Five Centuries of Medical Contributions from the Royal Navy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conference and Dinner Venue Hire Historic

CONFERENCE AND DINNER VENUE HIRE HISTORIC . UNIQUE . ICONIC The National Museum of the Royal Navy The National Museum of the Royal Navy Venues A2047 Explosion! Museum of Naval Firepower LANDPORT Priddys Hard, Gosport, A2047 PO12 4LE PORTSEA ISLAND BUCKLAND The National Museum FRATTON of the Royal Navy HM Naval Base (PP66), A3 Portsmouth, PO1 3NH HM NAVAL BASE A2030 HMS Warrior HMS Victory A2047 Victory Gate, HM Naval HM Naval Base Base, Portsmouth, (PP66), Portsmouth, MILTON PO1 3QX PO1 3NH A3 A32 PORTSEA GUNWHARF A2030 A2030 GOSPORT B3333 QUAYS A3 The Royal Navy Submarine Museum Haslar Jetty, Gosport, PO12 2AS Royal Marines Museum A288 Eastney Esplanade, Southsea, PO4EASTNEY 9PX A2154 A2154 A288 A288 SOUTHSEA Welcome to the National Museum of the Royal Navy The National Museum of the Royal Navy group tells the story of the Royal Navy from the earliest times to the present day. This is a crucial story; in many important ways the Royal Navy shaped the modern world. With an abundance of atmosphere and history, we offer a unique collection of venues that is unparalleled in Hampshire. The National Museum of the Royal Navy has already invested heavily in the careful and sympathetic restoration of the group’s historic ships and magnificent museums, with more to come. All profits from income generated through hiring of our rooms and facilities goes to support the conservation of naval heritage. Suitable for any event, our spaces range from quirky conference venues to unforgettable dinner locations. Our dedicated events teams will be available to offer advice and assistance from the first enquiry to the event itself. -

1 the Comets of Caroline Herschel (1750-1848)

Inspiration of Astronomical Phenomena, INSAP7, Bath, 2010 (www.insap.org) 1 publication: Culture and Cosmos, Vol. 16, nos. 1 and 2, 2012 The Comets of Caroline Herschel (1750-1848), Sleuth of the Skies at Slough Roberta J. M. Olson1 and Jay M. Pasachoff2 1The New-York Historical Society, New York, NY, USA 2Hopkins Observatory, Williams College, Williamstown, MA, USA Abstract. In this paper, we discuss the work on comets of Caroline Herschel, the first female comet-hunter. After leaving Bath for the environs of Windsor Castle and eventually Slough, she discovered at least eight comets, five of which were reported in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. We consider her public image, astronomers' perceptions of her contributions, and the style of her astronomical drawings that changed with the technological developments in astronomical illustration. 1. General Introduction and the Herschels at Bath Building on the research of Michael Hoskini and our book on comets and meteors in British art,ii we examine the comets of Caroline Herschel (1750-1848), the first female comet-hunter and the first salaried female astronomer (Figure 1), who was more famous for her work on nebulae. She and her brother William revolutionized the conception of the universe from a Newtonian one—i.e., mechanical with God as the great clockmaker watching over its movements—to a more modern view—i.e., evolutionary. Figure 1. Silhouette of Caroline Herschel, c. 1768, MS. Gunther 36, fol. 146r © By permission of the Oxford University Museum of the History of Science Inspiration of Astronomical Phenomena, INSAP7, Bath, 2010 (www.insap.org) 2 publication: Culture and Cosmos, Vol. -

