1. Muritala.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

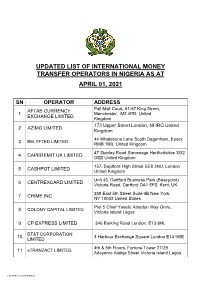

Updated List of International Money Transfer Operators in Nigeria As At

UPDATED LIST OF INTERNATIONAL MONEY TRANSFER OPERATORS IN NIGERIA AS AT APRIL 01, 2021 SN OPERATOR ADDRESS AFTAB CURRENCY Pall Mall Court, 61-67 King Street, 1 Manchester, M2 4PD, United EXCHANGE LIMITED Kingdom 173 Upper Street London, NI IRG United 2 AZIMO LIMITED Kingdom 44 Whalebone Lane South Dagenham, Essex 3 BELYFTED LIMITED RMB 1BB, United Kingdom 47 Stanley Road Stevenage Hertfordshire SG2 4 CAPEREMIT UK LIMITED OEE United Kingdom 157, Deptford High Street SE8 3NU, London 5 CASHPOT LIMITED United Kingdom Unit 46, Dartford Business Park (Basepoint) 6 CENTREXCARD LIMITED Victoria Road, Dartford DA1 5FS, Kent, UK 239 East 5th Street Suite 4B New York, 7 CHIME INC. NY 10003 United States Plot 5 Chief Yesefu Abiodun Way Oniru, 8 COLONY CAPITAL LIMITED Victoria Island Lagos 9 CP EXPRESS LIMITED 346 Barking Road London, E13 8HL DT&T CORPORATION 10 3 Harbour Exchange Square London E14 9GE LIMITED 4th & 5th Floors, Fortune Tower 27/29 11 eTRANZACT LIMITED Adeyemo Alakija Street Victoria Island Lagos Classified as Confidential FIEM GROUP LLC DBA 1327, Empire Central Drive St. 110-6 Dallas 12 PING EXPRESS Texas 6492 Landover Road Suite A1 Landover 13 FIRST APPLE INC. MD20785 Cheverly, USA FLUTTERWAVE 14 TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS 8 Providence Street, Lekki Phase 1 Lagos LIMITED FORTIFIED FRONTS LIMITED 15 in Partnership with e-2-e PAY #15 Glover Road Ikoyi, Lagos LIMITED FUNDS & ELECTRONIC 16 No. 15, Cameron Road, Ikoyi, Lagos TRANSFER SOLUTION FUNTECH GLOBAL Clarendon House 125 Shenley Road 17 COMMUNICATIONS Borehamwood Heartshire WD6 1AG United LIMITED Kingdom GLOBAL CURRENCY 1280 Ashton Old Road Manchester, M11 1JJ 18 TRAVEL & TOURS LIMITED United Kingdom Rue des Colonies 56, 6th Floor-B1000 Brussels 19 HOMESEND S.C.R.L Belgium IDT PAYMENT SERVICES 20 520 Broad Street USA INC. -

Here Is a List of Assets Forfeited by Cecilia Ibru

HERE IS A LIST OF ASSETS FORFEITED BY CECILIA IBRU 1. Good Shepherd House, IPM Avenue , Opp Secretariat, Alausa, Ikeja, Lagos (registered in the name of Ogekpo Estate Managers) 2. Residential block with 19 apartments on 34, Bourdillon Road , Ikoyi (registered in the name of Dilivent International Limited). 3.20 Oyinkan Abayomi Street, Victoria Island (remainder of lease or tenancy upto 2017). 4. 57 Bourdillon Road , Ikoyi. 5. 5A George Street , Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited), 6. 5B George Street , Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 7. 4A Iru Close, Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 8. 4B Iru Close, Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 9. 16 Glover Road , Ikoyi (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 10. 35 Cooper Road , Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 11. Property situated at 3 Okotie-Eboh, SW Ikoyi. 12. 35B Isale Eko Avenue , Dolphin Estate, Ikoyi. 13. 38A Isale Eko Avenue , Dolphin Estate, Ikoyi (registered in the name of Meeky Enterprises Limited). 14. 38B Isale Eko Avenue , Dolphin Estate, Ikoyi (registered in the name of Aleksander Stankov). 15. Multiple storey multiple user block of flats under construction 1st Avenue , Banana Island , Ikoyi, Lagos , (with beneficial interest therein purchased from the developer Ibalex). 16. 226, Awolowo Road , Ikoyi, Lagos (registered in the name of Ogekpo Estate Managers). 17. 182, Awolowo Road , Ikoyi, Lagos , (registered in the name of Ogekpo Estate Managers). 18. 12-storey Tower on one hectare of land at Ozumba Mbadiwe Water Front, Victoria Island . -

