San Francisquito Creek—The Problem of Science in Environmental Disputes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dam Removal Planning in the California Coast Ranges by Clare

The Big Five: Dam Removal Planning in the California Coast Ranges by Clare Kathryn O’Reilly A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Landscape Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor G. Mathias Kondolf, Chair Professor Randolph T. Hester Professor Emeritus Robert Twiss Spring 2010 The thesis of Clare Kathryn O’Reilly, titled The Big Five: Dam Removal Planning in the California Coast Ranges, is approved: Chair Date: Professor G. Mathias Kondolf Date: Professor Randolph T. Hester Date: Professor Emeritus Robert Twiss University of California, Berkeley Spring 2010 The Big Five: Dam Removal Planning in the California Coast Ranges Copyright 2010 by Clare O’Reilly Table of Contents CHAPTER 1: Introduction 1 CHAPTER 2: Methods 18 CHAPTER 3: Conceptual Framework 22 CHAPTER 4: Case Studies 46 Upper York Creek Dam 47 Searsville Dam 58 San Clemente Dam 72 Matilija Dam 84 Rindge Dam 99 CHAPTER 5: Synthesis & Recommendations 108 REFERENCES 124 APPENDICES 136 table OF COnTEnTS i List of Figures CHAPTER 1 Figure 1-1. Sediment deposition from upstream watershed (left) and resulting deposition in reservoir. 2 Figure 1-2. Transport impact of dams. (Wildman, 2006) 3 Figure 1-3. Dams in the US by height. (USACE, 2009) 3 Figure 1-4. Dams in the US by hazard potential. (USACE, 2009) 3 Figure 1-5. Delta deposition in reservoir. (Mahmood, 1987) 5 Figure 1-6. Example of reservoir sediment deposit. 5 Figure 1-7. Infilled reservoir. (Morris & Fan, 1998) 5 Figure 1-8. Bar-lin Dam on the Dahan River in Taiwan, full of sediment in 2006 four years after completion (left), and post-failure in 2007 (right). -

BAYLANDS & CREEKS South San Francisco

Oak_Mus_Baylands_SideA_6_7_05.pdf 6/14/2005 11:52:36 AM M12 M10 M27 M10A 121°00'00" M28 R1 For adjoining area see Creek & Watershed Map of Fremont & Vicinity 37°30' 37°30' 1 1- Dumbarton Pt. M11 - R1 M26 N Fremont e A in rr reek L ( o te C L y alien a o C L g a Agua Fria Creek in u d gu e n e A Green Point M a o N l w - a R2 ry 1 C L r e a M8 e g k u ) M7 n SF2 a R3 e F L Lin in D e M6 e in E L Creek A22 Toroges Slou M1 gh C ine Ravenswood L Slough M5 Open Space e ra Preserve lb A Cooley Landing L i A23 Coyote Creek Lagoon n M3 e M2 C M4 e B Palo Alto Lin d Baylands Nature Mu Preserve S East Palo Alto loug A21 h Calaveras Point A19 e B Station A20 Lin C see For adjoining area oy Island ote Sand Point e A Lucy Evans Lin Baylands Nature Creek Interpretive Center Newby Island A9 San Knapp F Map of Milpitas & North San Jose Creek & Watershed ra Hooks Island n Tract c A i l s Palo Alto v A17 q i ui s to Creek Baylands Nature A6 o A14 A15 Preserve h g G u u a o Milpitas l Long Point d a S A10 A18 l u d p Creek l A3N e e i f Creek & Watershed Map of Palo Alto & Vicinity Creek & Watershed Calera y A16 Berryessa a M M n A1 A13 a i h A11 l San Jose / Santa Clara s g la a u o Don Edwards San Francisco Bay rd Water Pollution Control Plant B l h S g Creek d u National Wildlife Refuge o ew lo lo Vi F S Environmental Education Center . -

Section 8: the Current Permitting Process for Projects Proposed on San Francisquito Creek

