A Case Study in Upper Gundar River Basin, Tamil Nadu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VIRUDHUNAGAR DISTRICT Minerals and Mining Irrigation Practices

VIRUDHUNAGAR DISTRICT Virudhunagar district has no access to sea as it is covered by land on all the sides. It is surrounded by Madurai on the north, by Sivaganga on the north-east, by Ramanathapuram on the east and by the districts of Tirunelveli and Tuticorin on the south. Virudhunagar District occupies an area of 4288 km² and has a population of 1,751,548 (as of 2001). The Head-Quarters of the district Virudhunagar is located at the latitude of 9N36 and 77E58 longitude. Contrary to the popular saying that 'Virudhunagar produces nothing, but controls everything', Virudhunagar does produce a variety of things ranging from edible oil to plastic-wares. Sivakasi known as 'Little Japan' for its bustling activities in the cracker industry is located in this district. Virudhunagar was a part of Tirunelveli district before 1910, after which it became a part of Ramanathapuram district. After being grafted out as a separate district during 1985, today it has eight taluks under its wings namely Aruppukkottai, Kariapatti, Rajapalayam, Sattur, Sivakasi, Srivilliputur, Tiruchuli and Virudhunagar. The fertility of the land is low in Virudhunagar district, so crops like cotton, pulses, oilseeds and millets are mainly grown in the district. It is rich in minerals like limestone, sand, clay, gypsum and granite. Tourists from various places come to visit Bhuminathaswamy Temple, Ramana Maharishi Ashram, Kamaraj's House, Andal, Vadabadrasayi koi, Shenbagathope Grizelled Squirrel Sanctuary, Pallimadam, Arul Migu Thirumeni Nadha Swamy Temple, Aruppukkottai Town, Tiruthangal, Vembakottai, Pilavakkal Dam, Ayyanar falls, Mariamman Koil situated in the district of Virudhunagar. Minerals and Mining The District consists of red loam, red clay loam, red sand, black clay and black loam in large areas with extents of black and sand cotton soil found in Sattur and Aruppukottai taluks. -

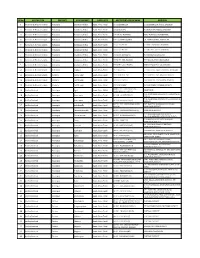

Sl.No. STATES/UTS DISTRICT SUB DISTRICT CATEGORY REPORTING UNITS NAME ADDRESS

Sl.No. STATES/UTS DISTRICT SUB DISTRICT CATEGORY REPORTING UNITS NAME ADDRESS 1 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Andamans Urban Stand Alone-Fixed ICTC BAMBOOFLAT CHC BAMBOOFLAT, SOUTH ANDAMAN 2 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Andamans Urban Stand Alone-Fixed ICTC BARATANG PHC BARATANG MIDDLE ANDAMAN 3 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Andamans Urban Stand Alone-Fixed ICTC DR. R.P HOSPITAL DR.R.P HOSPITAL, MAYABUNDER. 4 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Andamans Urban Stand Alone-Fixed ICTC G.B.PANT HOSPITAL G.B. PANT HOSPITAL, PORT BLAIR 5 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Andamans Urban Stand Alone-Fixed ICTC,CHC RANGAT CHC RANGAT,MIDDLE ANDAMAN 6 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Andamans Urban Stand Alone-Fixed ICTC,PHC HUT BAY PHC HUT BAY, LITTLE ANDAMAN 7 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Andamans Urban Stand Alone-Fixed ICTCS, PHC HAVELOCK PHC HAVELOCK, HAVELOCK 8 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Andamans Urban Stand Alone-Fixed ICTCS, PHC NEIL ISLANDS PHC NEIL ISLANDS, NEIL ISLANDS 9 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Andamans Urban Stand Alone-Fixed ICTCS,PHC GARACHARMA, DISTRICT HOSPITAL GARACHARMA 10 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Diglipur Stand Alone-Fixed ICTC DIGLIPUR CHC DIGLIPUR , NORTH & MIDDLE ANDAMAN 11 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Nicobars Car Nicobar Stand Alone-Fixed ICTC CAMPBELL BAY PHC CAMPBELL BAY, NICOBAR DISTRICT 12 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Nicobars Car Nicobar Stand Alone-Fixed ICTC CAR NICOBAR B.J.R HOSPITAL, CAR NICOBAR,NICOBAR 13 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Nicobars Car Nicobar Stand Alone-Fixed -

