Emily Kame Kngwarreye

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art Almanac April 2018 $6

Art Almanac April 2018 $6 Julie Dowling Waqt al-tagheer: Time of change Steve Carr Art Almanac April 2018 Subscribe We acknowledge and pay our respect to the many Aboriginal nations across this land, traditional custodians, Elders past and present; in particular the Established in 1974, we are Australia’s longest running monthly art guide and the single print Guringai people of the Eora Nation where Art Almanac destination for artists, galleries and audiences. has been produced. Art Almanac publishes 11 issues each year. Visit our website to sign-up for our free weekly eNewsletter. This issue spotlights the individual encounters and communal experience that To subscribe go to artalmanac.com.au contribute to Australia’s cultural identity. or mymagazines.com.au Julie Dowling paints the histories of her Badimaya ancestors to convey the personal impact of injustice, while a group show by art FROOHFWLYHHOHYHQíOWHUVWKHFRPSOH[LWLHVRI the Muslim Australian experience through diverse practices and perspectives. Links Deadline for May 2018 issue: between suburbia and nationhood are Tuesday 3 April, 2018. presented at Cement Fondu, and artist Celeste Chandler constructs self-portraits merging past and present lives, ultimately revealing the connectedness of human existence. Contact Editor – Chloe Mandryk [email protected] Assistant Editor – Elli Walsh [email protected] Deputy Editor – Kirsty Mulholland [email protected] Cover Art Director – Paul Saint National Advertising – Laraine Deer Julie Dowling, Black Madonna: Omega, -

Indigenous Australian Art in Intercultural Contact Zones

Coolabah, Vol.3, 2009, ISSN 1988-5946 Observatori: Centre d’Estudis Australians, Australian Studies Centre, Universitat de Barcelona Indigenous Australian art in intercultural contact zones Eleonore Wildburger Copyright ©2009 Eleanore Wildburger. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged Abstract: This article comments on Indigenous Australian art from an intercultural perspective. The painting Bush Tomato Dreaming (1998), by the Anmatyerre artist Lucy Ngwarai Kunoth serves as model case for my argument that art expresses existential social knowledge. In consequence, I will argue that social theory and art theory together provide tools for intercultural understanding and competence. Keywords: Indigenous Australian art and social theory. Introduction Indigenous Australian artworks sell well on national and international art markets. Artists like Emily Kngwarreye, Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, Kathleen Petyarre are renowned representatives of what has become an exquisite art movement with international appreciation. Indigenous art is currently the strongest sector of Australia's art industry, with around 6,000 artists producing art and craft works with an estimated value of more than A$300 million a year. (Senate Committee, 2007: 9-10) At a major Indigenous art auction held in Melbourne in 2000, Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula's famous painting Water Dreaming at Kalipinypa was sold for a record price of A$ 486,500. Three years before, it was auctioned for A$ 206,000. What did Johnny W. Tjupurrula receive? – just A$ 150 when he sold that painting in 1972. (The Courier Mail, 29 July 2000) The Süddeutsche Zeitung (06 September 2005) reports that Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri received A$ 100 for his painting Emu Corroboree Man in 1972. -

Sunday 24 March, 2013 at 2Pm Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, Australia Tional in Fi Le Only - Over Art Fi Le

Sunday 24 March, 2013 at 2pm Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, Australia tional in fi le only - over art fi le 5 Bonhams The Laverty Collection 6 7 Bonhams The Laverty Collection 1 2 Bonhams Sunday 24 March, 2013 at 2pm Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, Australia Bonhams Viewing Specialist Enquiries Viewing & Sale 76 Paddington Street London Mark Fraser, Chairman Day Enquiries Paddington NSW 2021 Bonhams +61 (0) 430 098 802 mob +61 (0) 2 8412 2222 +61 (0) 2 8412 2222 101 New Bond Street [email protected] +61 (0) 2 9475 4110 fax +61 (0) 2 9475 4110 fax Thursday 14 February 9am to 4.30pm [email protected] Friday 15 February 9am to 4.30pm Greer Adams, Specialist in Press Enquiries www.bonhams.com/sydney Monday 18 February 9am to 4.30pm Charge, Aboriginal Art Gabriella Coslovich Tuesday 19 February 9am to 4.30pm +61 (0) 414 873 597 mob +61 (0) 425 838 283 Sale Number 21162 [email protected] New York Online bidding will be available Catalogue cost $45 Bonhams Francesca Cavazzini, Specialist for the auction. For futher 580 Madison Avenue in Charge, Aboriginal Art information please visit: Postage Saturday 2 March 12pm to 5pm +61 (0) 416 022 822 mob www.bonhams.com Australia: $16 Sunday 3 March 12pm to 5pm [email protected] New Zealand: $43 Monday 4 March 10am to 5pm All bidders should make Asia/Middle East/USA: $53 Tuesday 5 March 10am to 5pm Tim Klingender, themselves aware of the Rest of World: $78 Wednesday 6 March 10am to 5pm Senior Consultant important information on the +61 (0) 413 202 434 mob following pages relating Illustrations Melbourne [email protected] to bidding, payment, collection fortyfive downstairs Front cover: Lot 21 (detail) and storage of any purchases. -