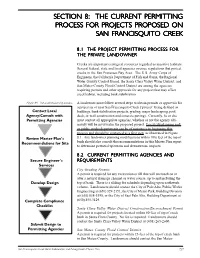

SECTION 8: THE CURRENT PERMITTING PROCESS FOR PROJECTS PROPOSED ON SAN FRANCISQUITO CREEK 8.1 THE PROJECT PERMITTING PROCESS FOR THE PRIVATE LANDOWNER Creeks are important ecological resources regarded as sensitive habitats. Several federal, state and local agencies oversee regulations that protect creeks in the San Francisco Bay Area. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the California Department of Fish and Game, the Regional Water Quality Control Board, the Santa Clara Valley Water District, and San Mateo County Flood Control District are among the agencies requiring permits and other approvals for any project that may affect creek habitat, including bank stabilization. Figure 8A The project planning process A landowner must follow several steps to obtain permits or approvals for a project in or near San Francisquito Creek (‘project’ being defined as Contact Local buildings, bank stabilization projects, grading, major landscaping, pool, Agency/Consult with deck, or wall construction and concrete paving). Currently, he or she Permitting Agencies must contact all appropriate agencies, whether or not the agency ulti- mately will be involved in the proposed project. Local city planning and/ or public works departments can be of assistance in beginning this process and should be contacted as a first step, as illustrated in Figure Review Master Plan’s 8.1. Any landowner planning modifications within fifty feet of the top of Recommendations for Site bank should also consult the recommendations in this Master Plan report to determine potential upstream and downstream impacts. 8.2 CURRENT PERMITTING AGENCIES AND Secure Engineer’s REQUIREMENTS Services City Grading Permits A permit is required for any excavation or fill that will encroach on or alter a natural drainage channel or water course, up to and including the Develop Design top of bank. -

Goga Wrfr.Pdf

The National Park Service Water Resources Division is responsible for providing water resources management policy and guidelines, planning, technical assistance, training, and operational support to units of the National Park System. Program areas include water rights, water resources planning, regulatory guidance and review, hydrology, water quality, watershed management, watershed studies, and aquatic ecology. Technical Reports The National Park Service disseminates the results of biological, physical, and social research through the Natural Resources Technical Report Series. Natural resources inventories and monitoring activities, scientific literature reviews, bibliographies, and proceedings of technical workshops and conferences are also disseminated through this series. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the National Park Service. Copies of this report are available from the following: National Park Service (970) 225-3500 Water Resources Division 1201 Oak Ridge Drive, Suite 250 Fort Collins, CO 80525 National Park Service (303) 969-2130 Technical Information Center Denver Service Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225-0287 Cover photos: Top: Golden Gate Bridge, Don Weeks Middle: Rodeo Lagoon, Joel Wagner Bottom: Crissy Field, Joel Wagner ii CONTENTS Contents, iii List of Figures, iv Executive Summary, 1 Introduction, 7 Water Resources Planning, 9 Location and Demography, 11 Description of Natural Resources, 12 Climate, 12 Physiography, 12 Geology, 13 Soils, 13 -

Climate Change Adaptation in Action

Climate Change Adaptation in Action San Francisquito Creek Joint Powers Authority Factors Future Sea Level Rise Into Coordinated, Watershed-Level Flood Protection Synopsis Many Bay Area communities are facing increased against a 100-year San Franciscquito creek flow flood risk as sea level continues to rise and storm event happening at the same time as a 100-year and flooding events potentially become more high tide event that is marked by a sea level rise of intensei. Communities along the San Francisquito 26 inches. The SFCJPA assumed this design would creek are no exception, and sea level rise stands be resilient for 50 years using Army Corps of Engi- to exacerbate existing flood protection challenges neers standards. For this proposed project, finding that have occurred in the past with heavy storms common ground among all interested parties was causing millions of dollars in damages. The San key to incorporating innovative flood protection Francisquito Creek Joint Powers Authority (SFCJPA), techniques. To address the diverse interests of the covering a 30,000 acre watershed, has sought to SFCJPA partners and project stakeholders, the fun- address these challenges by working to simultane- damental goal is to change this waterway from one ously improve flood protection, recreational op- that divides multiple, neighboring communities portunities and habitat benefits to multiple commu- into one that unites them around a more natural nitiesii . The SFCJPA San Francisco Bay to Highway water runoff system that is less prone to flooding. 101 flood protection project is designed to protect San Francisquito Watershed Boundaries and Land Ownership THE LAY OF THE LAND The San Francisquito creek watershed covers 46 square miles and includes six towns (Menlo Park, East Palo Alto, Palo Alto, Woodside, Portola Valley, Atherton); two county flood control districts; local, state and national park sites; major rail routes and highways; a regional airport; and numerous other critical facilities. -

