Staging Intersectionality: Power and Performance in American Cultural Texts, 1855-2019 Alexandra Reznik

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Melissa Jefferson V. Justin Raisen Et

Case 2:19-cv-09107-DMG-MAA Document 79 Filed 04/27/21 Page 1 of 7 Page ID #:489 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA CIVIL MINUTES—GENERAL Case No. CV 19-9107-DMG (MAAx) Date April 27, 2021 Title Melissa Jefferson v. Justin Raisen, et al. Page 1 of 7 Present: The Honorable DOLLY M. GEE, UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE KANE TIEN NOT REPORTED Deputy Clerk Court Reporter Attorneys Present for Plaintiff(s) Attorneys Present for Defendant(s) None Present None Present Proceedings: IN CHAMBERS—ORDER RE PLAINTIFF/COUNTER-DEFENDANT’S MOTION TO DISMISS DEFENDANTS/COUNTERCLAIMANTS’ FIRST AMENDED COUNTERCLAIM [60] On August 14, 2020, the Court granted Plaintiff Melissa Jefferson’s (known professionally as Lizzo) motion to dismiss Defendants Justin Raisen, Jeremiah Raisen, Yves Rothman, and Heavy Duty Music Publishing’s Counterclaims for failure to state a claim, with leave to amend. [Doc. # 57 (“first MTD Order” or “MTD1 Order”).] On September 3, 2020, Counterclaimants filed their First Amended Answer (“FAA”), which contains counterclaims for: (1) a judicial declaration that they are joint authors and co-owners of Truth Hurts; (2) an accounting of revenues from the use of Healthy in Truth Hurts; (3) “further relief” under 28 U.S.C. § 2202; (4) an accounting of revenues from Truth Hurts enjoyed by all Counter-defendants, or by Lizzo and Jesse St. John Geller (“St. John”); and (5) a constructive trust. [Doc. # 58.] On September 24, 2020, Lizzo filed a second motion to dismiss (“MTD”) the first, third, fourth, and fifth amended counterclaims. [Doc. # 60.] The motion has since been fully briefed. -

Pérez Art Museum Miami Announces Exclusive Screening of Solange Knowles’S New Film, When I Get Home

Pérez Art Museum Miami Announces Exclusive Screening of Solange Knowles’s New Film, When I Get Home Screening Concludes PAMM’s Community Night Program, “Art as Film” Thursday, August 1, 6-10PM Film still from Solange’s new film, When I Get Home (2019). WHO/WHAT: Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) is pleased to announce an exclusive screening of the interdisciplinary performance art film When I Get Home (2019) by visual artist and singer/songwriter, Solange Knowles for the museum’s free Community Night on Thursday, August 1. PAMM’s Community Night program, “Art as Film,” features a stellar line-up of selections from Miami’s film producing community through a series of shorts that highlight the best of Miami’s film scene. The program will include presentations from AD Hoc Cinema, Black Lounge Film Series, Coral Gables Cinema, Cosford Cinema, FilmGate, Flaming Classics, Miami Film Festival, Media + Archival Studies, Oolite, and Third Horizon Film Festival. The evening will conclude with an extended director's cut of Solange’s new film, When I Get Home (2019). The film will premiere across renowned museums and contemporary arts institutions across the USA and Europe from July 17, 2019 before closing as part of Chinati Weekend on October 13, 2019 The film was directed and edited by Solange Knowles with contributing directors Alan Ferguson, Terence Nance, Jacolby Satterwhite, and Ray Tintori, with artist contributions that include Houston-based Autumn Knight and Robert Pruitt and sculptural work by the artist, "Boundless Body" an 8 by 100 ft. rodeo arena displayed in the desert of Marfa. -

“A Greater Compass of Voice”: Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield and Mary Ann Shadd Cary Navigate Black Performance Kristin Moriah