Breasts, Bodies, Art Central Desert Women's Paintings And

csr 12.1-02 (16-31) 3/8/06 5:36 PM Page 16 Central Desert Women’s Paintings and the breasts, bodies, art Politics of the Aesthetic Encounter JENNIFER L BIDDLE This paper is concerned with a culturally distinctive relationship between breasts and contemporary art from Central Desert Aboriginal women, specifically, recent works by Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Kathleen Petyarre and Dorothy Napangardi.1 Contra to the dominant interpretation of these paintings as representations of ‘country’—cartographic ‘maps’ of the landscape, narratives of Dreaming Ancestors, flora, fauna, species—my argument is that these works bespeak a particular breasted experience and expression, a cultural way of doing and being in the world; what I want to call a breasted ontology. I want to suggest that this breasted ontology is literally manifest in the ways in which these paintings are produced and, in turn, are experienced by the viewer. That is, these works arguably engender a bodily relation between viewer and image which is not about spectatorship. This viewing relation is not a matter of a viewing subject who, kept at a distance, comprehends an object of ocular focus and vision; rather, this relation instead is one in which the viewer relinquishes her sense of separateness from the canvas, where a certain coming- into-being in relation to the painting occurs. One does not so much know these works cognitively as lose oneself in them. Through viewing these works, as it were, one becomes vulnerable to their sensibilities in so far as they incite an enmeshment, an enfolding, and encapturing even in their materiality. -

Kathleen Petyarre

KATHLEEN PETYARRE Dates : c.1930 - 2018 Lieu de résidence : Atnangker, près d’Alice Springs en Australie Langues : Anmatyerre Support : batik sur soie, peinture acrylique sur toile Thèmes : Arnkerrth (Mountain Devil Lizard Dreaming), Green Pea Dreaming, Women Hunting Ankerr (emu), Arengk (Dingo Dreaming) EXPOSITIONS INDIVIDUELLES 2008 • Kathleen Petyarre - 2008, Metro 5 Gallery, Melbourne 2004 • Old Woman Lizard, Coo-ee Aboriginal Art, Sydney 2003 • Ilyenty - Mosquito Bore, Recent Paintings, Alcaston Gallery, Melbourne, Australie 2001 • Genius of Place: The work of Kathleen Petyarre, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australie • New Paintings by Kathleen Petyarre, Gallerie Australis & Coo-ee Gallery, at Mary Place Gallery, Paddington, Australie 2000 • Landscape: Truth and Beauty, Recent Paintings by Kathleen Petyarre, Alcaston Gallery 1999 • Recent Paintings by Kathleen Petyarre, Coo-ee Gallery, Mary Place, Sydney, Australie Biographie Kathleen Petyarre 19/12/18 1 / 10 ARTS D’AUSTRALIE • STEPHANE JACOB, PARIS 1998 • Arnkerrthe - My Dreaming, Alcaston Gallery, Melbourne, Australie 1996 • Kathleen Petyarre - Storm in Aknangkerre Country, Alcaston House Gallery, Melbourne, Australie EXPOSITIONS COLLECTIVES (SELECTION) 2015 • Parcours des Mondes, Arts d’Australie • Stéphane Jacob, Paris • Au cœur de l’art aborigène australien, Société Générale Private Banking/ Arts d’Australie • Stéphane Jacob, Monaco • Art Paris Art Fair, Arts d’Australie • Stéphane Jacob, Paris • VIBRATIONS : au cœur de l’art aborigène, Arts d’Australie • Stéphane Jacob -