Historical Status of Coho Salmon in Streams of the Urbanized San Francisco Estuary, California

CALIFORNIA FISH AND GAME California Fish and Game 91(4):219-254 2005 HISTORICAL STATUS OF COHO SALMON IN STREAMS OF THE URBANIZED SAN FRANCISCO ESTUARY, CALIFORNIA ROBERT A. LEIDY1 U. S. Environmental Protection Agency 75 Hawthorne Street San Francisco, CA 94105 [email protected] and GORDON BECKER Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration 4179 Piedmont Avenue, Suite 325 Oakland, CA 94611 [email protected] and BRETT N. HARVEY Graduate Group in Ecology University of California Davis, CA 95616 1Corresponding author ABSTRACT The historical status of coho salmon, Oncorhynchus kisutch, was assessed in 65 watersheds surrounding the San Francisco Estuary, California. We reviewed published literature, unpublished reports, field notes, and specimens housed at museum and university collections and public agency files. In watersheds for which we found historical information for the occurrence of coho salmon, we developed a matrix of five environmental indicators to assess the probability that a stream supported habitat suitable for coho salmon. We found evidence that at least 4 of 65 Estuary watersheds (6%) historically supported coho salmon. A minimum of an additional 11 watersheds (17%) may also have supported coho salmon, but evidence is inconclusive. Coho salmon were last documented from an Estuary stream in the early-to-mid 1980s. Although broadly distributed, the environmental characteristics of streams known historically to contain coho salmon shared several characteristics. In the Estuary, coho salmon typically were members of three-to-six species assemblages of native fishes, including Pacific lamprey, Lampetra tridentata, steelhead, Oncorhynchus mykiss, California roach, Lavinia symmetricus, juvenile Sacramento sucker, Catostomus occidentalis, threespine stickleback, Gasterosteus aculeatus, riffle sculpin, Cottus gulosus, prickly sculpin, Cottus asper, and/or tidewater goby, Eucyclogobius newberryi. -

Historic Element

Town of Portola Valley General Plan Historic Element Last amended April 22, 1998 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 Background of Community ......................................................................................................... 1 Purpose ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Scope ........................................................................................................................................... 2 Definitions ................................................................................................................................... 2 Objectives ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Principles ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Standards ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Historic Resource to be Preserved .............................................................................................. 4 Historic Resource to be Noted with a Plaque ............................................................................. 5 Historic Resource Listed for Further -

Stonybrook Creek Cleanup – Sunday, December 2

Stonybrook Creek Cleanup – Sunday, December 2 The Alameda Creek Alliance will sponsor a trash pickup along Stonybrook Creek on Sunday, December 2, in the late afternoon. Help us get the last of the trash out of this important trout stream before the rains come. Meeting location to be announced. To participate, contact the Alameda Creek Alliance volunteer coordinator, Ralph Boniello, at [email protected] Alameda Creek Watershed Christmas Bird Count – Friday, December 14 The Alameda Creek Alliance and Ohlone Audubon Society are looking for dedicated birders to help with the fourth annual Eastern Alameda County Christmas Bird Count on Friday, December 14. You can also participate by monitoring your backyard bird feeders on that day. The count circle is in the vicinity of the towns of Sunol, Pleasanton and Livermore, and includes five East Bay Regional Parks, significant SFPUC watershed lands, and exciting East Bay birding hotspots such as lower Mines Road, Sunol Wilderness, Calaveras Reservoir, Lawrence Livermore National Lab, and Springtown Preserve. Please contact Rich Cimino ([email protected]) for more information. This year’s count is being conducted in memory of Bob Several, reporter, editorialist and photographer for the Livermore Independent newspaper. Bob was a conservationist and a strong advocate for protection of Sunol Ridge and Pleasanton Ridge, fought for the Pleasanton urban growth boundary, championed the Alameda County urban growth boundary and the Livermore urban growth boundary known as Measure D. Today birders enjoy the open space lands Bob fought to protect in eastern Alameda County, many of which are part of the CBC. Bob passed on September 21, 2012. -

