Don Edwards SF Bay NWR Final Comprehensive Conservation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Silicon Valley Chapter Military Officers Association of America

Silicon Valley Chapter Military Officers Association of America Volume XII Issue 11The Bulletin Dec 2015 OFFICERS, BOARD, AND CHAIRS PRESIDENT: Lt. Col. Mike Sampognaro USAF merry christmas to all 408-779-7389 1st VP: Lt. Col. Jay Craddock USAF 650-968-0446 2nd VP: CWO5 Robert Landgraf USMC 408-323-8838 Secretary: COL Warren Enos AUS Luncheon Program 408-245-2217 Treasurer: CAPT Lloyd McBeth USN 408-241-3514 17 Dec 2015 Past President: CAPT Paul Barrish USN 408-356-7531 Touring Morocco DIRECTORS & COMMITTEE CHAIRS Auxiliary Liaison vacant Chaplain Chaplain Fred Tittle USMC 609-802-3492 Commissary/Exchange Advisory CDR Ralph Hunt USN 650-967-8467 Friends-in-Need (FIN) Program CDR Al Mouns USN 408-257-5629 Programs Lt. Col. Jesse Craddock USAF 650-968-0446 ROTC CWO4 Patrick Clark USA 831-402-8548 Membership/Recruitment CWO5 Robert Landgraf USMC 408-323-8838 Scholarship CAPT Paul Barrish USN 408-356-7531 Travel (Space-A Advisory) CDR V.A. Eagye USN 408-733-3177 Web Master Lt Col Mike Sampognaro USAF 408-779-7389 Veteran Affairs Col Keith Giles,USAF(ret) Lt Col Neil Miles USAF 408-929-1142 Development Officer CAPT Gil Borgardt USN 650-342-1270 Sargeant-at-Arms Social Hour: 11:00 AM CDR Ralph Hunt USN 650-967-8467 Chapter Outreach CWO5 Robert Landgraf USMC 408-323-8838 Luncheon: 11:45 AM CALMOAA, Legislation & Navy League Liaison LCDR Tom Winant USN 650-678-7120 Luncheon is $26.00 Personal Affairs CAPT Robert French USN 650-363-1188 See Back Page for Reservations Form and Directions The Chapter Board meets at the Moffett Air Traffic Control Tower, Moffett Federal Airfield Bulletin Editor It is time to renew your Lt. -

NSIAD-95-133 Military Bases: Analysis of DOD's 1995 Process

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Congress and the GAO Chairman, Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission April 1995 MILITARY BASES Analysis of DOD’s 1995 Process and Recommendations for Closure md Realignment GAO/NSIAD-95-133 National Security and International Affairs Division B-26 1024 April 14,1995 To the President of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives The Honorable Alan J. Dixon Chairman, Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission The Secretary of Defense announced his 1995 recommendations for base closures and realignments to the Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission on February 28,1995. This report responds to the Defense Base Closure and Realignment Act of 1990 (P.L. 101~510), as amended, which requires that we provide the Congress and the Commission, by no later than April 15,1995, a report on the recommendations and selection process. We have identified issues for consideration by the Commission as it completes its review of the Secretary of Defense’s recommendations. Given that this is the last of three biennial reviews authorized under the 1990 act, we are also including matters for consideration by the Congress regarding the potential need for continuing Iegislation to authorize further commission reviews and authorize changes, as needed, to prior decisions We are sending copies of this report to the Chairmen, Senate Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on Defense; Senate Committee on Armed Services; House Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on National Security; House Committee on National Security; the Secretaries of Defense, the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force; and the Directors of the Defense Logistics Agency and the Defense Investigative Service. -

Regional Economic Impacts of Current and Proposed Management Alternatives for Don Edwards National Wildlife Refuge

Regional Economic Impacts of Current and Proposed Management Alternatives for Don Edwards National Wildlife Refuge By Leslie Richardson, Chris Huber, and Lynne Koontz Open-File Report 2012–1094 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey i U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia 2012 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Suggested citation: Richardson, Leslie, Huber, Chris, and Koontz, Lynne, 2012, Regional economic impacts of current and proposed management alternatives for Don Edwards National Wildlife Refuge: U.S. Geological Survey, Open-File Report 2012–1094, 19 p. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Regional Economic Setting -

