Exposing Social Values Through Satire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written By

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written by Sam Catlin, Vince Gilligan, Peter Gould, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Moira Walley-Beckett; AMC The Good Wife, Written by Meredith Averill, Leonard Dick, Keith Eisner, Jacqueline Hoyt, Ted Humphrey, Michelle King, Robert King, Erica Shelton Kodish, Matthew Montoya, J.C. Nolan, Luke Schelhaas, Nichelle Tramble Spellman, Craig Turk, Julie Wolfe; CBS Homeland, Written by Henry Bromell, William E. Bromell, Alexander Cary, Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Barbara Hall, Patrick Harbinson, Chip Johannessen, Meredith Stiehm, Charlotte Stoudt, James Yoshimura; Showtime House Of Cards, Written by Kate Barnow, Rick Cleveland, Sam R. Forman, Gina Gionfriddo, Keith Huff, Sarah Treem, Beau Willimon; Netflix Mad Men, Written by Lisa Albert, Semi Chellas, Jason Grote, Jonathan Igla, Andre Jacquemetton, Maria Jacquemetton, Janet Leahy, Erin Levy, Michael Saltzman, Tom Smuts, Matthew Weiner, Carly Wray; AMC COMEDY SERIES 30 Rock, Written by Jack Burditt, Robert Carlock, Tom Ceraulo, Luke Del Tredici, Tina Fey, Lang Fisher, Matt Hubbard, Colleen McGuinness, Sam Means, Dylan Morgan, Nina Pedrad, Josh Siegal, Tracey Wigfield; NBC Modern Family, Written by Paul Corrigan, Bianca Douglas, Megan Ganz, Abraham Higginbotham, Ben Karlin, Elaine Ko, Steven Levitan, Christopher Lloyd, Dan O’Shannon, Jeffrey Richman, Audra Sielaff, Emily Spivey, Brad Walsh, Bill Wrubel, Danny Zuker; ABC Parks And Recreation, Written by Megan Amram, Donick Cary, Greg Daniels, Nate DiMeo, Emma Fletcher, Rachna -

Spring 2008 Volume 109, Number 1 WISCONSIN

Spring 2008 Volume 109, Number 1 WISCONSIN Reluctant Star 18 The UW scientist who first brought stem cells into the scientific spotlight — a discovery that sparked a volatile debate of political and medical ethics — doesn’t seek fame for himself. So when you are the go-to guy for everybody who wants access to James Thomson, a man who’d much rather be in the lab than in the media’s glare, you learn to say no more often than you’d like. By Terry Devitt ’78, MA’85 Seriously Funny 22 Some thought that Ben Karlin ’93 was walking away from success when he left his job as executive producer for TV’s The Daily 18 Show and The Colbert Report. But, as he explains in this conversation with On Wisconsin, he was simply charting a comedic path that includes a new book and his own production company. By Jenny Price ’96 Can of Worms 28 Graduate students have more to worry about than grades — there’s also research, funding, and, as the students working in one lab discovered, their mentor’s ethics. While PhD candidate Amy Hubert x’08 aims to overcome scandal and put the finishing touches on her degree, the UW struggles to protect the students who will create the future of science. 22 By John Allen INSIDE Campus on $5 a Day LETTERS 4 34 If a bill featuring Abe’s face is burning a hole in your pocket, SIFTING & WINNOWING 9 you’d be amazed to learn what it can buy on campus. Don some comfort- DISPATCHES 10 able shoes and discover what you can eat, see, and do at bargain prices. -

