Criminal Libel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extent to Which the Common Law Is Applied in Determining What

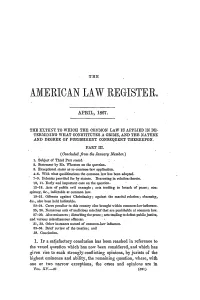

THE AMERICAN LAW REGISTER, APRIL, 1867. THE EXTE'N"IT TO WHICH THE COM ON LAW IS APPLIED IN DE- TERMINING WHAT CONSTITUTES A CRIME, AND THE NATURE AND DEGREE OF PUNISHMENT CONSEQUENT THEREUPON. PART III. (Concluded from the January.umber.) 1. Subject of Third. Part stated. 2. Statement by .Mr. Wheaton on tie question. 3. Exceptional states as to common-law application. 4-6. With what qualifications the common law has been adopted. 7-9. Felonies provided for by statute. Reasoning in relation thereto. 10, 11. Early and important case on the question. 12-18. Acts of public evil example; acts tending to breach of peace; con- -piracy, &c., indictable at common law. 19-21. Offences against Christianity; against the marital relation; obscenity, &c., also been held indictable. 22-24. Cases peculiar to this country also brought within common-law influence. 25, 26. 'Numerous acts of malicious mischief that are punishable at common law. 27-30. Also nuisances ; disturbing the peace; acts tenxding to defeat public justice. and various miscellaneous offences. 31, 32. Other instances named of common-law influence. 33-36. Brief review of the treatise; and 38. Conclusion. 1. IF a satisfactory conclusion has been reached in reference to the vexed question which has now been considered, and which has given rise to such strongly-conflicting opinions, by jurists of the highest eminence and ability, the remaining question, where, with one or two narrow exceptions, the eases and opinions are in VOL. XV.-21 (321) APPLICATION OF THE COMMON LAW almost perfect accord, cannot be attended with much difficulty. -

R V Adams (Appellant) (Northern Ireland)

Easter Term [2020] UKSC 19 On appeal from: [2018] NICA 8 JUDGMENT R v Adams (Appellant) (Northern Ireland) before Lord Kerr Lady Black Lord Lloyd-Jones Lord Kitchin Lord Burnett JUDGMENT GIVEN ON 13 May 2020 Heard on 19 November 2019 Appellant Respondent Sean Doran QC Tony McGleenan QC Donal Sayers BL Paul McLaughlin BL (Instructed by PJ McGrory (Instructed by Director of & Co Solicitors) Public Prosecutions, Public Prosecution Service) LORD KERR: (with whom Lady Black, Lord Lloyd-Jones, Lord Kitchin and Lord Burnett agree) Introduction 1. From 1922 successive items of legislation authorised the detention without trial of persons in Northern Ireland, a regime commonly known as internment. Internment was last introduced in that province on 9 August 1971. On that date and for some time following it, a large number of persons were detained. The way in which internment operated then was that initially an interim custody order (ICO) was made where the Secretary of State considered that an individual was involved in terrorism. On foot of the ICO that person was taken into custody. The person detained had to be released within 28 days unless the Chief Constable referred the matter to a commissioner. The detention continued while the commissioner considered the matter. If satisfied that the person was involved in terrorism, the commissioner would make a detention order. If not so satisfied, the release of the person detained would be ordered. 2. An ICO was made in respect of the appellant on 21 July 1973. The order was signed by a Minister of State in the Northern Ireland Office. -

Bill Digest: Thirty-Seventh Amendment of the Constitution

Bill Digest | Thirty-seventh Amendment of the Constitution-Blasphemy Bill 2018 1 Bill Digest Thirty-seventh Amendment of the Constitution (Repeal of offence of publication or utterance of blasphemous matter) Bill 2018 Bill No. 87 of 2018 Roni Buckley, Parliamentary Researcher (Law) Monday, 23 July 2018 Abstract The Thirty-seventh Amendment of the Constitution (Repeal of the offence of publication or utterance of blasphemous matter) Bill 2018 proposes the removal of the offence of blasphemy from the Constitution by way of referendum. Under the current framework the Constitution provides that the offence of blasphemy is punishable according to law. The Defamation Act 2009 defines the offence and provides that a person shall be liable upon conviction on indictment for a maximum fine of €25,000. This Digest sets out recent events and controversies relating to blasphemy; assesses its historical and legislative development as well as relevant case-law. Finally, the Digest provides a comparative analysis with European and international countries. Oireachtas Library & Research Service | Bill Digest 2 Contents Summary ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Proposed Amendment ................................................................................................................. 4 Definition of Blasphemy ............................................................................................................... 4 Reviews of the offence -

