GRADUATE Dryision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jenny Reddish1 Labrets: Piercing and Stretching on the Northwest Coast and in Amazonia

Jenny Reddish1 LABRETS: PIERCING AND STRETCHING ON THE NORTHWEST COAST AND IN AMAZONIA Abstract This article examines the practice of piercing and stretching the lip in order to accommodate a labret in two regions: the North American Northwest Coast (with historical examples from Tlingit groups) and lowland South America (utilizing ethnographic writings on Suya and Kayapo communities). Drawing on the recent ‘sensorial turn’ within anthropology, I suggest an approach which goes beyond considerations of the symbolism of body ornaments and analyses how the infliction of pain they involve can be manipulated to serve processes of social maturation and instil values such as the importance of flamboyant oratory. Labrets are seen here as efficacious devices for producing different kinds of social bodies. Keywords: body ornaments; Northwest Coast; Suya; Kayapo; Tlingit; sensorial anthropology. ADORNOS LABIALES: PERFORACIÓN Y ESTIRAMIENTO EN LA COSTA NOROESTE Y EN LA AMAZONIA Resumen Este artículo examina la práctica de perforar y estirar el labio con el fin de acomodar un adorno labial en dos regiones: la Costa Noroeste de Norteamérica (con ejemplos históricos de los grupos tlingit) y las tierras bajas de Suramérica (utilizando etnografías de los suya y kayapó). Con base en el reciente “giro sensorial” en antropología, se propone una aproximación que va más allá de las consideraciones simbólicas de los ornamentos corporales y analiza cómo el dolor causado por esos ornamentos puede ser manipulado para servir a procesos de maduración social e impartir valores tales como la importancia de la oratoria fastuosa. Los adornos labiales son vistos aquí como artefactos eficaces para producir diferentes clases de cuerpos sociales. -

Sex, Violence and the Body: the Erotics of Wounding

Sex, Violence and the Body The Erotics of Wounding Edited by Viv Burr and Jeff Hearn PPL-UK_SVB-Burr_FM.qxd 9/24/2008 2:33 PM Page i Sex, Violence and the Body PPL-UK_SVB-Burr_FM.qxd 9/24/2008 2:33 PM Page ii Also by Viv Burr AN INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIONISM GENDER AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY INVITATION TO PERSONAL CONSTRUCT PSYCHOLOGY (with Trevor W. Butt) THE PERSON IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY Also by Jeff Hearn BIRTH AND AFTERBIRTH: A Materialist Account ‘SEX’ AT ‘WORK’: The Power and Paradox of Organisation Sexuality (with Wendy Parkin) THE GENDER OF OPPRESSION: Men, Masculinity and the Critique of Marxism MEN, MASCULINITIES AND SOCIAL THEORY (co-editor with David Morgan) MEN IN THE PUBLIC EYE: The Construction and Deconstruction of Public Men and Public Patriarchies THE VIOLENCES OF MEN: How Men Talk about and How Agencies Respond to Men’s Violence to Women CONSUMING CULTURES: Power and Resistance (co-editor with Sasha Roseneil) TRANSFORMING POLITICS: Power and Resistance (co-editor with Paul Bagguley) GENDER, SEXUALITY AND VIOLENCE IN ORGANIZATIONS: The Unspoken Forces of Organization Violations (with Wendy Parkin) ENDING GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE: A Call for Global Action to Involve Men (with Harry Ferguson et al.) INFORMATION SOCIETY AND THE WORKPLACE: Spaces, Boundaries and Agency (co-editor with Tuula Heiskanen) GENDER AND ORGANISATIONS IN FLUX? (co-editor with Päivi Eriksson et al.) HANDBOOK OF STUDIES ON MEN AND MASCULINITIES (co-editor with Michael Kimmel and R. W. Connell) MEN AND MASCULINITIES IN EUROPE (with Keith Pringle et al.) -

Blood Rituals from Art to Murder

The Sacrificial Aesthetic: Blood Rituals from Art to Murder Dawn Perlmutter Department of Fine Arts Cheyney University of Pennsylvania Cheyney PA 19319-0200 [email protected] [Ed. note 2/2017: Many of the links in this article have become invalid and been removed] The concept of the “sacrificial esthetic” introduced in Eric Gans’s Chronicle No. 184 entitled “Sacrificing Culture” describes a situation in which aesthetic forms remain sacrificial but have evolved from a necessary feature of social organization to a psychological element of the human condition. Gans concludes that art’s sacrificial esthetic is essentially exhausted as a creative force and argues that the future lies with simulations, virtual realities in which the spectator plays a partially interactive role. His most significant claim is that “This end of the ability of the esthetic to discriminate between the sacrificial and the antisacrificial is not the end of art. On the contrary, it liberates the esthetic from the ethical end of justifying sacrifice.” The consequence of the liberation of the ethical justification of sacrifice is the main concern of this essay. Throughout the history of art we have encountered images of blood, from the representations of wounded animals in the cave paintings of Lascaux through century after century of brutal Biblical images, through history paintings depicting scenes of war, up through the many films of war, horror, and violence. Blood is now off the canvas, off the screen and sometimes literally in your face. It is no coincidence that this substance has intrigued artists throughout history. Blood is fascinating; it simultaneously represents purity and impurity, the sacred and the profane, life and death. -