Encountering Oceania: Bodies, Health and Disease, 1768-1846

Encountering Oceania: Bodies, Health and Disease, 1768-1846. Duncan James Robertson PhD University of York English July 2017 Duncan Robertson Encountering Oceania Abstract This thesis offers a critical re-evaluation of representations of bodies, health and disease across almost a century of European and North American colonial encounters in Oceania, from the late eighteenth-century voyages of James Cook and William Bligh, to the settlement of Australia, to the largely fictional prose of Herman Melville’s Typee. Guided by a contemporary and cross-disciplinary analytical framework, it assesses a variety of media including exploratory journals, print culture, and imaginative prose to trace a narrative trajectory of Oceania from a site which offered salvation to sickly sailors to one which threatened prospective settlers with disease. This research offers new contributions to Pacific studies and medical history by examining how late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century concepts of health and disease challenged, shaped and undermined colonial expansion in Oceania from 1768-1846. In particular, it aims to reassess the relationship between contemporary thinking on bodies, health and disease, and the process of colonial exploration and settlement in the period studied. It argues that this relationship was less schematic than some earlier scholarship has allowed, and adopts narrative medical humanities approaches to consider how disease and ill-health was perceived from individual as well as institutional perspectives. Finally, this thesis analyses representations of bodies, health and disease in the period from 1768-1846 in two ways. First, by tracing the passage of disease from ship to shore and second, by assessing the legacy of James Cook’s three Pacific voyages on subsequent phases of exploration and settlement in Oceania. -

Solent News the Newsletter of the Solent Forum Issue 43: Winter 2017/18

Solent News The newsletter of the Solent Forum Issue 43: Winter 2017/18 Inside this issue... • Latest news from the Solent Forum • Great British Beach Clean • Microbead plastic ban • 2017 Bathing Water results • New fishing byelaws • New good practice guidance for marine aggregates • Managing marine recreational activities in Marine Protected Areas • Saltmarsh recharge at Lymington Harbour • Waders and brent goose strategy update Beneficial Use of Dredge Sediment in the Solent (BUDS) • Green Halo project launch During the course of 2017, the Solent Forum progressed Phase 1 of the ‘Beneficial Use of Environmentally friendly • Dredge Sediment in the Solent’ (BUDS) project. This showed that around one million cubic moorings workshop metres of fine sediment is typically excavated each year in the area; however, no more • The Blue Belt Programme than 0.02 percent of this (at best) is used beneficially to protect and restore its deteriorating • Solent Oyster marshes and coastline. Regeneration project update Phase 1 of the project is being undertaken by ABPmer (who have also contributed to the initiative from their own research budget) and is being overseen by a specialist technical • Southern Water tackles misconnections group. The project team have undertaken the following tasks: • The Year of the Pier • A brief introductory literature review to provide a context for the investigation and review the • Haslar Barracks challenges, identify other contemporary initiatives and describe proven case examples. development • A specific investigation into the costs and benefits of using sediment to restore habitats • Ferry travel art inspiration in order to inform discussions about the objectives of, and funding streams for, future projects. -

The Royal Hospital Haslar: from Lind to the 21St Century

36 General History The Royal Hospital Haslar: from Lind to the 21st century E Birbeck In 1753, the year his Treatise of the Scurvy was published (1,2), The original hospital plans included a chapel within the James Lind was invited to become the Chief Physician of the main hospital, which was to have been sited in the fourth Royal Hospital Haslar, then only partially built. However, he side of the quadrangular building. Due to over-expenditure, declined the offer and George Cuthbert took the post. this part of the hospital was never built. St. Luke’s Church A few years later the invitation to Lind was repeated. On was eventually built facing the quadrangle. Construction of this occasion Lind accepted, and took up the appointment the main hospital building eventually stopped in 1762. in 1758. In a letter sent that year to Sir Alexander Dick, a friend who was President of the Royal College of Physicians Early administration of Haslar Edinburgh, Lind referred to Haslar hospital as ‘an immense Responsibility for the day to day running of the hospital lay pile of building & … will certainly be the largest hospital in with Mr Richard Porter, the Surgeon and Agent for Gosport Europe when finished…’ (3). The year after his appointment, (a physician who was paid by the Admiralty to review and reflecting his observations on the treatment of scurvy, Lind care for sailors of the Fleet for a stipend from the Admiralty), is reputed to have advised Sir Edward Hawke, who was who had had to cope with almost insurmountable problems. -