Submission to the 91St Session of the United Nations Human Rights Committee

Submission to the 91st Session of the United Nations Human Rights Committee on Respect for Freedom of Expression in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland London October 2007 ARTICLE 19 à 6-8 Amwell Street à London EC1R 1UQ à United Kingdom Tel +44 20 7278 9292 à Fax +44 20 7278 7660 à [email protected] à http://www.article19.org 1. Introduction This submission outlines ARTICLE 19’s main concerns regarding respect for the right to freedom of expression in the United Kingdom. Our submissions is presented in respect of the consideration by the United Nations Human Rights Committee of the Sixth Periodic Report of the United Kingdom on the implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). A list of possible questions to be posed to the United Kingdom representation is appended to this submission. ARTICLE 19 is an international, non-governmental human rights organisation which works around the world to protect and promote the right to freedom of expression and information. 2. Summary of concerns The United Kingdom is a long-standing member of the Council of Europe and European Union and a party to the European Convention of Human Rights as well as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. While the right to freedom of expression is generally respected, there are currently problems in five key areas: Access to information: i) The Freedom of Information Act 2000 contains exemptions which allow access to information to be refused on arbitrary or inappropriate grounds. ii) The government has proposed FOIA amendments to the way the costs of processing a request under the Act are assessed, making it easier to reject politically sensitive or complex requests on the grounds of costs. -

Jeremy Lynn YEAR of CALL: 1983

Jeremy Lynn YEAR OF CALL: 1983 EXPERTISE Jeremy has been practising in Criminal Law for 35 years. His experience of Crime is second-to-none. In cases of murder, Jeremy has successfully defended as a junior alone, but also as a leading junior. He is happy to be led in such cases and has recently established a successful partnership with Martin Rutherford QC in cases of murder and rape. In their most recent case together Jeremy and Martin secured the acquittal of a Cambridge student charged with the rape of another student he met online. Jeremy has enormous experience of defending in sex cases, including historic offences and those in- volving vulnerable witnesses. He has a particular interest in cases involving computer and social-media evidence, and has unpar- alled experience in the field of indecent images. In that regard he is regularly instructed by Lewis Nedas & Co. themselves experts in the field. In one case in 2018 their client, head of IT at an NHS health trust, was acquitted when Jeremy launched an abuse of process argument. The CPS were or- dered to pay £12,000 in wasted costs. Recent successes have included the trial of a woman charged with allowing her own daughter to be sold for sex at dogging-sites; a man charged with raping a woman he met through a massage site on Facebook; a professional masseur charged with sexually assaulting two patients; a young school mas- ter accused of raping his former girlfriend over an 18 month period; a 19 year old man charged with raping a 15 year old girl, the act having been filmed by his friend; and a 14 year old boy charged with raping 5 girls at school. -

Criminal Code 2003.Pmd 273 11/27/2004, 12:35 PM 274 No

273 No. 9 ] Criminal Code [2004. SAINT LUCIA ______ No. 9 of 2004 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS CHAPTER ONE General Provisions PART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title 2. Commencement 3. Application of Code 4. General construction of Code 5. Common law procedure to apply where necessary 6. Interpretation PART II JUSTIFICATIONS AND EXCUSES 7. Claim of right 8. Consent by deceit or duress void 9. Consent void by incapacity 10. Consent by mistake of fact 11. Consent by exercise of undue authority 12. Consent by person in authority not given in good faith 13. Exercise of authority 14. Explanation of authority 15. Invalid consent not prejudicial 16. Extent of justification 17. Consent to fight cannot justify harm 18. Consent to killing unjustifiable 19. Consent to harm or wound 20. Medical or surgical treatment must be proper 21. Medical or surgical or other force to minors or others in custody 22. Use of force, where person unable to consent 23. Revocation annuls consent 24. Ignorance or mistake of fact criminal code 2003.pmd 273 11/27/2004, 12:35 PM 274 No. 9 ] Criminal Code [2004. 25. Ignorance of law no excuse 26. Age of criminal responsibility 27. Presumption of mental disorder 28. Intoxication, when an excuse 29. Aider may justify same force as person aided 30. Arrest with or without process for crime 31. Arrest, etc., other than for indictable offence 32. Bona fide assistant and correctional officer 33. Bona fide execution of defective warrant or process 34. Reasonable use of force in self-defence 35. Defence of property, possession of right 36. -