Copyright Protection for Tattoos: Are Tattoos Copies? Michael C

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 90 | Issue 4 Article 12 5-2015 Copyright Protection for Tattoos: Are Tattoos Copies? Michael C. Minahan Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Intellectual Property Commons Recommended Citation Michael C. Minahan, Copyright Protection for Tattoos: Are Tattoos Copies?, 90 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1713 (2014). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol90/iss4/12 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Law Review at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\90-4\NDL412.txt unknown Seq: 1 11-MAY-15 13:41 COPYRIGHT PROTECTION FOR TATTOOS: ARE TATTOOS COPIES? Michael C. Minahan* You put a tattoo on yourself with the knowledge that this body is yours to have and enjoy while you’re here. You have fun with it, and nobody else can control (sup- posedly) what you do with it. —Don Ed Hardy1 INTRODUCTION The practice and ritual of tattooing human skin has existed in all parts of the world and in most cultures for thousands of years.2 The modern his- tory of tattooing in Western cultures can be traced to the voyages of Captain James Cook to the South Pacific, where sailors encountered various Polyne- sian tribes among which tattooing was, and remains today, an important cul- tural practice and spiritual ritual.3 When these sailors, many of whom had adorned their bodies with tattoos, returned to Europe, they ignited an inter- est in tattooing known as the “tattoo rage,” which spread through nineteenth- century Europe. -

Copyrighting Tattoos: Artist Vs. Client in the Battle of the (Waiver) Forms Brayndi L

Mitchell Hamline Law Review Volume 42 | Issue 1 Article 8 2016 Copyrighting Tattoos: Artist vs. Client in the Battle of the (Waiver) Forms Brayndi L. Grassi Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/mhlr Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Grassi, Brayndi L. (2016) "Copyrighting Tattoos: Artist vs. Client in the Battle of the (Waiver) Forms," Mitchell Hamline Law Review: Vol. 42: Iss. 1, Article 8. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/mhlr/vol42/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mitchell Hamline Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. Grassi: Copyrighting Tattoos: Artist vs. Client in the Battle of the (Wai 2 (Do Not Delete) 3/24/2016 7:52 PM COPYRIGHTING TATTOOS: ARTIST VS. CLIENT IN THE BATTLE OF THE (WAIVER) FORMS* Brayndi L. Grassi† I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 44 II. BRIEF HISTORY OF COPYRIGHT LAW IN NEW MEDIUMS ........... 46 III. FIRST INSTANCE OF COPYRIGHTS IN TATTOOS: REED V. NIKE, INC. ................................................................................. 47 IV. ARE TATTOOS COPYRIGHTABLE? ............................................. 48 A. Tattoos Meet All of the Requirements of the Copyright Act ...... 49 1. Originality .................................................................... 49 2. Authorship ................................................................... -

Spotted.Yankton.Net...Upload & Share Your Photos For

PAGE 10B PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 7, 2014 MONDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT NOVEMBER 10, 2014 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Arthur Å Arthur Å Wild Wild Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Antiques Roadshow Antiques Roadshow Ice Warriors -- USA Sled Hockey BBC Charlie Rose (N) (In Tavis Smi- The Mind Antiques Roadshow PBS (DVS) (DVS) Kratts Å Kratts Å Speaks Business Stereo) Å “Miami Beach” Å “Madison” Å The U.S. sled hockey team. (In World Stereo) Å ley (N) Å of a Chef “Miami Beach” Å KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report Stereo) Å (DVS) News Å KTIV $ 4 $ Queen Latifah Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent The Voice The artists perform. (N) Å The Blacklist (N) News 4 Tonight Show Seth Meyers Daly News 4 Extra (N) Hot Bench Hot Bench Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big The Voice “The Live Playoffs, Night 1” The art- The Blacklist Red and KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Seth Last Call KDLT (Off Air) NBC (N) Å (N) Å Judy (N) Judy (N) News Nightly News Bang ists perform. (N) (In Stereo Live) Å Berlin head to Moscow. News Å Starring Jimmy Fallon Meyers (N) (In Ste- With Car- News Å KDLT % 5 % Å Å (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory (N) Å (In Stereo) Å reo) Å son Daly KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. -

