A Lucky Child

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Buergenthal Served As the United States Judge on the International Court of Justice (ICJ) from 2000 to 2010

Thomas Buergenthal served as the United States judge on the International Court of Justice (ICJ) from 2000 to 2010. Between 1979 and 1991, he was a judge and president of the Costa Rica-based Inter-American Court of Human Rights. He was as judge and president of the Administrative Tribunal of the Inter-American Development Bank (1989-94); vice chairman of the Claims Resolution Tribunal for Dormant Accounts in Switzerland. He also was a member of the UN Human Rights Committee; the UN Truth Commission for El Salvador; and the Ethics Commission of the International Olympic Committee. From 1989 – 2000 and again from 2010 – 2016 Buergenthal was the Lobingier Professor of Comparative Law & Jurisprudence, George Washington University Law School. He served as Dean of the Washington College of Law of the American University from 1980-1985. His other academic posts included: Professor of Law, State University of N.Y. (Buffalo) Law School; Fulbright & Jaworski Professor, University of Texas Law School; I.T. Cohen Professor, Emory University Law School. While at Emory, he also served as the Director of the Human Rights Program of the Carter Center. Buergenthal earned the following academic degrees: B.A. (1957), Bethany College, West Virginia; J.D. (1960), New York University Law School (Root- Tilden Scholar); LL.M. (1961) and S.J.D (1968), Harvard Law School. He is the recipient of the following honorary degrees: Bethany College, 1981; University of Heidelberg, 1986; Free University of Brussels (V.U.B), 1994; State University of New York (Buffalo), 2000; American University (Washington, D.C.), 2002; University of Minnesota, 2003; George Washington University, 2004; University of Göttingen, 2007; New York University, 2008; St. -

THE POLISH POLICE Collaboration in the Holocaust

THE POLISH POLICE Collaboration in the Holocaust Jan Grabowski The Polish Police Collaboration in the Holocaust Jan Grabowski INA LEVINE ANNUAL LECTURE NOVEMBER 17, 2016 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. First printing, April 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Jan Grabowski THE INA LEVINE ANNUAL LECTURE, endowed by the William S. and Ina Levine Foundation of Phoenix, Arizona, enables the Center to bring a distinguished scholar to the Museum each year to conduct innovative research on the Holocaust and to disseminate this work to the American public. Wrong Memory Codes? The Polish “Blue” Police and Collaboration in the Holocaust In 2016, seventy-one years after the end of World War II, the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs disseminated a long list of “wrong memory codes” (błędne kody pamięci), or expressions that “falsify the role of Poland during World War II” and that are to be reported to the nearest Polish diplomat for further action. Sadly—and not by chance—the list elaborated by the enterprising humanists at the Polish Foreign Ministry includes for the most part expressions linked to the Holocaust. On the long list of these “wrong memory codes,” which they aspire to expunge from historical narrative, one finds, among others: “Polish genocide,” “Polish war crimes,” “Polish mass murders,” “Polish internment camps,” “Polish work camps,” and—most important for the purposes of this text—“Polish participation in the Holocaust.” The issue of “wrong memory codes” will from time to time reappear in this study. -

Council and Participants

The American Law Institute OFFICERS * Roswell B. Perkins, President Edward T. Gignoux, 1st Vice President Charles Alan Wright, 2nd Vice President Bennett Boskey, Treasurer Geoffrey C. Hazard, Jr., Director Paul A. Wolkin, Executive Vice President COUNCIL * Shirley S. Abrahamson Madison Wisconsin Philip S. Anderson Little Rock Arkansas Richard Sheppard Arnold Little Rock Arkansas Frederick A. Ballard Alexandria Virginia Bennett Boskey Washington District of Columbia Michael Boudin Washington District of Columbia Hugh Calkins Cleveland Ohio Gerhard Casper Chicago Illinois William T. Coleman, Jr. Washington District of Columbia Roger C. Cramton Ithaca New York Lloyd N. Cutler Washington District of Columbia R. Ammi Cutter** Cambridge Massachusetts William H. Erickson Denver Colorado Thomas E. Fairchild Madison Wisconsin Jefferson B. Fordham Salt Lake City Utah John P. Frank Phoenix Arizona George Clemon Freeman, Jr. Richmond Virginia Edward T. Gignoux Portland Maine Ruth Bader Ginsburg Washington District of Columbia Erwin N. Griswold Washington District of Columbia Conrad K. Harper New York New York Clement F. Haynsworth, Jr. Greenville South Carolina Vester T. Hughes, Jr. Dallas Texas Joseph F. Johnston Birmingham Alabama Nicholas deB. Katzenbach Morristown New Jersey Herma Hill Kay Berkeley California Pierre N. Leval New York New York Edward Hirsch Levi Chicago Illinois Betsy Levin Washington District of Columbia Hans A. Linde Salem Oregon Martin Lipton New York New York *As of December 1, 1987 ** Chairman Emeritus OFFICERS AND COUNCIL Robert MacCrate New York New York Hale McCown Lincoln Nebraska Carl McGowan Washington District of Columbia Vincent L. McKusick Portland Maine Robert H. Mundheim Philadelphia Pennsylvania Roswell B. Perkins New York New York Ellen Ash Peters Hartford Connecticut Louis H. -

