Leeds Thesis Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Among Us by Nina Runa Essendrop

1 . Among us By Nina Runa Essendrop A poetic and sensuous scenario about human loneliness and about the longing of the angels for the profound beauty which is found in every human life. 2 Preview Humans are ever present. They see the world in colors. They feel and they think and they walk on two feet. They touch the water and feel the cold softness of the surface. They gaze at the horizon and think deep thoughts about their existence. Humans feel the wind against their faces, they laugh and they cry and their pleading eyes seek for a meaning in the world around them. They breathe too fast and they forget to feel the ground under their feet or the invisible hand on their shoulder, which gently offers them comfort and peace. Angels exist among the humans. Invisible and untouchable they witness how humans live their lives. Their silent voices gently form mankind’s horizons, far away and so very very close that only children and dreamers will sense their presence. "Among us" is a poetic and sensuous scenario about a lonely human being, an angel who chooses the immediacy of mortal life, and an angel who continues to be the invisible guardian of mankind. It is a slow and thoughtful experience focussing on how beautiful, difficult and meaningful it is to be a human being. The scenario is played as a chamber larp and the players will be prepared for the play-style and tools through a workshop. The scenario is based on the film ”Wings of Desire” by Win Wender. -

Commissioned Orchestral Version of Jonathan Dove’S Mansfield Park, Commemorating the 200Th Anniversary of the Death of Jane Austen

The Grange Festival announces the world premiere of a specially- commissioned orchestral version of Jonathan Dove’s Mansfield Park, commemorating the 200th anniversary of the death of Jane Austen Saturday 16 and Sunday 17 September 2017 The Grange Festival’s Artistic Director Michael Chance is delighted to announce the world premiere staging of a new orchestral version of Mansfield Park, the critically-acclaimed chamber opera by composer Jonathan Dove and librettist Alasdair Middleton, in September 2017. This production of Mansfield Park puts down a firm marker for The Grange Festival’s desire to extend its work outside the festival season. The Grange Festival’s inaugural summer season, 7 June-9 July 2017, includes brand new productions of Monteverdi’s Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria, Bizet’s Carmen, Britten’s Albert Herring, as well as a performance of Verdi’s Requiem and an evening devoted to the music of Rodgers & Hammerstein and Rodgers & Hart with the John Wilson Orchestra. Mansfield Park, in September, is a welcome addition to the year, and the first world premiere of specially-commissioned work to take place at The Grange. This newly-orchestrated version of Mansfield Park was commissioned from Jonathan Dove by The Grange Festival to celebrate the serendipity of two significant milestones for Hampshire occurring in 2017: the 200th anniversary of the death of Austen, and the inaugural season of The Grange Festival in the heart of the county with what promises to be a highly entertaining musical staging of one of her best-loved novels. Mansfield Park was originally written by Jonathan Dove to a libretto by Alasdair Middleton based on the novel by Jane Austen for a cast of ten singers with four hands at a single piano. -

November 2, 2019 Julien's Auctions: Property From

JULIEN’S AUCTIONS: PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: JULIEN’S AUCTIONS: PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN Four-Time Grammy Award-Winning Pop Diva and Hollywood Superstar’s Iconic “Grease” Leather Jacket and Pants, “Physical” and “Xanadu” Wardrobe Pieces, Gowns, Awards and More to Rock the Auction Stage Portion of the Auction Proceeds to Benefit the Olivia Newton-John Cancer Wellness & Research Centre https://www.onjcancercentre.org NOVEMBER 2, 2019 Los Angeles, California – (June 18, 2019) – Julien’s Auctions, the world-record breaking auction house, honors one of the most celebrated and beloved pop culture icons of all time with their PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN (OBE, AC, HONORARY DOCTORATE OF LETTERS (LA TROBE UNIVERSITY)) auction event live at The Standard Oil Building in Beverly Hills and online at juliensauctions.com. Over 500 of the most iconic film and television worn costumes, ensembles, gowns, personal items and accessories owned and used by the four-time Grammy award-winning singer/Hollywood film star and one of the best-selling musical artists of all time who has sold 100 million records worldwide, will take the auction stage headlining Julien’s Auctions’ ICONS & IDOLS two-day music extravaganza taking place Friday, November 1st and Saturday, November 2nd, 2019. PAGE 1 Julien’s Auctions | 8630 Hayden Place, Culver City, California 90232 | Phone: 310-836-1818 | Fax: 310-836-1818 © 2003-2019 Julien’s Auctions JULIEN’S AUCTIONS: PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN PRESS RELEASE The Cambridge, England born and Melbourne, Australia raised singer and actress began her music career at the age of 14, when she formed an all-girl group, Sol Four, with her friends. -

