Dennis Miller's Ranting Rhetorical Persona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

07 Soccerw Guide.Pmd

CALIFORNIA Golden Bears 2007 GOLDEN BEAR SOCCER CAL QUICK FACTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Location ......................... Berkeley, CA 94720 Founded ............................................... 1868 Cal Campus ............................................ IFC Cal Records ....................................... 16-17 Enrollment .......................................... 33,000 Quick Facts/Media Contacts ...................... 1 Honors and Awards .......................... 18-19 Conference ................................... Pacific-10 2007 Outlook ............................................. 2 Year-By-Year Results/Postseason ... 20-23 Nickname ................................. Golden Bears 2007 Roster .............................................. 3 Cal vs. All Opponents ............................. 21 Colors ......................................... Blue & Gold 2007 Athlete Profiles............................ 4-10 The University of California ................ 24-25 Chancellor ......................... Robert Birgeneau Cal Coaching Staff ............................. 11-12 Academic Support/Strength Program ...... 26 Director of Athletics .............. Sandy Barbour Opponents .............................................. 13 Administration Bios ................................. 27 Asst. AD/Women’s Soccer ..............Liz Miles 2006 Season In Review/ Edwards Stadium/Goldman Field ............. 28 Home Field/Capacity ............... Goldman Field Pac-10 Standings .................................... 14 Bears Up Close ..................................... -

Quotes from Co-Signers of Garrett's Iran Letter to President

QUOTES FROM CO-SIGNERS OF GARRETT’S IRAN LETTER TO PRESIDENT BUSH Walter Jones ● Authored A Letter With Democrat Rep. Keith Ellison Encouraging Negotiations With Iran In 2012, Jones Signed A Letter With Democrat Rep. Keith Ellison (D-MN) Encouraging Negotiations With Iran. “We strongly encourage your Administration to pursue bilateral and multilateral engagement with Iran. While we acknowledge that progress will be difficult, we believe that robust, sustained diplomacy is the best option to resolve our serious concerns about Iran's nuclear program, and to prevent a costly war that would be devastating for the United States and our allies in the region.” (Walter B. Jones and Keith Ellison, Letter, 3/2/12) ● Extreme Minority Of House Members To Vote Against Additional Sanctions On Iran In 2012, The House Passed Additional Sanctions Against Iran's Energy, Shipping, and Insurance Sectors. “Both houses of Congress approved legislation on Wednesday that would significantly tighten sanctions against Iran's energy, shipping and insurance sectors. The bill is the latest attempt by Congress to starve Iran of the hard currency it needs to fund what most members agree is Iran's ongoing attempt to develop a nuclear weapons program.” (Pete Kasperowicz, “House, Senate Approve Tougher Sanctions Against Iran, Syria,” The Hill's Floor Action, 8/1/12) One Of Only Six House Members To Vote Against The 2012 Sanctions Bill. “The sanctions bill was approved in the form of a resolution making changes to prior legislation, H.R. 1905, on which the House and Senate agreed — it passed in an 421-6 vote, and was opposed by just five Republicans and one Democrat. -

Giuliani, 9/11 and the 2008 Race

ABC NEWS/WASHINGTON POST POLL: ‘08 ELECTION UPDATE EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE AFTER 11:35 p.m. Tuesday, Sept. 11, 2007 Giuliani, 9/11 and the 2008 Race Six years after the terrorist attacks that vaulted him to national prominence, it’s unclear whether 9/11 will lift Rudy Giuliani all the way to the presidency: He remains hamstrung in the Republican base, and his overall support for his party’s nomination has slipped in the latest ABC News/Washington Post poll. Giuliani does better with Republicans who are concerned about another major terrorist attack in this country, a legacy of his 9/11 performance. But among those less focused on terrorism, he’s in a dead heat against newcomer Fred Thompson. Thompson also challenges Giuliani among conservatives and evangelical white Protestants – base groups in the Republican constituency – while John McCain has stabilized after a decline in support. Giuliani still leads, but his support is down by nine points in this poll from his level in July. Indeed this is the first ABC/Post poll this cycle in which Giuliani had less than a double- digit lead over all his competitors: He now leads Thompson by nine points (and McCain by 10). Among Republicans and Republican-leaning independents, 28 percent support Giuliani, 19 percent Thompson, 18 percent McCain and 10 percent Mitt Romney. Other candidates remain in the low single digits. (There’s no significant difference among registered voters – and plenty of time to register.) ’08 Republican primary preferences Now July June April Feb Giuliani 28% 37 34 35 53 Thompson 19 15 13 10 NA McCain 18 16 20 22 23 Romney 10 8 10 10 5 The Democratic race, meanwhile, remains exceedingly stable; Hillary Clinton has led Barack Obama by 14 to 16 points in each ABC/Post poll since February, and still does. -