Annual W Ork Plan & BUDGET

SARVA SHIKSHA ABHIYAN DISTRICT ELEMENTARY EDUCATION PLAN annual w ork plan & BUDGET 2003-2004 MADURAI DISTRICT t a m il n a d u SARVA SHIKSHA ABHIYAN DISTRICT ELEMENTARY EDUCATION PLAN MADURAI DISTRICT ANNUAL WORK PLAN & BUDGET 2003 - 2004 Chapter I- Plan Overview Page 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Planning Process 2 1.3 General Profile 3 1.4 Educational Profile 5 1.4.1 Access 7 1.4.2 Enrolment - GER & NER 8 1.4.2.1 Boys 8& Girls 10 1.4.2.2 SC/ST Children 11 1.4.2.3 Disabled Children 12 1.4.3 Completion Rate 13 1.4.4 Attendance Rate 17 1.4.5 Transition Rate 18 1.4.6 Teacher Pupil Ratio 19 1.4.7 Achievement Level 20 1.5 Early Childhood Care and Education 21 1.6 Out of School Children 22 1.7 Special Focus Group 24 1.8 VECs, CRCs, BRCs 25 1.9 Infrastructure 26 1.9.1 Block Resource Centres 26 1.9.2 Cluster Resource Centres 27 1.9.3 Three Classrooms 27 1.9.4 Two Classrooms 27 1.9.5 Toilets 27 1.9.6 Drinking Water Facilities 28 1.10 District Project Office 28 iBKAHY 'laci##*! of -i;d f|:»inistr»ti©n,. 17-B. '»s Auv‘‘'-l”?aVj rrjiziE Se'^’ Chapter II - Progress Review P a g e 2.1 Introduction 29 2.2 Progress in ACCESS 29 2.2.1 Opening o f Primary Schools 30 2.2.2 Upper Primary Schools 31 2.2.3 EGS Centres 31 2.3 Progress in E N R O LM E N T 31 2.3.1 Boys & Girls 32 2.3.2 SC/ST 32 2.3.3 Disabled 33 2.4 Progress in C O M PLE T IO N 33 2.5 Retention 35 2.6. -

Scoping Exercise to Support Sustainable Urban Sanitation in Tamil Nadu SECONDARY REVIEW REPORT

Scoping Exercise to Support Sustainable Urban Sanitation in Tamil Nadu SECONDARY REVIEW REPORT Draft | December 2015 Document History and Status No. Issue Issued to Issued Review Approved Date Date by 1 Secondary Review Somnath Sen 30 Nov 3 Dec 2015 Kavita Report Draft 2015 Wankhade 2 Secondary Review Madhu 6 Dec 16 Dec 2015 Kavita Report Draft Krishna 2015 Wankhade (Revised) Printed 16 December 2015 Last Saved 16 December 2015 File Name TNSS Secondary Review Report Draft Project Lead Kavita Wankhade Project Director Somnath Sen Project Team Rajiv Raman, Devi Kalyani, Geetika Anand, Shivaram KNV, Chaya Ravishankar, Kavita Wankhade, Somnath Sen Name of Indian Institute for Human Settlements (IIHS) Organisation Name of Project Scoping Exercise to support Sustainable Urban Sanitation in Tamil Nadu Name of Client Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) Name of Document Scoping Exercise to support Sustainable Urban Sanitation in Tamil Nadu: Secondary Review Report Document Version Draft Project Number Practice/UES/2015/TNSS/2 Contract Number 31397 For Citation: IIHS, 2015. Scoping Exercise to support Sustainable Urban Sanitation in Tamil Nadu, Secondary Review Report – Draft Scoping Exercise to support Sustainable Urban Sanitation in TN: Secondary Review Report | December 2015 i Table of Contents Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................. iii Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ -

The Beneficiary Details of Custom Hiring Centres Established So Far with Subsidy Assistance of SMAM and NADP Scheme from the Year 2014-15 to 2020-21 Madurai

AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT The Beneficiary details of Custom Hiring Centres established so far with subsidy assistance of SMAM and NADP Scheme from the year 2014-15 to 2020-21 Madurai Sl. Name of Beneficiary Address of Custom Hiring Centre Name of Block Mobile No/Phone No. Name of Agrl.Machinery available in the centre Qty No. 1 Thiru.B.Kadal Kathiresan, Kadampatti, Karungalakudi (PO) Kottampatti MF 241 DI Mahasakthi Tractor - 1No. 1 S/O Balu Melur (TK) Madurai District MF 9000 Tractor - 1No. 1 TAFE Rotavator (36 Blades) - 1NO. 1 TAFE Rotavator (42 Blades)(1No) 1 MF 5245 DI Planetary drive Tractor - 1NO. 1 TAFE Rotavator (42 Blades) - 1NO. 1 VST Shakthi Powertiller - 2Nos. 2 Tractor drawn 9 tyne cultivator - 2Nos 2 Tractor drawn 9 tyne Rigid cultivator - 1No. 1 Battery operated Knapsack sprayer - 1No. 1 Aspee Power sprayer 1 Shakthiman post hole digger 1 Bheem pixel weeder - 1No. 1 2 Thiru.A.Subbaiah S/O Meenatchi thottam Melur 9442204550 New Holland 3630 Tractor - 1No. 1 Annamalai Kattayamapatti Melur (TK) Madurai New Holland 4710 Tractor - 1No. 1 Power weeder less than 20HP 1 9 tyne Spring cultivator - 1No. 1 9 Tyne Rigid cultivator - 1No. 1 Shakthiman Mobile shredder 1 Shakthiman Straw Baler -1No. 1 Shakthinan Rotavator SRT 6/1000 - 2Nos. 2 Shakthiman post hole digger - 1No. 1 Shakthiman Rotary Mulcher - 1No. 1 AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT The Beneficiary details of Custom Hiring Centres established so far with subsidy assistance of SMAM and NADP Scheme from the year 2014-15 to 2020-21 Madurai Sl. Name of Beneficiary Address of Custom Hiring Centre Name of Block Mobile No/Phone No. -