International Court of Justice

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE Peace Palace, Carnegieplein 2, 2517 KJ The Hague, Netherlands Tel.: +31 (0)70 302 2323 Fax: +31 (0)70 364 9928 Website: www.icj-cij.org Press Release Unofficial No. 2010/17 10 June 2010 Judge Thomas Buergenthal will resign as Member of the International Court of Justice with effect from 6 September 2010 THE HAGUE, 10 June 2010. Judge Thomas Buergenthal will resign as Member of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) with effect from 6 September 2010. His term would have expired on 5 February 2015. The United Nations has fixed 9 September 2010 as the date for the election of his successor by the Security Council and the General Assembly. The Member of the Court then elected will complete Judge Buergenthal’s term. Judge Buergenthal has been a Member of the Court since 2 March 2000. After his first term, he was re-elected as from 6 February 2006. Former Judge and President of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and the Administrative Tribunal of the Inter-American Development Bank, Judge Buergenthal is also a Member of the American Bar Association, the American Society of International Law, the American Law Institute, the Council on Foreign Relations and the German Society of International Law. In addition, he is an associé of the Institut de droit international. Holder of numerous prizes and distinctions, Judge Buergenthal sits on the Editorial Board of various publications. He is the author of many books, essays and articles. ___________ Judge Buergenthal’s official biographical note is available on the Court’s website (www.icj-cij.org) under the heading “Members of the Court/Current Members”. -

Thomas Buergenthal — a Lucky Child by Katie Davis

Thomas Buergenthal — A Lucky Child by Katie Davis Katie Davis: I’m Katie Davis. We know the history of World War II — and still, when someone tells his or her own story, we always learn. Thomas Buergenthal saw the Nazi concentration camps Auschwitz and Sachsenhausen through a child’s eyes. He was separated from his parents in the camps and managed to survive by his wits ... and luck. And that is what he called his first book: A Lucky Child. And Thomas Buergenthal turned his luck into a force for change. Begin with a bicycle and a pony. [AUDIO: OLD MUSIC ON VICTROLA HIT UNDER; MAX BLOCH TENOR SINGS GERMAN WAR SONG] Katie Davis: The boy learns to ride them both — in the dust of the camp, out of sight of the S.S. guard. Later, the Polish army gives him the circus pony and a uniform. It is 1945, and he rides to Berlin with the Polish Army to fight the last German soldiers. [MUSIC (FADES AWAY)] Katie Davis: He was Tommy then. Six years old at first, then 10 and 11, born to German Jewish/Polish parents. And the family was forced into a ghetto, in Kielce, Poland. [NEWSREEL GERMAN/WARSAW GHETTO ** JEWS MUST BE IN JEWISH AREAS.] Katie Davis: The family was forced into a ghetto in Kielce, Poland, and he can remember his father, shaving at the kitchen sink while orders were shouted from the street. Thomas Buergenthal: I observed my father, whose great strength was that you could see that he always thought things out before he did it. -