Curriculum Vitae Fagbayi, Tawakalt Ajoke

CURRICULUM VITAE FAGBAYI, TAWAKALT AJOKE PERMANENT HOME ADDRESS 1, Omidiji street, Otto, Ebute-Metta, Lagos Nigeria TEL NO: 08094105289/0701151913 E-MAILS: [email protected] [email protected] FAGBAYI, T.A. Page 1 PERSONAL DATA FULL NAME: FAGBAYI, Tawakalt Ajoke PLACE AND DATE OF BIRTH: Ebute-Metta, Lagos, Nigeria 8th December, 1983 PERMANENT Home ADDRESS 1, Omidiji street, Otto, Ebute-Metta, Lagos, Nigeria. SEX: Female NATIONALITY Nigerian STATE/ LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA Lagos State/ Mainland LGA MARITAL STATUS: Single NUMBER OF CHILDREN: None POSTAL ADDRESS Departement of Cell Biology & Genetics, Fauclty of Science, University of Lagos, Akoka, Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria TEL NO: 08094105289/0701151913 E-MAILS: [email protected] [email protected] EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS: (with dates) POST SECONDARY Qualifications Dates University of Lagos, Akoka, Lagos Ph.D. Cell & Molecular Biology in-view • University of Lagos, Akoka Lagos. MSc. Cell Biology & Genetics 2009-2010 • University of Lagos, Akoka, Lagos BSc. Cell Biology & Genetics 2003-2007 Second Class, Upper Division SECONDARY • Grace High School, Gbagada, Lagos, WASC 1996-2001 FAGBAYI, T.A. Page 2 ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS University Degree Class (If any) Institution Date of Award B.Sc. Hons Cell Biology & Second Class upper University of Lagos, 2008 Genetics Division Akoka, Lagos, Nigeria. M. Sc. Cell Biology and ,, 2010 Genetics Ph.D. Cell & Molecular ,, In - view Biology STATEMENT OF EXPERIENCE: PAST WORK & TEACHING EXPERIENCE Employer Designation Date Nature of Duty Department of Cell Facilitator and December 2014 Actively involved in all aspects of workshop Biology and Genetics Organizer March 2015 planning, including workshop simulation, University of Lagos, CBG Molecular compilation and acquisition of workshop Workshop & DNA materials, as well as facilitation of some Basics Workshop topics and hands-on practicals during workshop. -

Nigerian Nationalism: a Case Study in Southern Nigeria, 1885-1939

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1972 Nigerian nationalism: a case study in southern Nigeria, 1885-1939 Bassey Edet Ekong Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the African Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ekong, Bassey Edet, "Nigerian nationalism: a case study in southern Nigeria, 1885-1939" (1972). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 956. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.956 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF' THE 'I'HESIS OF Bassey Edet Skc1::lg for the Master of Arts in History prt:;~'entE!o. 'May l8~ 1972. Title: Nigerian Nationalism: A Case Study In Southern Nigeria 1885-1939. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITIIEE: ranklln G. West Modern Nigeria is a creation of the Britiahl who be cause of economio interest, ignored the existing political, racial, historical, religious and language differences. Tbe task of developing a concept of nationalism from among suoh diverse elements who inhabit Nigeria and speak about 280 tribal languages was immense if not impossible. The tra.ditionalists did their best in opposing the Brltlsh who took away their privileges and traditional rl;hts, but tbeir policy did not countenance nationalism. The rise and growth of nationalism wa3 only po~ sible tbrough educs,ted Africans. -

(AWS) AUDIT REPORT Nigerian Bottling Company Limited

ALLIANCE FOR WATER STEWARDSHIP (AWS) AUDIT REPORT Based on AWS Standard Version 1.0 Nigerian Bottling Company Limited (Member of Coca Cola Hellenic Group) #1 Lateef Jakande Road, Agidingbe Ikeja, Lagos State Nigeria. Report Date: 23-08-2019 Report Version: 02.0 Prepared by: Control Union Certification Services Accra, Ghana. Project No.: 867406AWS-2019-07 AWS Reference No.: AWS-010-INT-CU-00-05-00010-0072 Nigerian Bottling Company Limited AWS Audit Report Contents 1. General Information ............................................................................................................................. 3 1.1. Client Details ................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2. Certification Details ....................................................................................................................... 3 2. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... 3 3. Scope of Assessment............................................................................................................................. 4 4. Description of the Catchment ............................................................................................................... 4 5. Summary on Stakeholder and shared Water Challenges ..................................................................... 7 6. Summary of the Assessment................................................................................................................ -