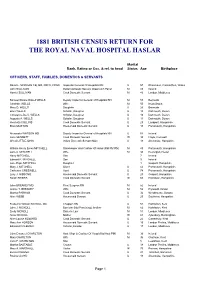

Haslar Census 1881

1881 BRITISH CENSUS RETURN FOR THE ROYAL NAVAL HOSPITAL HASLAR Marital Rank, Rating or Occ. & rel. to head Status Age Birthplace OFFICERS, STAFF, FAMILIES, DOMESTICS & SERVANTS David L. MORGAN CB, MD, FRCS, FRGS Inspector General Of Hospitals RN U 57 Rhosmaen, Carmarthen, Wales John SULLIVAN Butler Domestic Servant Greenwich Pensr M 43 Ireland Harriet SULLIVAN Cook Domestic Servant M 40 London, Middlesex Samuel Sloane Dalzell WELLS Deputy Inspector General of Hospitals RN M 57 Bermuda Charlotte WELLS Wife M 50 Nova Scotia Mary D. WELLS Daughter U 26 Bermuda Ellen WELLS Scholar, Daughter U 15 Dartmouth, Devon Constance De V. WELLS Scholar, Daughter U 13 Dartmouth, Devon Augusta A. WELLS Scholar, Daughter U 11 Dartmouth, Devon Henrietta COLLINS Cook Domestic Servant U 23 Landport, Hampshire Ellen MUSTON Housemaid Domestic Servant U 18 Portsmouth, Hampshire Alexander WATSON MD Deputy Inspector General of Hospitals RN U 54 Ireland Jane SENNETT Cook Domestic Servant W 34 Hayle, Cornwall Alfred LITTLEJOHN Indoor Domestic Servant Male U 18 Alverstoke, Hampshire William Henry Emes MITCHELL Storekeeper And Cashier Of Hospl (Rtd PM RN) M 40 Portsmouth, Hampshire Jane A. MITCHELL Wife M 33 Devonport, Devon Harry MITCHELL Son 7 Ireland Edward P. MITCHELL Son 3 Ireland Jane Hope MITCHELL Daughter 1 Gosport, Hampshire Mary J. MITCHELL Sister U 42 Portsmouth, Hampshire Catherine CRESWELL Aunt U 74 Portsmouth, Hampshire Lucy J. GIBBONS Housemaid Domestic Servant U 20 Gosport, Hampshire Sarah SHIERS Cook Domestic Servant W 65 Horndean, Hampshire John BREAKEY MD Fleet Surgeon RN M 52 Ireland Jeanie T. BREAKEY Wife M 52 Plymouth, Devon Martha PARHAM Cook Domestic Servant U 32 Westbourne, Sussex Alice WEBB Housemaid Servant U 20 Southsea, Hampshire Frederick William NICKOLL MA Chaplain RN U 54 Harbledon, Kent John J. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

North Atlantic Press Gangs: Impressment and Naval-Civilian Relations in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, 1749-1815 by Keith Mercer Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia August 2008 © Copyright by Keith Mercer, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43931-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43931-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Founding Fellows