The Way in Which Large Organisations Conduct Private Prosecutions; RSPCA

JUSTICE COMMITTEE, PRIVATE PROSECUTIONS BY ORGANISATONS BY MS.P. WALLWORK The way in which large organisations conduct private prosecutions; RSPCA Navigating the submission. Submission summary in bullet points page 2 POINT NUMBERS BELOW The RSPCA in a prosecution role, with the reasons it should not continue 1 – 36 Lawfulness of any RSPCA prosecution? 6 – 36 Role of the police, 37 – 43 Role of the RSPCA 44 – 85 A. Charitable status 44 -46 B. Prosecution lack of legal oversight 47 – 49 C. Crown Prosecution Service not involved 50 – 68 D. Lack of oversight by the courts 69 – 85 RSPCA double standards 86 – 91 RSPCA without police present and where police do not have a warrant 92 -105 RSPCA witness statements 106 – 115 RSPCA and the Courts 116 – 122 RSPCA and the legal profession 123 –125 RSPCA and the cost to the charity of a prosecution policy 126 – 129 Cost to the public from an RSPCA prosecution 130 – 135 RSPCA relationship with local authorities 136 – 144 Benefit to animal welfare 145 – 147 Cost to local authorities of implementing section 51 inspectors 148 -162 Proposals - page 30 Additional material in support of points made in the body of the submission Twenty ways to have your animals taken unlawfully page 32 RSPCA recruitment – demonstrating that ‘inspector’ level employees are unqualified to inspect animals. (Direct from RSPCA ) page 33. Wooler report page 35 RSPCA, firearms, and killing animals page 40 CASE FILES PAGE 44 - 57 end off submission. 1 JUSTICE COMMITTEE, PRIVATE PROSECUTIONS BY ORGANISATONS BY MS.P. WALLWORK The author of this submission. The writer of this document re ‘private prosecutions’ by organisations has been researching the subject of the RSPCA since 2015, including many cases in depth, having graduated with a law degree, completed examinations to become a solicitor, and lectured within a university setting to law undergraduates. -

Defamation in Scotland and the Republic of Ireland

Research and Information Service Briefing Paper Paper 37/14 21 March 2014 NIAR 95-14 Michael Potter Defamation in Scotland and the Republic of Ireland Nothing in this paper constitutes legal advice or should be used as a replacement for such 1 Introduction The Committee for Finance and Personnel commissioned background research into the approaches adopted by the Scottish Parliament and the Oireachtas with respect to defamation law1. This paper supplements Briefing Paper 90/13 ‘The Defamation Act 2013’2, presented to the Committee for Finance and Personnel on 26 June 20133. The paper considers defamation law in Scotland and the Republic of Ireland in the light of legislative change in England and Wales brought about by the Defamation Act 2013. 1 Meeting of the Committee for Finance and Personnel 3 July 2013: http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/Documents/Finance/minutes/20130703.pdf. 2 Research and Information Service Briefing Paper 90/13 The Defamation Act 2013 21 June 2013: http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/Documents/RaISe/Publications/2013/finance_personnel/9013.pdf. 3 Meeting of the Committee for Finance and Personnel 26 June 2013: http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/Documents/Finance/minutes/20130626.pdf. Providing research and information services to the Northern Ireland Assembly 1 NIAR 95-14 Briefing Paper 2 Defamation Law in England and Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland The basis of defamation law in all four jurisdictions is in common law. Legislation has codified certain aspects of defamation in each case, the more recent -

Going Public: How the Government Assumed the Authority to Prosecute in the Southern United States

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects January 2016 Going Public: How The Government Assumed The Authority To Prosecute In The outheS rn United States Jason Twede Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Twede, Jason, "Going Public: How The Government Assumed The Authority To Prosecute In The outheS rn United States" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1975. https://commons.und.edu/theses/1975 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOING PUBLIC: HOW THE GOVERNMENT ASSUMED THE AUTHORITY TO PROSECUTE IN THE SOUTHERN UNITED STATES by Jason Allan Twede Bachelor of Arts, Weber State University, 2003 Juris Doctor, Thomas M. Cooley Law School, 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Grand Forks, North Dakota May 2016 PERMISSION Title Going Public: How the Government Assumed the Authority to Prosecute in the Southern United States Department Criminal Justice Degree Doctor of Philosophy In presenting this dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the library of this University shall make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for extensive copying for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor who supervised my dissertation work or, in his absence, by the Chairperson of the department or the dean of the School of Graduate Studies. -