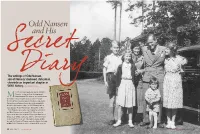

About Odd Nansen

Odd Nansen and His The writings of Odd Nansen, June 1945: Odd nansen is reunited with his family son of Norway’s beloved statesman, after WWII. chronicle an important chapter in WWII history. By Timothy J. Boyce ost Norwegian-Americans know of Fridtjof Nansen—polar explorer, statesman and M humanitarian. His memory and achievements are widely celebrated in Norway, as attested by the October 2011 sesquicentennial celebration of his birth. But far fewer in America know about the remarkable y L life and achievements of his son, Odd Nansen, and in i M FA s particular his World War II diary, “From Day to Day.” ’ Odd Nansen, the fourth of five children of Fridtjof NANSEN and Eva Nansen, was born in 1901. He received a f ODD f O degree in architecture from the Norwegian Institute of esy rt u Technology (NTH), and from 1927 to 1930 lived and O PH c PH a worked in New York City. His father’s failing health R g brought Odd back to Norway, and after Fridtjof’s death PHOTO in May 1930 Nansen decided to remain. Following in 16 Viking May 2013 sonsofnorway.com sonsofnorway.com Viking May 2013 17 Nansen never intended to publish the diary, Fridtjof’s humanitarian secret diary, recording his From Day to Day Norwegians arrested during His entries also reveal but wrote it simply as a way to communicate with footsteps, Odd Nansen experiences, hopes, dreams The diary, later published the war, almost 7,500 were the quiet strength, and his wife Kari, and as a means of sorting out his helped establish and fears. -

Dr. Bodnar, Excellences, Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen

Zdzisław Kędzia Laudatio for Professor Thomas Buergenthal Professor Buergenthal, Madame Buergenthal, Mr. Ombudsman - Dr. Bodnar, Excellences, Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen It is a great pleasure and a genuine honour for me to present this laudatio which should not only attempt to recall some highlights from the striking life of the todays awardee – Professor and Judge Thomas Buergenthal - but also pay tribute to his outstanding achievements as global human rights advocate. Yet, taking into account the richness of his experience, an attempt to summarize it looks like a mission impossible. Luckily, Professor Buergenthal has a truly friendly attitude to others and decided to help those who are facing tasks similar to mine today. I am thinking here about his book “A Lucky Child. A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz as a Young Boy”. Initially published in 2007, it has subsequently been translated into many languages, including Polish. To say that this book is highly interesting and very important would be still an understatement. Since, this is an exceptional publication - it puts forward, in a touchy epic way, fundamental questions about humanity and attempts to provide universal responses. Elie Wiesel, himself a Holocaust survivor and an author of his own memoir “Night”, Nobel Peace Prize laureate, and also a friend of Thomas Buergenthal wrote in the preface to “A Lucky Child”: “How can those who have never been put to the test understand how human nature may bend under duress? Why does one man become a pitiless Kapo and victimize an old friend or even his own relative? What makes one man choose to exercise power through cruelty, while another – from exactly the same background – refuses to do so in the name of enfeebled and downtrodden humanity? Thomas watches, learns and remembers. -

A LUCKY CHILD a Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz As a Young

A LUCKY CHILD A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz as a Young Boy Thomas Buergenthal Dedicated to the memory of my parents, Mundek and Gerda Buergenthal, whose love, strength of character and integrity inspired this book CONTENTS Table of Contents Preface vii Chapter 1: From Lubochna to Poland ...................................................................1 Chapter 2: Katowice ............................................................................................13 Chapter 3: The Ghetto of Kielce .........................................................................23 Chapter 4: Auschwitz ..........................................................................................43 Chapter 5: The Auschwitz Death Transport.......................................................62 Chapter 6: Liberation..........................................................................................71 Chapter 7: Into the Polish Army.........................................................................85 Chapter 8: Waiting to Be Found.........................................................................98 Chapter 9: A New Beginning ...........................................................................114 Chapter 10: Life in Germany.............................................................................123 Chapter 11: To America ....................................................................................144 Epilogue: 153 Acknowledgements: ...........................................................................................167 -

Thomas Buergenthal Interview

Interview Prof. Dr. Claus Kreß, Daniel Stahl Quellen zur Geschichte der Menschenrechte Thomas Buergenthal Thomas Buergenthal was born in 1934 as the child of German-Polish Jews in Czechoslovakia. He and his parents were forced into the Jewish ghetto of Kielce, Poland at the start of the Second World War, and in mid-1944 were deported from there to Auschwitz. After the war Buergenthal lived for a few years with his mother, in the north-central German town of Göttingen before moving to the United States at the age of seventeen. There he studied law and took up a university career. He belonged to a small group of international law specialists in the U.S. who in the 1970s undertook to lend new meaning to the issue of human rights. He advised the founding of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and was appointed to it as a judge by Costa Rica in 1979. He served as a member of the Truth Commission for El Salvador appointed by the United Nations in 1992, and as a judge of the International Court of Justice at The Hague from 2000 to 2010. Interview Prof. Dr. Claus Kreß, Director of the Institute for International Peace and Security Law of the University of Cologne, first met Prof. Dr. Buergenthal in April 2014 and asked him at the time if he would submit to a biographical interview. The interview took place on March 4, 2015 in Prof. Buergenthal’s office at George Washington University. Prof. Kreß and Dr. Daniel Stahl, coordinator of the Study Group »Human Rights in the 20th Century«, interviewed the legal scholar for eight hours, with a break of one hour. -

