A Conspiracy of Sound: Modes of Listening in Brian De Palma’S Blow Out

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

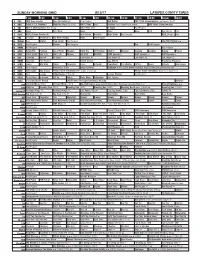

Sunday Morning Grid 8/13/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/13/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding 2017 PGA Championship Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Triathlon From Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. IAAF World Championships 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Invitation to Fox News Sunday News Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program The Pink Panther ›› 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program The Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central Liga MX (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana Juego Estrellas Gladiator ››› (2000, Drama Histórico) Russell Crowe, Joaquin Phoenix. -

BRICE DELLSPERGER Solitaires

**click here to access to the french version** BRICE DELLSPERGER Solitaires Exhibition from June 20 to July 30, 2020 43, rue de la Commune de Paris F-93230 Romainville For his new solo sow at Air de Paris, Brice Dellsperger presents two new films «Body Double 36» and «Body Double 37». «My Body Double videos are like doubles of movie sequences from the 70s or 80s: the title refers to Brian de Palma’s film (Body Double, 1984). To this day the series includes forty films with various running times, where the obsessive motif is the body of the double in mainstream movies. Following a rigorous but emancipating process, each selected scene is re-enacted by a single transvestite actor or actress, a super character who interprets all the parts by becoming double.» By appropriating the linear/ authoritarian form of a movie, the Body Double films aim at disrupting normative sexual genres through the means of a camp aesthetic.» Body Double 36 (2019) After Perfect (James Bridges, 1985) with Jean Biche. Aerobics were the fashion in the 80s! James Bridges’ Perfect was released in 1985. The film superficially describes human relationships in a gym club in Los Angeles, seen through the eyes of a journalist (John Travolta) who is beguiled by an androgynous gym coach (Jamie Lee Curtis). Studies on the postmodern body in contemporary American society are linked to the context of the 80s, a period which recognized an ideal body-object caught up by the AIDS epidemic. The identification of the HIV virus had a major influence on the perception and representation of bodies and sexuality. -

Broadcasting Taste: a History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media a Thesis in the Department of Co

Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media A Thesis In the Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada December 2016 © Zoë Constantinides, 2016 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Zoë Constantinides Entitled: Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Communication Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: __________________________________________ Beverly Best Chair __________________________________________ Peter Urquhart External Examiner __________________________________________ Haidee Wasson External to Program __________________________________________ Monika Kin Gagnon Examiner __________________________________________ William Buxton Examiner __________________________________________ Charles R. Acland Thesis Supervisor Approved by __________________________________________ Yasmin Jiwani Graduate Program Director __________________________________________ André Roy Dean of Faculty Abstract Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media Zoë Constantinides, -

Brice Dellsperger Body Double

Brice Dellsperger Body Double Curated by Selva Barni - Fantom Oct 24th — Nov 30th, 2018 Marsèlleria Via Paullo, 12/A Milan GROUND FLOOR 1. Body Double 10 Reprise of Brian de Palma's Obsession, 1997 1’ 27’’, loop With Dominique, Jean-luc Verna, Joy Falquet 2. Love/pursuit Body Double 3 Reprise of Brian de Palma's Body Double, 1995 1 1’50’’, loop With Brice Dellsperger Body Double 28 Reprise of Thomas Carter's Miami Vice Pilot (Brother's Keeper), 2013 2’46’’, loop With Brice Dellsperger 5 4 2 3. Despair 3 Body Double 21 Reprise of Roger Avary's The Rules of Attractions featuring V/VM's GROUND FLOOR sound design, 2005 19’56’’, loop With Lili Laxenaire, Joy Falquet, Sophie Lesné, Jean-Luc Verna, Carey Jeffries, William Carnimolla, Morgane Rousseau, Eva Carlton, Mercedes, Gwen Roch', Denis d'Arcangelo 4. Chases Body Double 4 Reprise of Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho as Donna Summer in Bad Girls, 1996 6’4’’, loop With Brice Dellsperger Body Double 5 Reprise of Brian de Palma's Dressed To Kill in Disneyland, 1996 5’40’’, loop With Brice Dellsperger Body Double 15 Reprise of Brian de Palma's Dressed to Kill, 2001 8’37’’, loop With Brice Dellsperger 5. Dead Star Body Double 26 Adaptation of Kenneth Anger's Hollywood Babylon I/II with Dead Can Dance's The Host Of Seraphim as a soundtrack, 2011 6’8’’, loop With Constance Legeay, Charleyne Boyer, Anita Gauran marselleria.org/body_double BASEMENT 6. Body Double 32 Reprise of Brian De Palma's Carrie, 2017 10’11’’ ca., loop 6 Music Didier Blasco With Alex Wetter BASEMENT FIRST FLOOR 7. -