1 in the United States District Court for the District

6:10-cv-01884-JMC Date Filed 07/20/10 Entry Number 1 Page 1 of 23 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA GREENVILLE DIVISION TIM CLARK, JOHANNA CLOUGHERTY, CIVIL ACTION MICHAEL CLOUGHERTY, on behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated, Plaintiffs, v. CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT GOLDLINE INTERNATIONAL, INC., Defendant. I. NATURE OF THE ACTION 1. Plaintiffs and proposed class representatives Tim Clark, Johanna Clougherty, and Michael Clougherty (“Plaintiffs”) bring this action individually and on behalf of all other persons similarly situated against Defendant Goldline International, Inc. (“Goldline”) to recover damages arising from Goldline’s violation of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (“RICO”), 18 U.S.C. § 1961, et seq., unfair and deceptive trade practices, and unjust enrichment. 2. This action is brought as a class action pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23 on behalf of a Class, described more fully below, which includes all persons or entities domiciled or residing in any of the fifty states of the United States of America or in the District of Columbia who purchased at least one product from Goldline since July 20, 2006. 3. Goldline is a precious metal dealer that buys and sells numismatic coins and bullion to investors and collectors all across the nation via telemarketing and telephone sales. Goldline is an established business that has gained national prominence in recent years through its association with conservative talk show hosts it sponsors and paid celebrity spokespeople who 1 6:10-cv-01884-JMC Date Filed 07/20/10 Entry Number 1 Page 2 of 23 have agreed to promote Goldline products by playing off the fear of inflation to encourage people to purchase gold and other precious metals as an investment that will protect them from an out of control government. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

From UD! It's Dennis Miller!

University of Dayton eCommons News Releases Marketing and Communications 3-31-1989 Live! From UD! It's Dennis Miller! Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/news_rls Recommended Citation "Live! From UD! It's Dennis Miller! " (1989). News Releases. 5256. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/news_rls/5256 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marketing and Communications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in News Releases by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The University gf Dayton News Release LIVE! FROM UD! IT'S DENNIS MILLER! DAYTON, Ohio, March 31, 1989--Comedian Dennis Miller, anchorman for the Weekend Update on the long-running TV series "Saturday Night Live," will perform at the University of Dayton on Saturday, April 8 at 8 p.m. in the UD Fieldhouse. Opening the show will be "HBO Young Comedian of the Year" Gary Lazer. General admission tickets for "An Evening with Dennis Miller" are $9 and are available at all Ticketron outlets. The performance is sponsored by UD's Student Government Association. Miller writes for many skits featured on "Saturday Night Liye" in addition to writing and performing the Weekend Update segments. A four-year veteran of the show, Miller has also appeared in "Mr. Miller Goes to Washington," a comedy special on HBO, and is active in the Comic Relief effort for the homeless. He fine-tuned his political and· topical humor as a stand-up comic in New York and California before joining the SNL cast. -

