The Challenge of Moral Difference : a Theoretical Investigation of Encounters with a Client's Capacity for Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

2006 November Family Room Schedule

NOVEMBER 2006 PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE FAMILY ROOM Time 10/30/06 - Mon 10/31/06 - Tue 11/01/06 - Wed 11/02/06 - Thu 11/03/06 - Fri 11/04/06 - Sat 11/05/06 - Sun Time THE LIVING FOREST FLIPPER 6:00 AM CONT'D (4:50 AM) DARK HORSE KAYLA CONT'D (5:45 AM) RADIO FLYER 6:00 AM TV-PG CONT'D (5:40 AM) CONT'D (5:40 AM) TV-G CONT'D (5:30 AM) FLIPPER UFO A DOLPHIN IN TIME 6:30 AM A QUESTION OF PRIORITIES 6:15 AM 6:30 AM 6:15 AM G 7:00 AM PG MAGIC OF THE GOLDEN BEAR: GOLDY III 7:00 AM TRADING MOM TV-PG TV-PG 6:40 AM TV-PG THE THUNDERBIRDS THE THUNDERBIRDS THE THUNDERBIRDS 7:30 AM 7:05 AM TRAPPED IN THE SKY PIT OR PERIL SUN PROBE 7:30 AM 7:20 AM 7:20 AM 7:25 AM 8:00 AM 8:00 AM TV-G PG TV-PG TV-PG TV-PG FLIPPER FLIPPER AND THE FUGITIVE (1) UFO THE THUNDERBIRDS UFO 8:30 AM 8:30 AM STOLEN SUMMER THE RESPONSIBILITY SEAT CITY OF FIRE COURT MARTIAL 8:30 AM TV-G 8:15 AM 8:15 AM 8:25 AM 8:15 AM FLIPPER FLIPPER AND THE FUGITIVE (2) 9:00 AM 8:55 AM TV-PG TV-Y7-FV 9:00 AM TV-G OLD SETTLERTV-PG HAMMERBOY UFO 9:30 AM THE LIVING FOREST TV-G 9:05 AM THE SQUARE TRIANGLE 9:05 AM 9:30 AM FLIPPER MOST EXPENSIVE SARDINE IN THE WORLD 9:20 AM 9:50 AM 9:20 AM 10:00 AM TV-G TV-G 10:00 AM FLIPPER FLIPPER AND THE SEAL 10:15 AM TV-G LIL ABNER TV-G FLIPPER FLIPPER DOLPHINS DON'T SLEEP THE FIRING LINE (1) 10:30 AM PG 10:30 AM 10:10 AM 10:20 AM 10:30 AM TV-PG DARK HORSE TV-G TV-G FLIPPER FLIPPER THE THUNDERBIRDS AUNT MARTHA THE FIRING LINE (2) 11:00 AM OPERATION CRASH DIVE 10:40 AM 11:00 AM 10:50 AM 11:00 AM 10:45 AM TV-PG-V TV-PG THE THUNDERBIRDS 11:30 AM TV-PG KAYLA SUN PROBE 11:30 -

Nato Standard Atp/Mtp-57 the Submarine Search and Rescue Manual

NATO STANDARD ATP/MTP-57 THE SUBMARINE SEARCH AND RESCUE MANUAL Edition C Version 2 NOVEMBER 2015 NORTH ATLANTIC TREATY ORGANIZATION ALLIED/MULTINATIONAL TACTICAL PUBLICATION Published by the NATO STANDARDIZATION OFFICE (NSO) © NATO/OTAN INTENTIONALLY BLANK NORTH ATLANTIC TREATY ORGANISATION (NATO) NATO STANDARDIZATION OFFICE (NSO) NATO LETTER OF PROMULGATION 25 November 2015 1. The enclosed Allied/Multinational Tactical Publication, ATP/MTP-57, Edition C, Version 2, THE SUBMARINE SEARCH AND RESCUE MANUAL, has been approved by the nations in the Military Committee Maritime Standardization Board and is promulgated herewith. The agreement of nations to use this publication is recorded in STANAG 1390. 2. ATP/MTP-57, Edition C, Version 2, is effective upon receipt and supersedes ATP-57; Edition C, Version 1 which shall be destroyed in accordance with the local procedure for the destruction of documents. 3. No part of this publication may be reproduced , stored in a retrieval system, used commercially, adapted, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. With the exception of commercial sales, this does not apply to member or partner nations, or NATO commands and bodies. 4. This publication shall be handled in accordance with C-M (2002)60. Edvardas MAZEIKIS Major General, LTUAF Director, NATO Standardization Office INTENTIONALLY BLANK ATP/MTP-57 RESERVED FOR NATIONAL LETTER OF PROMULGATION Edition (C) Version (2) I ATP/MTP-57 INTENTIONALLY BLANK Edition (C) Version (2) II ATP/MTP-57 RECORD OF RESERVATIONS CHAPTER RECORD OF RESERVATION BY NATIONS 1-7 TURKEY 2 ESTONIA 1-7 LATVIA Note: The reservations listed on this page include only those that were recorded at time of promulgation and may not be complete. -