The Talk of the Town Continues…

The Talk of the Town continues… “Kay Thompson was a human dynamo. My brothers and I were constantly swept up by her brilliance. Sam Irvin has captured all of this in his incredible book. I know you will thoroughly enjoy reading it.” – DON WILLIAMS, OF KAY THOMPSON & THE WILLIAMS BROTHERS “It’s an amazing book! Sam Irvin has captured Ms. T. to a T. I just re-read it and liked it even better the second time around.” – DICK WILLIAMS, OF KAY THOMPSON & THE WILLIAMS BROTHERS “To me, Kay was the Statue of Liberty. I couldn’t imagine how a book could do her justice but, by golly, Sam Irvin has done it. You won’t be able to put it down.” – BEA WAIN, OF KAY THOMPSON’S RHYTHM SINGERS “Kay was the hottest thing that ever hit the town and one of the most captivating women I’ve ever met in my life. There’ll never be another one like her, that’s for sure. A thorough examination of her astounding life was long overdue and I can’t imagine a better portrait than the one Sam Irvin has written. Heaven.” – JULIE WILSON “This fabulous Kay Thompson book totally captured her marvelous enthusiasm and talent and I’m delighted to be a part of it. I adore the cover with enchanting Eloise and the great picture of Kay in all her intense spirit!” – PATRICE MUNSEL “Thank you, Sam, for bringing Kay so richly and awesomely ‘back to life.’ Adventuring with Kay through your exciting book is like time-traveling through an incredible century of showbiz.” – EVELYN RUDIE, STAR OF PLAYHOUSE 90: ELOISE “At Metro… she scared the shit out of me! At Paramount… while shooting Funny Face… I got to know and love her. -

2Friday 1Thursday 3Saturday 4Sunday 5Monday 6Tuesday 7Wednesday 8Thursday 9Friday 10Saturday

JULY 2021 1THURSDAY 2FRIDAY DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME THEME: TCM BIRTHDAY TRIBUTE: WILLIAM WYLER KEEPING THE KIDS BUSY PRIMETIME THEME: PRIMETIME THEME: SELVIS FRIDAY NIGHT NEO-NOIR Seeing Double 8:00 PM Harper (‘66) 8:00 PM Kissin’ Cousins (‘64) 10:15 PM Point Blank (‘67) 10:00 PM Double Trouble (‘67) 12:00 AM Warning Shot (‘67) 12:00 AM Clambake (‘67) 2:00 AM Live A Little, Love a Little (‘68) 3SATURDAY 4SUNDAY DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME THEME: SATURDAY MATINEE HAPPY INDEPENDENCE DAY PRIMETIME THEME: PRIMETIME THEME: GABLE GOES WEST HAPPY INDEPENDENCE DAY 8:00 PM The Misfits (‘61) 8:00 PM Yankee Doodle Dandy (‘42) 10:15 PM The Tall Men (‘55) 10:15 PM 1776 (‘72) JULY JailhouseThes Stranger’s Rock(‘57) Return (‘33) S STAR OF THE MONTH: Elvis 5MONDAY 6TUESDAY 7WEDNESDAY P TCM SPOTLIGHT: Star Signs DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME AND PRIMETIME THEME(S): DAYTIME THEME: MEET CUTES DAYTIME THEME: TY HARDIN TCM PREMIERE PRIMETIME THEME: SOMETHING ON THE SIDE PRIMETIME THEME: DIRECTED BY BRIAN DE PALMA PRIMETIME THEME: THE GREAT AMERICAN MIDDLE TWITTER EVENTS 8:00 PM The Bonfire of the Vanities (‘90) PSTAR SIGNS Small Town Dramas NOT AVAILABLE IN CANADA 10:15 PM Obsession (‘76) Fire Signs 8:00 PM Peyton Place (‘57) 12:00 AM Sisters (‘72) 8:00 PM The Cincinnati Kid (‘65) 10:45 PM Picnic (‘55) 1:45 AM Blow Out (‘81) (Steeve McQueen – Aries) 12:45 AM East of Eden (‘55) 4:00 AM Body Double (‘84) 10:00 PM The Long Long Trailer (‘59) 3:00 AM Kings Row (‘42) (Lucille Ball – Leo) 5:15 AM Our Town (‘40) 12:00 AM The Bad and the Beautiful (‘52) (Kirk Douglas–Sagittarius) -

