An Interview with John Holden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Next Schools - 2006-2020

THE LEARNING PROJECT - NEXT SCHOOLS - 2006-2020 2020 2019 2018 Boston College High School (2) Boston College High School Boston Latin Academy Boston Latin School (7) Beaver Country Day School (2) Boston Latin School (5) Brimmer and May Cathedral High School (2) Boston Latin Academy Boston Latin School (5) Fessenden School Dana Hall School (2) Brimmer and May Georgetown Day (Washington, D.C.) The Newman School Linden STEAM Academy Milton Academy The Pierce School Newton Country Day School (2) Thew Newman School The Newman School Newton Country Day School The Rivers School Roxbury Latin School (2) Roxbury Latin School 2017 2016 2015 BC High (2) BC High Boston Latin School (6) Boston Latin Academy Beaver Country Day (2) BC High Boston Latin School (8) Boston Latin School (4) Belmont Hill Brimmer and May Buckingham, Brown, & Nichols Buckingham, Browne & Nichols Milton Academy Fessenden Cathedral High Thayer Academy John D. O’Bryant High School Park School Ursuline Milton Academy (2) Rivers Newton Country Day Winsor (3) Winsor Other Public (2) 2014 2013 2012 Boston Latin School (9) Boston Latin Academy Boston Latin Academy Buckingham, Browne & Nichols (3) Boston Latin School (5) Boston Latin School (9) Catholic Memorial Beaver Country Day BC High Roxbury Latin School (2) BC High Brimmer & May Brimmer & May (2) Cambridge Friends Milton Academy Milton Academy Newton Country Day Shady Hill Roxbury Latin School Ursuline Academy Winsor Concord Public Brookline Public (2) 2011 2010 2009 Boston Latin Academy Boston Latin Academy Boston Latin Academy -

The Boast • December 2018 the Boast • December 2018

A PUBLICATION THE OF CITYSQUASH An Urban Youth Enrichment Program DECEMBER 2018 ROAD SCHOLARS GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK Expanding horizons and making memories through travel. Gatlinburg, TN Middle school students stop to camp in the Appalachian Mountains on their There is something unique about a road trip, where often the journey is as memorable as way to St. Louis. With the growing the destination. It is no surprise that team member feedback consistently rates travel—and the popularity of CitySquash’s Wilderness camaraderie it provides—as the most impactful part of the CitySquash experience. Club, more and more team members are enjoying the outdoors. Travel is introduced as a core part of the CitySquash experience as early as the elementary school level. For many, trips with CitySquash are the first time spent away from home. Our annual team wilderness retreat brings our entire team to Lake Placid, NY for a week of hiking, team- building, and leadership development. During spring break, our staff plans and leads multi-day Spring Enrichment Tours for groups of students. This past year, our six spring tours hit 14 cities WASHINGTON MONUMENT and covered over 7,000 miles. And though sites like the National Aquarium or the Gateway Arch Washington, DC are highlights, it is often the little things that leave the most cherished memories. “I have connected Amaya Diggs gets the perfect shot more with my teammates,” said junior Seth Canales, reminiscing about the high school tour. as part of our Brooklyn team’s trip “My favorite part was when we prepared a meal together. -

Searches Completed 2015 – 2021 Page 1

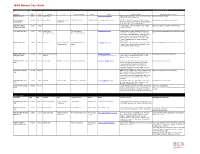

Searches Completed 2015 – 2021 Page 1 Position College/University Person Hired Senior Associate Director Development Babson College Greg Pollard Leadership Giving Officer Bates College Ben Hamilton Leadership Giving Officer Bates College William Bridgeo Director of Corporate Affairs Bentley University Anna Biller Director of Leadership Gifts Bentley University Betsy Whipple Associate Vice President for Development Bowdoin College Mike Archibald Director of Corporate & Foundation Bowdoin College Allison Crosscup Director of the Annual Fund Bowdoin College Christi Razzi Lumiere Leadership Gifts Officer Bowdoin College Kimberly Kubik Associate Director Leadership Giving Dartmouth College Jonathan Cormier Associate Director, Leadership Giving Dartmouth College Betsy Howard Director of Leadership Gifts Dartmouth College Linnell Bickford Vice President for University Advancement Fairfield University Wally Halas VP Strategic Enrollment Management Fairfield University Corry Unis Director of Annual Giving Fairfield University Megan Rajski Associate Vice President, Development Hamilton College Joe Medina Director of Corporate & Foundations Hamilton College Krista Campbell Director of Major Gifts The Jackson Laboratory Nancy Fox Leadership Gift Officer The Jackson Laboratory Mechelle Olortegui Controller The Jackson Laboratory Jason Irwin Manager, Budgets and Planning The Jackson Laboratory Traya Huff Vice President for Finance & Administration Lebanon Valley College Shawn Curtin Director of Budget & Financial Planning Middlebury College Elissa -

