Contemporary Jazz Musicians' Work At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

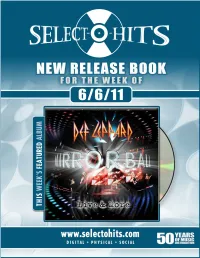

Soh6.6.11Newreleaseb

RETURNS WITH A THREE LP COLLECTION! MMMIIIRRRRRROOORRR BBBAAALLLLLL::: LLLIIIVVVEEE &&& MMMOOORRREEE This is the ULTIMATE live set! All of Def Leppard’s hits, recorded live for the first time ever, are on this 180 gram virgin vinyl, 3 LP collection. FOUR NEW SONGS ARE FEATURED, INCLUDING “UNDEFEATED,” THE CURRENT #1 SINGLE AT CLASSIC ROCK RADIO. TITLE: MIRROR BALL ‐ LIVE & MORE RELEASE DATE: 7/5/11 LABEL: MAILBOAT RECORDS UPC: 698268952003 CATALOG #: MBR 9520 CLICK HERE TO LISTEN TO THE #1 SONG “UNDEFEATED” LP 1 LP 3 Rock! Rock (‘Til You Drop) Rock of Ages SUMMER TOUR DATES WITH SPECIAL GUEST HEART Rocket Let’s Get Rocked Animal June 15 West Palm Beach, FL July 23 New Orleans, LA Bonus Live: June 17 Tampa, FL July 24 San Antonio, TX C’mon C’mon Action June 18 Atlanta, GA August 8 Sturgis, SD Make Love Like A Man Bad Actress June 19 Orange Beach, AL August 10 St. Louis, MO Too Late For Love Undefeated June 22 Charlotte, NC August 13 Des Moines, IA Foolin’ June 24 Raleigh, NC August 16 Toronto, CAN Kings of the World June 25 Virginia Beach, VA August 17 Detroit, MI Nine Lives New Songs: June 26 Philadelphia, PA August 19 Louisville, KY Love Bites Undefeated June 29 Scranton, PA August 20 Pittsburgh, PA Kings of the World June 30 Boston, MA August 21 Buffalo, NY July 2 Uncasville, CT August 24 Cleveland, OH LP 2 It’s All About Believin’ July 3 Hershey, PA August 26 St. Paul, MN Rock On July 5 Milwaukee, WI August 27 Kansas City, MO Two Steps Behind July 7 Cincinnati, OH August 29 Denver, CO Bringin’ on the Heartbreak July 9 Washington, DC -

George Harrison

COPYRIGHT 4th Estate An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020 Copyright © Craig Brown 2020 Cover design by Jack Smyth Cover image © Michael Ochs Archives/Handout/Getty Images Craig Brown asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008340001 Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008340025 Version: 2020-03-11 DEDICATION For Frances, Silas, Tallulah and Tom EPIGRAPHS In five-score summers! All new eyes, New minds, new modes, new fools, new wise; New woes to weep, new joys to prize; With nothing left of me and you In that live century’s vivid view Beyond a pinch of dust or two; A century which, if not sublime, Will show, I doubt not, at its prime, A scope above this blinkered time. From ‘1967’, by Thomas Hardy (written in 1867) ‘What a remarkable fifty years they -

Upcoming Events

Newsletter of the Sacramento Traditional Jazz Society STJS is a non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation and promotion of traditional jazz music. Address: 2521 Port Street, West Sacramento, CA 95691•(916)444-2004•www.sacjazz.org VOLUME49•NO.7 August 2017 Jazz Sunday, August 6 (FIRST Sunday!) Note from The President …..……...2 Week Two STJS Jazz Campers Concert and ElksLodge#6–info/directions ....... 2 The Professors The Professors …………………………..3 Raffle Cent$.................................8 Race for the Art Pictures…………….8 Membership Application…….……13 Upcoming Events: July 23-29 Week 1 STJS Teagarden EEachy E Youth Jazz Camp Each year when the jazz camps conclude, we are treated to a special July 29 Week 1 STJS Jazz Campers Concert and The Counselors Jazz Jazz Sunday that features not only The Professors both youth Band campers and counselors as well. August Jazz Sunday is one of the July 31–Aug 6 Week 2 - STJS best STJS events of the year. The place is buzzing with excitement Teagarden Youth Camp from a productive and fun-filled week at Jazz Camp amid the scenic Aug 6 (First Sun) Week 2 STJS Jazz beauty of Pollock Pines. Campers have been making new friends Campers Concert and The Professors while counselors (former campers) are having a blast reuniting with their musician friends. Sept 10 – Skin ‘n Bones (Gonsoulin) Oct 8 – Pub Crawlers Our Jazz Camp Faculty is loaded with all-star talent, and we are Nov 12 – Youth Jazz Day incredibly fortunate to have them all here together as our guest Dec 10 – Gold Society Jazz band. -