The Other Tchaikowsky

The Other Tchaikowsky A biographical sketch of André Tchaikowsky David A. Ferré Cover painting: André Tchaikowsky courtesy of Milein Cosman (Photograph by Ken Grundy) About the cover The portrait of André Tchaikowsky at the keyboard was painted by Milein Cosman (Mrs. Hans Keller) in 1975. André had come to her home for a visit for the first time after growing a beard. She immediately suggested a portrait be made. It was completed in two hours, in a single sitting. When viewing the finished picture, André said "I'd love to look like that, but can it possibly be me?" Contents Preface Chapter 1 - The Legacy (1935-1982) Chapter 2 - The Beginning (1935-1939) Chapter 3 - Survival (1939-1945 Chapter 4 - Years of 'Training (1945-1957) Chapter 5 - A Career of Sorts (1957-1960) Chapter 6 - Homeless in London (1960-1966) Chapter 7 - The Hampstead Years (1966-1976) Chapter 8 - The Cumnor Years (1976-1982) Chapter 9 - Quodlibet Acknowledgments List of Compositions List of Recordings i Copyright 1991 and 2008 by David A. Ferré David A. Ferré 2238 Cozy Nook Road Chewelah, WA 99109 USA [email protected] http://AndreTchaikowsky.com Preface As I maneuvered my automobile through the dense Chelsea traffic, I noticed that my passenger had become strangely silent. When I sneaked a glance I saw that his eyes had narrowed and he held his mouth slightly open, as if ready to speak but unable to bring out the words. Finally, he managed a weak, "Would you say that again?" It was April 1985, and I had just arrived in London to enjoy six months of vacation and to fulfill an overdue promise to myself. -

NABMSA Reviews a Publication of the North American British Music Studies Association

NABMSA Reviews A Publication of the North American British Music Studies Association Vol. 5, No. 2 (Fall 2018) Ryan Ross, Editor In this issue: Ita Beausang and Séamas de Barra, Ina Boyle (1889–1967): A Composer’s Life • Michael Allis, ed., Granville Bantock’s Letters to William Wallace and Ernest Newman, 1893–1921: ‘Our New Dawn of Modern Music’ • Stephen Connock, Toward the Rising Sun: Ralph Vaughan Williams Remembered • James Cook, Alexander Kolassa, and Adam Whittaker, eds., Recomposing the Past: Representations of Early Music on Stage and Screen • Martin V. Clarke, British Methodist Hymnody: Theology, Heritage, and Experience • David Charlton, ed., The Music of Simon Holt • Sam Kinchin-Smith, Benjamin Britten and Montagu Slater’s “Peter Grimes” • Luca Lévi Sala and Rohan Stewart-MacDonald, eds., Muzio Clementi and British Musical Culture • Christopher Redwood, William Hurlstone: Croydon’s Forgotten Genius Ita Beausang and Séamas de Barra. Ina Boyle (1889-1967): A Composer’s Life. Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press, 2018. 192 pp. ISBN 9781782052647 (hardback). Ina Boyle inhabits a unique space in twentieth-century music in Ireland as the first resident Irishwoman to write a symphony. If her name conjures any recollection at all to scholars of British music, it is most likely in connection to Vaughan Williams, whom she studied with privately, or in relation to some of her friends and close acquaintances such as Elizabeth Maconchy, Grace Williams, and Anne Macnaghten. While the appearance of a biography may seem somewhat surprising at first glance, for those more aware of the growing interest in Boyle’s music in recent years, it was only a matter of time for her life and music to receive a more detailed and thorough examination. -