Spring 2012 News 4 Getting Inandstaying In

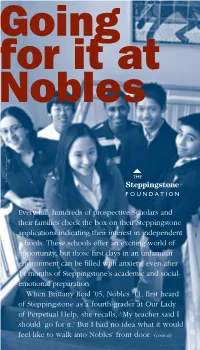

Going for it at Nobles Photo credit: Karen Snyder ® Every fall, hundreds of prospective Scholars and their families check the box on their Steppingstone applications indicating their interest in independent schools. These schools offer an exciting world of opportunity, but those first days in an unfamiliar environment can be filled with anxiety, even after 14 months of Steppingstone’s academic and social- emotional preparation. When Brittany Reid ’05, Nobles ’11, first heard of Steppingstone as a fourth-grader at Our Lady of Perpetual Help, she recalls, “My teacher said I should ‘go for it.’ But I had no idea what it would feel like to walk into Nobles’ front door. (cont’d) Partner School Profile: Noble and Greenough All I knew at the time was that Steppingstone would help me get into a good college, and that’s all I needed to know to want to become a Steppingstone Scholar.” All went according to plan, as Brittany is currently an environmental studies major with a minor in math at Bates College. She also plays ice hockey and rugby, takes drum lessons, and is planning to spend Brittany Reid ’05. her junior-year spring term studying in Copenhagen. In her “spare time,” she works two jobs at Bates, in the financial aid office and the dining hall. But it wasn’t always such smooth sailing for Brittany who grew up in a neighborhood she describes as “plagued by violence.” “When I first got to Nobles, I had an adjustment period. I had never received less than a B+ and was used to being in class Photo credit: Tiffany Tran with almost all students of color. -

NEPSAC Constitution and By-Laws

NEW ENGLAND PREPARATORY SCHOOL ATHLETIC COUNCIL EXECUTIVE BOARD PRESIDENT MARK CONROY, WILLISTON NORTHAMPTON SCHOOL FIRST VICE-PRESIDENT: DAVID GODIN, SUFFIELD ACADEMY SECRETARY: RICHARD MUTHER, TABOR ACADEMY TREASURER: BRADLEY R. SMITH, BRIDGTON ACADEMY TOURNAMENT ADVISORS: KATHY NOBLE, LAWRENCE ACADEMY JAMES MCNALLY, RIVERS SCHOOL VICE-PRESIDENT IN CHARGE OF PUBLICATION: KATE TURNER, BREWSTER ACADEMY PAST PRESIDENTS RICK DELPRETE, HOTCHKISS SCHOOL NED GALLAGHER, CHOATE ROSEMARY HALL SCHOOL MIDDLE SCHOOL REPRESENTATIVES: MIKE HEALY, RECTORY SCHOOL MARK JACKSON, DEDHAM COUNTRY DAY SCHOOL DISTRICT REPRESENTATIVES DISTRICT I BRADLEY R. SMITH, BRIDGTON ACADEMY DISTRICT II KEN HOLLINGSWORTH, TILTON SCHOOL DISTRICT III JOHN MACKAY, ST. GEORGE'S SCHOOL GEORGE TAHAN, BELMONT HILL SCHOOL DISTRICT IV TIZ MULLIGAN , WESTOVER SCHOOL BRETT TORREY, CHESHIRE ACADEMY 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Souders Award Recipients ................................................................ 3 Distinguished Service Award Winners ............................................... 5 Past Presidents ................................................................................. 6 NEPSAC Constitution and By-Laws .................................................. 7 NEPSAC Code of Ethics and Conduct ..............................................11 NEPSAC Policies ..............................................................................14 Tournament Advisor and Directors ....................................................21 Pegging Dates ...................................................................................22 -