Foreign Exchange Auction No. 57/2003 of 30Th July, 2003 Foreign Exchange Auction Sales Result Applicant Name Form Bid Cumm

1 CENTRAL BANK OF NIGERIA, ABUJA TRADE AND EXCHANGE DEPARTMENT FOREIGN EXCHANGE AUCTION NO. 57/2003 OF 30TH JULY, 2003 FOREIGN EXCHANGE AUCTION SALES RESULT APPLICANT NAME FORM BID CUMM. BANK WEIGHTED S/N A. SUCCESSFUL BIDS M/A NO R/C NO. APPLICANT ADDRESS RATE AMOUNT AMOUNT PURPOSE NAME AVERAGE 1 O. COLLINS RESOURCES INT'L LTD. MF0422914 428959 NA 7 A LINE LOCK UP SHOP,ARIARIA INT. MARKET,ABA129.5000 2,816.88 2,816.88 LUGGAGE AND BAGS ACCESS 0.0048 2 NIGERIAN EMBROIDERY LACE MFG AA 1292082 1,992 PLOT B, BLK 1, ILUPEJU INDUSTRIAL ESTATE,129.0000 LAGOS 8,999.44 11,816.32 REMITTANCE OF INTEREST ON FOREIGN LOAN STAND. CHARTD. 0.0153 3 NIGERIAN SYNTHETIC FABRICS LTD AA 1292084 4447 PLOT B, BLOCK 1, ILUPEJU INDUSTRIAL EST.,129.0000 LAGOS. 8,999.44 20,815.76 REMITTANCE OF INTEREST ON FOREIGN LOAN STAND. CHARTD. 0.0153 4 RINO RESOURCES LIMITED MF 0532954 A0901322 1C MARKET STREET EBUTE -METTA LAGOS 128.5000 150,000.00 170,815.76 457 PIECES OF USED MOTORCYCLES ACB 0.2549 5 AJIBODE LINDA FOLUSHO AA0925980 A1845004 H3A CLOSE G, LSDPC, OGUDU, LAGOS 128.5000 5,000.00 175,815.76 UPKEEP MAINTENANCE ALLOWANCE AFRI 0.0085 6 AJIBODE LINDA FOLUSHO AA0925978 A1845004 H3A CLOSE G, LSDPC, OGUDU, LAGOS 128.5000 10,000.00 185,815.76 SCHOOL FEES AFRI 0.0170 7 BLACKHORSE PLASTIC INDUSTRIES MF0524518 17737 6, IBASSA EXPRESSWAY, LAGOS 128.5000 132,440.00 318,255.76 ARTIFICIAL RESINS AFRI 0.2250 8 OKPECHI GABRIEL OKPECHINTA AA0731447 A0750421 PCE-AGG, SHELL PETROLEUM DEV. -

Nigeria and the Death of Liberal England Palm Nuts and Prime Ministers, 1914-1916

Britain and the World Nigeria and the Death of Liberal England Palm Nuts and Prime Ministers, 1914-1916 PETER J. YEARWOOD Britain and the World Series Editors Martin Farr School of Historical Studies Newcastle University Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK Michelle D. Brock Department of History Washington and Lee University Lexington, VA, USA Eric G. E. Zuelow Department of History University of New England Biddeford, ME, USA Britain and the World is a series of books on ‘British world’ history. The editors invite book proposals from historians of all ranks on the ways in which Britain has interacted with other societies since the seventeenth century. The series is sponsored by the Britain and the World society. Britain and the World is made up of people from around the world who share a common interest in Britain, its history, and its impact on the wider world. The society serves to link the various intellectual commu- nities around the world that study Britain and its international infuence from the seventeenth century to the present. It explores the impact of Britain on the world through this book series, an annual conference, and the Britain and the World journal with Edinburgh University Press. Martin Farr ([email protected]) is the Chair of the British Scholar Society and General Editor for the Britain and the World book series. Michelle D. Brock ([email protected]) is Series Editor for titles focusing on the pre-1800 period and Eric G. E. Zuelow (ezuelow@une. edu) is Series Editor for titles covering the post-1800 period. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14795 Peter J. -