Televi and G 2013 Sion, Ne Graphic T 3 Writer Ews, Rad

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 6, 2012 2013 WRITERS GUILD AWARDDS TELEVISION, NEWS, RADIO, PROMOTIONAL WRITING, AND GRAPHIC ANIMATION NOMINEES ANNOUNCED Los Angeles and New York – The Writers Guild of Ameerica, West (WGAW) and the Writers Guild of America, East (WGAE) have announced nominaations for outstanding achievement in television, news, radio, promotional writing, and graphic animation during the 2012 season. The winners will be honored at the 2013 Writers Guild Awards on Sunday, February 17, 2013, at simultaneous ceremonies in Los Angeles and New York. TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Boardwalk Empire, Written by Dave Flebotte, Diane Frolov, Chris Haddock, Rolin Jones, Howard Korder, Steve Kornacki, Andrew Schneider, David Stenn, Terence Winter; HBO Breaking Bad, Written by Sam Catlin, Vince Gilligan, Peter Gouldd, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Moira Walley-Becckett; AMC Game of Thrones, Written by David Benioff, Bryan Cogman, George R. R. Martin, Vanessa Taylor, D.B. Weiss; HBO Homeland, Written by Henry Bromell, Alexander Cary, Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Chip Johannessen, Meredith Stiehm; Showtime Mad Men, Written by Lisa Albert, Semi Chellas, Jason Grote, Jonathan Igla, Andre Jacquemetton, Maria Jacquemetton, Brett Johnson, Janeet Leahy, Victor Levin, Erin Levy, Frank Pierson, Michael Saltzman, Tom Smuts, Matthew Weiner; AMC -more- 2013 Writers Guild Awards – TV-News-Radio-Promo Nominees Announced – Page 2 of 7 COMEDY SERIES 30 Rock, Written by Jack Burditt, Kay Cannon, Robert Carlock, Tom Ceraulo, Vali -

Don Martin Dies, Maddest of Mad Magazine Cartoonists

The Miami Herald January 8, 2000 Saturday DON MARTIN DIES, MADDEST OF MAD MAGAZINE CARTOONISTS BY DANIEL de VISE AND JASMINE KRIPALANI Don Martin was the man who put the Mad in Mad magazine. He drew edgy cartoons about hapless goofs with anvil jaws and hinged feet who usually met violent fates, sometimes with a nerve-shredding SHTOINK! His absurdist vignettes inspired two or three generations of rebellious teenage boys to hoard dog-eared Mads in closets and beneath beds. He was their secret. Martin died Thursday at Baptist Hospital after battling cancer at his South Dade home. He was 68. Colleagues considered him a genius in the same rank as Robert Crumb (Keep on Truckin') and Gary Larson (The Far Side). But adults seldom saw his work. And Don Martin's slack-jawed goofballs weren't about to pop up on calendars or mugs. The son of a New Jersey school supply salesman, Martin joined the fledgling Mad magazine in 1956 and stayed with the irreverent publication for 31 years. Editors billed him as "Mad's Maddest Cartoonist." "He was a hard-edged Charles Schulz," said Nick Meglin, co-editor of Mad. "It's no surprise that Snoopy got to the moon. And it's no surprise that Don Martin characters would wind up on the wall in some coffeehouse in San Francisco." COUNTERCULTURE HERO If Peanuts was the cartoon of mainstream America - embraced even by Apollo astronauts - then Martin's crazy-haired, oval-nosed boobs were heroes of the counterculture. Gilbert Shelton, an underground cartoonist who penned the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, said Martin was the reason he first picked up the pencil. -

I ABBREVIATIONS

SPECIAL SUMMER TRAVEL ISSUE • I ftr«*; '-^iisI I 'i N •' A / t? \ **4 '"'•mawmmiw :LLY FREAS -^ Even this much can cause plenty trouble Mainly for us! If you think carbon makes Gulp is all we can say when we think trouble for You, just wait till you see of how profits will shrink. Because just how much trouble this tiny little bit of this much will run your car for a year! fissionable material will make for Us! GULP SAYS THE OIL CORPORATIONS Gasoline Companies Against Nuclear Fuels NUMBER 65 SEPTEMBER 1961 VITAL FEATURES REALISTIC CHILDREN'S BOOKS 4 Our satire of those basic definitions in children's books (i.e. "A hole is to dig!") will convince you "A MAD is to throw out!" "Some people are like blisters, they show up right after the work is done!" —Alfred E. Neuman TV FOR LATE, LATE AUDIENCES 14 PUBLISHER: William M. Gaines EDITOR: Albert B. Feldstein The best TV can be seen from 2 to 6 A.M., mainly ART DIRECTOR: John Putnam PRODUCTION: Leonard Brenner because there's nothing EDITORIAL ASSOCIATES: Jerry De Fuccio, Nick Meglin on! However, here's what LAWSUITS: Martin J. Scheiman PROPAGANDA MINISTER: Larry Gore can be done to fix that! SUBSCRIPTIONS: Gloria Orlando, Celia Morelli, Anthony Giordano CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS AND WRITERS: The Usual Gang of Idiots A MAD LOOK AT THE BEACH 18 You won't starve on the beach because of "sand- DEPARTMENTS which-is" there, but you BRAND X MARKS THE SPOT DEPARTMENT can die laughing because TV Commercials With Suspense 28 of clods which are there. -

JUDGE of BEAUTY Estate of the Honorable Paul H

STEPHEN GEPPI DIXIE CARTER SANDY KOUFAX MAGAZINE FOR THE INTELLIGENT COLLECTOR SPRing 2009 $9.95 JUDGE OF BEAUTY Estate of the Honorable Paul H. Buchanan Jr. includes works by landmark figures in the canon of American Art CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS JUDGE OF BEAUTY Estate of the Honorable Paul H. 30 Buchanan Jr. includes works by landmark figures in the canon of American art SUPER COLLectoR A relentless passion for classic American 42 pop culture has turned Stephen Geppi into one of the world’s top collectors IT’S A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad (MagaZINE) WORLD 50 Demand for original cover art reflects iconic status of humor magazine SIX THINgs I LeaRNed FRom WARREN Buffett 56 Using the legendary investor’s secrets of success in today’s rare-coins market IN EVERY ISSUE 4 Staff & Contributors 6 Auction Calendar 8 Looking Back … 1934 10 News 62 Receptions 63 Events Calendar 64 Experts 65 Consignment Deadlines On the cover: McGregor Paxton’s Rose and Blue from the Paul H. Buchanan Jr. Collection (page 30) Movie poster for the Mickey Mouse short The Mad Doctor, considered one of the rarest of all Disney posters, from the Stephen Geppi collection (page 42) HERITAGE MAGAZINE — SPRING 2009 1 CONTENTS TREAsures 12 MOVIE POSTER: One sheet for 1933’s Flying Down to Rio, which introduced Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers to the world 14 COI N S: New Orleans issued 1854-O Double Eagle among rarest in Liberty series 16 FINE ART: Julian Onderdonk considered the father of Texas painting Batman #1 DC, 1940 CGC FN/VF 7.0, off-white to white pages Estimate: $50,000+ From the Chicorel Collection Vintage Comics & Comic Art Signature® Auction #7007 (page 35) Sandy Koufax Game-Worn Fielder’s Glove, 1966 Estimate: $60,000+ Sports Memorabilia Signature® Auction #714 (page 26) 2 HERITAGE MAGAZINE — SPRING 2009 CONTENTS AUCTION PrevieWS 18 ENTERTAINMENT: Ernie Kovacs and Edie Adams left their mark on the entertainment industry 23 CURRENCY: Legendary Deadwood sheriff Seth Bullock signed note as bank officer 24 MILITARIA: Franklin Pierce went from battlefields of war to the U.S. -