Summer/Fall 2013

The Dubliner The Dublin School P.O. Box 522 18 Lehmann Way Dublin, New Hampshire 03444 www.dublinschool.org Address service requested Dubliner Our Mission At Dublin School, we strive to awaken a curiosity for knowledge and a passion for learning. We instill the values of discipline and meaningful work that are necessary for the good of self and community. We respect the individual learning style and unique potential each student brings to our School. With our guidance, Dublin students become men and women who seek truth and act with courage. The Summer/Fall 2013 DublinerThe Magazine of Dublin School Why Sports Matter A New Way with Wood A Nerd’s Eye View SUMMER / FALL 2 0 1 3 1 Dubliner Dublin School Graduation—The Class of 2013 Front row: Jessica Lynne Scharf, Greenfield, NH (University of New Hampshire), Olivia Beatrice Horton-Gregg, Hancock, NH (University of Vermont), Rachel Meredith Coutant, Berwyn, PA (Wells College), Amanda Julia Bartlett, Jaffrey, NH (Lynchburg College), Saioa Ochoa Mendez, Madrid, Spain (Curry College), Xing Xiong, Shenzhen, China (University of Rhode Island), Maria Dolores Espinosa von Wichmann, Madrid, Spain (Art Institute of Boston), Margaret Elliott, Barrington, RI (University of Rhode Island), Elizabeth Takyi, Newark, NJ (Bowdoin College), Emily Marie Beaupré, Cincinnati, OH (Loyola University, Chicago), Alexis Marie Andrus, Spofford, NH (Mt. Holyoke College), Jillian Godard Steele, Rindge/Hancock, NH (Rhode Island School of Design), Stephanie Eve Janetos, Peterborough, NH (University of California, Los Angeles), -

Membership Listing – Fund Year 2020

MEMBERSHIP LISTING – FUND YEAR 2020 Academy at Charlemont Cambridge College, Inc. Academy Hill School Inc Cambridge-Ellis School Academy of Notre Dame at Tyngsboro, Inc. Cambridge Friends School Inc. Allen-Chase Foundation Cambridge Montessori School American Congregational Association The Cambridge School of Weston Applewild School, Inc. Cape Cod Academy, Inc. The Arthur J. Epstein Hillel School The Carroll Center for the Blind, Inc. Assoc of Independent Schools in New England, Inc. Carroll School Atrium School Chapel Hill - Chauncy Hall School Bancroft School Charles River School Bay Farm Montessori Academy The Chestnut Hill School Beaver Country Day School The Children's Museum of Boston Belmont Day School Clark School for Creative Learning Belmont Hill School, Inc. College of the Holy Cross Bement School Common School Benjamin Franklin Institute of Technology Commonwealth School Berkshire Country Day School COMPASS Berkshire Waldorf School, Inc. Concord Antiquarian Society Boston College High School Covenant Christian Academy, Inc. Boston Lyric Opera Company Creative Education Inc dba Odyssey Day School Boston Symphony Orchestra Curry College Inc Boston Trinity Academy Cushing Academy Boston Youth Symphony Orchestras, Inc. Dana Hall School Bradford Christian Academy Inc Dean College Brimmer & May School Dedham Country Day School Brooks School Delphi Academy of Boston Brookwood School, Inc. Derby Academy Buckingham, Browne & Nichols School Dexter Southfield, Inc. Cambridge Center for Adult Education, Inc. Discovery Museums, Inc Eastern Nazarene College MEMBERSHIP LISTING – FUND YEAR 2020 Epiphany School Inc Kingsley Montessori School Falmouth Academy, Inc. Kovago Developmental Foundation, Inc. Family Cooperative Laboure College, Inc. Fay School Lander-Grinspoon Academy Fayerweather Street School Inc Landmark School, Inc. Fenn School Laurel School, Laurel Education Fessenden School Learning Project, Inc. -

