THE GEOLOGY of the UNCONSOLIDATED SEDIMKTS of BOSTON HARBOR by DONALD PHIPPS -B.Sc., Mcgill University SUBMITTED in PARTIAL FULF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Harbor Watersheds Water Quality & Hydrologic Investigations

Boston Harbor Watersheds Water Quality & Hydrologic Investigations Fore River Watershed Mystic River Watershed Neponset River Watershed Weir River Watershed Project Number 2002-02/MWI June 30, 2003 Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Bureau of Resource Protection Boston Harbor Watersheds Water Quality & Hydrologic Investigations Project Number 2002-01/MWI June 30, 2003 Report Prepared by: Ian Cooke, Neponset River Watershed Association Libby Larson, Mystic River Watershed Association Carl Pawlowski, Fore River Watershed Association Wendy Roemer, Neponset River Watershed Association Samantha Woods, Weir River Watershed Association Report Prepared for: Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Bureau of Resource Protection Massachusetts Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Ellen Roy Herzfelder, Secretary Department of Environmental Protection Robert W. Golledge, Jr., Commissioner Bureau of Resource Protection Cynthia Giles, Assistant Commissioner Division of Municipal Services Steven J. McCurdy, Director Division of Watershed Management Glenn Haas, Director Boston Harbor Watersheds Water Quality & Hydrologic Investigations Project Number 2002-01/MWI July 2001 through June 2003 Report Prepared by: Ian Cooke, Neponset River Watershed Association Libby Larson, Mystic River Watershed Association Carl Pawlowski, Fore River Watershed Association Wendy Roemer, Neponset River Watershed Association Samantha Woods, Weir River Watershed -

Boston Harbor South Watersheds 2004 Assessment Report

Boston Harbor South Watersheds 2004 Assessment Report June 30, 2004 Prepared for: Massachusetts Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Prepared by: Neponset River Watershed Association University of Massachusetts, Urban Harbors Institute Boston Harbor Association Fore River Watershed Association Weir River Watershed Association Contents How rapidly is open space being lost?.......................................................35 Introduction ix What % of the shoreline is publicly accessible?........................................35 References for Boston Inner Harbor Watershed........................................37 Common Assessment for All Watersheds 1 Does bacterial pollution limit fishing or recreation? ...................................1 Neponset River Watershed 41 Does nutrient pollution pose a threat to aquatic life? ..................................1 Does bacterial pollution limit fishing or recreational use? ......................46 Do dissolved oxygen levels support aquatic life?........................................5 Does nutrient pollution pose a threat to aquatic life or other uses?...........48 Are there other water quality problems? ....................................................6 Do dissolved oxygen (DO) levels support aquatic life? ..........................51 Do water supply or wastewater management impact instream flows?........7 Are there other indicators that limit use of the watershed? .....................53 Roughly what percentage of the watersheds is impervious? .....................8 Do water supply, -

The Boston Harbor Project and the Reversal of Eutrophication of Boston Harbor

The Boston Harbor Project and the Reversal of Eutrophication of Boston Harbor Massachusetts Water Resources Authority Environmental Quality Department Report 2013-07 Citation: Taylor DI. 2013. The Boston Harbor Project and the Reversal of Eutrophication of Boston Harbor. Boston: Massachusetts Water Resources Authority. Report 2013-07. 33p. i THE BOSTON HARBOR PROJECT AND THE REVERSAL OF EUTROPHICATION OF BOSTON HARBOR Prepared by David I Taylor MASSACHUSETTS WATER RESOURCES AUTHORITY Environmental Quality Department and Department of Laboratory Services 100 First Avenue Charlestown Navy Yard Boston, MA 02129 (617) 242-6000 June 2013 Report No: 2013-01 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report draws on data collected by a number of monitoring projects. Grateful thanks are extended to the following Principal Investigators (PI) of these projects: Nancy Maciolek and James A. Blake AECOM Environment, Marine & Coastal Center, 89 Water Street, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA Anne E. Giblin and Jane Tucker The Ecosystems Center, Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA Robert J. Diaz Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary, Gloucester Pt., VA 23061, USA Charles T. Costello Division of Watershed Management, Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, 1 Winter Street, Boston MA 02108, USA Kelly Coughlin, Wendy Leo, Ken Keay, Laura Ducott ENQUAD, Massachusetts Water Resources Authority, 100 First Ave, Charlestown Navy Yard, MA 02129 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………. iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY………………………………………………………. 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………. 2 2.0 THE BOSTON HARBOR PROJECT (BHP) AND THE DECREASES IN INPUTS TO BOSTON HARBOR 2.1 Background on the BHP………………………………………… 3 2.2 Changes to the nutrient and organic matter inputs to the harbor…. -