Founding Members of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Alexander Abercromby, Lord Abercromby William Alexander John Amyatt James Anderson John Anderson Thomas Anderson Archibald Arthur William Macleod Bannatyne, formerly Macleod, Lord Bannatyne William Barron (or Baron) James Beattie Giovanni Battista Beccaria Benjamin Bell of Hunthill Joseph Black Hugh Blair James Hunter Blair (until 1777, Hunter), Robert Blair, Lord Avontoun Gilbert Blane of Blanefield Auguste Denis Fougeroux de Bondaroy Ebenezer Brownrigg John Bruce of Grangehill and Falkland Robert Bruce of Kennet, Lord Kennet Patrick Brydone James Byres of Tonley George Campbell John Fletcher- Campbell (until 1779 Fletcher) John Campbell of Stonefield, Lord Stonefield Ilay Campbell, Lord Succoth Petrus Camper Giovanni Battista Carburi Alexander Carlyle John Chalmers William Chalmers John Clerk of Eldin John Clerk of Pennycuik John Cook of Newburn Patrick Copland William Craig, Lord Craig Lorentz Florenz Frederick Von Crell Andrew Crosbie of Holm Henry Cullen William Cullen Robert Cullen, Lord Cullen Alexander Cumming Patrick Cumming (Cumin) John Dalrymple of Cousland and Cranstoun, or Dalrymple Hamilton MacGill Andrew Dalzel (Dalziel) John Davidson of Stewartfield and Haltree Alexander Dick of Prestonfield Alexander Donaldson James Dunbar Andrew Duncan Robert Dundas of Arniston Robert Dundas, Lord Arniston Henry Dundas, Viscount Melville James Edgar James Edmonstone of Newton David Erskine Adam Ferguson James Ferguson of Pitfour Adam Fergusson of Kilkerran George Fergusson, Lord Hermand -

Windmills in Hampshire and the Isle of Wight —A Revised List of Sites

Proc. Hants Field dub Archaeol. Soc. 34, 1978, 53-57. WINDMILLS IN HAMPSHIRE AND THE ISLE OF WIGHT —A REVISED LIST OF SITES By J. R. KEN YON INTRODUCTION Europe at the beginning of the fifteenth cen WINDMILLS were to be found in Hampshire tury, and the earliest extant example in this from the middle ages onwards, their number country is at Burton Dassett, Warwickshire, being greater than there is visual evidence for which was built towards the end of the today. The first article on Hampshire's mills fifteenth century. The post mill survived at was by A. Keeble Shaw (1960). The gazetteer least until the late eighteenth century in of mills published by Ellis (1968) listed a total Hampshire, and the only tower mills that are of 170 mills still in existence, of which only still standing are all nineteenth century. five were windmills. The three inland sites There are two sites in Hampshire which of Chalton, Grateley and Bursledon are brick had windmills from the middle ages through built, whilst stone was used for those at to the nineteenth century, although no doubt Portchester and Langstone. A brick and flint many times rebuilt. These sites are Windmill tower mill at West Meon, later converted Hill, Chalton, and the Lumps Fort area, east into a dovecote, was omitted from the gazet of Southsea Castle. The Chalton mill, the teer although it is marked on an Ordnance only one to be depicted on Speed's map of Survey 6 in. map. The Isle of Wight was 1611, is first mentioned in 1289 (Page 1908, excluded from the survey. -

Sailors' Scurvy Before and After James Lind – a Reassessment

Historical Perspective Sailors' scurvy before and after James Lind–areassessment Jeremy Hugh Baron Scurvy is a thousand-year-old stereotypical disease characterized by apathy, weakness, easy bruising with tiny or large skin hemorrhages, friable bleeding gums, and swollen legs. Untreated patients may die. In the last five centuries sailors and some ships' doctors used oranges and lemons to cure and prevent scurvy, yet university-trained European physicians with no experience of either the disease or its cure by citrus fruits persisted in reviews of the extensive but conflicting literature. In the 20th century scurvy was shown to be due to a deficiency of the essential food factor ascorbic acid. This vitamin C was synthesized, and in adequate quantities it completely prevents and completely cures the disease, which is now rare. The protagonist of this medical history was James Lind. His report of a prospective controlled therapeutic trial in 1747 preceded by a half-century the British Navy's prevention and cure of scurvy by citrus fruits. After lime-juice was unwittingly substituted for lemon juice in about 1860, the disease returned, especially among sailors on polar explorations. In recent decades revisionist historians have challenged normative accounts, including that of scurvy, and the historicity of Lind's trial. It is therefore timely to reassess systematically the strengths and weaknesses of the canonical saga.nure_205 315..332 © 2009 International Life Sciences Institute INTRODUCTION patients do not appear on the ship’s sick list, his choice of remedies was improper, and his inspissated juice was Long intercontinental voyages began in the late 16th useless.“Scurvy” was dismissed as a catch-all term, and its century and were associated with scurvy that seamen dis- morbidity and mortality were said to have been exagger- covered could be cured and prevented by oranges and ated. -