PDF of This Issue

Freshman Registration TodayToday MIT’s The Weather Today: Clear skies, 83ºF (28ºC) Oldest and Largest Tonight: Mild, 66ºF (19ºC) Tomorrow: Warm, 83ºF (28ºC) NewspaperThursday Details, Page 2 VolumeVolume 125, Number 34 Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Thursday,Thursday, September 1, 2005 Greenblatt Selected As Interim Exec. VP By Marie Y. Thibault who help STAFF REPORTER m e m b e r s Sherwin Greenblatt ’62 has been of the MIT named MIT’s interim executive vice community president for fi nance and administra- interested tion, taking over for departing Exec- in starting utive Vice President John R. Curry. their own President Susan Hockfi eld, who businesses. appointed Greenblatt last week, said On the in an e-mail that he “brings a wealth third day of experience in running a complex of his new operation, and, importantly, one in job, Green- MIT NEWS OFFICE which innovation is a core value.” blatt said Sherwin Greenblatt ’62 Greenblatt, currently director of it was a bit MIT’s Venture Mentoring Service, soon to talk about plans or changes he was also president of Bose Corpora- might implement. tion for 15 years. He obtained both Greenblatt said that when he bachelor’s and master’s degrees at learned he was being offered the MIT before becoming the fi rst em- position, he was “totally shocked.” ployee hired by Professor Emeritus After the news settled in, however, DAN BERSAK—THE TECH The MIT Police presented the colors at Fenway Park Tuesday night. They were the fi rst group as- Amar G. Bose ’51 at his company . he said that he realized it would be sociated with an educational institution ever to present the colors at Fenway. -

01 DESIGNER EDITIONS.Pdf

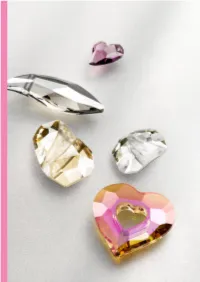

Designer Editions 01 01 DESIGNER EDITIONS Swarovski is proud of its long history of creative collaborations with artists, artisans, and designers in all fields of design – a history that continues to be written today by both esteemed established names and new bright young stars. Continually entranced by the myriad possibilities of crystal, these creatives are inspired to transform their sparkling visions into exclusive cuts and designs for SWAROVSKI ELEMENTS. Crystal is both the dream-maker and a dynamic source of inspiration for creative minds all over the world. Designer Editions Collection of Keys inspired by Yoko Ono Catalysing Imagination by exclusive Designer Edition Products <<< Designer Editions Swarovski can look back with pride on a long history of partnerships with many fashion and design legends like Coco Chanel or Christian Dior. The Aurora Borealis effect, for example, found worldwide acclaim following work with Christian Dior in the 1950s. More recently, the creative partnership with Giorgio Armani saw the development of the Diamond Leaf cut, which features an organic design and closely 01 resembles a natural leaf. Nature has also provided the inspiration for the latest joint project with the French designer Andrée Putman. These design co-operations are joyful collaborations that always result in beauty and quite unconventional displays of creativity. But Dior, Armani and Putman are just three examples of the many celebrated designers who have worked with SWAROVSKI ELEMENTS over the years, turning loose crystals into limitless creative possibilities. Designer Editions – Distinct Packaging <<< All products belonging to the assortment will be branded with the exclusive stamp “Designer Edition” directly on the packaging. -

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

Curlew River a PARABLE for CHURCH PERFORMANCE Op

The Yale School of Music, Robert Blocker, Dean and The Institute of Sacred Music, Margot Fassler, Dean present in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Music degree: The Yale Recital Chorus BENJAMIN BRITTEN Curlew River A PARABLE FOR CHURCH PERFORMANCE Op. 71 Libretto based on the medieval Japanese No-play Sumidagawa of Juro Motomasa (1395-1431) by WILLIAM PLOMER Christopher Hossfeld, conductor 5:00 pm 25 January 2004 Christ Church, New Haven 2 No production can go on without the help of many others and this one is no exception. I owe countless thanks and immeasurable gratitude to those who have made today’s recital possible: To my teachers, Maggi Brooks and Simon Carrington, for the guidance in exploring Curlew River and the tools to bring it to the ears of others. To my manager, Evan, for the legwork that brought everything together. To Robert Lehman and Christ Church, for allowing us to use this wonderful space. To my colleagues, Chuck, Holland, Rick, Kim, Joe, David, Michael, Evan, and Richard, for their time, musicality, advice, and expertise to learn this difficult music and make it happen. To my parents, Linda and Rod, my sister, Emily, my fiancé, Jimmy, and all the family and friends who made the journey to New Haven today, for their constant and enduring love and support. 3 PERFORMERS who make up the cast of the Parable: The Madwoman Charles Kamm, Tenor The Ferryman Holland Jancaitis, Baritone The Traveller Rick Hoffenberg, Baritone The Spirit of the Boy Kimberly Dunn, Soprano The Abbot Joseph Gregorio, Bass -