Pynchon's Sound of Music

Pynchon’s Sound of Music Christian Hänggi Pynchon’s Sound of Music DIAPHANES PUBLISHED WITH SUPPORT BY THE SWISS NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION 1ST EDITION ISBN 978-3-0358-0233-7 10.4472/9783035802337 DIESES WERK IST LIZENZIERT UNTER EINER CREATIVE COMMONS NAMENSNENNUNG 3.0 SCHWEIZ LIZENZ. LAYOUT AND PREPRESS: 2EDIT, ZURICH WWW.DIAPHANES.NET Contents Preface 7 Introduction 9 1 The Job of Sorting It All Out 17 A Brief Biography in Music 17 An Inventory of Pynchon’s Musical Techniques and Strategies 26 Pynchon on Record, Vol. 4 51 2 Lessons in Organology 53 The Harmonica 56 The Kazoo 79 The Saxophone 93 3 The Sounds of Societies to Come 121 The Age of Representation 127 The Age of Repetition 149 The Age of Composition 165 4 Analyzing the Pynchon Playlist 183 Conclusion 227 Appendix 231 Index of Musical Instruments 233 The Pynchon Playlist 239 Bibliography 289 Index of Musicians 309 Acknowledgments 315 Preface When I first read Gravity’s Rainbow, back in the days before I started to study literature more systematically, I noticed the nov- el’s many references to saxophones. Having played the instru- ment for, then, almost two decades, I thought that a novelist would not, could not, feature specialty instruments such as the C-melody sax if he did not play the horn himself. Once the saxophone had caught my attention, I noticed all sorts of uncommon references that seemed to confirm my hunch that Thomas Pynchon himself played the instrument: McClintic Sphere’s 4½ reed, the contra- bass sax of Against the Day, Gravity’s Rainbow’s Charlie Parker passage. -

Scripting and Consuming Black Bodies in Hip Hop Music and Pimp Movies

SCRIPTING AND CONSUMING BLACK BODIES IN HIP HOP MUSIC AND PIMP MOVIES Ronald L Jackson II and Sakile K. Camara ... Much of the assault on the soulfulness of African American people has come from a White patriarchal, capitalist-dominated music industry, which essentially uses, with their consent and collusion, Black bodies and voices to be messengers of doom and death. Gangsta rap lets us know Black life is worth nothing, that love does not exist among us, that no education for critical consciousness can save us if we are marked for death, that women's bodies are objects, to be used and discard ed. The tragedy is not that this music exists, that it makes a lot of money, but that there is no countercultural message that is equally powerful, that can capture the hearts and imaginations of young Black folks who want to live, and live soulfully) Feminist film critics maintain that the dominant look in cinema is, historically, a gendered gaze. More precisely, this viewpoint argues that the dominant visual and narrative conventions of filmmaking generally fix "women as image" and "men as bearer of the image." I would like to suggest that Hollywood cinema also frames a highly particularized racial gaze-that is, a representational system that posi tions Blacks as image and Whites as bearer of the image.2 Black bodies have become commodities in the mass media marketplace, particu larly within Hip Hop music and Black film. Within the epigraph above, both hooks and Watkins explain the debilitating effects that accompany pathologized fixations on race and gender in Black popular culture. -

Change Short Documentary Film Production Class

REEL CHANGE SHORT DOCUMENTARY FILM PRODUCTION CLASS LEARN FROM PROFESSIONAL FILM MAKERS WORKING IN THE FIELD. DATES AND TIMES EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES – Students will: MAY 12,19,26 | JUNE 2,9,16,23,30 • Understand how visual and aural information communicate a point of view JULY 7,14,21,28 • Utilize creative and structural thinking skills to write a story outline (9:30AM - 12:30PM) • Collaborate in teams and develop effective observation, listening, and interviewing skills • Use video and audio equipment technically and creatively TUITION & REGISTRATION • Create a compelling visual story using non-linear editing tools while applying organizational, technical, and creative skills to various elements of the film TUITION: $475 | SIBLING DISCOUNT: $445 (interviews, “b-roll”, music, sound effects, voice over, graphics) The class is suitable for adults and kids 14+ Lifelong Learning: In this extensive production course, students will have the Research shows that out-of-school programs enhance and complement students’ in-school opportunity to make a short film that expresses a point of experience, support healthy social and emotional development, foster cultural diversity, teach crucial 21st century skills, and promote academic success. view about local issues that resonate worldwide. Films can be personal or political, serious or funny. Documentary filmmaking is an art form that allows the filmmakers to work collaboratively and cultivate a unique voice that can be used in both academic settings and the real world, while making projects that positively impact the community. This hands-on course supports students’ engagement in their local community by teaching them the principles of merging Students will complete the course with a refined proficiency in the areas of critical thinking, problem solving, and communication, while also engaging in a creative outlet and telling everyday events and journalism with the art and skill of stories that they are passionate about. -