GW Law's International and Comparative Law Program

www.law.gwu.edu/international INTERNATIONAL AND COMPARATIVE LAW GW Law’s International and Comparative FACULTY HIGHLIGHTS Law Program prepares the next Paul Schiff Berman: Editor, Research Handbook on Global Legal generation of global legal professionals Pluralism (Oxford University Press) Francesca Bignami: Member, Executive Committee of the by offering one of the most extensive American Society of Comparative Law and of the Electronic Privacy Information Center Advisory Board international law curricula in the country. Karen B. Brown: Member, American Law Institute Hon. Thomas Buergenthal (Emeritus): former Judge, Our international and comparative law faculty is recognized International Court of Justice in The Hague for the breadth and depth of its experience. In addition, the Rosa M. Celerio: Program Director; Worked on international program benefits from GW Law faculty members in other human rights law, discrimination, and gender issues for the UN areas—including intellectual property law, government Development Fund for Women (currently, UN Women) procurement, and national security law—who routinely examine Steve Charnovitz: Member, Editorial Board, World Trade Review and influence international and foreign law in their teaching Donald C. Clarke: Member, Council on Foreign Relations and scholarship. and expert on Chinese law A vital part of the GW Law experience stems from our Robert J. Cottrol: Specialist in American legal history unparalleled location in the heart of Washington, D.C., across Laura Dickinson: Counselor, U.S. Department of Defense the street from the International Monetary Fund and the David Fontana: Specialist in constitutional issues, writes for World Bank, two blocks from internationally known law firms both scholarly and general interest publications, including, most frequently, Slate and The New Republic on K Street, three blocks from the U.S. -

A Lucky Child a Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz As a Young Boy 1St Edition Download Free

A LUCKY CHILD A MEMOIR OF SURVIVING AUSCHWITZ AS A YOUNG BOY 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Thomas Buergenthal | 9780316339186 | | | | | A Lucky Child: A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz as a Young Boy Summary Add a Summary. Hardcoverpages. Get A Copy. Last edited by Clean Up Bot. That he managed to survive all do these experiences he puts down to "luck" knowing that sounds odd, and to the length of time he spent drifting into hell which prepared him to survive. Finally, though, through a lucky circuitous route, his mother, who has survived and never given up hope of finding him, succeeds in locating him. His accent and diction are beautiful and I almost hated to have the book turned over to the professional reader, but he was equally good. Separated at Auschwitz from his mother, he was able to stay with his father for quite some time. He admits that memory can be changed some Not in Library. I thought, perhaps his youth prevented him from truly knowing the full measure of loss that older people experienced, both in their dignity and loss of loved ones. Mengele and Auschwitz. No matter how many books you may have read about the Holocaust, read this one too. Saved Searches Advanced Search. His writing here is flowing and stark, and he doesn't get bogged down with unnecessary repetition like last few autobiographies I've read. The author takes a rather unsentimental tone throughout that puts in sharper relief the evils of Hitler's Germany as well as the essential humanity, both for good and for evil, of many of A Lucky Child A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz As a Young Boy 1st edition people trapped within it. -

The Organization of American States by Natalie Knowlton

H UMAN R IGHTS & H UMAN W ELFARE The Organization of American States by Natalie Knowlton The international community focused its attention on protecting human rights in response to horrendous human rights abuses during World War II. Latin and South American states enacted The American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man [Declaration] in 1948, shortly after their creation of the Organization of American States [OAS]. While the Declaration set forth dozens of rights, little was done in the next decade to establish a means for their protection. The 1948 Charter of the OAS [Charter] originally provided for a Commission on Human Rights but one was not formally established until the amending 1959 Protocol of Buenos Aires [Protocol]. The Protocol established the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, but gave it little power and only a vague mandate to promote human rights. Recognizing ongoing abuses and the need to strengthen the human rights system, the OAS adopted the American Convention on Human Rights [Convention] in 1978. The Convention reaffirmed the region's commitment to human rights and empowered the Commission. It also established the Inter-American Court of Human Rights [Court] to work with the Commission and further ensure compliance with the Convention. Combined, the Commission and the Court form the sole organ dealing with the promotion and protection of human rights in the Americas. The Commission publishes reports, carries out site visits and reviews petitions which it may then pass along to the Court. The Court has contentious and advisory jurisdiction over signatory members and its decisions are binding.