Jbottar of I^Ljilosiopljp in ENGLISH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entombed - Hollowman Mp3 Download

Entombed - Hollowman mp3 download DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Performer: Entombed Album: Hollowman Country: UK Released: 2014 Style: Death Metal MP3 version RAR size: 1403 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1687 mb WMA version RAR size: 1107 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 422 Other Formats: VOC MPC MIDI MP2 AA DXD AUD MP3 album Entombed - Hollowman download description Tracklist Hide Credits A1 Hollowman 4:29 A2 Serpent Speech 2:08 Wolverine Blues A3 2:12 Music By – Cederlund* Bonehouse B1 3:35 Lyrics By – Håkansson*, Cederlund* Put Off The Scent B2 3:15 Lyrics By – Hellid* Hellraiser B3 5:40 Arranged By – Entombed, Andersson*Music By – Christopher Young Companies, etc. Recorded At – Sunlight Studios Credits Artwork – Alex Hellid, Dick Håkansson Bass – Lars Rosenberg Drums – Nicke Andersson Guitar – Alex Hellid, Ulf Cederlund Lyrics By – Andersson* (tracks: A1, A2) Music By – Andersson* (tracks: A1 to B2) Producer – Entombed, Tomas Skogsberg Vocals – Lars-Göran Petrov Notes Recorded at Sunlight Studios Stockholm, 1992/1993. Pressed from original tapes in Full Dynamic Range (FDR) Audio-Sound. Available colours: - "Bonehouse White" (100 copies) - red / yellow "Hellraiser Splatter" (200 copies; this one) - green / black-splattered "Serpent Speech" (300 copies) - black (400 copies) Contains a poster. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 5 055006 509489 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year UK & MOSH 94 T Entombed Hollowman (12", EP) Earache MOSH 94 T 1993 Europe Hollowman (Cass, CT57504 Entombed Earache CT57504 US 1993 S/Sided) Hollowman (CD, EP, MOSH 94 Entombed Earache MOSH 94 US 1996 RE) Hollowman (CD, EP, MOSH 94 Entombed Earache MOSH 94 UK 1996 RE) CK 57504, Columbia, CK 57504, Entombed Hollowman (CD, EP) US 1993 57504 Columbia 57504 Related MP3 albums to Hollowman Entombed 1. -

Beck Reverend Horton Heat Mc 900 Ft

GPO BECK One Foot In The Grave •K REVEREND HORTON HEAT Liquor In The Front • Sub Pop-lnterscope MC 900 FT JESUS One Step Ahead Of The Spider •american FIFTH COLUMN 36C •K VMJ! SOUNDGARDEN SURE THING! aRnivu CX LIGPT RIDE SPONTANEOUS COMBUSTION Your shirt will stink for weeks Recorded Live At CBGB 12-19-1993 Glamorous • Deaf As A Bat • Sea Sick • Bloody Mary • Mistletoe • Nub Elegy • Killer McHann • Dancing Naked Ladies • Fly On The Wall Boilermaker • Puss • Gladiator • Wheelchair Epidemic • Monkey Trick Fifteen tracks of teeth-loosening madness. CD. Cassette. Limited Edition Vinyl. gtdllt pace 3... Johnn Rebel Redeemed ash First of all, what everyone wants to know about a long-dis- tance interview with Johnny Cash: No, he didn't answer the phone and say "Hello—I'm Johnny Cash." Still, it is a little disconcerting at first, hearing that low ominous voice over the telephone, speaking from his Tennessee cabin, discussing the weather or reading off the address for his House Of Cash management office. "This is on album I've always wanted to do," he says of American Recordings. "I even had a name 25 years ago for this album, it was going to be called Johnny Cash Alone. Years later Ithought about it again and wanted to do an album like this, and call it Johnny Cash Up Close. But this same concept has been in my mind since the early '70s." About his first meeting with producer/label head Rick Rubin, Cash recalls, "I liked the way he talked. Because right off he said, 'I'm familiar with most of your work, and you know what you do best. -

Read Book Entombed Ebook, Epub

ENTOMBED PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Linda Fairstein | 503 pages | 01 Feb 2006 | Pocket Star Books | 9780743482271 | English | New York, NY, United States Entombed | Discography | Discogs With the presence of cracking within the surviving fragments the possibility of any organic compounds entombed within the pre-impact meteoroid escaping and mixing with the surrounding environment are increased. To start with, it is not even clear exactly what sort of tree produced the fluid resins that subsequently hardened about their entombed captives to form the amber. In its magnificent library there are entombed unprinted manuscripts of the most valuable and important kind. Thirteen are still entombed , and every effort to find them has so far failed. The consequence would be that hundreds of men would be entombed without any possibility of being saved. They are entombed in the urns and sepulchres of mortality. The men heard it coming but had not time to get to the top or bottom gateway, and were temporarily entombed. Secondly, the concrete casing of the entombed reactor is unsafe and unstable. I stood with a group of people a few months ago in the yard of a great colliery, where over eighty men were entombed and ultimately lost their lives. I was certain that he had painted himself into a corner, and that he would soon find himself not so much painted into that corner as entombed in it. October 18, Sign up for free and get access to exclusive content:. Free word lists and quizzes from Cambridge. Favorite Artists by Antithetical. Death Metal by Kein. Seen live by Myrkrarfar. -

