Tlapanec-Mangue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tlacoapa, Guerrero

Informe Anual Sobre La Situación de Pobreza y Rezago Social Tlacoapa, Guerrero I. Indicadores sociodemográficos II. Medición multidimensional de la pobreza Tlacoapa Guerrero Indicador Indicadores de pobreza y vulnerabilidad (porcentajes), (Municipio) (Estado) 2010 Población total, 2010 9,9673,388,768 Total de hogares y viviendas 2,064805,230 Vulnerable por particulares habitadas, 2010 carencias social Tamaño promedio de los hogares 4.84.2 (personas), 2010 0 23.1 Vulnerable por Hogares con jefatura femenina, 2010 653 216,879 0.1 ingreso Grado promedio de escolaridad de la 18.3 81.6 No pobre y no 5.77.3 población de 15 o más años, 2010 58.5 vulnerable Total de escuelas en educación básica y 55 10,975 Pobreza moderada media superior, 2010 Personal médico (personas), 2010 18 4,825 Pobreza extrema Unidades médicas, 2010 81,169 Número promedio de carencias para la 4.53.4 población en situación de pobreza, 2010 Número promedio de carencias para la Indicadores de carencia social (porcentajes), 2010 población en situación de pobreza 4.64.1 994.34 3 92.192 1 95 extrema, 2010 78.5 Fuentes: Elaboración propia con información del INEGI y CONEVAL. 60.7 58.9 56.6 57.7 38.9 40.7 42.7 28.4 27.3 29.2 22.9 24.8 • La población total del municipio en 2010 fue de 9,967 20.7 15.2 personas, lo cual representó el 0.3% de la población en el estado. Carencia por Carencia por Carencia por Carencia por Carencia por Carencia por • En el mismo año había en el municipio 2,064 hogares (0.3% del rezago acceso a los acceso a la calidad y servicios acceso a la total de hogares en la entidad), de los cuales 653 estaban educativo servicios de seguridad espacios de básicos en la alimentación encabezados por jefas de familia (0.3% del total de la entidad). -

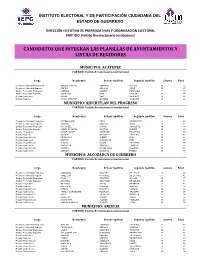

Candidatos Que Integran Las Planillas De Ayuntamientos Y Listas De Regidores

INSTITUTO ELECTORAL Y DE PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO DIRECCIÓN EJECUTIVA DE PRERROGATIVAS Y ORGANIZACIÓN ELECTORAL PARTIDO: Partido Verde Ecologista de México CANDIDATOS QUE INTEGRAN LAS PLANILLAS DE AYUNTAMIENTOS Y LISTAS DE REGIDORES MUNICIPIO: ACATEPEC PARTIDO: Partido Verde Ecologista de Mexico Cargo Nombre(s) Primer Apellido Segundo Apellido Género Edad Presidente Municipal Propietario VIDAL NERI BASURTO H 38 Presidente Municipal Suplente MAURO HILARIO EULOGIA H 39 Sindico Procurador Propietario EPIFANIA GARCIA FLORES M 47 Sindico Procurador Suplente ROSENDA ALFONZO AURELIO M 27 Regidor Propietario ESTEBAN MARCELINO VAZQUEZ H 43 Regidor Suplente TIMOTEO ESPINOZA JULIO H 29 Regidor Propietario (2) NORMA MAURILO MORALES M 27 Regidor Suplente (2) EDUWIGIS HILARION BERNARDINO M 28 Regidor Propietario (3) MARTIN LORENZO MODESTA H 50 Regidor Suplente (3) FELIPE MENDEZ FERRER H 36 Regidor Propietario (4) ELVIRA BASILIO LIBRADO M 25 Regidor Suplente (4) GLAFIRA AURELIO CRUZ M 26 MUNICIPIO: AJUCHITLAN DEL PROGRESO PARTIDO: Partido Verde Ecologista de Mexico Cargo Nombre(s) Primer Apellido Segundo Apellido Género Edad Presidente Municipal Propietario EDGAR RAMIRO DIEGO SANTIAGO H 22 Presidente Municipal Suplente FULGENCIO VERGARA URBANO H 29 Sindico Procurador Propietario LADY PIZARRO MONDRAGON M 29 Sindico Procurador Suplente MERLI CRUZ LOPEZ M 22 Regidor Propietario ERIC PANTALEON ALVAREZ H 35 Regidor Suplente JOSE OLEGARIO CALDERON CERVANTES H 37 Regidor Propietario (2) SOLYANET LARA ANTUNEZ M 26 Regidor Suplente (2) -