Document generated on 10/01/2021 9:01 a.m. Theatre Research in Canada Recherches théâtrales au Canada “A Greater Compass of Voice”: Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield and Mary Ann Shadd Cary Navigate Black Performance Kristin Moriah Volume 41, Number 1, 2020 Article abstract The work of Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield and Mary Ann Shadd Cary URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1071754ar demonstrate how racial solidarity between Black Canadians and African DOI: https://doi.org/10.3138/tric.41.1.20 Americans was created through performance and surpassed national boundaries during the nineteenth century. Taylor Greenfield’s connection to See table of contents Mary Ann Shadd Cary, the prominent feminist abolitionist, and the first Black woman to publish a newspaper in North America, reveals the centrality of peripatetic Black performance, and Black feminism, to the formation of Black Publisher(s) Canada’s burgeoning community. Her reception in the Black press and her performance work shows how Taylor Greenfield’s performances knit together Graduate Centre for the Study of Drama, University of Toronto various ideas about race, gender, and nationhood of mid-nineteenth century Black North Americans. Although Taylor Greenfield has rarely been recognized ISSN for her role in discourses around race and citizenship in Canada during the mid-nineteenth century, she was an immensely influential figure for both 1196-1198 (print) abolitionists in the United States and Blacks in Canada. Taylor Greenfield’s 1913-9101 (digital) performance at an event for Mary Ann Shadd Cary’s benefit testifies to the longstanding porosity of the Canadian/ US border for nineteenth century Black Explore this journal North Americans and their politicized use of Black women’s voices. -

Emerging Artist Recital: Chautauqua Opera Young Artist Program

OPERA AMERICA emerging artist recitals CHAUTAUQUA OPERA YOUNG ARTIST PROGRAM MARCH 14, 2019 | 7:00 P.M. UNCOMMON WOMEN Kayla White, soprano Quinn Middleman, mezzo-soprano Sarah Saturnino, mezzo-soprano Miriam Charney and Jeremy Gill, pianists PROGRAM A Rocking Hymn (2006) Gilda Lyons (b. 1975) Poem by George Wither, adapted by Gilda Lyons Quinn Middleman | Miriam Charney 4. Canción de cuna para dormir a un negrito Poem by Ildefonso Pereda Valdés 5. Canto negro Poem by Nicolás Guillén From Cinco Canciones Negras (1945) Xavier Montsalvatge (1912–2002) Sarah Saturnino | Miriam Charney Lucea, Jamaica (2017) Gity Razaz (b. 1986) Poem by Shara McCallum Kayla White | Jeremy Gill Die drei Schwestern From Sechs Gesänge, Op. 13 (1910–1913) Alexander von Zemlinsky (1871–1942) Poem by Maurice Maeterlinck Die stille Stadt From Fünf Lieder (1911) Alma Mahler (1879–1964) Poem by Richard Dehmel Quinn Middleman | Jeremy Gill [Headshot, credit: Rebecca Allan] Rose (2016) Jeremy Gill (b. 1975) Text by Ann Patchett, adapted by Jeremy Gill La rosa y el sauce (1942) Carlos Guastavino (1912–2000) Poem by Francisco Silva Sarah Saturnino | Jeremy Gill Sissieretta Jones, Carnegie Hall, 1902: O Patria Mia (2018) George Lam (b. 1981) Poem by Tyehimba Jess Kayla White | Jeremy Gill The Gossips From Camille Claudel: Into the Fire (2012) Jake Heggie (b. 1961) Text by Gene Scheer Sarah Saturnino | Jeremy Gill Reflets (1911) Lili Boulanger (1893–1918) Poem by Maurice Maeterlinck Au pied de mon lit From Clairières dans le ciel (1913–1914) Lili Boulanger (1893–1918) Poem by Francis Jammes Quinn Middleman | Miriam Charney Minstrel Man From Three Dream Portraits (1959) Margaret Bonds (1913–1972) Poem by Langston Hughes He had a dream From Free at Last — A Portrait of Martin Luther King, Jr. -

Wesley Historical Society Editor: E

Proceedings OFTHE Wesley Historical Society Editor: E. ALAN ROSE, B.A. Volume 49 October 1993 CHOSEN BY GOD: THE FEMALE TRAVELLING PREACHERS OF EARLY PRIMITIVE METHODISM The Wesley Historical Society Lecture 1993 t is just over a hundred years since the last Primitive Methodist female travelling preacher died. Elizabeth Bultitude (1809-1890) I had become a travelling preacher in 1832 and she superannuated after 30 years in 1862, dying in 1890. Of all the female itinerants the first, Sarah Kirkland (1794-1880), and the last, Elizabeth Bultitude, are the best known, but this is just the tip of the iceberg. Forty years ago Wesley Swift, wrote in the Proceedings about the female preach ers of Primitive Methodism: We have been able to identify more than forty women itinerants, but the full total must be considerably more.\ This was the starting point of my inquiry. First it is necessary to take a brief look at the whole question of women preaching. The Society of Friends, because they maintained both sexes equally received Inner Light, insisted that anyone who felt so called should be allowed to preach. So it was that many women within the Quaker movement were able to exercise their gifts of preaching without restriction. Many women undertook preaching tours both in this country and abroad, finding release from male-dominated society and religion and equal status with I Proceedings, xxix, p 79. 78 PROCEEDINGS OF THE WFSLEY HISTORICAL SocIETY men in preaching the word of God. For many years female preach ing was, on the whole, limited to the Quakers while the other denominations ignored it as being against Scripture, especially the Pauline injunction about women keeping silence in the church. -