1 Who Brings the Funny? 3 Mirroring the Political Climate: Satire in History

Notes 1 Who Brings the Funny? 1 . Obscenity, incitement to violence, and threatening the life of the president are several examples of restrictions on expression. 2 . There have been several cases of threats against political cartoonists and comedians made by Islamic extremists who felt their religion was being mocked. These examples include (but are not limited to) the Danish political cartoonist who drew a depiction of the Prophet Mohammed, the creators of South Park who pretended to, and David Letterman who mocked Al Qaida. 3 Mirroring the Political Climate: Satire in History 1 . I urge readers to review K. J. Dover’s (1974) and Jeffrey Henderson’s (1980) work on Aristophanes, and see Peter Green (1974) and Susanna Morton Braund (2004). Other work on Juvenal includes texts by Gilbert Highet (1960) and J. P. Sullivan (1963). I have also been directed by very smart people to Ralph M. Rosen, Making Mockery: The Poetics of Ancient Satire, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2 0 0 7 ) . 2 . Apparently, the “definitive” Pope prose is found in the volume edited by Ault and Cowler (Oxford: Blackwell, 1936–1986), and the “definitive” text for Gay’s poetry is edited by Dearing (Oxford: Clarendon, 1974). 3. The best collection from Swift comes from Cambridge Press: English Political Writings 1711–1714, edited by Goldgar (2008). Thanks to Dr. Sharon Harrow for her assistance in finding this authoritative resource. 4 . The most authoritative biographies of Franklin are from Isaacson (2003) and Brands (2002), and I recommend readers look to these two authors for more information on one of the most fascinating of our founding fathers. -

Storm May Bring Snow to Valley Floor

Mendo women Rotarians plan ON THE MARKET fall to Solano Super Bowl bash Guide to local real estate .............Page A-6 ............Page A-3 ......................................Inside INSIDE Mendocino County’s Obituaries The Ukiah local newspaper ..........Page 2 Tomorrow: Rain High 45º Low 41º 7 58551 69301 0 FRIDAY Jan. 25, 2008 50 cents tax included DAILY JOURNAL ukiahdailyjournal.com 38 pages, Volume 149 Number 251 email: [email protected] Storm may bring snow to valley floor By ZACK SAMPSEL but with low pressure systems from and BEN BROWN Local agriculture not expected to sustain damage the Gulf of Alaska moving in one The Daily Journal after another the cycle remains the A second round of winter storms the valley floor, but the weather is not the county will experience scattered ing routine for some Mendocino same each day. lining up to hit Mendocino County expected to be a threat to agriculture. showers today with more mountain County residents. The previous low pressure system today is expected to bring more rain, According to reports from the snow to the north in higher eleva- Slight afternoon warmups have cold temperatures and snow as low as National Weather Service, most of tions, which has been the early-morn- helped to make midday travel easier, See STORM, Page A-12 GRACE HUDSON MUSEUM READIES NEW EXHIBIT Kucinich’s wife cancels planned stop in Hopland By ROB BURGESS The Daily Journal Hey, guess what? Kucinich quits Elizabeth Kucinich is coming to Mendocino campaign for County. Wait. Hold on. No, White House actually she isn’t. Associated In what should be a Press familiar tale to perennial- Democrat ly disappointed support- Dennis Kuci- ers of Democratic presi- nich is aban- dential aspirant Rep. -

Union Calendar No. 603

Union Calendar No. 603 110TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 110–930 ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST AND SECOND SESSIONS 2007–2008 Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/ index.html http://www.house.gov/reform JANUARY 2, 2009.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed VerDate Aug 31 2005 01:57 Jan 03, 2009 Jkt 046108 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6012 Sfmt 6012 E:\HR\OC\HR930.XXX HR930 smartinez on PROD1PC64 with REPORTS congress.#13 ACTIVITIES REPORT OF THE HOUSE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM VerDate Aug 31 2005 01:57 Jan 03, 2009 Jkt 046108 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 E:\HR\OC\HR930.XXX HR930 smartinez on PROD1PC64 with REPORTS with PROD1PC64 on smartinez 1 Union Calendar No. 603 110TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 110–930 ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST AND SECOND SESSIONS 2007–2008 Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/ index.html http://www.house.gov/reform JANUARY 2, 2009.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 46–108 WASHINGTON : 2009 VerDate Aug 31 2005 01:57 Jan 03, 2009 Jkt 046108 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HR930.XXX HR930 smartinez on PROD1PC64 with REPORTS congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM HENRY A. -