Ocean Shore Management Plan

Ocean Shore Management Plan Oregon Parks and Recreation Department January 2005 Ocean Shore Management Plan Oregon Parks and Recreation Department January 2005 Oregon Parks and Recreation Department Planning Section 725 Summer Street NE Suite C Salem Oregon 97301 Kathy Schutt: Project Manager Contributions by OPRD staff: Michelle Michaud Terry Bergerson Nancy Niedernhofer Jean Thompson Robert Smith Steve Williams Tammy Baumann Coastal Area and Park Managers Table of Contents Planning for Oregon’s Ocean Shore: Executive Summary .......................................................................... 1 Chapter One Introduction.................................................................................................................. 9 Chapter Two Ocean Shore Management Goals.............................................................................19 Chapter Three Balancing the Demands: Natural Resource Management .......................................23 Chapter Four Balancing the Demands: Cultural/Historic Resource Management .........................29 Chapter Five Balancing the Demands: Scenic Resource Management.........................................33 Chapter Six Balancing the Demands: Recreational Use and Management .................................39 Chapter Seven Beach Access............................................................................................................57 Chapter Eight Beach Safety .............................................................................................................71 -

3. Project Description March 5, 2003 Page 3-1

Marina Shores Village Project Draft EIR City of Redwood City 3. Project Description March 5, 2003 Page 3-1 3. PROJECT DESCRIPTION This chapter describes the proposed action or "project" addressed by this EIR. The description is based on information provided to the City by the project applicant, Glenborough-Pauls LLC. As stipulated by the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) Guidelines, the project description has been detailed to the extent needed for adequate review and evaluation of environmental impacts. In addition to describing key elements of the proposed project, this chapter is supplemented by project description details in individual environmental chapters 4 through 15. The description that follows includes (a) the project setting (location, boundaries, and local setting of the project site); (b) the project background (site history); (c) a statement of the basic project objectives sought by the applicant; (d) the project's physical and operational characteristics (i.e., land use components, densities, building types, architectural design, landscaping/open space, circulation and parking plans, marina and shoreline modifications, infrastructure provisions, project management, and other pertinent features); (e) the anticipated project construction schedule; and (f) the various anticipated permits and jurisdictional approvals required to allow construction of the project. 3.1 PROJECT SETTING 3.1.1 Regional Location As illustrated on Figure 3.1 (Regional Map), the proposed project site is located at the northern edge of the developed portion of Redwood City, on the San Francisco Bay side of U.S. Highway 101 (Bayshore Freeway). U.S. 101 provides regional access to the approximately 46.45-acre project site; East Bayshore Road and Bair Island Road provide local access. -

San Francisco Bay Crossings Study Recommendation Summary

RECOMMENDATION SUMMARY San Fran c isco Bay July 2002 -----=~Jro:;~~~~ ~ ___________________Crossings Study After more than a year of careful study, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) is preparing final recommendations for a strategy to not only ease the congestion plaguing various routes across San Froncisco Bay but to help deal with a projected 40 percent increase in transbay travel by 2025. Responding to a request by U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein that a 1991 study be updated, MTC launched the San Francisco Bay Crossings Study in late 2000 and began analyzing the costs, travel impacts and environmental issues associated with a long list of options for three primary trans bay corridors: San Francisco-Oakland, San Mateo-Hayward and the Dumbarton Bridge corridors. Study Team Tackles Tough Questions The Bay Crossings Study team, which includes staff from MTC While the policy committee's draft recommendations focus on and other agencies, is led by a 13-member policy committee lower-cost improvements that could start going into place with (see box on page 6). The team's mission was to balance limit in months - and could be paid for with existing funds or a pos ed funds with the growing need for congestion relief on the sible $1 increase in tolls on state-owned toll bridges - it also three existing bridges and in BART's transbay tube. This raised recommends further investigation of a new mid-Bay bridge and a series of critical questions: Should we build a new crossing other big-ticket projects that could take many years to complete or try to move more people through existing corridors? Should and for which no funding sources have yet been identified. -