U.S. National Tour of the West End Smash Hit Musical To

Tweet it! You will always love this musical! @TheBodyguardUS comes to @KimmelCenter 2/21–26, based on the Oscar-nominated film & starring @Deborah_Cox Press Contacts: Amanda Conte [email protected] (215) 790-5847 Carole Morganti, CJM Public Relations [email protected] (609) 953-0570 U.S. NATIONAL TOUR OF THE WEST END SMASH HIT MUSICAL TO PLAY PHILADELPHIA’S ACADEMY OF MUSIC FEBRUARY 21–26, 2017 STARRING GRAMMY® AWARD NOMINEE AND R&B SUPERSTAR DEBORAH COX FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, December 22, 2016) –– The Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts and The Shubert Organization proudly announce the Broadway Philadelphia run of the hit musical The Bodyguard as part of the show’s first U.S. National tour. The Bodyguard will play the Kimmel Center’s Academy of Music from February 21–26, 2017 starring Grammy® Award-nominated and multi-platinum R&B/pop recording artist and film/TV actress Deborah Cox as Rachel Marron. In the role of bodyguard Frank Farmer is television star Judson Mills. “We are thrilled to welcome this new production to Philadelphia, especially for fans of the iconic film and soundtrack,” said Anne Ewers, President & CEO of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. “This award-winning stage adaption and the incomparable Deborah Cox will truly bring this beloved story to life on the Academy of Music stage.” Based on Lawrence Kasdan’s 1992 Oscar-nominated Warner Bros. film, and adapted by Academy Award- winner (Birdman) Alexander Dinelaris, The Bodyguard had its world premiere on December 5, 2012 at London’s Adelphi Theatre. The Bodyguard was nominated for four Laurence Olivier Awards including Best New Musical and Best Set Design and won Best New Musical at the WhatsOnStage Awards. -

A Singer Who Let That Big Light of Hers Shine by Dwight Garner Odetta Performing on Stage in London in 1963

A Singer Who Let That Big Light of Hers Shine By Dwight Garner Odetta performing on stage in London in 1963. Ronald Dumont/Hulton Archive, via Getty Images In the biography of nearly every white rock performer of a certain vintage, there’s a pivotal moment — more pivotal than signing the ill-advised first contract that leads to decades of litigation, and more pivotal than the first social disease. The moment is when the subject watched Elvis Presley’s appearance on “The Ed Sullivan Show” on Sept. 9, 1956. For Black audiences and many future musicians, the crucial moment came three years later. On Dec. 10, 1959, CBS, in partnership with Revlon, broadcast a prime-time special called “Tonight With Belafonte,” produced and hosted by Harry Belafonte, the debonair and rawboned Jamaican- American singer. These weren’t easy years for Black families to gather around the television. As Margo Jefferson wrote in her memoir “Negroland,” they turned on the set “waiting to be entertained and hoping not to be denigrated.” Belafonte was given artistic control over his program. He told executives he wanted a largely unknown folk singer named Odetta to perform prominently. One executive asked, “Excuse me, Harry, but what is an Odetta?” Revlon was bemused to learn she did not wear makeup. The hourlong show was commercial-free except for a Revlon spot at the beginning and end. At the start, Belafonte sang two songs. In what is, amazingly, the first in-depth biography of this performer, “Odetta: A Life in Music and Protest,” the music writer Ian Zack picks up the story. -