Marshall Islands Consolidated Legislation

Criminal Code [31 MIRC Ch 1] http://www.paclii.org/mh/legis/consol_act/cc94/ Home | Databases | WorldLII | Search | Feedback Marshall Islands Consolidated Legislation You are here: PacLII >> Databases >> Marshall Islands Consolidated Legislation >> Criminal Code [31 MIRC Ch 1] Database Search | Name Search | Noteup | Download | Help Criminal Code [31 MIRC Ch 1] 31 MIRC Ch 1 MARSHALL ISLANDS REVISED CODE 2004 TITLE 31. - CRIMES AND PUNISHMENTS CHAPTER 1. CRIMINAL CODE ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section PART I - GENERAL PROVISIONS §101 . Short title. §102 . Classification of crimes. §103. Definitions, Burden of Proof; General principles of liability; Requirements of culpability. §104 . Accessories. §105 . Attempts. §106 . Insanity. §107 . Presumption as to responsibility of children. §108 . Limitation of prosecution. §109. Limitation of punishment for crimes in violation of native customs. PART II - ABUSE OF PROCESS §110 . Interference with service of process. §111 .Concealment, removal or alteration of record or process. PART III - ARSON §112 . Defined; punishment. PART IV - ASSAULT AND BATTERY §113 . Assault. §114 . Aggravated assault. §115 . Assault and battery. §116 . Assault and battery with a dangerous weapon. 1 of 37 25/08/2011 14:51 Criminal Code [31 MIRC Ch 1] http://www.paclii.org/mh/legis/consol_act/cc94/ PART V - BIGAMY §117 . Defined; punishment. PART VI - BRIBERY §118 . Defined; punishment. PART VII - BURGLARY §119. Defined; punishment. PART VIII - CONSPIRACY §120 . Defined, punishment. PART IX – COUNTERFEITING §121 . Defined; punishment. PART X - DISTURBANCES, RIOTS, AND OTHER CRIMES AGAINST THE PEACE §122 . Disturbing the peace. §123 . Riot. §124. Drunken and disorderly conduct. §125 . Affray. §126 . Security to keep the peace. PART XI - ESCAPE AND RESCUE §127. Escape. -

Abolishing the Crime of Public Nuisance and Modernising That of Public Indecency

International Law Research; Vol. 6, No. 1; 2017 ISSN 1927-5234 E-ISSN 1927-5242 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Abolishing the Crime of Public Nuisance and Modernising That of Public Indecency Graham McBain1,2 1 Peterhouse, Cambridge, UK 2 Harvard Law School, USA Correspondence: Graham McBain, 21 Millmead Terrace, Guildford, Surrey GU2 4AT, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Received: November 20, 2016 Accepted: February 19, 2017 Online Published: March 7, 2017 doi:10.5539/ilr.v6n1p1 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ilr.v6n1p1 1. INTRODUCTION Prior articles have asserted that English criminal law is very fragmented and that a considerable amount of the older law - especially the common law - is badly out of date.1 The purpose of this article is to consider the crime of public nuisance (also called common nuisance), a common law crime. The word 'nuisance' derives from the old french 'nuisance' or 'nusance' 2 and the latin, nocumentum.3 The basic meaning of the word is that of 'annoyance';4 In medieval English, the word 'common' comes from the word 'commune' which, itself, derives from the latin 'communa' - being a commonality, a group of people, a corporation.5 In 1191, the City of London (the 'City') became a commune. Thereafter, it is usual to find references with that term - such as common carrier, common highway, common council, common scold, common prostitute etc;6 The reference to 'common' designated things available to the general public as opposed to the individual. For example, the common carrier, common farrier and common innkeeper exercised a public employment and not just a private one. -

Choctaw Nation Criminal Code

Choctaw Nation Criminal Code Table of Contents Part I. In General ........................................................................................................................ 38 Chapter 1. Preliminary Provisions ............................................................................................ 38 Section 1. Title of code ............................................................................................................. 38 Section 2. Criminal acts are only those prescribed ................................................................... 38 Section 3. Crime and public offense defined ............................................................................ 38 Section 4. Crimes classified ...................................................................................................... 38 Section 5. Felony defined .......................................................................................................... 39 Section 6. Misdemeanor defined ............................................................................................... 39 Section 7. Objects of criminal code .......................................................................................... 39 Section 8. Conviction must precede punishment ...................................................................... 39 Section 9. Punishment of felonies ............................................................................................. 39 Section 10. Punishment of misdemeanor .................................................................................