The Folklore of UFO Narratives

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 5-2012 Saucers and the Sacred: The Folklore of UFO Narratives Preston C. Copeland Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Copeland, Preston C., "Saucers and the Sacred: The Folklore of UFO Narratives" (2012). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 149. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/149 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies, School of 1-1-2012 Saucers and the Sacred: The olF klore of UFO Narratives Preston C. Copeland Utah State University Recommended Citation Copeland, Preston C., "Saucers and the Sacred: The oF lklore of UFO Narratives" (2012). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. Paper 149. http://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/149 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, School of at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SAUCERS AND THE SACRED: THE FOLKLORE OF UFO NARRATIVES By Preston C. Copeland A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Of MASTER OF SCIENCE In AMERICAN STUDIES UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2012 1 PRESTON COPELAND RATIONAL UFOLOGY: THE RITES OF PASSAGE IN ALIEN ABDUCTION NARRATIVES. -

Ufo Investigations in Cold War America, 1947-1977 Kate Dorsch University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Reliable Witnesses, Crackpot Science: Ufo Investigations In Cold War America, 1947-1977 Kate Dorsch University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Dorsch, Kate, "Reliable Witnesses, Crackpot Science: Ufo Investigations In Cold War America, 1947-1977" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3231. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3231 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3231 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reliable Witnesses, Crackpot Science: Ufo Investigations In Cold War America, 1947-1977 Abstract This dissertation explores efforts to design and execute scientific tuds ies of unidentified flying objects (UFOs) in the United States in the midst of the Cold War as a means of examining knowledge creation and the construction of scientific uthora ity and credibility around controversial subjects. I begin by placing officially- sanctioned, federally-funded UFO studies in their appropriate context as a Cold War national security project, specifically a project of surveillance and observation, built on traditional arrangements within the military- industrial-academic complex. I then show how non-traditional elements of the investigations – the reliance on non-expert witnesses to report transient phenomena – created space for dissent, both within the scientific establishment and among the broader American public. By placing this dissent within the larger social and political instability of the mid-20th century, this dissertation highlights the deep ties between scientific knowledge production and the social value and valence of professional expertise, as well as the power of experiential expertise in challenging formal, hegemonic institutions. -

UFO Part 12 of 16

q e 0 -v ; - 9 . - I u _; am-menu cnunrv 3 i DEPARTMENT DF CIVIL DEFENSE E annulus AND oaexaou eraana } . FRANKLIN, INDIANA u spec-see-s '- n_"" '92 ' IO January 195$ .~~. - " $5!-" Ill. J. Edgar Hoover a Washington,Director ?ederal C.Bureau of D.Investigation 92 I l E V. 2 DIM Bil: . , . - I would first like to apologise for writing to you direct, however, I have V oleared this morning;with our Itote Director and he auggests this procedure. 1 i WeI tour !have posts beenherehaving the inacne successoount_!';_{7 withif/F_ our Ground Ctservation / Corps- q'...;_--.-/i_, as we have- . Inst Fall I was contacted byor;e"oi"our local business mniEt'i§'t'o'11E'owif I would be interested inJoining; internaticnalFlying SaucerBureau. I told bin 1 that I would and did joinwith the idea fully inlind oihaving thelocal people Iho are interested in Flying Saucers also work in our Civil Defense Program. Io are , only too willing -to co-operate in any my we can iith civil Defense. Ihe city or ' iranklin is approximately twenty 0! niles southwest of Indianapolis, on the dual ' lane highway o s #51. 92 I am enclosing a letter which wns received.last October, as well as the current 'issue ' oi/T."l'I.C'£ Iould like to know if this organisationhas beencleared or i_s___:ubvers'i';§'in any way. ' "" '""-'--'- . I would appreciate your expediting this information back to us so that we will know shat steps to take in further enlisting interested persons in our program. -

