Management Principles and the Washington, DC Public Schools (A): Choosing a Chancellor Leigh Hafrey, Cate Reavis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thorn Pozen Confirmation Resolution of 2020”

COUNCIL OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE COMMITTEE REPORT 1350 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20004 DRAFT TO: All Councilmembers FROM: Chairman Phil Mendelson Committee of the Whole DATE: December 15, 2020 SUBJECT: Report on PR 23-1007, “Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority Board of Directors Thorn Pozen Confirmation Resolution of 2020” The Committee of the Whole, to which Proposed Resolution 23-1007, the “Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority Board of Directors Thorn Pozen Confirmation Resolution of 2020” was referred, reports favorably thereon, and recommends approval by the Council. CONTENTS I. Background And Need ...............................................................1 II. Legislative Chronology ..............................................................3 III. Position Of The Executive .........................................................4 IV. Comments Of Advisory Neighborhood Commissions ..............4 V. Summary Of Testimony .............................................................4 VI. Impact On Existing Law ............................................................4 VII. Fiscal Impact ..............................................................................5 VIII. Section-By-Section Analysis .....................................................5 IX. Committee Action ......................................................................5 X. Attachments ...............................................................................5 I. BACKGROUND AND NEED On November -

A Tale of Two Systems: Education Reform in Washington D.C

A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. BY DAVID OSBORNE A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. 2 PROGRESSIVE POLICY INSTITUTE A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. BY DAVID OSBORNE PROGRESSIVE POLICY INSTITUTE 3 A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS David Osborne would like to thank the Walton Family Foundation and the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation for their support of this work. He would also like to thank the dozens of people within D.C. Public Schools, D.C.’s charter schools, and the broader education reform community who shared their experience and wisdom with him. Thanks go also to those who generously took the time to read drafts and provide feedback. Finally, David is grateful to those at the Progressive Policy Institute who contributed to this report, including President Will Marshall, who provided editorial guidance, intern George Beatty, who assisted with research, and Steven K. Chlapecka, who shepherded the manuscript through to publication. 4 PROGRESSIVE POLICY INSTITUTE A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................. ii A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. HISTORY AND CONTEXT.............................................................. 1 MICHELLE RHEE BRINGS IN HER BROOM .................................................. 4 THE POLITICAL -

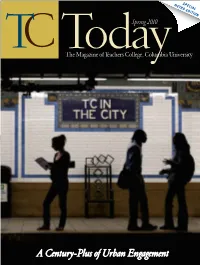

A Century-Plus of Urban Engagementt C T O D a Y L SPRING 2010 C 1 Spring 2010

SPECIAL METRO EDITION Spring 2010 TC TT The Magazineoo of Tdaeachersda College , Cyyolumbia University A Century-Plus of Urban EngagementT C T O D A Y l SPRING 2010 C 1 Spring 2010 ConteVnO LU M Ets 3 4 • N O . 2 FE at U R E S TC IN THE CITY: A HISTORY ScHOOLS AND COmmUNITIES Points of Contact 6 Rolling Up Our Sleeves 42 TC’s urban legacy is one of constant engagement to Partner with the Community Associate Vice President Nancy Streim discusses TEacHERS AND StUDENTS university-assisted schooling and TC’s efforts to strengthen the community it shares with its neighbors Teacher Observed—and Observing 9 Joining Forces 46 In TC’s Elementary Inclusive Education program, TC’s Partnership with 10 Harlem public schools “assessment” means knowing one’s students and oneself TC Builds a School 50 A Teaching Life 16 The College is at work on a new public pre-K—8 In her journey to understand “cultural literacies,” in West Harlem Ruth Vinz is an ongoing point of contact with city schools Faculty Partners 52 Teaching through Publishing 19 Seven TC professors are at the heart of the For Erick Gordon, director of TC’s Student Press Initiative, Harlem Partnership writing for publication is the curriculum Plus: Partners After School; TC’s Performing Arts Series; Listening to Lives from around the World 20 TC’s Zankel Fellows in the Partnership Schools Jondou Chen is leading an oral history project focused on immigrant students SOUND BODIES AND MINDS Been There, Still Doing That 21 Jacqueline Ancess takes the long view on education reform Fit to Learn 56 -