4.8 Hydrology and Water Quality

Redwood City New General Plan 4.8 Hydrology and Water Quality 4.8 HYDROLOGY AND WATER QUALITY This section discusses surface waters, groundwater resources, storm water collection and transmission, and flooding characteristics in the plan area. Key sources of information for this section include the San Francisco Bay Basin Water Quality Control Plan (Basin Plan) prepared by the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board (January 2007), the Urban Water Management Plan (UWMP) for the City of Redwood City (2005), and the Unified Stream Assessment in Seven Watersheds in San Mateo County, California by the San Mateo Countywide Water Pollution Prevention Program (August 2008), Kennedy/Jenks/Chilton Consulting Engineers Water, Sewer Storm Drainage Master Plan dated 1986, and Winzler & Kelly’s Bayfront Canal Improvement Project Design Development Alternative Analysis, dated December 2003. 4.8.1 ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING Hydrologic Conditions The regional climate of the plan area is typical of the San Francisco Bay Area and is characterized by dry, mild summers and moist, cool winters. Average annual precipitation in the plan area is about 20 inches. About 80 percent of local precipitation falls in the months of November through March. Over the last century for which precipitation records are available, annual precipitation has ranged from an historic low of 8.01 inches in 1976 to an historic high of 42.82 inches in 1983.1 Surface Waters Figure 4.4-1 (in Section 4.4, Biological Resources) depicts surface water bodies in the plan area, which include Redwood and Cordilleras Creeks and their tributaries. Also shown are bay channels, including Westpoint Slough, Corkscrew Slough, northerly reaches of Redwood Creek, Smith Slough and Steinberger Slough, the Atherton Channel (Marsh Creek), and the Bay Front Canal. -

Collaborative Research Phase Week 3 Tour | San Mateo County

Collaborative Research Phase Week 3 Tour | San Mateo County Reports from the Field Collaborative Research Phase Week 3// October 16th Locations// South San Francisco, Burlingame, Menlo Park, San Mateo, Cooley Landing. Tour // San Mateo county SAN BRUNO / COLMA CREEK TOUR In the morning we all gathered at Oyster Point, where San Mateo County officials gave us an introduction to the tremendous exposure to vulnerabilities that are present in San Mateo. We visited the South San Francisco Water Quality control plant, and observed the area from a high point directly adjacent to SFO. Standing at the confluence of San Bruno creek and Colma Creek directly adjacent to industry, we learned of opportunities for subsurface detention. A lot of work has been put into hard armoring strategies to protect SFO, because of the risk of placing wetland habitats in close proximity to planes. BAIR ISLAND After lunch, we had short walking tour of Bair Island with Ivette Loredo a wildlife Refuge Specialist, and Ahmad Haya a senior civil engineer with Redwood City. It was great to see an example indicative of what the middle of the San Francisco Bay shoreline once was. This tour revealed that there is restoration potential underway, and the inner Bair island restoration has proven to be successful so far, with a whole new swath of vegetative growth just since 2016. BEDWELL BAYFRONT PARK The former landfill site is a well adored and utilized park for San Mateo County residents. Joined by Kristen Keith the Mayor of Menlo Park, they are working to receive public input surrounding resiliency measures. -

Be Part of the Sollution to Creek Pollution. Visit Or Call (408) 630-2739 PRESENTED BY: Creek Connections Action Group DONORS