Download the .Pdf File to Keep

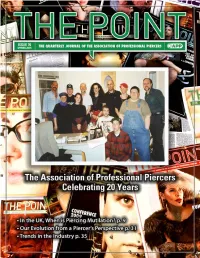

THE POINT THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF THE ASSOCIATION OF PROFESSIONAL PIERCERS BOARD OF DIRECTORS Brian Skellie—President Cody Vaughn—Vice-President Bethra Szumski—Secretary Paul King—Treasurer Christopher Glunt—Medical Liaison Ash Misako—Outreach Coordinator Miro Hernandez—Public Relations Director Steve Joyner—Legislation Liaison Jef Saunders—Membership Liaison ADMINISTRATOR Caitlin McDiarmid EDITORIAL STAFF Managing Editor of Design & Layout—Jim Ward Managing Editor of Content & Archives—Kendra Jane Berndt Managing Editor of Content & Statistics—Marina Pecorino Contributing Editor—Elayne Angel ADVERTISING [email protected] Front Cover: Back issues of The Point with a photo of the original APP founders. Their identities appear on page 20. ASSOCIATION OF PROFESSIONAL PIERCERS 1.888.888.1APP • safepiercing.org • [email protected] Donations to The Point are always appreciated. The Association of Professional Piercers is a California-based, interna- tional non-profit organization dedicated to the dissemination of vital health and safety information about body piercing to piercers, health care professionals, legislators, and the general public. Material submitted for publication is subject to editing. Submissions should be sent via email to [email protected]. The Point is not responsible for claims made by our advertisers. However, we reserve the right to reject advertising that is unsuitable for our publication. THE POINT ISSUE 70 3 FROM THE EDITORS INSIDE THIS ISSUE JIM WARD KENDRA BERNDT PRESIDENT’S CORNER–6 MARINA PECORINO The Point Editors IN THE UK, WHEN IS PIERCING MUTILATION?–9 Thank You Kim Zapata! THE APP BODY PIERCING ARCHIVE–17 n behalf of the Board, the readership, and the new editorial team we would like to sincerely thank Kimberly Zapata. -

Raymond & Leigh Danielle Austin

PRODUCT TRENDS, BUSINESS TIPS, NATIONAL TONGUE PIERCING DAY & INSTAGRAM FAVS Metal Mafia PIERCER SPOTLIGHT: RAYMOND & LEIGH DANIELLE AUSTIN of BODY JEWEL WITH 8 LOCATIONS ACROSS OHIO STATE Friday, August 14th is NATIONAL TONGUE PIERCING DAY! #nationaltonguepiercingday #nationalpiercingholidays #metalmafialove 14G Titanium Barbell W/ Semi Precious Stone Disc Internally Threaded Starting At $7.54 - TBRI14-CD Threadless Starting At $9.80 - TTBR14-CD 14G Titanium Barbell W/ Swarovski Gem Disc Internally Threaded Starting At $5.60 - TBRI14-GD Threadless Starting At $8.80 - TTBR14-GD @fallenangelokc @holepuncher213 Fallen Angel Tattoo & Body Piercing 14G Titanium Barbell W/ Dome Top 14G Titanium Barbell W/ Dome Top 14G ASTM F-67 Titanium Barbell Assortment Internally Threaded Starting At $5.46 - TBRI14-DM Internally Threaded Starting At $5.46 - TBRI14-DM Starting At $17.55 - ATBRE- Threadless Starting At $8.80 - TTBR14-DM Threadless Starting At $8.80 - TTBR14-DM 14G Threaded Barbell W Plain Balls 14G Steel Internally Threaded Barbell W Gem Balls Steel External Starting At $0.28 - SBRE14- 24 Piece Assortment Pack $58.00 - ASBRI145/85 Steel Internal Starting At $1.90 - SBRI14- @the.stabbing.russian Titanium Internal Starting At $5.40 - TBRI14- Read Street Tattoo Parlour ANODIZE ANY ASTM F-136 TITANIUM ITEM IN-HOUSE FOR JUST 30¢ EXTRA PER PIECE! Blue (BL) Bronze (BR) Blurple Dark Blue (DB) Dark Purple (DP) Golden (GO) Light Blue (LB) Light Purple (LP) Pink (PK) Purple (PR) Rosey Gold (RG) Yellow(YW) (Blue-Purple) (BP) 2 COPYRIGHT METAL MAFIA 2020 COPYRIGHT METAL MAFIA 2020 3 CONTENTS Septum Clickers 05 AUGUST METAL MAFIA One trend that's not leaving for sure is the septum piercing. -

Where's My Jet Pack?