Art Aborigène

ART ABORIGÈNE LUNDI 1ER JUIN 2009 AUSTRALIE Vente à l’Atelier Richelieu - Paris ART ABORIGÈNE Atelier Richelieu - 60, rue de Richelieu - 75002 Paris Vente le lundi 1er juin 2009 à 14h00 Commissaire-Priseur : Nathalie Mangeot GAÏA S.A.S. Maison de ventes aux enchères publiques 43, rue de Trévise - 75009 Paris Tél : 33 (0)1 44 83 85 00 - Fax : 33 (0)1 44 83 85 01 E-mail : [email protected] - www.gaiaauction.com Exposition publique à l’Atelier Richelieu le samedi 30 mai de 14 h à 19 h le dimanche 31 mai de 10 h à 19 h et le lundi 1er juin de 10 h à 12 h 60, rue de Richelieu - 75002 Paris Maison de ventes aux enchères Tous les lots sont visibles sur le site www.gaiaauction.com Expert : Marc Yvonnou 06 50 99 30 31 I GAÏAI 1er juin 2009 - 14hI 1 INDEX ABRÉVIATIONS utilisées pour les principaux musées australiens, océaniens, européens et américains : ANONYME 1, 2, 3 - AA&CC : Araluen Art & Cultural Centre (Alice Springs) BRITTEN, JACK 40 - AAM : Aboriginal Art Museum, (Utrecht, Pays Bas) CANN, CHURCHILL 39 - ACG : Auckland City art Gallery (Nouvelle Zélande) JAWALYI, HENRY WAMBINI 37, 41, 42 - AIATSIS : Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres JOOLAMA, PADDY CARLTON 46 Strait Islander Studies (Canberra) JOONGOORRA, HECTOR JANDANY 38 - AGNSW : Art Gallery of New South Wales (Sydney) JOONGOORRA, BILLY THOMAS 67 - AGSA : Art Gallery of South Australia (Canberra) KAREDADA, LILY 43 - AGWA : Art Gallery of Western Australia (Perth) KEMARRE, ABIE LOY 15 - BM : British Museum (Londres) LYNCH, J. 4 - CCG : Campbelltown City art Gallery, (Adelaïde) -

THE DEALER IS the DEVIL at News Aboriginal Art Directory. View Information About the DEALER IS the DEVIL

2014 » 02 » THE DEALER IS THE DEVIL Follow 4,786 followers The eye-catching cover for Adrian Newstead's book - the young dealer with Abie Jangala in Lajamanu Posted by Jeremy Eccles | 13.02.14 Author: Jeremy Eccles News source: Review Adrian Newstead is probably uniquely qualified to write a history of that contentious business, the market for Australian Aboriginal art. He may once have planned to be an agricultural scientist, but then he mutated into a craft shop owner, Aboriginal art and craft dealer, art auctioneer, writer, marketer, promoter and finally Indigenous art politician – his views sought frequently by the media. He's been around the scene since 1981 and says he held his first Tiwi craft exhibition at the gloriously named Coo-ee Emporium in 1982. He's met and argued with most of the players since then, having particularly strong relations with the Tiwi Islands, Lajamanu and one of the few inspiring Southern Aboriginal leaders, Guboo Ted Thomas from the Yuin lands south of Sydney. His heart is in the right place. And now he's found time over the past 7 years to write a 500 page tome with an alluring cover that introduces the writer as a young Indiana Jones blasting his way through deserts and forests to reach the Holy Grail of Indigenous culture as Warlpiri master Abie Jangala illuminates a canvas/story with his eloquent finger – just as the increasingly mythical Geoffrey Bardon (much to my surprise) is quoted as revealing, “Aboriginal art is derived more from touch than sight”, he's quoted as saying, “coming as it does from fingers making marks in the sand”. -

AUSTRALIA : CONTEMPORARY INDIGENOUS ART from the CENTRAL DESERT Kathleen PETYARRE, “My Country - Bush Seeds” Acrylic on Canvas, 137 X 137 Cm, 2010