Rainsford Island Shoreline Evolution Study (RISES) Christopher V

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Graduate Masters Theses Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses 12-2009 Rainsford Island Shoreline Evolution Study (RISES) Christopher V. Maio University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/masters_theses Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons, and the Oceanography Commons Recommended Citation Maio, Christopher V., "Rainsford Island Shoreline Evolution Study (RISES)" (2009). Graduate Masters Theses. Paper 86. This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RAINSFORD ISLAND SHORELINE EVOLUTION STUDY (RISES) A Thesis Presented by CHRISTOPHER V. MAIO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2009 Environmental, Earth, and Ocean Science Program © 2009 by Christopher V. Maio All rights reserved ABSTRACT RAINSFORD ISLAND SHORELINE EVOLUTION STUDY (RISES) December 2009 Christopher V. Maio, B.S. University of Massachusetts Boston M.S., University of Massachusetts Boston Directed by Assistant Professor Allen M. Gontz RISES conducted a shoreline change study in order to accurately map, quantify, and predict trends in shoreline evolution on Rainsford Island occurring from 1890-2008. It employed geographic information systems (GIS) and analytical statistical techniques to identify coastal hazard zones vulnerable to coastal erosion, rising sea-levels, and storm surges. The 11-acre Rainsford Island, located in Boston Harbor, Massachusetts, consists of two eroded drumlins connected by a low-lying spit. -

Boston Harbor National Park Service Sites Alternative Transportation Systems Evaluation Report

U.S. Department of Transportation Boston Harbor National Park Service Research and Special Programs Sites Alternative Transportation Administration Systems Evaluation Report Final Report Prepared for: National Park Service Boston, Massachusetts Northeast Region Prepared by: John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center Cambridge, Massachusetts in association with Cambridge Systematics, Inc. Norris and Norris Architects Childs Engineering EG&G June 2001 Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER 5b. GRANT NUMBER 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

Boston Harbor Watersheds

Boston Harbor Watersheds BOSTON HARBOR WATERSHED 6 Boston Harbor Watersheds Boston Harbor Watersheds Weir River Hingham Stream Length (mi) Stream Order pH Anadromous Species Present 4.9 Third 6.4 River herring, smelt, white perch, tomcod Obstruction # 1 Foundry Pond Dam Hingham River Type Material Spillway Spillway Impoundment Year Owner GPS Mile W (ft) H (ft) Acreage Built 2.7 Dam Concrete and 100 9.0 6.0 1998 Town of 42° 15’ 48.794” N stone Hingham 70° 51’ 38.082” W Foundry Pond Dam Fishway Present Design Material Length Inside Outside # of Baffle Notch Pool Condition/ (ft) W (ft) W (ft) Baffles H (ft) W (ft) L (ft) Function Notched Concrete 73.5 3.0 4.6 12 3.0 1.5 6.5 Good weir-pool Passable Fishway at Foundry Pond Dam 7 Boston Harbor Watersheds Remarks: Weir River forms a 6 acre impoundment as it flows to Boston Harbor. The 9 foot dam which creates the impoundment has recently been restored and the fishway that provides access was also modified at this time. Juvenile herring out-migration may be negatively impacted by the new rip-rap facing piled at the base of the dam. Efforts should be made to correct some of the detrimental impacts of the dam restoration. The area immediately downstream of the dam has historically supported a strong smelt population and white perch are known to spawn in the lower river. 8 Boston Harbor Watersheds Straits Pond Cohasset, Hull Stream Length (mi) Stream Order pH Anadromous Species Present 1.0 Second 8.9 River herring Obstruction # 1 Straits Pond Tidegate Cohasset, Hull River Type Material Spillway Spillway Impoundment Year Owner GPS Mile W (ft) H (ft) Acreage Built 1.0 Tide gate Metal 10.5 - 95.8 - Town of 42° 15’ 37.146” N Hull 70° 50’ 40.373” W Tidegate at Straits Pond Fishway None Remarks: This 95.8 acre salt pond is maintained at low salinities by a tide gate operated by the Town of Hull. -