Sissieretta Jones Opera

Media Release For Immediate Release Lecture and Recital Celebrate America’s First Black Superstar: Sissieretta Jones Opera Providence presents a lecture and a talk-back about the great Black Diva, Sissieretta Jones of Providence, Rhode Island. Maureen Lee, the foremost scholar on Jones, will discuss how Jones built her international career and navigated the pitfalls of racists and opportunists in 19 th -century America. Lee, author of Sissieretta Jones: “The Greatest Singer of Her Race,” 1868-1933 , will excavate Jones’ world in Black Vaudeville, classical music, her remarkable ability at self-promotion, and her international acclaim singing for presidents and kings. The talk will take place Friday, April 26, 2013, 5:30pm at The Old Brick School House, 24 Meeting Street in Providence, RI. An exhibit of artifacts related to Jones’ singing career will be on display. On Saturday, April 27 at 2 p.m., vocalist Cheryl Albright will sample songs from Jones’ vast and varied repertoire in a recital at the historic Congdon Street Baptist Church, 17 Congdon Street, Providence, RI, where Jones worshipped and sang. Ms. Albright will be accompanied by pianist Rod Luther. The lecture and recital are made possible through a generous grant from the Rhode Island Council for the Humanities. Both events are free and open to the public. Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones of Providence, whose stage name, “Black Patti,” likened her to the renowned Spanish-born opera diva Adelina Patti, was a celebrated African American soprano during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Serving as a role model for other African American stage artists who followed her, Jones became a successful performer despite the obstacles she faced from Jim Crow segregation. -

2020 C'nergy Band Song List

Song List Song Title Artist 1999 Prince 6:A.M. J Balvin 24k Magic Bruno Mars 70's Medley/ I Will Survive Gloria 70's Medley/Bad Girls Donna Summers 70's Medley/Celebration Kool And The Gang 70's Medley/Give It To Me Baby Rick James A A Song For You Michael Bublé A Thousands Years Christina Perri Ft Steve Kazee Adventures Of Lifetime Coldplay Ain't It Fun Paramore Ain't No Mountain High Enough Michael McDonald (Version) Ain't Nobody Chaka Khan Ain't Too Proud To Beg The Temptations All About That Bass Meghan Trainor All Night Long Lionel Richie All Of Me John Legend American Boy Estelle and Kanye Applause Lady Gaga Ascension Maxwell At Last Ella Fitzgerald Attention Charlie Puth B Banana Pancakes Jack Johnson Best Part Daniel Caesar (Feat. H.E.R) Bettet Together Jack Johnson Beyond Leon Bridges Black Or White Michael Jackson Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Boogie Oogie Oogie Taste Of Honey Break Free Ariana Grande Brick House The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl Van Morisson Butterfly Kisses Bob Carisle C Cake By The Ocean DNCE California Gurl Katie Perry Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jespen Can't Feel My Face The Weekend Can't Help Falling In Love Haley Reinhart Version Can't Hold Us (ft. Ray Dalton) Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Can't Get Enough of You Love Babe Barry White Coming Home Leon Bridges Con Calma Daddy Yankee Closer (feat. Halsey) The Chainsmokers Chicken Fried Zac Brown Band Cool Kids Echosmith Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Counting Stars One Republic Country Girl Shake It For Me Girl Luke Bryan Crazy in Love Beyoncé Crazy Love Van Morisson D Daddy's Angel T Carter Music Dancing In The Street Martha Reeves And The Vandellas Dancing Queen ABBA Danza Kuduro Don Omar Dark Horse Katy Perry Despasito Luis Fonsi Feat. -