Among Producers Guild Nominees

LIFESTYLE37 WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 7, 2015 FILMS ‘Birdman,’ ‘Boyhood,’ ‘Imitation Game’ among Producers Guild nominees merican Sniper,” “Birdman,” “Boyhood,” The Danny Thomas Award for Outstanding “Foxcatcher,” “Gone Girl,” “Grand Birdman Producer of Episodic Television, Comedy: “A Budapest Hotel,” “The Imitation Producers: Alejandro G. Inarritu, John Lesher, Game,” “Nightcrawler,” “The Theory of James W. Skotchdopole The Big Bang Theory Everything” and “Whiplash” have been nominat- Producers: Faye Oshima Belyeu, Chuck Lorre, ed for the Producers Guild of America’s Darryl F. Boyhood Steve Molaro, Bill Prady Zanuck Award for top feature film. The winner Producers: Richard Linklater, p.g.a., Cathleen will be announced Jan. 24 in the PGA’s 26th Sutherland, p.g.a. Louie Producers: Pamela Adlon, Dave Becky, M. Foxcatcher Blair Breard, Louis C.K., Vernon Chatman, Adam Producers: Megan Ellison, p.g.a., Jon Kilik, Escott, Steven Wright p.g.a., Bennett Miller, p.g.a. Modern Family Gone Girl Producers: Paul Corrigan, Megan Ganz, Producer: Cean Chaffin, p.g.a. Abraham Higginbotham, Ben Karlin, Elaine Ko, Steven Levitan, Christopher Lloyd, Jeff Morton, The Grand Budapest Hotel Dan O’Shannon, Jeffrey Richman, Chris Smirnoff, Producers: Wes Anderson & Scott Rudin, Brad Walsh, Bill Wrubel, Sally Young, Danny Jeremy Dawson, Steven Rales Zuker The Imitation Game Orange Is the New Black Producers: Nora Grossman, p.g.a., Ido Producers: Mark A. Burley, Sara Hess, Jenji Ostrowsky, p.g.a., Teddy Schwarzman, p.g.a. Kohan, Gary Lennon, Neri Tannenbaum, Michael -

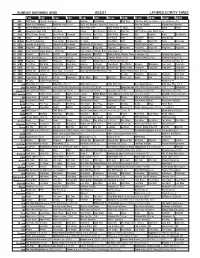

Sunday Morning Grid 8/22/21 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/22/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News Graham Bull Riding PGA Tour PGA Tour Golf The Northern Trust, Final Round. (N) 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å 2021 AIG Women’s Open Final Round. (N) Race and Sports Mecum Auto Auctions 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch David Smile 7 ABC Eyewitness News 7AM This Week Ocean Sea Rescue Hearts of Free Ent. 2021 Little League World Series 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Paid Prog. Mike Webb Harvest AAA Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Mercy Jack Hibbs Fox News Sunday The Issue News Sex Abuse PiYo Accident? Home Drag Racing 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Jack Hibbs AAA NeuroQ Grow Hair News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Fashion for Real Life MacKenzie-Childs Home MacKenzie-Childs Home Quantum Vacuum Å COVID Delta Safety: Isomers Skincare Å 2 2 KWHY Programa Resultados Revitaliza Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Great Scenic Railway Journeys: 150 Years Suze Orman’s Ultimate Retirement Guide (TVG) Great Performances (TVG) Å 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ Build a Better Memory Through Science (TVG) Country Pop Legends 3 0 ION NCIS: New Orleans Å NCIS: New Orleans Å Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 3 4 KMEX Programa MagBlue Programa Programa Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN R. -

Rick Ludwin Collection Finding

Rick Ludwin Collection Page 1 Rick Ludwin Collection OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Creator: Rick Ludwin, Executive Vice President for Late-night and Primetime Series, NBC Entertainment and Miami University alumnus Media: Magnetic media, magazines, news articles, program scripts, camera-ready advertising artwork, promotional materials, photographs, books, newsletters, correspondence and realia Date Range: 1937-2017 Quantity: 12.0 linear feet Location: Manuscript shelving COLLECTION SUMMARY The majority of the Rick Ludwin Collection focuses primarily on NBC TV primetime and late- night programming beginning in the 1980s through the 1990s, with several items from more recent years, as well as a subseries devoted to The Mike Douglas Show, from the late 1970s. Items in the collection include: • magnetic and vinyl media, containing NBC broadcast programs and “FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION” awards compilations, etc. • program scripts, treatments, and rehearsal schedules • industry publications • national news clippings • awards program catalogs • network communications, and • camera-ready advertising copy • television production photographs Included in the collection are historical narratives of broadcast radio and television and the history of NBC, including various mergers and acquisitions over the years. 10/22/2019 Rick Ludwin Collection Page 2 Other special interests highlighted by this collection include: • Bob Hope • Johnny Carson • Jay Leno • Conan O’Brien • Jimmy Fallon • Disney • Motown • The Emmy Awards • Seinfeld • Saturday Night Live (SNL) • Carson Daly • The Mike Douglas Show • Kennedy & Co. • AM America • Miami University Studio 14 Nineteen original Seinfeld scripts are included; most of which were working copies, reflecting the use of multi-colored pages to call out draft revisions. Notably, the original pilot scripts are included, which indicate that the original title ideas for the show were Stand Up, and later The Seinfeld Chronicles. -