(Osmerus Mordax) Spawning Habitat in the Weymouth- Fore River

Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Technical Report TR-5 Rainbow Smelt (Osmerus mordax) Spawning Habitat in the Weymouth- Fore River Bradford C. Chase and Abigail R. Childs Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Department of Fisheries, Wildlife and Environmental Law Enforcement Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Commonwealth of Massachusetts September 2001 Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Technical Report TR-5 Rainbow Smelt (Osmerus mordax) Spawning Habitat in the Weymouth-Fore River Bradford C. Chase and Abigail R. Childs Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Annisquam River Marine Fisheries Station 30 Emerson Ave. Gloucester, MA 01930 September 2001 Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Paul Diodati, Director Department of Fisheries, Wildlife and Environmental Law Enforcement Dave Peters, Commissioner Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Bob Durand, Secretary Commonwealth of Massachusetts Jane Swift, Governor ABSTRACT The spawning habitat of anadromous rainbow smelt in the Weymouth-Fore River, within the cities of Braintree and Weymouth, was monitored during 1988-1990 to document temporal, spatial and biological characteristics of the spawning run. Smelt deposited eggs primarily in the Monatiquot River, upstream of Route 53, over a stretch of river habitat that exceeded 900 m and included over 8,000 m2 of suitable spawning substrate. Minor amounts of egg deposition were found in Smelt Brook, primarily located below the Old Colony railroad embankment where a 6 ft culvert opens to an intertidal channel. The Smelt Brook spawning habitat is degraded by exposure to chronic stormwater inputs, periodic raw sewer discharges and modified stream hydrology. Overall, the entire Weymouth-Fore River system supports one of the larger smelt runs in Massachusetts Bay, with approximately 10,000 m2 of available spawning substrate. -

The Massachusetts Bay Hydrodynamic Model: 2005 Simulation

The Massachusetts Bay Hydrodynamic Model: 2005 Simulation Massachusetts Water Resources Authority Environmental Quality Department Report ENQUAD 2008-12 Jiang MS, Zhou M. 2008. The Massachusetts Bay Hydrodynamic Model: 2005 Simulation. Boston: Massachusetts Water Resources Authority. Report 2008-12. 58 pp. Massachusetts Water Resources Authority Boston, Massachusetts The Massachusetts Bay Hydrodynamic Model: 2005 Simulation Prepared by: Mingshun Jiang & Meng Zhou Department of Environmental, Earth and Ocean Sciences University of Massachusetts Boston 100 Morrissey Blvd Boston, MA 02125 July 2008 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Boston Harbor, Massachusetts Bay and Cape Cod Bay system (MBS) is a semi- enclosed coastal system connected to the Gulf of Maine (GOM) through boundary exchange. Both natural processes including climate change, seasonal variations and episodic events, and human activities including nutrient inputs and fisheries affect the physical and biogeochemical environment in the MBS. Monitoring and understanding of physical–biogeochemical processes in the MBS is important to resource management and environmental mitigation. Since 1992, the Massachusetts Water Resource Authority (MWRA) has been monitoring the MBS in one of the nation’s most comprehensive monitoring programs. Under a cooperative agreement between the MWRA and University of Massachusetts Boston (UMB), the UMB modeling team has conducted numerical simulations of the physical–biogeochemical conditions and processes in the MBS during 2000-2004. Under a new agreement between MWRA, Battelle and UMB, the UMB continues to conduct a numerical simulation for 2005, a year in which the MBS experienced an unprecedented red–tide event that cost tens of millions dollars to Massachusetts shellfish industry. This report presents the model validation and simulated physical environment in 2005. -

Terns Nesting in Boston Harbor: the Importance of Artificial Sites

Terns Nesting in Boston Harbor: The Importance of Artificial Sites Jeremy J. Hatch Terns are familiar coastal birds in Massachusetts, nesting widely, but they are most numerous from Plymouth southwards. Their numbers have fluctuated over the years, and the history of the four principal species was compiled by Nisbet (1973 and in press). Two of these have nested in Boston Harbor: the Common Tern (Sterna hirundo) and the Least Tern (S. albifrons). In the late nineteenth century, the numbers of all terns declined profoundly throughout the Northeast because of intensive shooting of adults for the millinery trade (Doughty 1975), reaching their nadir in the 1890s (Nisbet 1973). Subsequently, numbers rebounded and reached a peak in the 1930s, declined again to the mid-1970s, then increased into the 1990s under vigilant protection (Blodget and Livingston 1996). In contrast, the first terns to nest in Boston Harbor in the twentieth century were not reported until 1968, and there are no records from the 1930s, when the numbers peaked statewide. For much of their subsequent existence the Common Terns have depended upon a sequence of artificial sites. This unusual history is the subject of this article. For successful breeding, terns require both an abimdant food supply and nesting sites safe from predators. Islands in estuaries can be ideal in both respects, and it is likely that terns were numerous in Boston Harbor in early times. There is no direct evidence for — or against — this surmise, but one of the former islands now lying beneath Logan Airport was called Bird Island (Fig. 1) and, like others similarly named, may well have been the site of a tern colony in colonial times. -