Reading in the Dark: Using Film As a Tool in the English Classroom. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 456 446 CS 217 685 AUTHOR Golden, John TITLE Reading in the Dark: Using Film as a Tool in the English Classroom. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-3872-1 PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 199p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 38721-1659: $19.95, members; $26.95, nonmembers). Tel: 800-369-6283 (Toll Free); Web site http://www.ncte.org. PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Classroom Techniques; *Critical Viewing; *English Instruction; *Film Study; *Films; High Schools; Instructional Effectiveness; Language Arts; *Reading Strategies; Units of Study IDENTIFIERS *Film Viewing; *Textual Analysis ABSTRACT To believe that students are not using reading and analytical skills when they watch or "read" a movie is to miss the power and complexities of film--and of students' viewing processes. This book encourages teachers to harness students' interest in film to help them engage critically with a range of media, including visual and printed texts. Toward this end, the book provides a practical guide to enabling teachers to ,feel comfortable and confident about using film in new and different ways. It addresses film as a compelling medium in itself by using examples from more than 30 films to explain key terminology and cinematic effects. And it then makes direct links between film and literary study by addressing "reading strategies" (e.g., predicting, responding, questioning, and storyboarding) and key aspects of "textual analysis" (e.g., characterization, point of view, irony, and connections between directorial and authorial choices) .The book concludes with classroom-tested suggestions for putting it all together in teaching units on 11 films ranging from "Elizabeth" to "Crooklyn" to "Smoke Signals." Some other films examined are "E.T.," "Life Is Beautiful," "Rocky," "The Lion King," and "Frankenstein." (Contains 35 figures. -

SCMS 2019 Conference Program

CELEBRATING SIXTY YEARS SCMS 1959-2019 SCMSCONFERENCE 2019PROGRAM Sheraton Grand Seattle MARCH 13–17 Letter from the President Dear 2019 Conference Attendees, This year marks the 60th anniversary of the Society for Cinema and Media Studies. Formed in 1959, the first national meeting of what was then called the Society of Cinematologists was held at the New York University Faculty Club in April 1960. The two-day national meeting consisted of a business meeting where they discussed their hope to have a journal; a panel on sources, with a discussion of “off-beat films” and the problem of renters returning mutilated copies of Battleship Potemkin; and a luncheon, including Erwin Panofsky, Parker Tyler, Dwight MacDonald and Siegfried Kracauer among the 29 people present. What a start! The Society has grown tremendously since that first meeting. We changed our name to the Society for Cinema Studies in 1969, and then added Media to become SCMS in 2002. From 29 people at the first meeting, we now have approximately 3000 members in 38 nations. The conference has 423 panels, roundtables and workshops and 23 seminars across five-days. In 1960, total expenses for the society were listed as $71.32. Now, they are over $800,000 annually. And our journal, first established in 1961, then renamed Cinema Journal in 1966, was renamed again in October 2018 to become JCMS: The Journal of Cinema and Media Studies. This conference shows the range and breadth of what is now considered “cinematology,” with panels and awards on diverse topics that encompass game studies, podcasts, animation, reality TV, sports media, contemporary film, and early cinema; and approaches that include affect studies, eco-criticism, archival research, critical race studies, and queer theory, among others. -

Neuhoff, Laura-Brynn.Pdf (929Kb)

“THE BIGGEST COLORED SHOW ON EARTH”: HOW MINSTRELSY HAS DEFINED PERFORMANCES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN IDENTITY FROM 19TH CENTURY THEATER TO HIP HOP A Senior Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in American Studies By Laura-Brynn Neuhoff Washington, D.C. April 26, 2017 “THE BIGGEST COLORED SHOW ONE EARTH”: HOW MINSTRELSY HAS DEFINED PERFORMANCES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN IDENTITY FROM 19TH CENTURY THEATER TO HIP HOP Laura-Brynn Neuhoff Thesis Adviser: Marcia Chatelain, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This senior thesis seeks to answer the following question: how and why is the word “minstrel” and associated images still used in American rap and hip hop performances? The question was sparked by the title of a 2005 rap album by the group Little Brother: The Minstrel Show. The record is packaged as a television variety show, complete with characters, skits, and references to blackface. This album premiered in the heat of the Minstrel Show Debate when questions of authenticity and representation in rap and hip hop engaged community members. My research is first historical: I analyze images of minstrelsy and reviews of minstrel shows from the 1840s into the twentieth century to understand how the racist images persisted and to unpack the ambiguity of the legacy of black blackface performers. I then analyze the rap scene from the late 2000-2005, when the genre most poignantly faced the identity crisis spurred by those referred to as “minstrel” performers. Having conducted interviews with the two lyricists of Little Brother: Rapper Big Pooh and Phonte, I primarily use Little Brother as my center of research, analyzing their production in conjunction with their spatial position in the hip hop community. -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter