The Fire Next Time”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

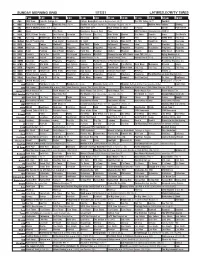

Sunday Morning Grid 1/17/21 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/17/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News College Basketball Iowa at Northwestern. (N) Å The NFL Today (N) Å Football 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å Hockey Washington Capitals at Pittsburgh Penguins. (N) Å Mecum Auto Auctions Skating 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Emeril Pain Relief! 7 ABC News This Week Eyewitness News at 9am News AKC National Championship 2020 Å 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Paid Prog. Mike Webb Harvest Sex Abuse Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Paid Prog. MAXX Oven Fox News Sunday The Issue News Sex Abuse AAA PiYo Paid Prog. MAXX Oven Paid Prog. 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch On Camera Rare 1899 Dr. Ho’s Caught on News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Smile Copper Workout! AAA New YOU! Smile Bathroom? Cleanse Ideal AAA Prostate Paid Prog. 2 2 KWHY Más Pelo Programa Resultados Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Resultados Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Queens Lidia Milk Street Field Trip 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ Memory Rescue With Daniel Amen, MD (TVG) Å Aging Backwards 3 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Amazing Hawaii Five-0 (TV14) Hawaii Five-0 (TV14) Hawaii Five-0 (TV14) Hawaii Five-0 (TV14) 3 4 KMEX Conexión Programa Programa Programa Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN R. -

'Perry Mason' Lays Down the Law Anew On

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! June 19 - 25, 2020 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 E A D T Y E A W A H P Y F A Z Your Key I J P E C L K S N Z R A E T C 2 x 3" ad To Buying R E Q I P L Y U G R P O U E Y Matthew Rhys stars P F L U J R H A E L Y N P L R and Selling! 2 x 3.5" ad F A R H O W E P L I T H G O W in “Perry Mason,” I F Y P N M A S E P Z X T J E premiering Sunday D E L L A Z R E S S E A M A G on HBO. Z P A R T R Y D L I G N S U S B F N Y H N E M H I O X L N N E R C H A L K D T J L N I A Y U R E L N X P S Y E Q G Y R F V T S R E D E M P T I O N H E E A Z P A V R J Z R W P E Y D M Y L U N L H Z O X A R Y S I A V E I F C I P W K R U V A H “Perry Mason” on HBO Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Perry (Mason) (Matthew) Rhys (Great) Depression Place your classified Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Della (Street) (Juliet) Rylance (Los) Angeles ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Paul (Drake) (Chris) Chalk Origins Midlothian Mirror and Ellis (Sister) Alice (Tatiana) Maslany (Private) Investigator County Trading1 Post! x 4" ad Deal Merchandise Word Search (E.B.) Jonathan (John) Lithgow Redemption Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 ‘Perry Mason’ lays down for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily2 x Light, 3.5" ad Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading Post and online at waxahachietx.com All specials are pre-paid. -

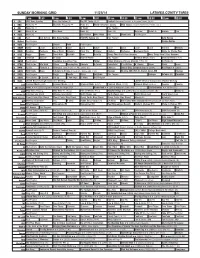

Sunday Morning Grid 11/23/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/23/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals at Houston Texans. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) World/Adventure Sports MLS Soccer: Eastern Conference Finals, Leg 1 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. Explore Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Paid Program Auto Racing 13 MyNet Paid Program Pirates-Worlds 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Monkey 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Barbecue Heirloom Meals Home for Christy Rost 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (9:50) (N) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio de Abu Dhabi. -

ALMA MATER STUDIORUM UNIVERSITA' DI BOLOGNA Corso Di

ALMA MATER STUDIORUM UNIVERSITA' DI BOLOGNA Corso di laurea magistrale in Cinema, Televisione e Produzione Multimediale Titolo della tesi La produzione di videoclip attraverso le sue trasformazioni economiche, sociali e distributive Tesi di laurea in Economia e Marketing dei Media Audiovisivi Relatore Presentata da Prof.ssa Veronica Innocenti Davide Ranni Correlatore Prof. Massimo Fantini Sessione I Anno Accademico 2020/2021 A Emma e Anna. Siate sempre coraggiose (∂ + m) ψ = 0 Indice Introduzione .................................................................................................................. 7 CAP. 1- L’EVOLUZIONE DEL VIDEOCLIP NELLA DISTRIBUZIONE ........ 13 1.1 Le età storiche del videoclip ............................................................................... 13 1.2. Da uno a due canali di comunicazione: dalla Tv a Youtube ........................... 28 1.2.1 La programmazione di MTV dal 1998 al 2020 ........................................... 29 1.2.2 L’Auditel e il videoclip ................................................................................. 37 1.2.3 I dati di ascolto televisivi di MTV Music e VH1 ......................................... 39 1.3 YouTube e il concetto di visualizzazioni ............................................................ 44 1.3.1 Il caso Vevo: il futuro del videoclip? ........................................................... 53 CAP. 2- I DIRITTI DEL VIDEOCLIP ..................................................................... 57 2.1 La legge sul diritto d’autore -

Våra Storsäljare! Ett Ännu Större Utbud Hittar Du På * A

Våra storsäljare! Ett ännu större utbud hittar du på www.ashild.se * A. Stretchtrosa. Bred spets- B. Från 3-PACK A. Från 229,- kant. Bra passform. Ger lite FRI FRAKT! stöd för mage. 95% bomull, 298,- 5% elastan. Tvätt 60°. Uppge erbjudandekod 26-1933 vit Stl. 38/40, 42/44 20B134A vid din 229,-/3-pack beställning! Stl. 46/48, 50/52 239,-/3-pack * Max 1 gång/kund när du handlar för 300,-. Stl. 54/56, 58/60 Gäller t.om 2020.12.12. Kan ej kombineras med 249,-/3-pack andra erbjudanden eller rabatter. B. Tunika. Vacker lätt ut- Extra erbjudande! ställd modell med krage och hel knäppning. Manschett- 0,- ärmar. Längden följer storle- ken ca 90-96 cm från axeln. Värde 249,- 100% polyester. Fintvätt 30°. 21-0304 svart/röd Stl. 38, 40, 42, 44 298,- 2-PACK Stl. 46, 48, 50, 52 318,- C. Från139,- Stl. 54, 56, 58 338,- C. Stretchtrosa. 95% bomull, 5% elastan. Tvätt 40°. 26-0813 vit/lilarosa Stl. 38/40, 42/44 139,-/2-pack Stl. 46/48, 50/52 149,-/2-pack Stl. 54/56, 58/60 159,-/2-pack D. Spetstrosa. Trosa med Sjal. 20-7258 0,- spetsinslag. Bra passform. 100% bomull. Tvätt 60°. Max 1/order - så långt lagret räcker! 26-0225 vit Stl. 38/40, 42/44 2-PACK D. Från 129,- 129,-/2-pack Reflexvante! Stl. 46/48, 50/52 Äkta 139,-/2-pack skinn Stl. 54/56 149,-/2-pack E. Reflexvante. Varm och skön med pilefoder. 80% ull, 20% polyamid. Handtvätt. En storlek. 20-0106 silver/svart 169,- F. -

Nyhet Från Viking of Norway! Garn Järbo Garn Alpaca Liten Storm 2 Tr Ull

För dig som älskar att sticka och virka! /paket FRI FRAKT * Din erbjudandekod 20B242K * Erbjudandet gäller max 1 gång/kund när du handlar för minst 300,- . Gäller t.o.m 2020-12-12. Kan inte kombineras med andra rabatter eller erbjudanden. Paket Grytlappar Julefrid! Virka ett par juliga grytlappar i garn Stina från Svarta Fåret! Kittet innehåller 4 nystan + beskrivning. Storlek: ca 25 cm i diameter. Kvalité: 100% kammad bomull.Tvättråd: 40° skontvätt. Köp till:Virknål 4mm. Art.nr: 08-0432 99,-/paket Art.nr: 37-4397 Virknål 4 mm 22,- Nyhet från Viking of Norway! Garn Järbo Garn Alpaca Liten Storm 2 tr Ull. Garn Alpaca Liten Storm från Viking of Norway Stickas lika fint på tunna stickor är lillebror till Garn Alpaca Storm och är till vantar som på grova stickor till ett mjukt aplackagarn som passar luftiga tröjor. Ullen i garnet är en perfekt till barn och babyplagg kvalitétsull som kommer från och andra lättare plagg. Nya Zeeland. Den är garanterat Nystan: 50 gram = 175 meter. mulesing-fri och ger ett mjukt Kvalité: 40% superfine alpaca, ullgarn. Kvalité: 100% mulesing- 40% merinoull och 20% nylon. fri ull. Härva: 100 g. = 300 m. Stickfasthet: 25 m =10 cm. Stickfasthet: 21 m x 30 v Rekommenderade stickor: 3 mm. = 10 x 10 cm. Tvättråd: 30° maskintvätt. Virkfasthet: 18 fm x 22 v = 10 x 10 cm. Se alla färger på knittingroom.se Rekommenderade stickor/virknål: 3,5 mm. Handtvätt. Se alla färger på knittingroom.se Kundtjänst tel. 033 - 16 99 50 Knittingroom, Box 923, 501 10 Borås. E-post: [email protected] Org.nr 556669-2082. -

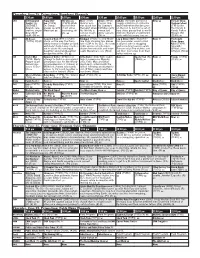

Thursday, June 25, Prime-Time: Broadcast Channels

Thursday, June 25, Prime-time: Broadcast Channels 7:30 pm 8:00 pm 8:30 pm 9:00 pm 9:30 pm 10:00 pm 10:30 pm 11:00 pm 11:30 pm CBS Entertainment Young Shel- The Unicorn Mom (TV14) Broke (TVPG) S.W.A.T. The team pursues a News Å The Late Show: Tonight The don (TVPG) (TVPG) Wade Bonnie wor- (Series fina- couple reminiscent of Bonnie Stephen Colbert 2020 BET Dr. Sturgis has his first ries about her le) Sammy’s and Clyde when the duo goes (TVPG) Au- Awards cele- breaks up with crush since therapist when birthday party on the run to hunt for a set of thor Ibram X. bration; singer Meemaw. Å becoming sin- his life hits a venue sud- rare chess pieces that is worth Kendi; Patton Brian McK- gle. Å serious rough denly cancels. millions; Darryl’s ex-girlfriend Oswalt. (N) night. (N) Å patch. Å (N) Å visits with his young son. Å (11:35) Å NBC All Access Council of Dads With a severe Blindspot (TV14) To stop Made- Law & Order: SVU (TV14) Roll- News Å The Tonight (TVPG) (N) Å storm on the way, the Perry line from shipping two planes ins goes under cover to find Show: Jimmy family heads for higher ground; full of ZIP to the U.S., the team a suspect who is drugging Fallon (TV14) with Luly’s help, Larry reaches splits up into a high-stakes and assaulting tourists, while Shaquille out to assist his estranged undercover mission and inter- Benson helps the victims sort O’Neal; John daughter and granddaughter cepts Madeline’s son. -

THE GIRLS of CAMP KOCH Fredericka A. Schmadel

GODDESS IN THE GREENWOOD: THE GIRLS OF CAMP KOCH Fredericka A. Schmadel Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology Indiana University May 2014 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee: ______________________________ John Holmes McDowell, PhD Chairperson ______________________________ Gregory Schrempp, PhD Member ______________________________ Hasan El-Shamy, PhD Member ______________________________ Henry Glassie, PhD Member January 24, 2014 ii Copyright © 2014 Fredericka A. Schmadel iii Dedicated to the Memory of Lou Froehle and Marion Woolcott With thanks and deep appreciation to Professors John Holmes McDowell, Hasan El- Shamy, Gregory Schrempp, Henry Glassie, Elizabeth Tucker, Jay Mechling, Hildegard Keller, and Linda Degh, who critiqued my work and encouraged me; And with endless gratitude to Donna Kopach, Karen Selby, Virginia Letsinger Hale, Anne Katherine, Ann Briel Weston, Cassandra Major, Sharon White, Judy Burns, David Coker, Peter Hare, Lori Meyers, Beth Heil, and the Kochies, who set me on the right path, again and again; And with endless appreciation to my parents, Earl and Martha Schmadel, who sent me to Girl Scout camp in 1958 and thereafter, and by doing so, opened my eyes and mind. iv Fredericka A. Schmadel GODDESS IN THE GREENWOOD: THE GIRLS OF CAMP KOCH Worldview, myth, and the 1960s come together in a song, ritual, and legend corpus preserved in oral transmission, central to an Indiana Girl Scout camp’s cultural production. As Levi-Strauss disciple Lee Drummond might describe it, Camp Henry F. -

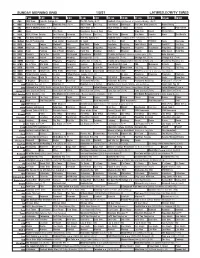

Sunday Morning Grid 1/3/21 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/3/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Cleveland Browns. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å NBC4 News Paid Prog. Pain Relief Bensinger The Chris Nikic Story (N) Alpine Skiing 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch AAA Pain Relief! 7 ABC News This Week Eyewitness News at 9am News Grow Hair Emeril 30 for 30 Å 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Paid Prog. Mike Webb Harvest Sex Abuse Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Dallas Cowboys at New York Giants. (N) Å 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Paid Prog. AAA Dr. Ho’s PROTECT News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Smile Copper Workout! AAA New YOU! Smile Transform Paid Prog. Paint Like A AAA WalkFit! Paid Prog. 2 2 KWHY Más Pelo Programa Más Pelo Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Resultados Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Queens Lidia Milk Street Field Trip 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ A Salute to Vienna A music and dance gala. -

Twelve of the Best: Volume 50 Flogmaster

Random Praise for the Flogmaster’s Writing I love this story. Especially how Brad helps Brittany become a better person. L.B.T. She did well to hold her own, although I’m sure he caused more damage than she did. At least guys know not to butt pinch her unless they’re willing to go to war for it. M.J.T. Oh wow! I never saw that coming. That was a true sucker punch, Flogmaster. B.O. I have read hundreds of these stories and this is my favourite. Short, concise, funny. C.J.H. A lovely story. V.C. Amazing style, original perspective, wonderful descriptions. M.C.Z. A masterpiece. Such a simple set up and expertly done. O.B. Selected Excerpts From At Billy’s: Amy moaned and bent over, reaching for her toes. Her bottom turned into a tight ball, her legs together with her pert globe above. Her mother swung the cane and hit those cheeks with a sharp snap that literally made my cock jump. It made Amy jump, too, but for a different reason. She yelped and a bright red line crossed her buttocks. She moaned. A second swish- crack added another line just below, and then a third followed. Amy began to weep. From French Class: I, being small, was able to slip up behind her unnoticed. I darted forward, grabbed the sides of her skirt, and yanked the whole thing downward. The skirt came off the slim hips and fell all the way to floor, tangling around her ankles. The girl’s butt in tiny panties that were almost thongs—scandalous back in those days—was right in my face. -

Call Your Mother “Fast Foodies” (Trutv — Series Premiere, Feb

Veteran sports writer Rick Noland reports on the January 8 - 14, 2021 CAFollow him in theVS sports pages of 2 x 4” ad A- House Ad B- Grizzly Auto infocus Call Your Mother “Fast Foodies” (truTV — series premiere, Feb. 4) “Top Chef” winners Kristen Kish, Jeremy Ford and “Iron Chef” winner Justin Sutherland compete to recreate and reimagine a celebrity Kyra Sedgwick stars in “Call Your Mother,” guest’s favorite fast food dish. Those making appearances include Joel McHale (“Community”), James Van Der Beek (“Bad Hair”), Andy Richter (“Conan”), Amanda Seales (“Insecure”), Ron Funches (“Top premiering Wednesday on ABC. Secret Videos”), Kevin Heffernan and Steve Lemme (“Tacoma FD”) and Charlotte McKinney (“Fantasy Island”). Medicare 30-day Window Plan ahead and play it safe! What happens when you or a loved one returns home from a hospital or Medicare-covered stay in a rehabilitation or skilled nursing facility, and you fi nd that you need additional care or recovery time? Maybe you developed a new illness or problem, or lost the ability to care for yourself. We have good news for you! Medicare regulations allow patients to be readmitted within a 30-day period, known as the Medicare window, without needing to be re-hospitalized. So what does this mean to you? Should you experience a decline during the next 30 days, you can return to Life Care Center of Medina for additional Medicare coverage. In coordination with your physician, we will readmit you under Medicare services. Contact our referral line today at Or Visit Us Online: 2400 Columbia -

Internet & Telephony Outage on June 23 JUNE EMPLOYEE SPOTLIGHT

Internet & Telephony Outage On June 23 CNSNext has a planned Internet and telephony outage scheduled for June 23 from approximately 12:01 AM - 7:00 AM in all cities. Customers will not experience service interruptions for the entire time period; however, interruptions of services are expected to occur intermittently throughout this time. The 2020 NASCAR Cup Series is in full swing! Your commercial spot can be seen during the following races: 6/28- Pocono 350 7/12- Quaker State 400 7/15- NASCAR All-star Race Contact Brandy at 229-227-4090 to update your advertising schedule today! JUNE EMPLOYEE SPOTLIGHT Meet Sarah Baggett! She is our CNSNext Marketing Manager. We sat down to learn a little bit more about her. How long have you worked for CNSNext? 6 years What does a typical work day consist of for you? One of the best parts of the job is that every day is different! Some of my day-to-day responsibilities include creating marketing plans and training team members on new product launches. What's your favorite part of working for CNSNext? Knowing that CNSNext offers the best quality products and customer service around. Our team really cares about each individual customer. CNSNext Customer Testimonial "Two years ago I made a decision to switch from CNSNext to Dish Network. I was soon unhappy but stuck with a two-year contract. It recently ended and I could not wait to return to CNSNext. Today, a fine young man by the name of Matt came out & installed our cable back. It is rare to find a lot of young adults with his manners and work ethics these days.