Proyección De Casillas Corte 30 De Septiembre De 2016

INSTITUTO ELECTORAL Y DE PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO DIRECCIÓN EJECUTIVA DE ORGANIZACIÓN Y CAPACITACIÓN ELECTORAL COORDINACIÓN DE ORGANIZACIÓN ELECTORAL Proyección con Lista Nominal de casillas básicas, contiguas, extraordinarias, y especiales por distrito y municipio con corte al 30 de septiembre de 2016. Total de Total por Casillas por Secciones sin Distrito Municipio Básicas Contiguas Extraordinarias Especiales secciones municipio distrito rango CHILPANCINGO DE LOS BRAVO 47 47 90 0 4 141 0 1 141 TOTAL: 47 47 90 0 4 141 0 CHILPANCINGO DE LOS BRAVO 57 57 96 3 1 157 0 2 157 TOTAL: 57 57 96 3 1 157 0 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 70 69 96 0 8 173 1 3 173 TOTAL: 70 69 96 0 8 173 1 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 79 79 83 0 4 166 0 4 166 TOTAL: 79 79 83 0 4 166 0 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 58 58 89 2 0 149 0 5 149 TOTAL: 58 58 89 2 0 149 0 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 53 53 82 0 1 136 0 6 136 TOTAL: 53 53 82 0 1 136 0 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 39 39 106 17 1 163 0 7 163 TOTAL: 39 39 106 17 1 163 0 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 21 21 30 0 1 52 0 8 COYUCA DE BENÍTEZ 60 59 36 3 1 99 151 1 TOTAL: 81 80 66 3 2 151 1 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ 62 62 75 4 1 142 0 9 142 TOTAL: 62 62 75 4 1 142 0 TÉCPAN DE GALEANA 38 37 23 0 1 61 1 ATOYAC DE ÁLVAREZ 73 67 25 4 0 96 6 10 182 BENITO JUÁREZ 15 15 10 0 0 25 0 TOTAL: 126 119 58 4 1 182 7 ZIHUATANEJO DE AZUETA 26 26 40 1 1 68 0 PETATLÁN 56 53 21 0 0 74 3 11 181 TÉCPAN DE GALEANA 29 29 7 3 0 39 0 TOTAL: 111 108 68 4 1 181 3 ZIHUATANEJO DE AZUETA 39 38 50 4 3 95 1 COAHUAYUTLA 31 29 0 3 0 32 2 12 179 LA UNIÓN 33 33 11 8 0 52 0 TOTAL: 103 100 61 15 3 179 3 COORDINACIÓN DE ORGANIZACIÓN ELECTORAL 03:36 p. -

GUERRERO SUPERFICIE 63 794 Km² POBLACIÓN 3 115 202 Hab

A MORELIA A PÁTZCUARO A ZITÁCUARO 99 km. A ZITÁCUARO 99 km A NAUCALPAN 67 km A ENT. CARR. 134 A C Villa Madero E F G I J K F.C. A K B D H 102°00' 282 km 30' A MORELIA 101°00' 30' 100°00' 30' 99°00' 30' APIZACO 50 km A APIZACO A CD. DE 10 km MÉXICO CIUDAD DE T MEX 35 km Y 15 F.C. A MÉXICO BUENAVISTA TLAXCALA 4 AL CENTRO 19 km 4 M L N MEX 32 15 1 C MEX 37 TOLUCA D GUERRERO SUPERFICIE 63 794 km² POBLACIÓN 3 115 202 hab. I S Á T A MEX R Ario de Rosales 51 I 76 F T E O 40 GUERRERO D Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transportes C 22 E Gabriel Zamora R 31 X. A ORIZABA 150 km 69 A L Dirección General de Planeación km 114 TEHUACÁN A X = 190 000 m Y = 2 118 000 m F.C. A TEHUACÁN A F.C. Esata carta fue coordinada y supervisada por la Subdirección de Cartografía de la A 33 GUERRERO (2008) Dirección de Estadística y Cartografía. MEX 3 Tenango de Arista 120 34 Para mayor información de la Infraestructura del Sector en el Estado diríjase al O Centro SCT ubicado en: Av. Dr. y Gral. Gabriel Leyva Alarcon s/n esq. 159 Nocupétaro O Av. Juventud; Col. Burócratas, C.P. 39090, Chilpancingo, Gro. 5 NUEVA ITALIA Temascaltepec DE RUIZ rancho 24 Punga MEX Río MEX 95 18 32 C 55 112 19 PUEBLA H 152 9 31 19°00' MEX 32 I 11 115 2 D 56 MEX 134 TENANCINGO DE DEGOLLADO 39 MEX X 34 115 M É 127 16 C 83 CUERNAVACA Presa Manuel Ávila Camacho Tiquicheo Río 5 33 5 ATLIXCO San San Miguel Jerónimo 50 33 42 Río MEX Mesa del Zacate TEMIXCO 1 190 Chiquito Eréndira El Cirián A MEX I 37 Pungarancho La Paislera Ixtapan de la Sal 3 MEX 60 Naranjo 95 La Playa Pácuaro El D CUAUTLA Los Tepehuajes Río M La Joya El Tule 18 Pinzán Gacho X = 568 000 m Y = 2 076 000 m El Ojo de Agua El Agua Buena Los Jazmines Los Guajes Arroyo Salado L. -