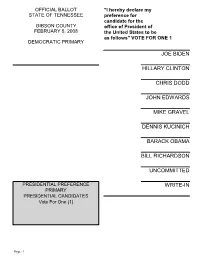

Joe Biden Hillary Clinton Chris Dodd John Edwards Mike Gravel Dennis Kucinich Barack Obama Bill Richardson Uncommitted Write-In

OFFICIAL BALLOT "I hereby declare my STATE OF TENNESSEE preference for candidate for the GIBSON COUNTY office of President of FEBRUARY 5, 2008 the United States to be as follows" VOTE FOR ONE 1 DEMOCRATIC PRIMARY JOE BIDEN HILLARY CLINTON CHRIS DODD JOHN EDWARDS MIKE GRAVEL DENNIS KUCINICH BARACK OBAMA BILL RICHARDSON UNCOMMITTED PRESIDENTIAL PREFERENCE WRITE-IN PRIMARY PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES Vote For One (1) Page: 1 PROPERTY ASSESSOR Vote For One (1) MARK CARLTON JOSEPH F. HAMMONDS JOHN MCCURDY GARY F. PASCHALL WRITE-IN Page: 2 OFFICIAL BALLOT "I hereby declare my STATE OF TENNESSEE preference for candidate for the GIBSON COUNTY office of President of FEBRUARY 5, 2008 the United States to be as follows" VOTE FOR ONE 1 REPUBLICAN PRIMARY RUDY GIULIANI MIKE HUCKABEE DUNCAN HUNTER ALAN KEYES JOHN MCCAIN RON PAUL MITT ROMNEY TOM TANCREDO FRED THOMPSON PRESIDENTIAL PREFERENCE UNCOMMITTED PRIMARY PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES Vote For One (1) WRITE-IN Page: 3 THE FOLLOWING OFFICE Edna Elaine Saltsman CONTINUES ON PAGES 2-5 John Bruce Saltsman, Sr. DELEGATES AT LARGE John "Chip" Saltsman, Jr. Committed and Uncommitted Vote For Twelve (12) Kari H. Smith MIKE HUCKABEE Michael L. Smith Emily G. Beaty Windy J. Smith Robert Arthur Bennett JOHN MCCAIN H.E. Bittle III Todd Gardenhire Beth G. Cox Justin D. Pitt Kenny D. Crenshaw Melissa B. Crenshaw Dan L. Hardin Cynthia H. Murphy Deana Persson Eric Ratcliff CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE Page: 4 DELEGATES AT LARGE Matthew Rideout Committed and Uncommitted Vote For Twelve (12) Mahmood (Michael) Sabri RON PAUL Cheryl Scott William M. Coats Joanna C. -

Politics of Parody

Bryant University Bryant Digital Repository English and Cultural Studies Faculty English and Cultural Studies Journal Articles Publications and Research Winter 2012 Live From New York, It's the Fake News! Saturday Night Live and the (Non)Politics of Parody Amber Day Bryant University Ethan Thompson Texas A & M University - Corpus Christi, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bryant.edu/eng_jou Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Recommended Citation Day, Amber and Thompson, Ethan, "Live From New York, It's the Fake News! Saturday Night Live and the (Non)Politics of Parody" (2012). English and Cultural Studies Journal Articles. Paper 44. https://digitalcommons.bryant.edu/eng_jou/44 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English and Cultural Studies Faculty Publications and Research at Bryant Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English and Cultural Studies Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Bryant Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Live from New York, It’s the Fake News! Saturday Night Live and the (Non)Politics of Parody Amber Day Assistant Professor English and Cultural Studies Bryant University 401-952-3933 [email protected] Ethan Thompson Associate Professor Department of Communication Texas A&M University - Corpus Christi 361-876-5200 [email protected] 2 Abstract Though Saturday Night Live’s “Weekend Update” has become one of the most iconic of fake news programs, it is remarkably unfocused on either satiric critique or parody of particular news conventions.