AUSTRALIA : CONTEMPORARY INDIGENOUS ART FROM THE CENTRAL DESERT Kathleen PETYARRE, “My Country - Bush Seeds” acrylic on canvas, 137 x 137 cm, 2010 The paintings of Australian Indigenous artist Kathleen Petyarre have been compared internationally to those of the minimalist modern artists Mark Rothko and Agnes Martin, not so much for their formal structure: but for what underlies beneath, partially hidden from the observers view. In actuality, Kathelen Petyarre’s paintings are mental territorial maps which portray her country and the narrative associated with her inherited Dreaming stories. Her celebrated work, “My Country - Bush Seeds”, presents a seasonal snapshot within: a close-up of a geographical location spiritually important to the artist. The prominent parallel lines represent a group of red sand-hills – a sacred site - that rise majestically from the desert floor. Abie Loy KEMARRE, “Bush Hen Dreaming” acrylic on canvas, 91 x 152 cm, 2009 Australian Indigenous artist Abie Loy Kemarre began painting in 1994 under the formidable guidance of her famous grandmother, Kathleen Petyarre, who imparted the methodology for creating the depth-of-field of tiny shimmering dots in her highly delicate Bush Hen Dreaming painting that represents her Ancestral country. The Bush Hen travels through this country looking for bush seeds which are scattered over the land, represented by the fine dotting. The centre of this painting shows body designs used in traditionel women’s sacred ceremonies. These ceremonies are performed with songs and dance cycles telling stories of the Bush Hen Dreaming. Ngoia Pollard NAPALTJARRI, “Swamp around Nyruppi” acrylic on canvas, 180 x 180 cm, 2006 Western Desert artist Ngoia Pollard frequently paints particular Dreamings, or stories, for which she has personal responsibility or rights. -

Minnie Pwerle Cv

MINNIE PWERLE CV The extraordinarily powerful and prolific artist, Minnie Pwerle, was born in 1910 in Utopia; in bush country located about 350 kilometers North East of Alice Springs in the Northern Territory of Australia. She was to become, along with her contemporary, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, one of Australia's greatest female Aboriginal artists and upon her death in 2006, to be mourned by Aboriginal Art lovers all over the world. Minnie's Pwerle's paintings are now held in museums and exhibited in galleries worldwide, and they form an essential part of any serious Aboriginal Art collection. Born: Utopia SELECTED EXHIBITIONS: 2017 Sharing Country, Olsen Gruin Gallery, New York 2010 Minnie Pwerle and Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Kate Owen Gallery, Rozelle, NSW 2010 The Australian Indigenous Art Market Top 100 Exhibition, Coo-ee Aboriginal Art Gallery, Bondi, NSW 2010 Body Lines, Fireworks Gallery, Brisbane, QLD 2008 Emily and Her Legacy, Hillside Gallery in Tokyo, with Coo-ee Art Sydney in conjunction with the landmark retrospective exhibition 'Utopia - the Genius of Emily Kngwarreye' at the National Art Centre, Tokyo, Japan 2008 Atnwengerrp: Land of Dreaming, Minnie Pwerle carpet launch, Designer Rugs Showroom, Edgecliffe, NSW 2008 Colours of Utopia, Gallery Savah, Sydney NSW 2008 Utopia Revisited, NG Art Gallery, Chippendale, NSW 2007 New Works from Utopia, Space Gallery, Pittsburgh, PA, USA 2007 Group exhibition, APS Bendi Lango Art Exhibition with Rio Tinto, Fireworks Gallery, Brisbane, QLD 2007 Treasures of the Spirit, Tandanya Cultural Institute, Adelaide, SA 2007 Desert Diversity, group exhibition, Flinders Lane Gallery, Melbourne, VIC 2007 Group Exhibition, Australian Embassy, Washington, USA 2007 Utopia in New York, Robert Steele Gallery, New York. -