BAYLANDS & CREEKS South San Francisco

Oak_Mus_Baylands_SideA_6_7_05.pdf 6/14/2005 11:52:36 AM M12 M10 M27 M10A 121°00'00" M28 R1 For adjoining area see Creek & Watershed Map of Fremont & Vicinity 37°30' 37°30' 1 1- Dumbarton Pt. M11 - R1 M26 N Fremont e A in rr reek L ( o te C L y alien a o C L g a Agua Fria Creek in u d gu e n e A Green Point M a o N l w - a R2 ry 1 C L r e a M8 e g k u ) M7 n SF2 a R3 e F L Lin in D e M6 e in E L Creek A22 Toroges Slou M1 gh C ine Ravenswood L Slough M5 Open Space e ra Preserve lb A Cooley Landing L i A23 Coyote Creek Lagoon n M3 e M2 C M4 e B Palo Alto Lin d Baylands Nature Mu Preserve S East Palo Alto loug A21 h Calaveras Point A19 e B Station A20 Lin C see For adjoining area oy Island ote Sand Point e A Lucy Evans Lin Baylands Nature Creek Interpretive Center Newby Island A9 San Knapp F Map of Milpitas & North San Jose Creek & Watershed ra Hooks Island n Tract c A i l s Palo Alto v A17 q i ui s to Creek Baylands Nature A6 o A14 A15 Preserve h g G u u a o Milpitas l Long Point d a S A10 A18 l u d p Creek l A3N e e i f Creek & Watershed Map of Palo Alto & Vicinity Creek & Watershed Calera y A16 Berryessa a M M n A1 A13 a i h A11 l San Jose / Santa Clara s g la a u o Don Edwards San Francisco Bay rd Water Pollution Control Plant B l h S g Creek d u National Wildlife Refuge o ew lo lo Vi F S Environmental Education Center . -

Section 3.4 Biological Resources 3.4- Biological Resources

SECTION 3.4 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES 3.4- BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES 3.4 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES This section discusses the existing sensitive biological resources of the San Francisco Bay Estuary (the Estuary) that could be affected by project-related construction and locally increased levels of boating use, identifies potential impacts to those resources, and recommends mitigation strategies to reduce or eliminate those impacts. The Initial Study for this project identified potentially significant impacts on shorebirds and rafting waterbirds, marine mammals (harbor seals), and wetlands habitats and species. The potential for spread of invasive species also was identified as a possible impact. 3.4.1 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES SETTING HABITATS WITHIN AND AROUND SAN FRANCISCO ESTUARY The vegetation and wildlife of bayland environments varies among geographic subregions in the bay (Figure 3.4-1), and also with the predominant land uses: urban (commercial, residential, industrial/port), urban/wildland interface, rural, and agricultural. For the purposes of discussion of biological resources, the Estuary is divided into Suisun Bay, San Pablo Bay, Central San Francisco Bay, and South San Francisco Bay (See Figure 3.4-2). The general landscape structure of the Estuary’s vegetation and habitats within the geographic scope of the WT is described below. URBAN SHORELINES Urban shorelines in the San Francisco Estuary are generally formed by artificial fill and structures armored with revetments, seawalls, rip-rap, pilings, and other structures. Waterways and embayments adjacent to urban shores are often dredged. With some important exceptions, tidal wetland vegetation and habitats adjacent to urban shores are often formed on steep slopes, and are relatively recently formed (historic infilled sediment) in narrow strips. -

Section 8: the Current Permitting Process for Projects Proposed on San Francisquito Creek

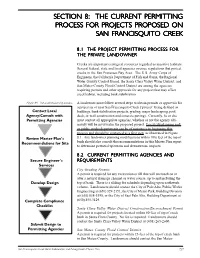

SECTION 8: THE CURRENT PERMITTING PROCESS FOR PROJECTS PROPOSED ON SAN FRANCISQUITO CREEK 8.1 THE PROJECT PERMITTING PROCESS FOR THE PRIVATE LANDOWNER Creeks are important ecological resources regarded as sensitive habitats. Several federal, state and local agencies oversee regulations that protect creeks in the San Francisco Bay Area. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the California Department of Fish and Game, the Regional Water Quality Control Board, the Santa Clara Valley Water District, and San Mateo County Flood Control District are among the agencies requiring permits and other approvals for any project that may affect creek habitat, including bank stabilization. Figure 8A The project planning process A landowner must follow several steps to obtain permits or approvals for a project in or near San Francisquito Creek (‘project’ being defined as Contact Local buildings, bank stabilization projects, grading, major landscaping, pool, Agency/Consult with deck, or wall construction and concrete paving). Currently, he or she Permitting Agencies must contact all appropriate agencies, whether or not the agency ulti- mately will be involved in the proposed project. Local city planning and/ or public works departments can be of assistance in beginning this process and should be contacted as a first step, as illustrated in Figure Review Master Plan’s 8.1. Any landowner planning modifications within fifty feet of the top of Recommendations for Site bank should also consult the recommendations in this Master Plan report to determine potential upstream and downstream impacts. 8.2 CURRENT PERMITTING AGENCIES AND Secure Engineer’s REQUIREMENTS Services City Grading Permits A permit is required for any excavation or fill that will encroach on or alter a natural drainage channel or water course, up to and including the Develop Design top of bank. -

Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge 2020

Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2020 -2021 Waterfowl Hunting Regulations These Regulations along with maps and directions are available at: http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Don_Edwards_San_Francisco_Bay/hunting.html General Information The Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge (refuge) contains approximately 10,580 acres of tidal areas and salt ponds that are open to waterfowl hunting (Map 1). Season opening and closing dates are determined by the State of California. Check the California Waterfowl Regulations (https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Hunting) each season for these dates. Hunters must comply with all State and Federal regulations including regulations listed under 50 CFR 32.24, and the refuge-specific regulations described below. Permit Requirements Hunters 18 years of age or older will need to have: 1) a valid California hunting license; 2) a valid, signed Federal Duck Stamp; 3) a California Duck Validation; 4) a Harvest Information Program (HIP) Validation; and 5) identification that includes a photograph (e.g., driver’s license). Junior and Youth hunters need the following: Junior/Youth Hunter Summary 15 yrs old or 16-17 yrs old w/ Jr 18 yrs old w/ Jr under (Youth) license (Junior) license (Junior) Participate in post-season youth hunt? Yes Yes No Needs a California hunting license? Yes Yes Yes Needs a HIP Validation? Yes Yes Yes Needs a Federal Duck Stamp? No Yes Yes Needs a State Duck Stamp (validation)? No No No Needs an adult accompanying them on regular hunt days? Yes No No Needs an adult accompanying them for youth hunt days? Yes Yes Yes It is required that all hunters possess a Refuge Waterfowl Hunting Permit when hunting in the Alviso Ponds. -

Goga Wrfr.Pdf

The National Park Service Water Resources Division is responsible for providing water resources management policy and guidelines, planning, technical assistance, training, and operational support to units of the National Park System. Program areas include water rights, water resources planning, regulatory guidance and review, hydrology, water quality, watershed management, watershed studies, and aquatic ecology. Technical Reports The National Park Service disseminates the results of biological, physical, and social research through the Natural Resources Technical Report Series. Natural resources inventories and monitoring activities, scientific literature reviews, bibliographies, and proceedings of technical workshops and conferences are also disseminated through this series. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the National Park Service. Copies of this report are available from the following: National Park Service (970) 225-3500 Water Resources Division 1201 Oak Ridge Drive, Suite 250 Fort Collins, CO 80525 National Park Service (303) 969-2130 Technical Information Center Denver Service Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225-0287 Cover photos: Top: Golden Gate Bridge, Don Weeks Middle: Rodeo Lagoon, Joel Wagner Bottom: Crissy Field, Joel Wagner ii CONTENTS Contents, iii List of Figures, iv Executive Summary, 1 Introduction, 7 Water Resources Planning, 9 Location and Demography, 11 Description of Natural Resources, 12 Climate, 12 Physiography, 12 Geology, 13 Soils, 13 -

Birding Northern California by Jean Richmond

BIRDING NORTHERN CALIFORNIA Site Guides to 72 of the Best Birding Spots by Jean Richmond Written for Mt. Diablo Audubon Society 1985 Dedicated to my husband, Rich Cover drawing by Harry Adamson Sketches by Marv Reif Graphics by dk graphics © 1985, 2008 Mt. Diablo Audubon Society All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part by any means without prior permission of MDAS. P.O. Box 53 Walnut Creek, California 94596 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . How To Use This Guide .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Birding Etiquette .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Terminology. Park Information .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 One Last Word. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 Map Symbols Used. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 Acknowledgements .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 Map With Numerical Index To Guides .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 The Guides. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 10 Where The Birds Are. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 158 Recommended References .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 165 Index Of Birding Locations. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 166 5 6 Birding Northern California This book is a guide to many birding areas in northern California, primarily within 100 miles of the San Francisco Bay Area and easily birded on a one-day outing. Also included are several favorite spots which local birders