Former Navy SEAL Speaks of Humanitarian Efforts

carroll school of management spring 2012 winston UPDATE the winston center for leadership and ethics in this issue 1 former navy seal speaks of humanitarian efforts 2 jenks leadership program update, spring 2012 3 former dc mayor discusses urban education reform 4 pratt named o’connor family professor 6 around the table: lunch with a leader 6 research publications 7 rebecca skloot: the immortal life of henrietta lacks 7 winston forum on business ethics 8 recent table talk: lunch with a leader Former Navy SEAL Speaks of Humanitarian Efforts by samantha costanzo | as seen in the heights ric greitens is many things: a former navy seal, a photographer, would make this impossible for most of these E a Gold Glove boxer, a Rhodes scholar, an author, and a humanitarian. service members, there were still ways for them to serve their communities. Now, he can add Chambers Lecture Series speaker to that list. “It’s not a charity; it’s a challenge,” Greitens said of The Mission Continues, an organization Greitens spoke to a group of Boston College Though his naval career included tours in Iraq he and two friends started with their combat pay faculty and students, including ROTC members and Afghanistan, it is Greitens’ philanthropic and disability checks, respectively, in 2007. The and Carroll School of Management (CSOM) efforts that proved most inspiring to the Mission Continues matches former military students, in the Yawkey Center’s Murray audience. He talked about his experiences in members with what Greitens calls “service Function Room October -

National Press Club Luncheon with Washington, D.C

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON WITH WASHINGTON, D.C. MAYOR ADRIAN FENTY (D) SUBJECT: ISSUES AFFECTING THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA MODERATOR: JERRY ZREMSKI, PRESIDENT, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LOCATION: NATIONAL PRESS CLUB BALLROOM, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 1:00 P.M. EDT DATE: WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 3, 2007 (C) COPYRIGHT 2005, FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC., 1000 VERMONT AVE. NW; 5TH FLOOR; WASHINGTON, DC - 20005, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC. RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC. IS A PRIVATE FIRM AND IS NOT AFFILIATED WITH THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT. NO COPYRIGHT IS CLAIMED AS TO ANY PART OF THE ORIGINAL WORK PREPARED BY A UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT OFFICER OR EMPLOYEE AS PART OF THAT PERSON'S OFFICIAL DUTIES. FOR INFORMATION ON SUBSCRIBING TO FNS, PLEASE CALL JACK GRAEME AT 202-347-1400. ------------------------- MR. ZREMSKI: (Sounds gavel.) Good afternoon, and welcome to the National Press Club. My name is Jerry Zremski, and I'm the Washington Bureau Chief for the Buffalo News and president of the National Press Club. I'd like to welcome the Club members who are here today along with their guests and our audience watching on C-SPAN. We're looking forward to today's speech, and afterwords, I'll be asking as many questions as time permits. Please hold your applause during the speech so that we have as much time for questions as possible. -

A. Muriel Bowser B. Marion Barry C. Adrian Fenty D. Anthony Williams 2

1. Who is D.C.’s Mayor 4 Life? a. Muriel Bowser b. Marion Barry c. Adrian Fenty d. Anthony Williams 2. Where do you go at 3 in the morning? a. Stadium Nightclub b. D.C. Tunnel c. Pancake House d. Love Nightclub e. Statefarm 3. Which U.S. House of Representatives Delegate has served as a representative for the District of Columbia for over 20 years? a. Maxine Waters b. Condoleezza Rice c. Betsy Johnson d. Eleanor Holmes Norton 4. Who is the Godfather of Go-Go? a. James Funk b. Sugar Bear c. Chuck Brown d. Lil Benny 5. What is the original name of United Medical Center? a. Southeast Collaborative Hospital b. Community of Hope Hospital c. St. Elizabeths Hospital d. Greater Southeast Community Hospital 6. “Bitch set me up. I shouldn't have come up here . goddamn bitch.” Who said this? a. Marion Barry b. Chuck Brown c. Petey Greene d. Dave Chapelle 7. Which D.C. sports team did Michael Jordan play for? a. Washington Bullets b. Capital Bullets c. Washington Wizards d. Washington Nationals 8. What was the first black-owned bank in D.C.? a. Liberty Bank b. Industrial Saving Bank c. Andrews Federal Credit Union d. Bank on DC 9. Which of these famous attractions was originally located at Hains Point? a. Resurrecting Man b. The Awakening c. Zeus d. Sunken Man 10. When did Go-Go music originate? a. 1970s b. 1738 c. 1990s d. 1942 11. This pioneering black-owned streetwear brand was originally a beauty supply store on Georgia Ave that sold t-shirts. -