The Institute of Road Transport Driver Training Wing, Gummidipundi

THE INSTITUTE OF ROAD TRANSPORT DRIVER TRAINING WING, GUMMIDIPUNDI LIST OF TRAINEES COMPLETED THE HVDT COURSE Roll.No:17SKGU2210 Thiru.BARATH KUMAR E S/o. Thiru.ELANCHEZHIAN D 2/829, RAILWAY STATION ST PERUMAL NAICKEN PALAYAM 1 8903739190 GUMMIDIPUNDI MELPATTAMBAKKAM PO,PANRUTTI TK CUDDALORE DIST Pincode:607104 Roll.No:17SKGU3031 Thiru.BHARATH KUMAR P S/o. Thiru.PONNURENGAM 950 44TH BLOCK 2 SATHIYAMOORTHI NAGAR 9789826462 GUMMIDIPUNDI VYASARPADI CHENNAI Pincode:600039 Roll.No:17SKGU4002 Thiru.ANANDH B S/o. Thiru.BALASUBRAMANIAN K 2/157 NATESAN NAGAR 3 3RD STREET 9445516645 GUMMIDIPUNDI IYYPANTHANGAL CHENNAI Pincode:600056 Roll.No:17SKGU4004 Thiru.BHARATHI VELU C S/o. Thiru.CHELLAN 286 VELAPAKKAM VILLAGE 4 PERIYAPALAYAM PO 9789781793 GUMMIDIPUNDI UTHUKOTTAI TK THIRUVALLUR DIST Pincode:601102 Roll.No:17SKGU4006 Thiru.ILAMPARITHI P S/o. Thiru.PARTHIBAN A 133 BLA MURUGAN TEMPLE ST 5 ELAPAKKAM VILLAGE & POST 9952053996 GUMMIDIPUNDI MADURANDAGAM TK KANCHIPURAM DT Pincode:603201 Roll.No:17SKGU4008 Thiru.ANANTH P S/o. Thiru.PANNEER SELVAM S 10/191 CANAL BANK ROAD 6 KASTHURIBAI NAGAR 9940056339 GUMMIDIPUNDI ADYAR CHENNAI Pincode:600020 Roll.No:17SKGU4010 Thiru.VIJAYAKUMAR R S/o. Thiru.RAJENDIRAN TELUGU COLONY ROAD 7 DEENADAYALAN NAGAR 9790303527 GUMMIDIPUNDI KAVARAPETTAI THIRUVALLUR DIST Pincode:601206 Roll.No:17SKGU4011 Thiru.ULIS GRANT P S/o. Thiru.PANNEER G 68 THAYUMAN CHETTY STREET 8 PONNERI 9791745741 GUMMIDIPUNDI THIRUVALLUR THIRUVALLUR DIST Pincode:601204 Roll.No:17SKGU4012 Thiru.BALAMURUGAN S S/o. Thiru.SUNDARRAJAN N 23A,EGAMBARAPURAM ST 9 BIG KANCHEEPURAM 9698307081 GUMMIDIPUNDI KANCHEEPURAM DIST Pincode:631502 Roll.No:17SKGU4014 Thiru.SARANRAJ M S/o. Thiru.MUNUSAMY K 5 VOC STREET 10 DR. -

State Balanced Growth Fund

State Balanced Growth Fund Progress as on: 10/2020 District: ARIYALUR (Rupees in Lakh) Block Name S.No: Projec Project Name: Implementing SLEC: Date of AS: Project SBGF 1_Inst: 2_Inst: Total: Amount Actual % of Current State of the Project Due date of Expected Remarks t No.: Agency: Cost Cont.: Released to Expenditure Expn (Physical): Enter Component the Date of Implementin incurred by wise Details completion Completion g Agency: the of the of the Implementing Agency: Project: Project: State Balanced Growth Fund Jayankondam 1 1 Improving New JD Health III 22/01/2014 37.57 37.57 18.79 18.79 37.57 37.57 37.57 100 Work Completed, Documn. Completed born intensive care Service, Amount Fully utilized by Documn. Completed unit Perambalur Unspent Balance Remitted the IA Unspent Balance Remitted Un Spent 0.00 Amt. Remitted Balance 0.00 Available with IA UC Sent Dt of Completion 05/04/2018 Ariyalur 2 63 Equipments for GH-Ariyalur III 22/01/2014 2.53 2.53 2.53 0.00 2.53 2.53 2.52 100 Work Completed, Documn. Completed blood Bank balance Amount Rs 1000 Documn. Completed remitted to Govt Head Unspent Balance Remitted on 6.3.2019 Un Spent 0.01 Amt. Remitted Balance 0.00 Available with IA UC Sent Dt of Completion 03/11/2016 Ariyalur 3 189 Improved Surgical JD, Health IV 17/10/2014 10.35 10.35 10.35 0.00 10.35 10.35 10.35 100 Work Completed, Documn. Completed Care to the needy Service, Amount Fully Utilized by Documn. -