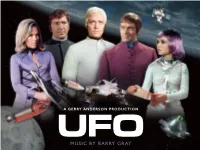

Gerry Anderson's PREMISE: in the Late 1960S, the United States

Gerry Anderson’s UFO PREMISE: In the late 1960s, the United States government issued a report officially denying the existence of Unidentified Flying Objects. The government agencydesigned to look into the phenomenon, Project Blue Book, was also closed down and people were led to believe that (as far as the government was concerned) UFOs had not come to Earth. The format of the television series takes this occurrence as a cover-up by the government in an attempt to hide the fact that we were not only visited by creatures from space, but brutally attacked. Their reasoning was that mass hysteria and panic would result if the common man discovered that his world was being invaded by extraterrestrials. So, in secret, the major governments of the world created SHADO − Supreme Headquarters, Alien Defense Organi- zation. From it’scenter of operations hidden beneath a film studio (where bizarre comings and goings would remain commonplace), SHADO commands a fleet of submarines (armed with sea-to-air strikecraft), aircraft, land vehicles, satellites and a base on the Moon. MAJOR CHARACTERS: COMMANDER ED STRAKER−Leader of SHADO. He is totally dedicated to his job, almost to the point of obsession. COLONEL ALEC FREEMAN−Straker’ssecond-in-command. COLONEL PAULFOSTER−Former test pilot recruited to SHADO. CAPTAIN PETER CARLIN−Commander and interceptor pilot of Skydiver1. MISS EALAND−Straker’ssecretary for his film studio president cover. LT . MARK BRADLY−Moonbase interceptor pilot. LT . LEW WATERMAN−Moonbase interceptor pilot, later promoted to SkydiverCaptain. LT . JOAN HARRINGTON−Moonbase Operative. LT . FORD−SHADO Control Radio Operator LT . GAYELLIS−Moonbase Commander COLONEL VIRGINIA LAKE−Designer of the Utronic tracking equipment needed to detect UFOs in flight. -

MUSIC by BARRY GRAY the Earth Is Faced with a Power Threat from an Dateline:1980 EXTRATERRESTRIAL Source

A GERRY ANDERSON PRODUCTION UFO MUSIC BY BARRY GRAY The Earth is faced with a power threat from an Dateline:1980 EXTRATERRESTRIAL source... we have moved After a decade of creating pioneering puppet series made for children, the Andersons took their first into an age where SCIENCE FICTION has become steps into live-action, with the 1969 feature film FACT. We need to DEFEND ourselves. Doppelgänger (re-titled outside Britain as Journey To The Far Side Of The Sun). This science-fiction film COMMANDER ED STRAKER approached its outer space subject matter with a gritty realism, and would set the tone for what was to be their first live-action television series:UFO . This new series took as a starting point the pioneering work of Dr Christiaan N. Barnard, the surgeon who performed the world’s first heart transplant operation. In UFO a dying race of aliens travel across vast distances of space to harvest organs from human beings to help ensure their own survival. To combat this threat the United Nations created SHADO, a top-secret organisation utilising the latest technology available to defend the Earth. To complement the series, the Andersons frequent musical collaborator Barry Gray created a multifaceted score that gave the programme its own musical identity. This Album is the very first commercial release of Gray’s score, making it finally available to more listeners worldwide. Welcome to SHADO SHADO – Supreme Headquarters Alien Defence Organisation – is based from a secret headquarters deep beneath the Harlington Straker Film Studio. Earth’s first line of defence is SID, the Space Intruder Detector, a satellite in Earth’s orbit created to spot incoming UFOs. -

The Military Contribution to the Prevention of Violent Con Ict

Understand to Prevent The military contribution to the prevention of violent con ict MCDC November 2014 10532_MOD U2P B5 PRINT_cover v0_2.indd All Pages 25/03/2015 10:29 Understand to Prevent The military contribution to the prevention of violent conflict A Multinational Capability Development Campaign project Project Team: GBR, AUT, CAN, FIN, NLD, NOR, USA November 2014 Distribution statement This document was developed and written by the contributing nations and international organizations of the Multinational Capability Development Campaign (MCDC) 2013-14. The 23 partner nations and international governmental organizations that make up MCDC are a coalition of the willing that collaborate to develop and enhance interoperability while maximising benefits of resource and cost sharing. The products developed provide a common foundation for national and organizational capability development in the areas of interoperability, doctrine, organization, training, leadership education, personnel and policy. This document does not necessarily reflect the official views or opinions of any single nation or organization, but is intended as recommendations for national/international organizational consideration. Reproduction of this document is authorized for personal and non-commercial use only, provided that all copies retain the author attribution as specified below. The use of this work for commercial purposes is prohibited; its translation into other languages and adaptation/ modification requires prior written permission. Questions, comments and requests for information can be referred to: [email protected] Preface — A new focus Military thinking on the utility of force is at a In practical terms, while warfighting will always crossroads. Thirteen years of continuous remain the foundation of military capability, we warfare — in Iraq, Afghanistan and the brief need to supplement the current spectrum of intervention in Libya — have delivered only effects practised by most Western nations limited and uncertain political gains. -