American Comedy Institute Student, Faculty, and Alumni News

American Comedy Institute Student, Faculty, and Alumni News Michelle Buteau played Private Robinson in Fox’s Enlisted. She has performed on Comedy Central’s Premium Blend, Totally Biased with W.Kamau Bell, The Late Late Show with Craig Ferguson, Lopez Tonight and Last Comic Standing. She has appeared in Key and Peele and @Midnight. Michelle is a series regular on VH1’s Best Week Ever, MTV’s Walk of Shame, Oxygen Network’s Kiss and Tell, and was Jenny McCarthy’s sidekick on her late-night talk show Jenny. Craig Todaro (One Year Program alum) Craig performed in American Comedy Institute’s 25th Anniversary Show where he was selected by Gotham Comedy Club owner Chris Mazzilli to appear on Gotham Comedy Live. Craig is now a pro regular at Gotham Comedy Club where he recently appeared in Gotham Comedy All Stars. Yannis Pappas (One Year Program alum) Yannis recently appeared in his first Comedy Central Half Hour special. He has been featured on Gotham Comedy Live, VH1's Best Week Ever and CBS. He is currently the co-anchor of Fusion Live, a one-hour news magazine program on Fusion Network, which focuses on current events, pop culture and satire. He tours the world doing stand up comedy and is known for his immensely popular characters Mr. Panos and Maurica. Along with Director Jesse Scaturro, he is the co-founder of the comedy production company Ditch Films. Jessica Kirson is a touring national headliner. She recently made her film debut in Nick Cannon’s Cliques with Jim Breuer and George Lopez. -

35 Years of Nominees and Winners 36

3635 Years of Nominees and Winners 2021 Nominees (Winners in bold) BEST FEATURE JOHN CASSAVETES AWARD BEST MALE LEAD (Award given to the producer) (Award given to the best feature made for under *RIZ AHMED - Sound of Metal $500,000; award given to the writer, director, *NOMADLAND and producer) CHADWICK BOSEMAN - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom PRODUCERS: Mollye Asher, Dan Janvey, ADARSH GOURAV - The White Tiger Frances McDormand, Peter Spears, Chloé Zhao *RESIDUE WRITER/DIRECTOR: Merawi Gerima ROB MORGAN - Bull FIRST COW PRODUCERS: Neil Kopp, Vincent Savino, THE KILLING OF TWO LOVERS STEVEN YEUN - Minari Anish Savjani WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Robert Machoian PRODUCERS: Scott Christopherson, BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE MA RAINEY’S BLACK BOTTOM Clayne Crawford PRODUCERS: Todd Black, Denzel Washington, *YUH-JUNG YOUN - Minari Dany Wolf LA LEYENDA NEGRA ALEXIS CHIKAEZE - Miss Juneteenth WRITER/DIRECTOR: Patricia Vidal Delgado MINARI YERI HAN - Minari PRODUCERS: Alicia Herder, Marcel Perez PRODUCERS: Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, VALERIE MAHAFFEY - French Exit Christina Oh LINGUA FRANCA WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Isabel Sandoval TALIA RYDER - Never Rarely Sometimes Always NEVER RARELY SOMETIMES ALWAYS PRODUCERS: Darlene Catly Malimas, Jhett Tolentino, PRODUCERS: Sara Murphy, Adele Romanski Carlo Velayo BEST SUPPORTING MALE BEST FIRST FEATURE SAINT FRANCES *PAUL RACI - Sound of Metal (Award given to the director and producer) DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Alex Thompson COLMAN DOMINGO - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom WRITER: Kelly O’Sullivan *SOUND OF METAL ORION LEE - First -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website.