Home Tamilnadu Map Tirunelveli District Profile Print TIRUNELVELI

3/6/2017 Home TamilNadu Map Tirunelveli District Profile Print TIRUNELVELI DISTRICT PROFILE • Tirunelveli district is bounded by Virudhunagar district in the north, Thoothukudi district in the east, in the south by Gulf of Mannar and by Kerala State in the west and Kanniyakumari in the southwest. • The District lies between 08º08'09’’N to 09º24'30’’N Latitude, 77º08'30’’E to 77º58'30’’E Longitude and has an areal extent of 6810 sq.km. • There are 19 Blocks, 425 Villages and 2579 Habitations in the District. Physiography and Drainage: • Tirunelveli district falls in Tamiraparani river basin, which is the main river of the district. • The river has a large network of tributaries which includes the Peyar, Ullar, Karaiyar, Servalar, Pampar, Manimuthar, Varahanathi, Ramanathi, Jambunathi, Gadana nathi, Kallar, Karunaiyar, Pachaiyar, Chittar, Gundar, Aintharuviar, Hanumanathi, Karuppanathi and Aluthakanniar draining the district. • The river Tamiraparani originates from the hills in the west and enters Thoothukudi District and finally confluences in Bay of Bengal. • The other two rivers draining the district are river Nambiar and Hanumanathi of Nanguneri taluk in the south that are not part of the Tamiraparani river basin. • The small part of the district in the northern part falls in river Vaippar basin. Rainfall: The average annual rainfall and the 5 years rainfall collected from IMD, Chennai is as follows: Acutal Rainfall in mm Normal Rainfall in mm 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 896.90 724.00 918.20 1348.50 1546.80 845.10 Geology: Rock Type Geological -

District Survey Report for Clay (Others)

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT FOR CLAY (OTHERS) VIRUDHUNAGAR DISTRICT TAMILNADU STATE (Prepared as per Gazette Notification S.O.3611 (E) dated 25.07.2018 of Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climatic Change) 1 PREFACE In Compliance to the Notification Issued by the Ministry of Environment, ForestandClimatechangeDated15.01.2016,and its subsequent amended notification S.O.3611(E) dated 25.07.2018, the District Survey Report shall be prepared for each minor mineral in the district separately by the District Environment Impact Assessment Authority (DEIAA)with assistance of irrigation department, Drainage department, Forest department, Mining department and Revenue department in the district. Accordingly District Survey Report for the mineral Clay (Others) has been prepared as per the procedure prescribed in the notification S.O.3611(E) dated 25.07.2018 of Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. Every effort have been made to cover mining locations , areas & overview of Mining activity in the district with all its relevant features pertaining to geology & mineral wealth in replenishable and non- replenishable areas. This report will be a model and guiding document which is a compendium of available mineral resources, geographical setup, environmental and ecological setup of the District and is based on data of various departments, published reports and websites. 2 1.INTRODUCTION Virudhunagar District came into existence by the bifurcation of Ramanathapuram District vide State Government Notification, G.O. Ms. 347 dated 8.3.1985. It is bounded on North by Madurai and Sivagangai District, South by Tirunelveli and Tuticorin District, East by Ramanathapuram District, West by Kerala State and NorthWest by Theni District. -