The Way out Invisible Insurrections and Radical Imagi- Naries in the UK Underground 1961-1991

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output The way out invisible insurrections and radical imagi- naries in the UK underground 1961-1991 https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40068/ Version: Full Version Citation: Frederiksen, Kasper Opstrup (2014) The way out invisible in- surrections and radical imaginaries in the UK underground 1961-1991. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email The Way Out Invisible Insurrections and Radical Imaginaries in the UK Underground 1961-1991 Kasper Opstrup Frederiksen PhD Humanities and Cultural Studies Birkbeck College University of London 1 Declaration of Authorship: I hereby declare that, except where explicit attribution is made, this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. ________________________________________________ Kasper Opstrup Frederiksen 2 Abstract This thesis explores a 'hidden' cultural history of experiments to engineer culture to transform humanity. Through a mixture of ideas drawn from artistic avant-garde movements as well as new social and religious movements, it examines the radical political and hedonist imaginaries of the experimental fringes of the UK Underground. Even though the theatres of operation have changed more than once since 1991 with the rise of the internet and a globalised finance economy, these imaginaries still raise questions that speak directly to the contemporary. My central inquiry examines the relations between collective practices with an explicit agenda of cultural revolution and discourses of direct revolutionary action, cultural guerrilla warfare and patchwork spirituality, all aiming to generate new forms of social life. -

Grand County Council Chambers 125 East Center Street, Moab, Utah

GRAND COUNTY COUNCIL REGULAR MEETING Grand County Council Chambers 125 East Center Street, Moab, Utah AGENDA Tuesday, May 7, 2013 4:00 p.m. Call to Order Pledge of Allegiance Approval of Minutes (Diana Carroll, Clerk/Auditor) A. March 29, 2013 (Joint City/County Council Meeting) B. April 2, 2013 (County Council Meeting) C. April 5, 2013 (Special Meeting: Council Administrative Workshop) D. April 9, 2013 (Special Meeting: Council Administrative Workshop) E. April 16, 2013 (County Council Meeting) F. April 17, 2013 (Special Meeting: Council Administrative Workshop) G. April 30, 2013 (Special Meeting: Council Administrative Workshop) Ratification of Payment of Bills Elected Official Reports Council Administrator Report Department Head Reports H. 2012 Annual Travel Council Report (Marian DeLay, Executive Director, Moab Area Travel Council) Agency Reports Citizens to Be Heard Presentations I. Presentation of 2013 Grand County, Utah Silver Bowl Award for Exemplary Volunteer Work (Saina Carey, Silver Bowl Committee Chairman) J. Presentation on American Lands Council Growth and Community Involvement (Kane County Commissioner Doug Heaton) Discussion Items K. Discussion of Local Business Letter to Congressman Bishop Regarding Proposed Public Lands Bill (Colin Fryer, Red Cliffs Lodge; Scott Guzman Newton, Poison Spider Bike Shop; Doug Sorenson, Portal RV; and Ashley Korenblat, Western Spirit Cycling) L. Discussion on Sending Requests for Proposals to Energy Services Companies (ESCO’s) to Provide Budget-Neutral Energy Efficiency Improvements to County Buildings (Ruth Dillon, Council Administrator) M. Calendar Items and Public Notices (KaLeigh Welch, Council Office Coordinator) General Business- Action Items N. Approving Bid Award for the Installation of High Density Mineral Bond Seal and Striping on Selected Portions of Grand County’s Paved Pathways (Bill Jackson, Roads Supervisor) O. -

How Cultural Representations of Alien Abduction Support an Entrenched Consensus Reality

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Frederick Clark Bryan for the degree of Master of Arts in English presented on August 10, 1998. Title: Aliens and Academics: How Cultural Representations of Alien Abduction Support an Entrenched Consensus Reality. Abstract approved: Redacted for Privacy Jon Lewis The alien abduction phenomenon has garnered considerable media attention in the last fifteen years, including many representations in books, film, and television.An overview of significant abduction literature is presented. Contrasts and comparisons are noted between popular written accounts and both the visual representations they engender and reports outside the mainstream, such as those compiled and statistically compared by folklorists. Also considered are comparisons between popular fictionalizations of victims of abduction and the relevant psychological literature on this population. Theories bordering on the psycho-spiritual and New Age are briefly introduced in regards to their connection to UFO phenomena and the popular belief in a changing collective consciousness. Throughout, it is argued that most forms of cultural production featuring themes of alien abduction, being subject to marketplace demand, alter or fictionalize their source content for dramatic purposes. This popularization and commodification of anomalous phenomena negatively impacts serious study by encouraging dismissive attitudes towards evidence, reports, and those individuals involved, informants, victims, and investigators. This commodification thus serves to protect the