That to See How Britten Handles the Dramatic and Musical Materials In

BOOKS 131 that to see how Britten handles the dramatic and musical materials in the op- era is "to discover anew how from private pain the great artist can fashion some- thing that transcends his own individual experience and touches all humanity." Given the audience to which it is directed, the book succeeds superbly. Much of it is challenging and stimulating intellectually, while avoiding exces- sive weightiness, and at the same time, it is entertaining in the very best sense of the word. Its format being what it is, there are inevitable duplications of information, and I personally found the Garbutt and Garvie articles less com- pelling than the remainder of the book. The last two articles of Brett's, excel- lent as they are, also tend to be a little discursive, but these are minor reserva- tions. For anyone who cares for this masterwork of twentieth-century opera, Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/oq/article/4/3/131/1587210 by guest on 01 October 2021 or for Britten and his music, this book is obligatory reading. Carlisle Floyd Peter Grimes/Gloriana Benjamin Britten English National Opera/Royal Opera Guide 24 Nicholas John, series editor London: John Calder; New York: Riverrun Press, 1983 128 pages, $5.95 (paper) The English National Opera/Royal Opera Guides, small paperbacks with siz- able contents, are among the best introductions available to the thirty-plus operas published in the series so far. Each guide includes some essays by ac- knowledged authorities on various aspects of its subject, followed by a table of major musical themes, a complete libretto (original language plus transla- tion), a brief bibliography, and a discography. -

Popular Music, Stars and Stardom

POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM EDITED BY STEPHEN LOY, JULIE RICKWOOD AND SAMANTHA BENNETT Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN (print): 9781760462123 ISBN (online): 9781760462130 WorldCat (print): 1039732304 WorldCat (online): 1039731982 DOI: 10.22459/PMSS.06.2018 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design by Fiona Edge and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2018 ANU Press All chapters in this collection have been subjected to a double-blind peer-review process, as well as further reviewing at manuscript stage. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Contributors . ix 1 . Popular Music, Stars and Stardom: Definitions, Discourses, Interpretations . 1 Stephen Loy, Julie Rickwood and Samantha Bennett 2 . Interstellar Songwriting: What Propels a Song Beyond Escape Velocity? . 21 Clive Harrison 3 . A Good Black Music Story? Black American Stars in Australian Musical Entertainment Before ‘Jazz’ . 37 John Whiteoak 4 . ‘You’re Messin’ Up My Mind’: Why Judy Jacques Avoided the Path of the Pop Diva . 55 Robin Ryan 5 . Wendy Saddington: Beyond an ‘Underground Icon’ . 73 Julie Rickwood 6 . Unsung Heroes: Recreating the Ensemble Dynamic of Motown’s Funk Brothers . 95 Vincent Perry 7 . When Divas and Rock Stars Collide: Interpreting Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballé’s Barcelona . -

CB-1990-03-31.Pdf

TICKERTAPE EXECUTIVES GEFFEN’S NOT GOOFIN’: After Dixon. weeks of and speculation, OX THE rumors I MOVE I THINK LOVE YOU: Former MCA Inc. agreed to buy Geffen Partridge Family bassist/actor Walt Disney Records has announced two new appoint- Records for MCA stock valued at Danny Bonaduce was arrested ments as part of the restructuring of the company. Mark Jaffe Announcement about $545 million. for allegedly buying crack in has been named vice president of Disney Records and will of the deal followed Geffen’s Daytona Beach, Florida. The actor develop new music programs to build on the recent platinum decision not to renew its distribu- feared losing his job as a DJ for success of The Little Mermaid soundtrack. Judy Cross has tion contract with Time Warner WEGX-FM in Philadelphia, and been promoted to vice president of Disney Audio Entertain- Inc. It appeared that the British felt suicidal. He told the Philadel- ment, a new label developed to increase the visibilty of media conglomerate Thom EMI phia Inquirer that he called his Disney’s story and specialty audio products. Charisma Records has announced the appointment of Jerre Hall to was going to purchase the company girlfriend and jokingly told her “I’m the position of vice president, sales, based out of the company’s for a reported $700 million cash, going to blow my brains out, but New York headquarters. Hall joins Charisma from Virgin but David Geffen did not want to this is my favorite shirt.” Bonaduce Records in Chicago, where he was the Midwest regional sales engage in the adverse tax conse- also confessed “I feel like a manager.