SHOVELL and the LONGITUDE How the Death of Crayford’S Famous Admiral Shaped the Modern World

SHOVELL AND THE LONGITUDE How the death of Crayford’s famous admiral shaped the modern world Written by Peter Daniel With Illustrations by Michael Foreman Contents 1 A Forgotten Hero 15 Ships Boy 21 South American Adventure 27 Midshipman Shovell 33 Fame at Tripoli 39 Captain 42 The Glorious Revolution 44 Gunnery on the Edgar 48 William of Orange and the Troubles of Northern Ireland 53 Cape Barfleur The Five Days Battle 19-23 May 1692 56 Shovell comes to Crayford 60 A Favourite of Queen Anne 65 Rear Admiral of England 67 The Wreck of the Association 74 Timeline: Sir Cloudsley Shovell 76 The Longitude Problem 78 The Lunar Distance Method 79 The Timekeeper Method 86 The Discovery of the Association Wreck 90 Education Activities 91 Writing a Newspaper Article 96 Design a Coat of Arms 99 Latitude & Longitude 102 Playwriting www.shovell1714.crayfordhistory.co.uk Introduction July 8th 2014 marks the tercentenary of the Longitude Act (1714) that established a prize for whoever could identify an accurate method for sailors to calculate their longitude. Crayford Town Archive thus have a wonderful opportunity to tell the story of Sir Cloudesley Shovell, Lord of the Manor of Crayford and Rear Admiral of England, whose death aboard his flagship Association in 1707 instigated this act. Shovell, of humble birth, entered the navy as a boy (1662) and came to national prominence in the wars against the Barbary pirates. Detested by Pepys, hated by James II, Shovell became the finest seaman of Queen Anne’s age. In 1695 he moved to Crayford after becoming the local M.P. -

ROYAL NAVAL HOSPITAL, HASLAR Journals of Naval Surgeons, 1848

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT ROYAL NAVAL HOSPITAL, HASLAR Journals of naval surgeons, 1848-80 Reels M708-12 Library Royal Naval Hospital Haslar Road Gosport, Hampshire PO12 National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1967 HISTORICAL NOTE The Royal Hospital at Haslar, on the southern tip of Gosport Peninsula in Hampshire, was opened in 1754. At the time, it was the largest hospital in England and the largest brick building in Europe. By 1790 there were 2100 patients in the buildings. Until the twentieth century, the hospital was managed by naval officers rather than doctors. However, the staff included some distinguished doctors. James Lind, who was Chief Physician from 1758 to 1783, was the author of A treatise of the scurvy (1753) in which he stressed the importance of fresh fruit and vegetables. The noted explorer and naturalist Sir John Richardson was Inspector of Hospitals and Fleets at Haslar from 1838 to 1855. Thomas Huxley worked at Haslar before joining HMS Rattlesnake in 1846. During World War I and World War II, the Royal Naval Hospital treated huge numbers of Allied and enemy troops. It remained an active hospital until the end of the twentieth century, finally closing in 2009. SURGEONS’ JOURNALS The journals of naval surgeons held in the library at the Royal Naval Hospital at Haslar were later transferred to the Public Record Office in London (now The National Archives). They were placed in Adm. 101. Admiralty, Medical departments, Registers and journals. In the following list, the current location of a journal within Adm. 101 is indicated at the end of each entry.