Cassette Catalog - Pdf Edition

arvard Square Records, Inc. P.O. Box 381975, Cambridge, MA 02238 Year 2001 Rare And Out Of Print CASSETTE CATALOG - PDF EDITION •Order Toll Free:1-877-465-7669 (GOLPNOW) •Customer Service:(617) 868-3385 •Fax: (617) 547-2838 • Email: [email protected] For vinyl please contact us, or visit our website LPnow.com arvard Square Records, Inc. P.O. Box 381975, Cambridge, MA 02238 Year 2001 Rare And Out Of Print CASSETTE CATALOG - PDF EDITION •Order Toll Free:1-877-465-7669 (GOLPNOW) •Customer Service:(617) 868-3385 •Fax: (617) 547-2838 • Email: [email protected] For vinyl please contact us, or visit our website LPnow.com Special Note on Reserving Stock and Song Titles: Customer Info We do not reserve any stock nor do we have the song titles of any title available to us. Please do not call or email to see if something is in stock or Please read this before calling with questions. what songs are on any title. Everything in this catalog is available to us at press time, but we cannot guarantee the availability of any title on the HI! HI! phone. Placing an order is the best and fastest way to insure you get the Welcome to our year 2001 Sealed Cassette Catalog. titles you want. Orders begin only when payment or credit card # is received. We had no 1999/2000 Cassette catalog (sorry) so this is our 1st cassette The sooner you order, the sooner you will get your order. catalog since our 1998 one, which is now void. This catalog will be good We have many sources for most of the titles listed, but some titles have no until the end of 2001. -

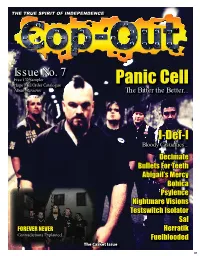

Cop out Magazine 07 – Web Version

TTHEHE TRUETRUE SPIRITSPIRIT OFOF INDEPENDENCEINDEPENDENCE IIssuessue No.No. 7 FFreeree CCDD SSamplerampler PPanicanic CCellell HHugeuge MMailail OOrderrder CCatalogueatalogue AAlbumlbum RReviewseviews TThehe BBitteritter tthehe BBetter...etter... II-Def-I-Def-I BBloodyloody CCasualties...asualties... DDecimateecimate BBulletsullets ForFor TeethTeeth AAbigail’sbigail’s MMercyercy BBohicaohica PPsylencesylence NNightmareightmare VVisionsisions TTestswitchestswitch IIsolatorsolator SSalal FFOREVEROREVER NNEVEREVER HHerratikerratik CContradictionsontradictions EExplained...xplained... FFuelbloodeduelblooded TThehe CCasketasket IssueIssue 01 02 CCOP-OUTOP-OUT #7#7 IIss bboughtought ttoo yyouou withwith thhee hhelpelp aandnd aassistences of the following people. Welcome To Cop-Out 07 sistence of the following people. HHelloello andand welcomewelcome toto anotheranother instalmentinstalment ofof Cop-Out,Cop-Out, thethe underfunded,underfunded, badlybadly writtenwritten andand cclobberedlobbered togethertogether catazinecatazine fromfrom thosethose jokersjokers atat CoproCopro Towers.Towers. SomeSome ofof youyou willwill bebe sur-sur- EEDITORDITOR JJoseose GGrifriffi n pprisedrised toto fi nnallyally havehave anotheranother oneone ofof thesethese fallfall onon youryour doordoor mat,mat, somesome ofof you,you, willwill bebe wonder-wonder- [email protected]@coproreords.co.uk iingng jjustust wwhathat tthehe hellhell thisthis is,is, butbut hopefullyhopefully allall ofof you,you, oror atat thethe veryvery leastleast mostmost ofof you,you, -

Entombed Left Hand Path Mp3, Flac, Wma

Entombed Left Hand Path mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Left Hand Path Country: UK, Europe & US Style: Death Metal MP3 version RAR size: 1350 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1467 mb WMA version RAR size: 1595 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 689 Other Formats: VQF MP2 MPC APE FLAC AUD MMF Tracklist Hide Credits Left Hand Path 1 Composed By [Contains Original "Phantasm" Theme, Uncredited] – Fred Myrow, Malcolm 6:38 Seagrave 2 Drowned 4:01 3 Revel In Flesh 3:43 4 When Life Has Ceased 4:11 5 Supposed To Rot 2:03 6 But Life Goes On 2:59 7 Bitter Loss 4:22 8 Morbid Devourment 5:25 9 Abnormally Deceased 2:58 10 The Truth Beyond 3:25 11 Carnal Leftovers 2:58 12 Premature Autopsy 4:25 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Earache Records Copyright (c) – Earache Records Published By – Earache Songs U.K. Recorded At – Sunlight Studios Mixed At – Sunlight Studios Distributed By – Revolver Distributed By – The Cartel Distributed By – Rough Trade Distribution Distributed By – Revolver USA Credits Arranged By – Entombed, Nihilist Artwork [Cover Art] – Dan SeaGrave Artwork [Logo] – Nicke* Design – David Windmill Drums, Bass – Nicke Andersson Engineer – Tomas Skogsberg Guitar – Alex Hellid Guitar, Bass – Uffe Cederlund* Lyrics By – Alex*, Nicke* Music By – Leffe*, Nicke*, Uffe* Photography By – Micke Lundstrom Producer – Entombed, Tomas Skogsberg Songwriter – Entombed Vocals – Lars-Göran Petrov Notes Early identical repress - the only difference is the presence of a Mastering IFPI code. No Mould SID code Recorded and mixed at Sunlight Studio, Stockholm, December, 1989. Tracks 11 + 12 are Bonus Tracks.