Get Me Bodied Mp3

Get me bodied mp3 Get Me Bodied. Artist: Beyonce. MB · Get Me Bodied. Artist: Beyonce. MB · Get Me Bodied. Artist: Beyonce. Beyoncé's official video for 'Get Me Bodied' ft. Kelly Rowland, Michelle Williams and Solange Knowles. Buy Get Me Bodied (Extended Mix): Read 28 Digital Music Reviews - Nine, four, eight, one. B-Day Verse 1 mission one. Imma put this on. When he see me in the dress I'ma get me some (hey) mission two. Gotta make that call. Watch the video, get the download or listen to Beyoncé – Get Me Bodied for free. Get Me Bodied appears on the album B'Day. Discover more music, gig and. Watch the video, get the download or listen to Beyoncé – Get Me Bodied (Extended Mix) for free. Get Me Bodied (Extended Mix) appears on the album B'Day. Fabolous & NMC Feat. Beyonce Get Me Bodied free mp3 download and stream. Watch Get Me Bodied (Timbaland Remix) by Beyoncé online at Discover the latest music videos by. Beyonce – Get Me Bodied (Acapella). Artist: Beyonce, Song: Get Me Bodied (Acapella), Duration: , Size: MB, Bitrate: kbit/sec, Type: mp3. Beyoncé's official video for 'Get Me Bodied' ft. Kelly Rowland, Michelle Williams and Solange Knowles (Timbaland Remix). Click to listen to Beyoncé on Spotify. Lyrics to song "Get Me 3" by Beyonce: Get Me Bodied by Beyonce 9 - 4- B-Day Verse 1 Mission One I'ma put this on When he see me in this dress. Beyonce – Get Me Bodied (Extended Mix) – 98 BPM. Categories: s, BPM, Pop. Audio Player. /audio/3. -

Bad Habit Song List

BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song 4 Non Blondes Whats Up Alanis Morissette You Oughta Know Alanis Morissette Crazy Alanis Morissette You Learn Alanis Morissette Uninvited Alanis Morissette Thank You Alanis Morissette Ironic Alanis Morissette Hand In My Pocket Alice Merton No Roots Billie Eilish Bad Guy Bobby Brown My Prerogative Britney Spears Baby One More Time Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Bruno Mars 24K Magic Bruno Mars Treasure Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey Christina Aguilera Fighter Corey Hart Sunglasses at Night Cyndi Lauper Time After Time David Guetta Titanium Deee-Lite Groove Is In The Heart Dishwalla Counting Blue Cars DNCE Cake By the Ocean Dua Lipa One Kiss Dua Lipa New Rules Dua Lipa Break My Heart Ed Sheeran Blow BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song Elle King Ex’s & Oh’s En Vogue Free Your Mind Eurythmics Sweet Dreams Fall Out Boy Beat It George Michael Faith Guns N’ Roses Sweet Child O’ Mine Hailee Steinfeld Starving Halsey Graveyard Imagine Dragons Whatever It Takes Janet Jackson Rhythm Nation Jessie J Price Tag Jet Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jewel Who Will Save Your Soul Jo Dee Messina Heads Carolina, Tails California Jonas Brothers Sucker Journey Separate Ways Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Say Something Katy Perry Teenage Dream Katy Perry Dark Horse Katy Perry I Kissed a Girl Kings Of Leon Sex On Fire Lady Gaga Born This Way Lady Gaga Bad Romance Lady Gaga Just Dance Lady Gaga Poker Face Lady Gaga Yoü and I Lady Gaga Telephone BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song Lady Gaga Shallow Letters to Cleo Here and Now Lizzo Truth Hurts Lorde Royals Madonna Vogue Madonna Into The Groove Madonna Holiday Madonna Border Line Madonna Lucky Star Madonna Ray of Light Meghan Trainor All About That Bass Michael Jackson Dirty Diana Michael Jackson Billie Jean Michael Jackson Human Nature Michael Jackson Black Or White Michael Jackson Bad Michael Jackson Wanna Be Startin’ Something Michael Jackson P.Y.T. -