Ayuntamientos Pri.Pdf

INSTITUTO ELECTORAL Y DE PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO DIRECCIÓN EJECUTIVA DE PRERROGATIVAS Y ORGANIZACIÓN ELECTORAL PARTIDO: Partido Revolucionario Institucional CANDIDATOS QUE INTEGRAN LAS PLANILLAS DE AYUNTAMIENTOS Y LISTAS DE REGIDORES MUNICIPIO: ACATEPEC PARTIDO: Partido Revolucionario Institucional Cargo Nombre(s) Primer Apellido Segundo Apellido Género Edad Presidente Municipal Propietario SELENE CRISTAL SORIANO GARCIA M 35 Presidente Municipal Suplente RUFINA IGNACIO CRUZ M 27 Sindico Procurador Propietario LIBRADO GARCIA PASCUALA H 42 Sindico Procurador Suplente MAURICIO NERI GARCIA H 24 Regidor Propietario ESTER NERI BASURTO M 22 Regidor Suplente MARIA JENNIFER ORTUÑO SANCHEZ M 26 MUNICIPIO: AJUCHITLAN DEL PROGRESO PARTIDO: Partido Revolucionario Institucional Cargo Nombre(s) Primer Apellido Segundo Apellido Género Edad Presidente Municipal Propietario VICTOR HUGO VEGA HERNANDEZ H 45 Presidente Municipal Suplente RAMIRO ARAUJO NAVA H 37 Sindico Procurador Propietario MA. ISABEL CHAMU ANACLETO M 38 Sindico Procurador Suplente ANGELICA MARIA OLMEDO GOMEZ M 42 Regidor Propietario MIGUEL ANGEL CAMBRON FIGUEROA H 49 Regidor Suplente WILVERT MARTINEZ CATALAN H 45 Regidor Propietario (2) FRANCISCA JAIMEZ RIOS M 27 Regidor Suplente (2) BERTHA GUILLERMO PIÑA M 37 Regidor Propietario (3) ELICEO ROJAS VALENTIN H 25 Regidor Suplente (3) PERFECTO SANCHEZ LIMONES H 32 Regidor Propietario (4) JUSTINA MAYORAZGO HIGUERA M 42 Regidor Suplente (4) EUFEMIA BLANCAS PINEDA M 37 MUNICIPIO: ALCOZAUCA DE GUERRERO PARTIDO: Partido Revolucionario -

ENTIDAD MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD LONG LAT Guerrero Acapulco De

ENTIDAD MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD LONG LAT Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez AGUA DEL PERRO 993354 170544 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez AGUAS CALIENTES 993826 165033 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez ALTO DEL CAMARÓN 993454 170305 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez AMATEPEC 993029 165849 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez AMATILLO 993958 164913 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez APALANI 993522 165113 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez APANHUAC (APANGUAQUE) 993520 165448 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez BARRA VIEJA 993736 164129 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez BARRIO NUEVO DE LOS MUERTOS 993238 165334 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez EL BEJUCO 994225 164927 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez CACAHUATEPEC 993643 165311 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez LA CALERA 994120 170252 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez CAMPANARIO 993417 165006 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez EL CANTÓN 993550 165338 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez EL CARRIZO 993712 165217 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez CERRO DE PIEDRA 993745 164634 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez COLONIA GUERRERO (LOS GUAJES) 993647 170225 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez LA CONCEPCIÓN 993911 165250 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez LAS CRUCES DE CACAHUATEPEC 993658 165050 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez DOS ARROYOS 993855 170116 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez EJIDO NUEVO 994408 165830 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez ESPINALILLO 993524 165356 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez LA ESTACIÓN 993958 164603 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez GARRAPATAS 993941 165514 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez HUAJINTEPEC 993112 165823 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez HUAMUCHITOS 993446 165339 Guerrero Acapulco de Juárez LOS ÁLAMOS 993718 165346 Guerrero -