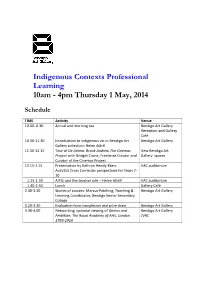

Bendigo Art Gallery Indigenous Contexts Professional Development

Indigenous Contexts Professional Learning 10am - 4pm Thursday 1 May, 2014 Schedule TIME Activity Venue 10.00- 0.30 Arrival and morning tea Bendigo Art Gallery Reception and Gallery Café 10.30-11.30 Introduction to indigenous art in Bendigo Art Bendigo Art Gallery Gallery collection: Helen Attrill 11.30-12.15 Tour of De Anima: Brook Andrew The Cinemas New Bendigo Art Project with Bridget Crone, Freelance Curator and Gallery spaces Curator of the Cinemas Project 12.15-1.15 Presentation by Kathryn Hendy-Ekers VAC auditorium AusVELS Cross Curricular perspectives for Years 7- 10 1.15-1.30 AITSL and the teacher role – Helen Attrill VAC auditorium 1.40-2.30 Lunch Gallery Café 2.30-3.20 Stories of success: Marcus Patching, Teaching & Bendigo Art Gallery Learning Coordinator, Bendigo Senior Secondary College 3.20-3.30 Evaluation form completion and prize draw Bendigo Art Gallery 3.30-4.00 Networking, optional viewing of Genius and Bendigo Art Gallery Ambition: The Royal Academy of Arts, London /VAC 1768-1918 Bendigo Art Gallery Indigenous Contexts Professional Learning Introduction The new rehang of Bendigo Art Gallery’s permanent collection after the completion of the multi-million dollar extension has provided an ideal opportunity to showcase the breadth of the gallery’s Australian artworks. Whilst it has been the first time in many years in which a chronological display has become possible, with rooms devoted to art from the 19th century, mid-20th century Modernism, 1990s and 21st century, the Howard Nathan Gallery (the first room) and the entrance to the gallery are currently dominated by paintings and sculptures by indigenous artists solely. -

Kathleen Petyarre

Kathleen Petyarre Kathleen Petyarre was born c. 1940, at the remote location of Atnangkere, an important water soakage for Aboriginal people on the western boundary of Utopia, 150 miles north-east of Alice Springs in the Northern Territory of Australia. Kathleen belongs to the Alyawarre / Eastern Anmatyerre clan and speaks Eastern Anmatyerre, with English as her second language. Kathleen, with her daughter Margaret and her sister's, settled at Mosquito Bore, on Utopia near her birthplace. Kathleen now spends part of the year at her residence in Adelaide. Kathleen's mother and seven sisters have managed to hold onto their land near Utopia as a group, establishing a camp at Atneftyeye Boundary Bore. Kathleen Petyarre married her “promised” husband, a much older man. From her late teens to her late twenties, Petyarre lived conform to what it meant to be a “traditional” Anmatyerr wife and mother. Separating from her husband, Petyarre was seeking another dimension to her life. For twenty years she worked as an assistant teacher at the Utopia School. This was the most significant and formative experience of her life, in terms of developing finely tuned intercultural negotiation and mediation skills. It was during this time, in the late 1970s, that Kathleen Petyarre became involved in Utopia batik. The context for his involvement was an astonishing renaissance of Indigenous artistic production. Collectively, the Utopia women began to make a name for themselves as batik artists, the most famous of whom is Kathleen’s late aunt, Emily Kame Kngwarreye. While she was involved in batik, Kathleen Petyarre became involved in a Land Claim of immense significance to the Anmatyerr. -

Indigenous People and Museums

Understanding Museums: Australian museums and museology Des Griffin and Leon Paroissien (eds) Indigenous people and museums Australian museums have had a leadership role in the wider recognition of the richness of Indigenous Australian culture and in addressing the history of contact between Indigenous Australians and those whose ancestral origins lay elsewhere. This section looks at ethnographic museums and collections, the intersections of culture and museological practice and the repatriation of Indigenous material. Contents Introduction, Des Griffin and Leon Paroissien Ethnographic museums and collections: from the past into the future, John E Stanton Transforming culture: Indigenous art and Australian art museums, Bernice Murphy Repatriation: the end of the beginning, Michael Pickering and Phil Gordon Online version: http://nma.gov.au/research/understanding- museums/Indigenous_people_and_museums.html Image credit: Budgerigars in the Sandhills, Billy Stockman Tjapaljarri, 1975. http://www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/papunya_painting/the_artists Understanding Museums - Indigenous people and museums 1 http://nma.gov.au/research/understanding-museums/Indigenous_people_and_museums.html National Museum of Australia Copyright and use © Copyright National Museum of Australia Copyright Material on this website is copyright and is intended for your general use and information. Your use of the material is subject to this copyright and use notice. The Museum does not own copyright in any of the authored content in Understanding Museums: Australian Museums and Museology. The authors own copyright and have licensed the Museum to publish the material. The Museum also does not own copyright in third-party images included in some of the chapters. Copyright owners are credited in the captions of the images. Use The material on this website is intended for personal, professional and educational use.