The Changing Residential Districts of Lagos: How the Past Has Created the Present and What Can Be Done About It

The Changing Residential Districts of Lagos: How the Past Has Created the Present and What Can Be Done about It Basirat Oyalowo, University of Lagos, Nigeria Timothy Nubi, University of Lagos, Nigeria Bose Okuntola, Lagos State University, Nigeria Olufemi Saibu, University of Lagos, Nigeria Oluwaseun Muraina, University of Lagos, Nigeria Olanrewaju Bakinson, Lagos State Lands Bureau, Nigeria The European Conference on Arts & Humanities 2019 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract The position of Lagos as Nigeria’s economic centre is entrenched in its colonial past. This legacy continues to influence its residential areas today. The research work provides an analysis of the complexity surrounding low-income residential areas of Lagos since 1960, based on the work of Professor Akin Mabogunje, who had surveyed 605 properties in 21 communities across Lagos. Based on existing housing amenities, he had classified them as high grade, medium grade, lower grade and low grade residential areas. This research asks: In terms of quality of neighbourhood amenities, to what extent has the character of these neighbourhoods changed from their 1960 low grade classification? This research is necessary because these communities represent the inner slums of Lagos, and in order to proffer solutions to inherent problems, it is important to understand how colonial land policies brought about the slum origins of these communities. Lessons for the future can then become clearer. The study is based on a mixed methods approach suitable for multidisciplinary inquires. Quantitative data is gathered through a survey of the communities; with findings from historical records and in-depth interviews with residents to provide the qualitative research. -

Environmental Impact Assessment of the Proposed Earthcare Compost Facility At

E2376 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF THE PROPOSED EARTHCARE COMPOST FACILITY AT Public Disclosure Authorized ODOGUNYAN FARM SETTLEMENT, IKORODU, LAGOS STATE. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized REVISED REPORT EarthCare Nigeria Limited, 16 – 24 Ikoyi Road, Public Disclosure Authorized Lagos. October, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENT TITLE DESCRIPTION PAGE CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1.0 Introduction 1 1.2 Project Location 7 1.3 Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Process 9 1.4 Legal and Administrative Framework 14 1.5 Other National Requirements 17 1.6 Lagos State Laws 19 1.7 International Guidelines and Conventions 20 1.8 Company Health Safety and Environmental Policy (H.S.E.) 22 CHAPTER TWO: PROJECT JUSTIFICATION 2.1 Need for the Project 23 2.2 Project Objectives and Value 24 2.3 Envisaged Sustainability 25 2.4 Project Alternatives 26 2.5 Site Alternatives 30 CHAPTER THREE: PROJECT / PROCESS DESCRIPTION 3.1 Project Site 32 3.2 Source of Raw Materials 34 3.3 EarthCare Composting Facility Process Flow 35 3.4: The Inoculants 39 3.5 Technical and General Specifications of Some Essential Pieces of Equipment 40 3.6: Material Balance 49 ii 3.7 The Compost 50 3.8: ENL’s Technical Partner 52 CHAPTER FOUR: DESCRIPTION OF BASELINE ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITION 4.1: General Study Approach including Methodology. 53 4.2: Climate and Meteorology of the Project Area 54 4.3: Ambient Air Quality 59 4.4: Geology 64 4.5: Physico-chemical and Microbial Water Characteristics 65 4.6: Soil in the Study Area 72 4.7: Geotechnics 75 4.8: Vegetation and -

Effective Solid Waste Management: a Solution to the Menace of Marine Litter in Coastal Communities of Lagos State, Nigeria

Vol. 13(3), pp. 104-116, March 2019 DOI: 10.5897/AJEST2018.2588 Article Number: A4D07C760128 ISSN: 1996-0786 Copyright ©2019 African Journal of Environmental Science and Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJEST Technology Full Length Research Paper Effective solid waste management: A solution to the menace of marine litter in coastal communities of Lagos State, Nigeria Nubi Afolasade T.1*, Nubi Olubunmi A.2, Laura Franco-Garcia3 and Oyediran, Laoye O.4 1Department of Works and Physical Planning, University of Lagos, Akoka, Lagos, Nigeria. 2Nigerian Institute for Oceanography and Marine Research, Lagos, Nigeria. 3Centre for Studies in Technology and Sustainable Development, University of Twente, Netherlands. 4Environmental Laboratories Limited, Lagos, Nigeria. Received 27 September, 2018; Accepted 29 November, 2018 Effective management of solid wastes is a goal that is yet to be achieved in many countries, even developed ones. In attempt to carry out a study on effective waste management system as a solution to the menace marine litters posed on coastal communities, three coastal areas in Lagos State Nigeria which are known for fishing, recreation, housing, and other various coastal activities were selected. Three groups of research questions were formulated based on the problem perception and impacts, actors and level of governance, and strategy and instrument; and each question was examined, and specific strategy was developed for necessary data gathering. This study was based on the observational -