8. LISTA CANDIDATURAS PES.Xlsx

INSTITUTO ELECTORAL Y DE PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO LISTA DE CANDIDATURAS DE AYUNTAMIENTOS PARTIDO ENCUENTRO SOLIDARIO NO. MUNICIPIO PARTIDO NOMBRE CARGO GÉNERO 1 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PES RAUL MAURICIO LEGARRETA MARTINEZ PRESIDENCIA MUNICIPAL PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 2 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PES ANTONIO PALAZUELOS ROSENZWEIG PRESIDENCIA MUNICIPAL SUPLENTE HOMBRE 3 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PES MA DEL ROSARIO AGUIRRE SANTIBAÑEZ SINDICATURA 1 PROPIETARIA MUJER 4 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PES NORMA IRIS RIOS AVILA SINDICATURA 1 SUPLENTE MUJER 5 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PES LUIS ENRIQUE VILLALVAZO RAMIREZ SINDICATURA 2 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 6 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PES VICTOR MANUEL MENDOZA JUAREZ SINDICATURA 2 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 7 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PES MARICELA DEL CARMEN RUIZ MASSIEU REGIDURIA 1 PROPIETARIA MUJER 8 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PES ANA LILIA SANTOS NAVA REGIDURIA 1 SUPLENTE MUJER 9 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PES REYNALDO CASTILLO DIAZ REGIDURIA 2 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 10 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PES JOSE LENIN HEREDIA AVILA REGIDURIA 2 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 11 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PES LUCIA MARTINEZ SALGADO REGIDURIA 3 PROPIETARIA MUJER 12 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PES KARLA FIERRO ZAPATA REGIDURIA 3 SUPLENTE MUJER 13 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PES MIGUEL ANGEL LOPEZ CASTREJON REGIDURIA 4 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 14 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PES LUIS ELEAZAR SOLIS PALACIOS REGIDURIA 4 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 15 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PES LUCILA GUILLEN QUEVEDO REGIDURIA 5 PROPIETARIA MUJER 16 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PES SINDY AMERICA ORBE FUENTES REGIDURIA 5 SUPLENTE MUJER 17 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PES ISRAEL WILLIAMS MANZANARES -

Acuerdo 030/So/24-02-2021

INSTITUTO ELECTORAL Y DE PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO ACUERDO 030/SO/24-02-2021 POR EL QUE SE DETERMINAN LOS TOPES DE GASTOS DE CAMPAÑAS, PARA LAS ELECCIONES DE GUBERNATURA, DIPUTACIONES LOCALES POR EL PRINCIPIO DE MAYORÍA RELATIVA Y AYUNTAMIENTOS, PARA EL PROCESO ELECTORAL ORDINARIO DE GUBERNATURA DEL ESTADO, DIPUTACIONES LOCALES Y AYUNTAMIENTOS 2020-2021. A N T E C E D E N T E S 1. El día 15 de abril de 2016, el Consejo General del Instituto Electoral y de Participación Ciudadana del Estado de Guerrero, emitió el Acuerdo 023/SE/15-04-2016, mediante el cual se aprueba el informe de la consulta realizada en el municipio de Ayutla de los Libres, Guerrero, en atención a la solicitud de elección por usos y costumbres que presentaron diversas autoridades de dicho municipio, y se valida el procedimiento y los resultados de la misma en cumplimiento a la sentencia dictada por el Tribunal Electoral del Estado de Guerrero, en el expediente TEE/SSI/RAP/033/2016 y acumulados. 2. El día 21 de diciembre de 2016, el Consejo General del Instituto Nacional Electoral emitió el Acuerdo INE/CG864/2016, por el que se aprueba la demarcación territorial de los distritos electorales uninominales locales en que se divide el Estado de Guerrero y sus respectivas cabeceras distritales. 3. El 14 de agosto de 2020, el Consejo General del Instituto Electoral y de Participación Ciudadana del Estado de Guerrero, mediante Acuerdo 031/SE/14-08-2020, aprobó el calendario del Proceso Electoral Ordinario de Gubernatura del Estado, Diputaciones Locales y Ayuntamientos 2020-2021, mismo que fue modificado mediante diverso Acuerdo 018/SO/27-01-2021. -