Irreplaceable Lhand$Day$ Pg

DEALS OF THE $DAY$ PG. 3 THURSDAY, JULY 26, 2018 DEALS OF THE IRREPLACEABLE LHAND$DAY$ PG. 3 Beyoncé scholarship a big hit with Lynn girl dealt By Bella diGrazia of eight recipients of the Homecoming Scholars $1.15M ITEM STAFF Award for the 2018-2019 academic year, a merit DEALS program founded by Beyoncé as part of her Bey- LYNN — Most people never think they’re going GOOD campaign. On Monday, it was announced OF THE to meet their biggest idol, but Allana Bare eld by HUD did. And it didn’t end there. that Bare eld was chosen as the only student to $ $ represent her school, Xavier University, which is DAY The Lynn native and Lynn English gradu- By GaylaPG. 3Cawley ate (class of 2015) grew up idolizing Beyoncé located in New Orleans. ITEM STAFF Knowles. Last year, during an NBA All-Star “I woke up, just a typical day, trying to catch up party that Bare eld and her friends attended on my news and I get a noti cation from someone LYNN — Lynn Hous- last minute, she came face-to-face with the sing- congratulating me and I had no clue what was ing Authority & Neigh- er and thought her biggest dream was ful lled. borhood Development That was until she found out she was named one SCHOLARSHIP, A7 Beyonce (LHAND)DEALS has been awarded $1.15 million from theOF U.S. THE Department of Housing and Urban De- velopment$DA (HUD),Y$ which will fund aPG. four-year 3 pro- gram aimed at improving the quality of life of Cur- win Circle public housing residents. -

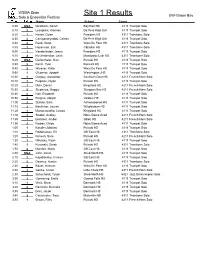

Site 1 Results

WSMA State Site 1 Results UW-Green Bay Solo & Ensemble Festival Name School Event 8:00DNA Mcallister, Sarah Bay Port HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 8:102 Lecaptain, Riannon De Pere High Sch 4111 Trumpet Solo 8:201 Kesler, Dylan Freedom HS 4311 Trombone Solo 8:302 Corriganreynolds, Cainen De Pere High Sch 4111 Trumpet Solo 8:402 Reeb, Noah West De Pere HS 4311 Trombone Solo 8:501 Hoyerman, Eric Gibraltar HS 4311 Trombone Solo 9:001 Vanderlinden, Jenna Freedom HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 9:102 Kuchenbecker, Leah Manitowoc Luth HS 4311 Trombone Solo 9:20DNA Diefenthaler, Nick Pulaski HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 9:302 Bonin, Tyler Roncalli HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 9:402 Wiesner, Katie West De Pere HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 9:501 O'connor, Joseph Washington JHS 4111 Trumpet Solo 10:001 Quigley, Alexander Southern Door HS 4211 French Horn Solo 10:101 Fulgione, Dylan Pulaski HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 10:201 Maki, Daniel Kingsford HS 4211 French Horn Solo 10:302 Stephens, Maggie Sturgeon Bay HS 4211 French Horn Solo 10:402 Hall, Elizabeth Pulaski HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 10:502 Reigles, Abigail Valders HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 11:00 2 Stanko, Sam Ashwaubenon HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 11:10 2 Boettcher, Lauren Wrightstown HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 11:20 1 Munoz-ozzello, Luiasa Kingsford HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 11:30 1 Sladek, Audrey Notre Dame Acad 4211 French Horn Solo 11:40 1 Brehmer, Amber Gillett HS 4211 French Horn Solo 11:50 2 Forbes, Chloe Notre Dame Acad 4111 Trumpet Solo 1:001 Kandler, Matheu Pulaski HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 1:101 Rodeheaver, Eli GB East HS 4311 Trombone Solo 1:201 Kunesh, Sara Pulaski -

Wesley Historical Society Editor: E

Proceedings OF THE Wesley Historical Society Editor: E. ALAN ROSE, B.A. Volume 56 February 2008 CHARLES WESLEY, 'WARTS AND ALL': The Evidence of the Prose Works The Wesley Historical Society Lecture 2007 Introduction ccording to his more famous brother John, Charles Wesley was a man of many talents of which the least was his ability to write A poetry.! This is a view with which few perhaps would today agree, for the writing of poetry, more specifically hymns, is the one thing above all others for which Charles Wesley has been remembered. Anecdotally I am sure that we all recognise that this is the case; and indeed if one were to look Charles up in more or less anyone of the many general biographical dictionaries that include an entry on him one will find it repeated often enough: Charles is portrayed as a poet and a hymn writer; while comparatively little, if any, attention is paid to other aspects of his work. On a more scholarly level too one can find it. Obviously there are exceptions, but in general historians of Methodism in particular and eighteenth-century Church history more widely have painted a picture of Charles that is all too monochrome and Charles' role as the 'Sweet Singer of Methodism' is as unquestioned as his broader significance is undeveloped. The reasons for this lack of full attention being paid to Charles are several and it is not (contrary to what is usually said) simply a matter of Charles being in his much more famous brother's shadow; a lesser light, as it were, belng outshone by a greater one.