Production Designer Jack Fisk to Be the Focus of a Fifteen-Film ‘See It Big!’ Retrospective

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRODUCTION DESIGNER JACK FISK TO BE THE FOCUS OF A FIFTEEN-FILM ‘SEE IT BIG!’ RETROSPECTIVE Series will include Fisk’s collaborations with Terrence Malick, Brian De Palma, Paul Thomas Anderson, and more March 11–April 1, 2016 at Museum of the Moving Image Astoria, Queens, New York, March 1, 2016—Since the early 1970s, Jack Fisk has been a secret weapon for some of America’s most celebrated auteurs, having served as production designer (and earlier, as art director) on all of Terrence Malick’s films, and with memorable collaborations with David Lynch, Paul Thomas Anderson, and Brian De Palma. Nominated for a second Academy Award for The Revenant, and with the release of Malick’s new film Knight of Cups, Museum of the Moving Image will celebrate the artistry of Jack Fisk, master of the immersive 360-degree set, with a fifteen-film retrospective. The screening series See It Big! Jack Fisk runs March 11 through April 1, 2016, and includes all of Fisk’s films with the directors mentioned above: all of Malick’s features, Lynch’s Mulholland Drive and The Straight Story, De Palma’s Carrie and Phantom of the Paradise, and Anderson’s There Will Be Blood. The Museum will also show early B- movie fantasias Messiah of Evil and Darktown Strutters, Stanley Donen’s arch- affectionate retro musical Movie Movie, and Fisk’s directorial debut, Raggedy Man (starring Sissy Spacek, Fisk’s partner since they met on the set of Badlands in 1973). Most titles will be shown in 35mm. See below for schedule and descriptions. -

Understanding Steven Spielberg

Understanding Steven Spielberg Understanding Steven Spielberg By Beatriz Peña-Acuña Understanding Steven Spielberg Series: New Horizon By Beatriz Peña-Acuña This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Beatriz Peña-Acuña Cover image: Nerea Hernandez Martinez All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0818-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0818-7 This text is dedicated to Steven Spielberg, who has given me so much enjoyment and made me experience so many emotions, and because he makes me believe in human beings. I also dedicate this book to my ancestors from my mother’s side, who for centuries were able to move from Spain to Mexico and loved both countries in their hearts. This lesson remains for future generations. My father, of Spanish Sephardic origin, helped me so much, encouraging me in every intellectual pursuit. I hope that contemporary researchers share their knowledge and open their minds and hearts, valuing what other researchers do whatever their language or nation, as some academics have done for me. Love and wisdom have no language, nationality, or gender. CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One ................................................................................................. 3 Spielberg’s Personal Context and Executive Production Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 19 Spielberg’s Behaviour in the Process of Film Production 2.1. -

![Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3954/inmedia-3-2013-%C2%AB-cinema-and-marketing-%C2%BB-online-online-since-22-april-2013-connection-on-22-september-2020-603954.webp)

Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 3 | 2013 Cinema and Marketing Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.524 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference InMedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online since 22 April 2013, connection on 22 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ inmedia.524 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2020. © InMedia 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cinema and Marketing When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Cinema and Marketing: When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Nathalie Dupont and Joël Augros Jerry Pickman: “The Picture Worked.” Reminiscences of a Hollywood publicist Sheldon Hall “To prevent the present heat from dissipating”: Stanley Kubrick and the Marketing of Dr. Strangelove (1964) Peter Krämer Targeting American Women: Movie Marketing, Genre History, and the Hollywood Women- in-Danger Film Richard Nowell Marketing Films to the American Conservative Christians: The Case of The Chronicles of Narnia Nathalie Dupont “Paris . As You’ve Never Seen It Before!!!”: The Promotion of Hollywood Foreign Productions in the Postwar Era Daniel Steinhart The Multiple Facets of Enter the Dragon (Robert Clouse, 1973) Pierre-François Peirano Woody Allen’s French Marketing: Everyone Says Je l’aime, Or Do They? Frédérique Brisset Varia Images of the Protestants in Northern Ireland: A Cinematic Deficit or an Exclusive -

Professors Explore Foreign Policy, Election Tryouts Commence To

THE INDEPENDENT TO UNCOVER NEWSPAPER SERVING THE TRUTH NOTRE DAME AND AND REPORT SAINT Mary’s IT ACCURATELY V OLUME 50, ISSUE 127 | WEDNESDAY, APRIL 20, 2016 | NDSMCOBSERVER.COM P rofessors explore foreign policy, election ND Votes “Pizza, Pop and Politics” hosts discussion on foreign policy issues in the presidential election By LUCAS MASIN-MOYER issues, ” Desch said. N ews Writer Desch said this change in sentiment was largely due ND Votes hosted their final to “war weariness” and said installment of “Pizza, Pop, American voters are much and Politics” on Tuesday night more skeptical of involvement with Michael Desch, professor in foreign conflicts. of political science, and Mary “American voters are asking Ellen O’Connell, the Robert and the question, ‘What’s in it for Marion Short Professor of Law us?’ They want to be persuaded and research professor of in- that, if we go abroad in search ternational dispute resolution, of a monster, these are mon- speaking on issues of foreign sters that is in the interest of the policy related to the 2016 U.S. United States to slay,” he said. presidential election. Desch also touched upon the Desch began by speaking on seeming continuity between domestic public sentiment on candidates of the major parties United States foreign policy. on issues of foreign policy. “The message in 2014 and “Clinton and Cruz both be- 2015 is that there is a signifi- lieve that the United States GRACE TOURVILLE | The Observer cant uptick in the public’s pri- Michael Desch speaks Tuesday night in the Geddes Coffeehouse at the final “Pizza, Pop and Politics,” oritization of domestic political see POLICY PAGE 5 hosted by ND Votes. -

Rétrospective – Le Secret

Rétrospective – Le Secret Blow out, de Brian de Palma USA – 1981 – 1h47 - Couleur Fiche pédagogique rédigée par Sébastien Perreux Scénario : Brian de Palma Image : Vilmos Zsigmond Montage : Paul Hirsch Musique : Pino Donaggio Interprètes : John Travolta, Nancy Allen, John Lithgow Synopsis Jack est preneur de son dans le cinéma, et cherche un cri effroyable pour le film d’horreur sur lequel il travaille. Une nuit, alors qu’il capte des bruits dans la nature, il assiste à un accident de voiture dont il enregistre chaque détail sonore. Voyant que la voiture passe à travers la balustrade d’un pont et tombe à l’eau, il se jette au secours des passagers. Puis le lendemain, en écoutant l’enregistrement de l’accident de la veille, il se rend compte que le hasard n’y est sûrement pour rien. Avant la projection Biographie *Cinéaste américain né en 1940 d’origine italienne comme beaucoup d’autres grands réalisateurs de cette époque (Scorsese, Coppola…), même si ses origines n’auront pas autant d’importance dans son œuvre que pour ses contemporains. *C’est un adolescent plutôt doué, même plus, qui témoigne de vraies aptitudes pour les sciences et se lance dans l’invention de petites machines, encouragé en cela par des parents assez exigeants du point de vue de l’éducation. *A noter, trois chocs vécus dans sa jeunesse, tous essentiels dans la construction de sa personnalité : *Choc intime, personnel. Un épisode de sa jeunesse, moins anecdotique qu’il n’y paraît et dont on trouve des traces dans sa filmographie lorsque le jeune Brian découvrit sa mère inanimée, après qu’elle eut tenté de mettre fin à ses jours, du fait des infidélités à répétition du père.