Diario 09 17-Dic-02

CHILPANCINGO, GUERRERO, MARTES 17 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2002 DIARIO DE LOS DEBATES DEL H. CONGRESO DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO PRESIDENTE Diputado Fredy García Guevara Año I Primer Periodo Ordinario LVII Legislatura Núm. 9 SESIÓN PÚBLICA CELEBRADA EL - Escrito signado por el licenciado 17 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2002 Luis Camacho Mancilla, oficial mayor de este Honorable SUMARIO Congreso, por el que hace del conocimiento la denuncia de ASISTENCIA pág. 2 revocación del cargo presentada por ciudadanos de diversas ORDEN DEL DÍA pág. 3 comunidades del municipio de Tlacoapa, Guerrero, en contra ACTA DE LA SESIÓN de los ciudadanos Germán ANTERIOR pág. 4 Galeana Sixto y José Alejandro Silva, regidor y secretario CORRESPONDENCIA auxiliar, respectivamente, del Honorable Ayuntamiento del - Escrito signado por el ciudadano municipio de Tlacoapa, Guerrero pág. 7 doctor Alejo Ramírez Pacheco, expresidente del Honorable - Escrito signado por los Ayuntamiento del municipio de integrantes del municipio de Zirándaro de los Chávez, Huamuxtitlán, Guerrero, por el Guerrero, por el que envían que envía un ejemplar del Tercer iniciativa de Ley de Ingresos para Informe de Gobierno Municipal pág. 5 el ejercicio fiscal del año 2003 pág. 7 Escrito signado por el ciudadano - - Escrito signado por el ciudadano profesor Jorge Díaz Martínez, René González Justo, presidente exsecretario del Honorable del Honorable Ayuntamiento del Ayuntamiento del municipio de municipio de Marquelia, Taxco de Alarcón, Guerrero, por Guerrero, por el que envía el que envía un ejemplar del iniciativa de Ley de Ingresos para Tercer Informe de Gobierno el ejercicio fiscal del año 2003 pág. 8 Municipal pág. 6 - Escrito signado por el ciudadano - Escrito signado por el ciudadano Alberto López Rosas, presidente doctor Saúl Alarcón Abarca, del Honorable Ayuntamiento del presidente del Honorable municipio de Acapulco de Juárez, Ayuntamiento del municipio de Guerrero, por el que envía Chilpancingo de los Bravo, iniciativa de Ley de Ingresos para Guerrero, por el que notifica la el ejercicio fiscal del año 2003 pág. -

Si No La Haces, ¿De Qué Vives? Le Vamos a Enseñar Poco Tlapaneco

Cuadernos Interculturales ISSN: 0718-0586 [email protected] Universidad de Playa Ancha Chile Barragán Trejo, Daniel "Si no la haces, ¿de qué vives? Le vamos a enseñar poco tlapaneco": Un desplazamiento lingüístico en proceso entre migrantes mi'phaa (tlapanecos de Tlacoapa) en Tlaquepaque, Jalisco, México Cuadernos Interculturales, vol. 7, núm. 12, 2009, pp. 21-46 Universidad de Playa Ancha Viña del Mar, Chile Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=55211259003 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Cuadernos Interculturales. Año 7, Nº 12. Primer Semestre 2009, pp. 21-46 21 “Si no la haces, ¿de qué vives? Le vamos a enseñar poco tlapaneco”: Un desplazamiento lingüístico en proceso entre migrantes mi’phaa (tlapanecos de Tlacoapa) en Tlaquepaque, Jalisco, México1∗ “If you don’t make it, how will you live by? We’re going to teach him a little Tlapaneco”: A language shift in progress among Mi’phaa immigrants (Tlacoapa Tlapanecs) in Tlaquepaque, Jalisco, Mexico Daniel Barragán Trejo2** Resumen Basado en observaciones participantes, un grupo focal y entrevistas etnográfi- cas a quince migrantes mi’phaa (tlapanecos de Tlacoapa, Guerrero, México) en Tlaquepaque (municipio del Área Metropolitana de Guadalajara, Jalisco, México), este artículo sostiene que no son los factores extralingüísticos per se -como la migración-, sino las reacciones de los hablantes a esos factores las que promue- ven el desplazamiento lingüístico. -