BOHA Water Resources Scoping Report

BOSTON HARBOR ISLANDS – A NATIONAL PARK AREA, MASSACHUSETTS WATER RESOURCES SCOPING REPORT Mark D. Flora Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-2002/300 United States Department of the Interior • National Park Service The National Park Service Water Resources Division is responsible for providing water resources management policy and guidelines, planning, technical assistance, training, and operational support to units of the national park system. Program areas include water rights, water resources planning, regulatory guidance and review, hydrology, water quality, watershed management, watershed studies, and aquatic ecology. Technical Reports The National Park Service disseminates the results of biological, physical, and social research through the Natural Resources Technical Report Series. Natural resources inventories and monitoring activities, scientific literature reviews, bibliographies, and proceedings of technical workshops and conferences are also disseminated through this series. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the National Park Service. Copies of this report are available from the following: National Park Service (970) 225-3500 Water Resources Division 1201 Oak Ridge Drive, Suite 250 Fort Collins, CO 80525 National Park Service (303) 969-2130 Technical Information Center Denver Service Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225-0287 ii BOSTON HARBOR ISLANDS – A NATIONAL PARK AREA MASSACHUSETTS WATER RESOURCES SCOPING REPORT Mark D. Flora1 Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-2002/300 December, 2002 1Chief, Planning & Evaluation Branch, Water Resources Division, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Denver, Colorado This report was accepted and the recommendations endorsed by unanimous vote of the Boston Harbor Islands Partnership on December 17, 2002. -

Winthrop Boat Ramp to Lovells Island, Boston Harbor. 9:45Am – 2:30Pm

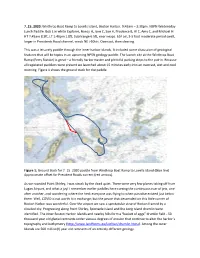

7_15_2020: Winthrop Boat Ramp to Lovells Island, Boston Harbor. 9:45am – 2:30pm. NSPN Wednesday Lunch Paddle. Bob L in white Explorer, Nancy H, Jane C, Sue H, Prudence B, Al C, Amy C, and Michael H. HT 7:45am 8.3ft, LT 1:46pm 1.8ft, tidal range 6.5ft, near neaps. 65F air, 3-5 foot moderate period swell, larger in Presidents Road channel, winds NE >10kts. Overcast, then clearing. This was a leisurely paddle through the inner harbor islands. It included some discussion of geological features that will be topics in an upcoming NPSN geology paddle. The launch site at the Winthrop Boat Ramp (Ferry Station) is great – a friendly harbormaster and plentiful parking steps to the put-in. Because all registered paddlers were present we launched about 15 minutes early into an overcast, wet and cool morning. Figure 1 shows the ground track for the paddle. Figure 1: Ground track for 7_15_2020 paddle from Winthrop Boat Ramp to Lovells Island (blue line) Approximate offset for President Roads current (red arrows). As we rounded Point Shirley, I was struck by the dead quiet. There were very few planes taking off from Logan Airport, and what a joy! I remember earlier paddles here cursing the continuous roar of jets, one after another, and wondering where the heck everyone was flying to when paradise existed just below them. Well, COVID is not worth it in exchange; but the peace that descended on this little corner of Boston Harbor was wonderful. Over the airport we saw a spectacular view of Boston framed by a clouded sky. -

Ocm17241103-1896.Pdf (5.445Mb)

rH*« »oo«i->t>fa •« A »iri or ok. w Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2011 witii funding from Boston Library Consortium IVIember Libraries littp://www.arcliive.org/details/annualreportofbo1896boar : PUBLIC DOCUMENT .... .... No. 11. ANNUAL REPORT Board of Harboe and Land Commissioners Foe the Yeab 1896. BOSTON WRIGHT & POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS, 18 Post Office Square. 1897. ,: ,: /\ I'l C0mm0ixixr^aIt{? of P^assar^s^tts* REPORT To the Honorable the Senate and House of Representatives of the Common- wealth of Massachusetts. The Board of Harbor and Land Commissioners, pursuant to the provisions of law, respectfully submits its annual re- port for the year 1896, covering a period of twelve months, from Nov. 30, 1895. Hearings. The Board has held one hundred and sixty-six formal ses- sions during the year, at which one hundred and eighty-three hearings were given. One hundred and twenty-one petitions were received for licenses to build and maintain structures, and for privileges in tide waters, great ponds and the Con- necticut River ; of these, one hundred and fifteen were granted, four withdrawn and two denied. On June 5, 1896, a hearing was given at Buzzards Bay on the petition of the town of Wareham that the boundary line on tide water between the towns of Wareham and Bourne at the highway bridge across Cohasset Narrows, as defined by the Board under chapter 196 of the Acts of 1881, be marked on said bridge. On June 20, 1896, a hearing was given in Nantucket on the petition of the local board of health for license to fill a dock.