Where's My Jet Pack? Online Communication Practices and Media Frames of the Emergent Voluntary Cyborg Subculture By Tamara Banbury A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Legal Studies Faculty of Public Affairs Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2019 Tamara Banbury Abstract Voluntary cyborgs embed technology into their bodies for purposes of enhancement or augmentation. These voluntary cyborgs gather in online forums and are negotiating the elements of subculture formation with varying degrees of success. The voluntary cyborg community is unusual in subculture studies due to the desire for mainstream acceptance and widespread adoption of their practices. How voluntary cyborg practices are framed in media articles can affect how cyborgian practices are viewed and ultimately, accepted or denied by those outside the voluntary cyborg subculture. Key Words: cyborg, subculture, implants, community, technology, subdermal, chips, media frames, online forums, voluntary ii Acknowledgements The process of researching and writing a thesis is not a solo endeavour, no matter how much it may feel that way at times. This thesis is no exception and if it weren’t for the advice, feedback, and support from a number of people, this thesis would still just be a dream and not a reality. I want to acknowledge the institutions and the people at those institutions who have helped fund my research over the last year — I was honoured to receive one of the coveted Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canada Graduate Scholarships for master’s students from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. -

The Atrocity Exhibition

The Atrocity Exhibition WITH AUTHOR'S ANNOTATIONS PUBLISHERS/EDITORS V. Vale and Andrea Juno BOOK DESIGN Andrea Juno PRODUCTION & PROOFREADING Elizabeth Amon, Laura Anders, Elizabeth Borowski, Curt Gardner, Mason Jones, Christine Sulewski CONSULTANT: Ken Werner Revised, expanded, annotated, illustrated edition. Copyright © 1990 by J. G. Ballard. Design and introduction copyright © 1990 by Re/Search Publications. Paperback: ISBN 0-940642-18-2 Limited edition of 300 autographed hardbacks: ISBN 0-940642-19-0 BOOKSTORE DISTRIBUTION: Consortium, 1045 Westgate Drive, Suite 90, Saint Paul, MN 55114-1065. TOLL FREE: 1-800-283-3572. TEL: 612-221-9035. FAX: 612-221-0124 NON-BOOKSTORE DISTRIBUTION: Last Gasp, 777 Florida Street, San Francisco, CA 94110. TEL: 415-824-6636. FAX: 415-824-1836 U.K. DISTRIBUTION: Airlift, 26 Eden Grove, London N7 8EL TEL: 071-607-5792. FAX: 071-607-6714 LETTERS, ORDERS & CATALOG REQUESTS TO: RE/SEARCH PUBLICATIONS SEND SASE 20ROMOLOST#B FOR SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94133 CATALOG PH (415) 362-1465 FAX (415) 362-0742 REQUESTS Printed in Hong Kong by Colorcraft Ltd. 10987654 Front Cover and all illustrations by Phoebe Gloeckner Back Cover and all photographs by Ana Barrado Endpapers: "Mucous and serous acini, sublingual gland" by Phoebe Gloeckner Phoebe Gloeckner (M.A. Biomedical Communication, Univ. Texas) is an award-winning medical illustrator whose work has been published internationally. She has also won awards for her independent films and comic art, and edited the most recent issue of Wimmin's Comix published by Last Gasp. Currently she resides in the San Francisco Bay Area. Ana Barrado is a photographer whose work has been exhibited in Italy, Mexico City, Japan the United States. -

MAKING MEANING of EXTREME FLESH PRACTICES by Alicia D

PULLING TOGETHER: MAKING MEANING OF EXTREME FLESH PRACTICES By Alicia D. Horton A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY IN CONFORMITY WITH THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS QUEEN‟S UNIVERSITY KINGSTON, ONTARIO, CANADA APRIL 2010 Copyright Alicia D. Horton, 2010 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-70025-9 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-70025-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Becoming Heavily Tattooed in the Postmodern West: Sacred Rite

Becoming heavily tattooed in the postmodern West: sacred rite, 'Modern Primitivism', or profane simulation? by Fareed Kaviani Thesis submitted as partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Hons.) Sociology, Anthropology and International Development Department of Social Inquiry La Trobe University October 2017 1 Statement of Authorship This thesis is my own work containing, to the best of my knowledge and belief, no material published or written by another person except as referred to in the text. 18 / 10 / 17 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Sara James, for her generous support, patience, time and knowledge, and Anthony Moran, for his tireless administrative assistance. 2 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 1 .................................................................................................................................. 11 Premodern Tatau and Tattoo: The Makings of the ‘Noble Savage’ ........................................ 11 Premodern Tatau ................................................................................................................. 11 Rite of Passage and Sacredness ........................................................................................... 12 Premodern European