Language EI Country Genetic Unit Speakers RI Acatepec Tlapanec 5

Language EI Country Genetic Unit Speakers RI Acatepec Tlapanec 5 Mexico Subtiapa-Tlapanec 33000 1 Alacatlatzala Mixtec 4.5 Mexico Mixtecan 23000 2 Alcozauca Mixtec 5 Mexico Mixtecan 10000 3 Aloápam Zapotec 4 Mexico Zapotecan 2100 4 Amatlán Zapotec 5 Mexico Zapotecan 6000 5 Amoltepec Mixtec 3 Mexico Mixtecan 6000 6 Ascunción Mixtepec Zapotec 1 Mexico Zapotecan 100 7 Atatláhuca Mixtec 5 Mexico Mixtecan 8300 8 Ayautla Mazatec 5 Mexico Popolocan 3500 9 Ayoquesco Zapotec 3 Mexico Zapotecan < 900 10 Ayutla Mixtec 5 Mexico Mixtecan 8500 11 Azoyú Tlapanec 1 Mexico Subtiapa-Tlapanec < 680 12 Aztingo Matlatzinca 1 Mexico Otopamean > < 100 13 Matlatzincan Cacaloxtepec Mixtec 2.5 Mexico Mixtecan < 850 14 Cajonos Zapotec 4 Mexico Zapotecan 5000 15 Central Hausteca Nahuatl 5 Mexico Uto-Aztecan 200000 16 Central Nahuatl 3 Mexico Uto-Aztecan 40000 17 Central Pame 4 Mexico Pamean 4350 18 Central Puebla Nahuatl 4.5 Mexico Uto-Aztecan 16000 19 Chaopan Zapotec 5 Mexico Zapotecan 24000 20 Chayuco Mixtec 5 Mexico Mixtecan 30000 21 Chazumba Mixtec 2 Mexico Mixtecan < 2,500 22 Chiapanec 1 Mexico Chiapanec-Mangue < 20 23 Chicahuaxtla Triqui 5 Mexico Mixtecan 6000 24 Chichicapan Zapotec 4 Mexico Zapotecan 4000 25 Chichimeca-Jonaz 3 Mexico Otopamean > < 200 26 Chichimec Chigmecatitlan Mixtec 3 Mexico Mixtecan 1600 27 Chiltepec Chinantec 3 Mexico Chinantecan < 1,000 28 Chimalapa Zoque 3.5 Mexico Zoque 4500 29 Chiquihuitlán Mazatec 3.5 Mexico Popolocan 2500 30 Chochotec 3 Mexico Popolocan 770 31 Coatecas Altas Zapotec 4 Mexico Zapotecan 5000 32 Coatepec Nahuatl 2.5 -

Principales Resultados De La Encuesta Intercensal 2015. Guerrero

Principales resultados de la Encuesta Intercensal 2015 Guerrero Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía Principales resultados de la Encuesta Intercensal 2015 Guerrero Obras complementarias publicadas por el INEGI sobre el tema: Principales resultados de la Encuesta Intercensal 2015 Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Catalogación en la fuente INEGI: 304.601072 Encuesta Intercensal (2015). Principales resultados de la Encuesta Intercensal 2015 : Guerrero / Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía.-- México : INEGI, c2015. xiv, 97 p. ISBN 978-607-739-771-7 . 1. Guerrero - Población - Encuestas, 2015. I. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (México). Conociendo México 01 800 111 4634 www.inegi.org.mx [email protected] INEGI Informa @INEGI_INFORMA DR © 2016, Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía Edificio Sede Avenida Héroe de Nacozari Sur 2301 Fraccionamiento Jardines del Parque, 20276 Aguascalientes, Aguascalientes, Aguascalientes, entre la calle INEGI, Avenida del Lago y Avenida Paseo. de las Garzas. Presentación El Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI), como organismo autónomo responsable por ley de coordinar y dirigir el Sistema Nacional de Información Estadística y Geográfica, se encarga de producir y difundir información de interés nacional. Bajo esta premisa, en el 2015 se levanta una encuesta de cobertura temática amplia, denominada Encuesta Intercensal 2015, que tiene como objetivo generar información estadística actualizada sobre la población y las viviendas del territorio nacional, que mantenga la comparabilidad histórica con los censos y encuestas nacionales, así como con indicadores de otros países. Atendiendo a lo anterior, el INEGI ha puesto al alcance de todo públi- co algunos productos derivados de la Encuesta Intercensal 2015, como: Microdatos, Tabulados básicos, Presentación de resultados y Panorama sociodemográfico de México 2015.