0186240 of modern cotton cultivars. A bi-parental cotton population segregating for photoperiodic Editor: Turgay Unver, Dokuz Eylul Universitesi, flowering was developed by crossing a photoperiod insensitive irradiation mutant line with TURKEY its pre-mutagenesis photoperiodic wild-type G. -

Third-Party Monitoring of Measures Against Child Labour and Forced Labour During the 2016 Cotton Harvest in Uzbekistan

Third-party monitoring of measures against child labour and forced labour during the 2016 cotton harvest in Uzbekistan A report submitted to the World Bank by the International Labour Office This report has been prepared by the ILO at the request of the World Bank for the third party monitoring of the World Bank-financed projects in agriculture, water and education sectors in Uzbekistan. The ILO is grateful for the cooperation of the tripartite constituents of Uzbekistan, and in particular the Federation of Trade Unions of Uzbekistan, in the monitoring and assessment process. The ILO has tried to reflect the constructive comments received from its partners throughout the process. In line with their request, it has formulated concrete suggestions for further work by the constituents, including cooperation involving the ILO and the World Bank. The ILO alone is responsible for the conclusions drawn in this report. January 2017 1 Key Findings Uzbekistan continues to make policy commitments and develop action plans to reduce the risks of child and forced labour. Government instructions were issued before and during both the 2015 and 2016 harvests. These are increasingly influencing the context within which officials and citizens view their involvement in the cotton harvest. Uzbekistan has phased-out organized child labour. ILO first monitored child labour during the 2013 cotton harvest. Since then, the risk has been reduced to the point at which child labour has become socially unacceptable, as noted in 2015 and again this year. This is a major Uzbek achievement, made possible by the availability of educational facilities. Vigilance will be required to ensure the ongoing efficacy of measures against child labour, especially for 16-17 year old pupils in lyceums and same age students in colleges. -

Trends and Features of Industrial Development in the Region (On the Example of Tashkent Region)

International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology Vol. 29, No. 9s, (2020), pp. 5381-5391 Trends And Features Of Industrial Development In The Region (On The Example Of Tashkent Region) Batirova Nilufar Sherkulovna, Senior lecturer of International Islamic Academy of Uzbekistan, Abstract The article analyzes the trends of industrial development of the region. Intensive factors of growth of industrial production are considered one by one. The state of basic funds in the development of industrial production in the region is studied. The region was also assessed on the basis of the impact of innovation and investment factors. The conclusion provides recommendations for eliminating the imbalance between the existing regions, accelerating the development of new high- tech industries of the industrial complex. Keywords: region, territory, region, valuation, fixed assets, innovation, technological innovation, modernization, science and technology, export, production, foreign capital. INTRODUCTION The development of the industry of each region using the modern achievements of science and technology is an urgent task today. The introduction of high technologies for modernization in food, fuel and machinery sectors in Tashkent region in recent years has ensured a steady growth of labor productivity in industry. The increase in industrial production capacity is leading to an increase in the share of industry in the GRP of the region. Modernization of industrial enterprises in the region and the introduction of high-efficiency technologies based on modern innovations is an urgent task today. The growth of industrial production is inculcates not due to the expansion of extensive factors, but due to a gradual consistent policy in a systemic market economy, attracting foreign investment, deep structural changes in the economy, modernization and renewal of production, the establishment of new export-oriented industries and enterprises, the development of private entrepreneurship. -

List of Districts of Uzbekistan

Karakalpakstan SNo District name District capital 1 Amudaryo District Mang'it 2 Beruniy District Beruniy 3 Chimboy District Chimboy 4 Ellikqala District Bo'ston 5 Kegeyli District* Kegeyli 6 Mo'ynoq District Mo'ynoq 7 Nukus District Oqmang'it 8 Qonliko'l District Qanliko'l 9 Qo'ng'irot District Qo'ng'irot 10 Qorao'zak District Qorao'zak 11 Shumanay District Shumanay 12 Taxtako'pir District Taxtako'pir 13 To'rtko'l District To'rtko'l 14 Xo'jayli District Xo'jayli Xorazm SNo District name District capital 1 Bog'ot District Bog'ot 2 Gurlen District Gurlen 3 Xonqa District Xonqa 4 Xazorasp District Xazorasp 5 Khiva District Khiva 6 Qo'shko'pir District Qo'shko'pir 7 Shovot District Shovot 8 Urganch District Qorovul 9 Yangiariq District Yangiariq 10 Yangibozor District Yangibozor Navoiy SNo District name District capital 1 Kanimekh District Kanimekh 2 Karmana District Navoiy 3 Kyzyltepa District Kyzyltepa 4 Khatyrchi District Yangirabad 5 Navbakhor District Beshrabot 6 Nurata District Nurata 7 Tamdy District Tamdibulok 8 Uchkuduk District Uchkuduk Bukhara SNo District name District capital 1 Alat District Alat 2 Bukhara District Galaasiya 3 Gijduvan District Gijduvan 4 Jondor District Jondor 5 Kagan District Kagan 6 Karakul District Qorako'l 7 Karaulbazar District Karaulbazar 8 Peshku District Yangibazar 9 Romitan District Romitan 10 Shafirkan District Shafirkan 11 Vabkent District Vabkent Samarqand SNo District name District capital 1 Bulungur District Bulungur 2 Ishtikhon District Ishtikhon 3 Jomboy District Jomboy 4 Kattakurgan District -

Evaluation of the 3Rd and 4Th UNFPA Country Programme for Kazakhstan (2010-2018) EVALUATION REPORT

Evaluation of the 3rd and 4th UNFPA Country Programme for Kazakhstan (2010-2018) EVALUATION REPORT November, 2019 EVALUATION REPORT: The 3rd and 4th UNFPA Country Programmes for Kazakhstan (2010-2018) Kazakhstan Country Map1 Evaluation team Evaluation Team Leader Lyubov Palyvoda Evaluator Baurzhan Zhussupov Evaluator Jamila Asanova 1 https://www.un.org/Depts/Cartographic/map/profile/kazakhst.pdf ii EVALUATION REPORT: The 3rd and 4th UNFPA Country Programmes for Kazakhstan (2010-2018) Acknowledgements The authors wish to acknowledge with their sincere thanks the numerous staff members from the various Government of Kazakhstan Ministries and related institutions, the UN collaborating agencies, donor agencies and a wide range of CSOs for providing time, resources and materials to permit the development and implementation of this evaluation. We appreciate the participation of members of the Evaluation Reference Group, especially those who took time to attend briefings and provided comments. We are particularly grateful to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kazakhstan staff members of country and regional offices who, despite a very heavy load of other pressing commitments, were so responsive to our repeated requests, often on short notice. We would also like to acknowledge the many other Kazakh stakeholders and client/beneficiaries, including experts in P&D, health, youth, gender and the dedicated staff at the visited centers, who helped the implementation of this evaluation despite their busy schedules. It is the team's hope that this evaluation and recommendations presented in this report will positively contribute to building a sound foundation for future UNFPA Kazakhstan supported programs in collaboration with the Government of Kazakhstan.