Completed National Head of School Searches

CLIENTS SERVED SINCE 2007 Completed National Head of School Searches The Agnes Irwin School, PA (2009) Eagle Hill School, CT (2009) Allen Academy, TX (2014) Echo Horizon School, CA (2014) The Altamont School, AL (2008) Edmund Burke School, DC (2011) American School of Guatemala (2014) Falmouth Academy, MA (2014) The Ancona School, IL (2015) Far Hills Country Day School, NJ (2014) Andover School of Montessori, MA (2007) The Fay School, MA (2008) The Avery Coonley School, IL (2015) The Fay School, TX (2008) The Barrie School, MD (2010) The Fayetteville Academy, NC (2012) Beacon Day School, CA (2014) Fenwick High School, IN (2010) The Benjamin School, FL (2008) The Fessenden School, MA (2008) Berkwood Hedge School, CA (2012) Foothill Country Day School, CA (2011) Boulder Country Day School, CO (2013) Foxcroft Academy, ME (2010) Boys’ Latin School of Maryland (2008) Friends Academy, MA (2012) Brookstone School, GA (2010) Friends School, CO (2011) Brookwood School, MA (2015) George Stevens Academy, ME (2011) Brownell Talbott School, NE (2012) Glen Urquhart School, MA (2012) The Caedmon School, NY (2012) Glenelg Country School, MD (2007) Camp Belknap, NH (2013) Harbor Country Day School, NY (2011) Camp O-AT-KA, ME (2012) Hargrave Military Academy, VA (2011) Camperdown Academy, SC (2008) Hill Top Preparatory School, PA (2007) Chesterfield Day School, MO (2011) Holland Hall, OK (2011) Chinese American International School, CA (2010) Independent Day School, CT (2013) Cold Spring School, CT (2013) Independent Schools Association of the Central -

Tour Guide for Website 6.26.19

IECA Member Tour Guide COLLEGE/UNIVERSITY TOURS revised February 19, 2020 Tour Name Start End Contact Title Contact's School Phone Email Schools Involved Web Registration and Notes BEANS Tour 2020 4/5/20 4/8/20 Liz Desrosiers [email protected] Brandeis University, College of the Holy Cross, Emerson https://www.wpi.edu/c/beans College, Simmons University, WPI Western New York 4/26/20 4/29/20 Nancy Driscoll Associate Director of Alfred State College 1-800-425-3733 [email protected] Alfred State (SUNY), Buffalo State (SUNY), Canisius, http://www.daemen.edu/admissions/collegetour Counselor Tour Admissions Daemen, D'Youville, SUNY Fredonia, Medaille, Niagara U., St. Bonaventure, U. at Buffalo (SUNY) Mid-Hudson Valley 5/4/20 5/6/20 Culinary Institute of America, Marist College, Vassar https://www.marist.edu/admission/mhvcc/schedule College Consortium College, West Point, 2020 Sweet Tea Tour 6/1/20 6/5/20 Bonnie Toliver The First Academy [email protected] Louisian State University, Louisiana Tech University, http://www.sacac.org/professional-development/sweet-tea- Shannon Barrilleaux Metairie Park County Day Loyola University of New Orleans, Tulane University, tour/ University of Louisiana at Lafayette, University of New Orleans, University of Southern Mississippi, Xavier University of Louisiana, Millsaps College, Mississippi College, Mississippi State University (off-campus programming) ICI Counselor Tour 6/8/20 6/10/20 Jen Zentz Director of Strategic Independent Colleges of [email protected] Anderson University, Butler University, -