Our Lagos History-Alimotu Pelewura Dz

Vestiges Biographical Sketch Series 2018 Sketch 1 Lagos Women in Colonial History: a biographical sketch of Alimotu Pelewura Halimat T. Somotan, Columbia University From the 1920s until her death in 1951, Alimotu Pelewura served as the president of Lagos Market Women Association (LMWA) and remained at the forefront of anti-colonial campaigns. In the February 24th 1947 issue, the editor of West African Pilot described Pelewura as the “mother of metropolitan Lagos.” She collaborated with Herbert Macaulay, a politician, and journalist to challenge colonial policies that were detrimental to women’s interests as well as those of the community of Lagos. Pelewura was born in Lagos in 1871. Her father was Abibu Pelewura, a trader and a Muslim, who helped to construct the Koranic Central Mosque in Lagos. Like her father, she was a devout Muslim and was later honored as the Lady President of the Koranic Muslim community on January 27, 1946. She adopted her mother’s work as a fishmonger, and by the end of 1900, she was well established in the fish-selling business. In the 1920s, she was elected as the Alaga (Chair-woman) of Araromi market. After Macaulay founded the Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP) in 1923, he sought an alliance with Pelewura. Inspired by Macaulay’s example, she created and led the LMWA, which was the central organization for all market women in Lagos. LMWA consisted of about 8,000 members during Pelewura’ administration. Before Southern Nigerian women gained the right to vote in the 1950s, shepromoted the NNDP’s objectives and helped to support the election of its male candidates to the Lagos Town Council and the Nigerian Legislative Council. -

Republicof Nigeria “Official, Gazette

- Republicof Nigeria “Official, Gazette No.77 ° LAGOS- 4th: August, 1966 Vol. 53 - CONTENTS ‘ Page , Page Movements of Officers 1502-9 Examination in Law, General Orders, Finan- 8 cial Instructions, Police Orders and Instruc- Probate Notice * 4509 — tions and Practical Police Work, December - & 1966 .. 1518 bee 1509 Appointment e499: of Notary Public > Loss of Local Purchase Orders . 1518-9 * Addition to the List of Notaries Public . 1509 _ Loss ofReceipt Voucher os 1519 5 - : . Application for Registration of Trade Unions 1510 {os of Last PayCertificate 1519 ~. Appointment of Directors of the Central: - Lossof Original Local Purchase Order soe y, 1519 ¢ Bank of Nigeria s .- no 1510 - ' Loss of Official Receipts 1519 - Revocation of the Appointment of Chief Saba co as a Memberofthé Committee of Chiefs 1510 Central Bank of Nigeria—Return of Assets - and Liabilities as at Close of Business on , . -4 ] Addendum—Law Officers in the Capital . sth July, 1966 me . 1519 ' Territory Le Tee ve 1510 tees PL. .1520-4 Notice of Removal from the Register of Vacancies 7 7 2 1524-31 Companies 1S1i : . Lands Requiredforthe Serviceof the National ; Board a Customs and Excise—Sale of 1531.2 Military Government 3 > 4511 gods . ee “ * Appointment of Licensed Buying Agents “oo. 1512 ° : Lagos Land Registry—First Registration of . INDEX TO LeGaL NOTICES IN SUPPLEMENT + Titles1 ere ee ett. 1512-18No,. * “Short Title Page. Afoigwe Rural Call Office—Openingof. © 1518 ~° 68 MilitaryAdministrator of the Capital . Territory (Delegation of Powers) Zike AvenuePostal Agency—Opening of 1518 Notice. 1966 .. B343 No. 77, Vol. 53 1502 OFFICIAL GAZETTE 5 Government. Notsce No. 1432 STAFF CHANGES ‘NEWW APPOINTMENTS AND OTHER 2 The following are nitified for general intormation :— NEW APPOINTMENTS Appointment Date of Date of Depariment Name -Ippointment Arrival Stenographer, Grade II 3-12-62 Administration Nnoromele, P.