Assessment of Available Sulphur Status in Major Green Gram Growing

International Journal of Chemical Studies 2019; 7(5): 4383-4389 P-ISSN: 2349–8528 E-ISSN: 2321–4902 IJCS 2019; 7(5): 4383-4389 Assessment of available sulphur status in major © 2019 IJCS Received: 19-07-2019 green gram growing blocks of Madurai Accepted: 21-08-2019 district of Tamil Nadu and creation of thematic B Jeevitha map using GIS Department of Soils and Environment, AC & RI, Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India B Jeevitha, A Rathinasamy, PP Mahendran and P Kannan A Rathinasamy Agricultural College & Research Abstract Institute, Eachangkottai, The study was conducted in major green gram growing blocks of Madurai district with a vision to assess Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, India the soil available sulphur status, since, sulphur plays a vital role in pulses crop production. Among PP Mahendran thirteen blocks of Madurai district, pulses were grown predominantly in five blocks viz., Thirumangalam, Department of Crop Usilampatti, T. Kallupatti, Sedapatti and Kalligudi according to their area, production and productivity. Management, Kudumiyanmalai, Two hundred and fifty soil samples were collected from green gram cultivating villages of those five Tamil Nadu, India major blocks. Overall soil available sulphur status in those five blocks ranged from 3.10 mg kg-1 to 18.20 mg kg-1 with a mean value of 10.65 mg kg-1. Overall soil samples results were categorized, in this 67 per P Kannan cent of soil samples found low in available sulphur status, 21 per cent of soil samples is medium status Department of Soils and and 12 per cent of soil samples under high status. Among the five blocks, Thirumangalam block soil Environment, AC & RI, samples has registered high percentage of low available sulphur status (84%) which is followed by Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India Usilampatti showed 82 percent low in available sulphur content. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2020 [Price : Rs.17.60 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No.3] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 15, 2020 Thai 1, Vikari, Thiruvalluvar Aandu – 2051 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages. Change of Names .. 63-105 Notices .. 105 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 892. I, V. Alamelu, wife of Thiru M. Saravanan, born on 895. I, R. Vellaisamy alias Vigneshwaran, son of Thiru 9th June 1980 (native district: Madurai), residing at No. 67, V Ravindran, born on 14th March 1989 (native district: Rajnagar 3rd Cross Street, Sammattipuram, Madurai-625 016, Madurai), residing at Old No. 11, New No. 165, Meenakshi Mill, shall henceforth be known as S. MURUGESWARI Old Colony, Andalpuram, Palanganatham Madurai-625 003, shall henceforth be known as R VIGNESHWARAN V. ALAMELU Madurai, 6th January 2020. R. VELLAISAMY alias VIGNESHWARAN Madurai, 6th January 2020. 893. I, M. Lilly, wife of (late) Thiru I. Murugan, born on 18th April 1940 (native district: Tirunelveli), residing at 896. My son, H. Anishwar, son of (late) Thiru K. Hari Sudhan, born on 8th February 2006 (native No. 293/216, Thillai Nagar, Sammattipuram, Madurai-625 016, district: Madurai), residing at No. 100B, Keela Perumal shall henceforth be known as M. -

Diocesan News Letter Madurai

Diocesan Pope’s General Intention for June 2013: Mutual respect : That a culture of dialogue, listening, and mutual respect may prevail News Letter among peoples. Pope’s Mission Intention for June 2013: New Evangelization : Madurai That where secularization is strongest, Christian communities may effectively promote a new evangelization. June 2013 (For Private Circulation Only) No. 602 PLEASE NOTE 1. Platinum Jubilee of the Archdiocese: With great joy and gratitude to God, we celebrate the Platinum Jubilee of the Archdiocese of Madurai on 7th July 2013. A solemn thanksgiving Eucharist will be celebrated by the Bishops of Tamilnadu at 5:30 p.m. at St. Britto School Ground, Gnanaolivupuram. All the parish priests are requested to bring the parishioners to this historical celebration in big numbers. Official information and invitation will follow as per protocol. By this all the religious both men and women and all the parishioners of the Archdiocese of Madurai are invited. Let us thank God for His guidance in the course of ecclesiastical history of this important Metropolitan See. - Msgr.. Z. Joseph Selvaraj, Fr. John Britto Packiaraj 2 The Souvenir Committee brings out on the Jubilee Day the follow- ing Books. 1. An edited Tamil book, "Palastheenam mudal Paandi Naadu varai", containing deep scientifc and throughly scholarly articles on the History of the Archdiocese of Madurai. It will be a scientific tool for all the ecclesiastical researchers to have access on the wider information on the said history. Kindly reserve your order for this book. 2. A well designed Platinum Jubilee Souvenir 3. A book in English on the Ecclesiastical history of the Archdio- cese of Madurai.