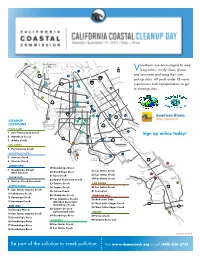

1 San Francisco Bay Alviso Milpitas olunteers are encouraged to wear CREEK ty 2 STEVENS si r CR e iv Palo SAN FRANCISQUITO long pants, sturdy shoes, gloves n E 13 U T N Alto 3 N E V A P l N Mountain View i m A e d a M G R U m E A and sunscreen and bring their own C P 7 D O s o MATADERO CREEK A Y era n L O T av t Car U E al Shoreline i L‘Avenida bb C ean P K E EE R a C d C SA l R S pick-up sticks. All youth under 18 need i E R RY I V BER h t E E r R a E o F 6 K o t M s K o F EE t g CR h i IA i n r C supervision and transportation to get l s N l e 5 t E Ce T R t n 9 S I t tra 10 t N e l E ADOBE CREEK P 22 o Great America Great C M a to cleanup sites. p i to Central l e Exp Ke Mc W e h s c s i r t a n e e e k m r El C w c a o 15 4 o o m w in T R B o a K L n in SI a Santa Clara g um LV S Al ER C Sunnyvale R 12 16 E E K 11 ry Homestead 17 Sto S y T a l H n e i 18 O F K M e Stevens Creek li 19 P p S e O O y yll N N ll I u uT l C U T l i R Q h A t R 23 26 C S o Cupertino 33 20 A S o ga O o M T F t Hamilton A a O a G rba z r Ye B T u 14 S e 8 a n n d n O a R S L a 24 A N i A 32 e S d CLEANUP 34 i D r M S SI e L K e V o n E E R E Campbell C n t M R R 31 e E E C t K e r STEVENS CREEK LOCATIONS r S Campbell e y RESERVOIR A Z W I m San L e D v K A CA A E o S E T r TE R e V C B c ly ENS el A s Jose H PALO ALTO L C A a B C a HELLYER 28 m y 30 xp w 1 San Francisquito Creek d Capitol E PARK o r e t e n Saratoga Saratoga i t Sign up online today! u s e Q h 21 C YO c O T 2 Matadero Creek E n i C W R E ARATOGA CR E S 29 K 3 Adobe Creek VASONA RESERVOIR -

Section 2 Physical/Biological Setting, Including Covered Species

SECTION 2 PHYSICAL/BIOLOGICAL SETTING, INCLUDING COVERED SPECIES 2.0 PHYSICAL / BIOLOGICAL SETTING, INCLUDING COVERED SPECIES 2.1 SIGNIFICANT HYDROLOGIC FEATURES 2.1.1 San Francisquito Creek Watershed The San Francisquito Creek watershed encompasses an area of approximately 45 square miles and is located on the east- ern flank of the Santa Cruz Mountains, at the base of the San Francisco Peninsula (Fig. 2-1). This watershed is located in two counties, San Mateo and Santa Clara, and two of its constituent creeks (Los Trancos and San Francisquito) form part of the boundary between the two counties. The San Francisquito Creek watershed has four major sub-watersheds located at least partially on Stanford lands: Bear Creek (Bear When this HCP was prepared, Stanford had the following Gulch Creek), Los Trancos Creek, San Francisquito Creek, and functioning water diversion facilities in the San Francisquito streams that flow into Searsville Reservoir (including Corte Creek system: Searsville Dam and Reservoir, located down- Madera, Dennis Martin, Sausal, and Alambique creeks). stream from the confluence of Corte Madera Creek and Sausal Creek; Los Trancos diversion on Los Trancos Creek, near A USGS gauging station (11164500) is located on San the intersection of Arastradero and Alpine roads; and an in- Francisquito Creek near the Stanford golf course, approxi- channel pumping station, located in San Francisquito Creek mately 500 meters south (upstream) of the Junipero Serra near the Stanford golf course, south of the Junipero Serra Boulevard/Alpine Road intersection. This station has been in Boulevard/Alpine Road intersection. Another diversion facil- operation since the early 1930s.