Ssatb Member Schools in the United States Arizona

SSATB MEMBER SCHOOLS IN THE UNITED STATES ALABAMA CALIFORNIA Indian Springs School Adda Clevenger Pelham, AL San Francisco, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 4084 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1110 Saint Bernard Preparatory School, Inc. All Saints' Episcopal Day School Cullman, AL Carmel, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 6350 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1209 ARKANSAS Athenian School Danville, CA Subiaco Academy SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1414 Subiaco, AR SSAT Score Recipient Code: 7555 Bay School of San Francisco San Francisco, CA ARIZONA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1500 Fenster School Bentley School Tucson, AZ Lafayette, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 3141 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1585 Orme School Besant Hill School of Happy Valley Mayer, AZ Ojai, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 5578 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 3697 Phoenix Country Day School Brandeis Hillel School Paradise Valley, AZ San Francisco, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 5767 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1789 Rancho Solano Preparatory School Branson School Glendale, AZ Ross, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 5997 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 4288 Verde Valley School Buckley School Sedona, AZ Sherman Oaks, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 7930 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1945 Castilleja School Palo Alto, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 2152 Cate School Dunn School Carpinteria, CA Los Olivos, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 2170 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 2914 Cathedral School for Boys Fairmont Private Schools ‐ Preparatory San Francisco, CA Academy SSAT Score Recipient Code: 2212 Anaheim, CA SSAT Score Recipient -

Hms Medscience Survey Highlights Brochure

HMS MEDSCIENCE SURVEY HIGHLIGHTS BROCHURE JULIE JOYAL, RN, M.ED, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR NANCY ORIOL, MD, PRESIDENT & CO-FOUNDER LIVIA RIZZO, PROGRAM DIRECTOR HMS MEDscience is a high school STEM education initiative inspiring students to think without limits and engaging them in science through hands-on experiences. Our mission is to bridge the inspiration gap in STEM education by providing students with opportunities in science that enhance the necessary 21st century skills for success in academic and career settings. The purpose of the survey is to measure student outcomes. Data was collected from 223 students participating in the HMS MEDscience program Fall Semester 2019. Core findings include: LEARNING ENVIRONMENT • 99% of our student participants agree or strongly agree that the pedagogy of the MEDscience program helped them retain and learn the material better. • 96% agree or strongly agree that the cases with the simulator deepened their understanding of biology concepts. BIOLOGY CONTENT • Before the program, only 38% of our participants understood causes and treatments for heart disease. After, 95% reported that they understand the causes and treatments of heart disease. • Students saw similar growths in regards to the understanding the physiological mechanism of an asthma attack and inhaler treatment, and how insulin works in your body in correspondence to diabetes. SELF-EFFICACY, LEADERSHIP & TEAMWORK • 91% report that after participating in HMS MEDscience, he/she is more confident in sharing their ideas in class, even if they might be wrong • 98% of our student participants agree or strongly agree that after participating in HMS MEDscience he/she is comfortable working in teams in emergency situations. -

II Fuess Corres. Box 5

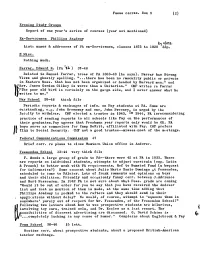

Fuess corres. Box 5 (2) Evening Study Groups Report of one year's series of courses (year not mentioned) Ex-Servicemen Phillips Academy bv fcl<«5. List: names & addresses of PA ex-Servicemen, classes 1875 to 1920 33p. E Misc. Nothing much, Farrar, Edward R. (PA *«?• ) 37-48 Related to Samuel Farrar, treas of PA 1803-40 (he says). Forrar has Strong Views and ghastly spelling, "...there has been no rascality public or private in Eastern Mass. that has not been organized or headed by Harvard men." and Rev. James Gordon Gilkey is worce than a Unitarian." CMF writes re Farrar "The poor old bird is certainly on the ga-ga side, and I never answer what he writes to me." I Fay School 39-48 thick file Periodic reports & exchanges of info, on Fay students at PA. Some are outstanding, e.g. John Greenway and one, John Sweeney, is urged by the faculty to withdraw. CMF elected a trustee in 1943. *n 1944, PA isreconsidering practice of sending reports to all schools like Fay on the performances of their graduates.Fay agrees that Freshman year reports only would be OK. PA boys serve as counselors for Camp DeWitt, affiliated with Fay, CMF prefers TIAA to Social Security. CMF not a good trustee—misses.most of the meetings. II Federal Communications Commission 47 Brief corr. re plans to close Western Union office in Andover. Fessenden School 33-44 very thick file F. Sends a large group of grads to PA—there were 42 at PA in 1933. There are reports on inidvidual students, attempts to adjust curricula (esp.