Human Relations Commission Investigating Anti-LGBT

OCTOBER 03 2014 VOLUME 45 ISSUE 40 • CELEBRATING 45 YEARS AS AMERICA’S GAY NEWS SOURCE • WASHINGTONBLADE.COM Holder leaves signifi cant LGBT rights legacy after stepping down as attorney general By CHRIS JOHNSON [email protected] After serving for more than six years as U.S. attorney general, Eric Holder leaves a signifi cant imprint on the record of the Obama administration — and at the forefront of that legacy is his role in advancing LGBT rights. At an event last week in the State Dining Room of the White House announcing his departure, President Obama said Holder made revitalizing the Civil Rights Division at the Justice Department a priority because he believes it’s “the conscience of the building.” “And several years ago, he recommended that our government stop defending the Defense of Marriage Act — a decision that was vindicated by the Supreme Court, and opened the door to federal recognition of same-sex marriage, and federal benefi ts for same-sex couples,” Obama said. “It’s a pretty good track record.” The sense that LGBT rights had signifi cantly advanced during the administration was echoed by Holder in remarks that followed Obama’s. “We have begun to realize the promise of equality for our LGBT brothers and sisters and their families,” Holder said. ‘We have begun to realize the promise of equality for our LGBT brothers and sisters and their CONTINUES ON PAGE 12 families,’ said ERIC HOLDER. Human relations commission into whether LGBT students at Cape Henlopen High discussion on the role that the State Human Relations investigating anti-LGBT discrimination School in the city of Lewes have been subjected to Commission can play in promoting amicable relations,” discrimination. -

Annual Report

2008 ANNUAL REPORT wamu.org | Your NPR news station in the Nation’s Capital A Letter from the General Manager Against a backdrop of an explosion of personalized media, it is increasingly challenging for a single radio station to serve disparate listener interests. In FY 2008, we stepped up to this challenge at WAMU 88.5 through several bold changes. These were designed to provide the high-quality content our listeners appreciate, while also satisfying increasing expectations for specialized services that allow listeners to select exactly what they want to hear, when they want to hear it. As a pioneer in the use of HD Radio technology, WAMU 88.5 has been well positioned from the beginning to harness its multicasting potential. In the fall of 2007, we felt it was time to begin treating HD Radio as “real” radio by maximizing the content we offer on the additional frequencies within our existing position at 88.5 on the radio dial. Thus, for the first time in our 46-year history, WAMU 88.5 switched to a seven-day week of news, talk, and information on our main channel, WAMU 88.5-1 in HD. This allowed us to move our Sunday bluegrass music programming from just one shelf of inventory in a large store to a brand new storefront of its own at WAMU 88.5-2. WAMU’s Bluegrass Country, with its own distinct, robust, live-hosted programs, is among the first in the nation to offer live programming exclusively for HD Radio. In creating this sustainable service, WAMU 88.5 increased by 59% Caryn G. -

Evans V. Fenty Submitted by CLARENCE J

Case: 1:76-cv-293 As of: 11/09/2017 02:46 PM EST 1 of 127 APPEAL,CLOSED,JURY,MEDIATION,REGISTRY U.S. District Court District of Columbia (Washington, DC) CIVIL DOCKET FOR CASE #: 1:76−cv−00293−ESH EVANS, et al v. FENTY, et al Date Filed: 02/23/1976 Assigned to: Judge Ellen S. Huvelle Date Terminated: 05/31/1995 Demand: $0 Jury Demand: Defendant Case in other court: USCA, 10−05109 Nature of Suit: 440 Civil Rights: Other Cause: 28:1331 Federal Question: Other Civil Rights Jurisdiction: Federal Question Special Master Margaret G. Farrell represented by Margaret G. Farrell Esquire 4719 Cumberland Avenue TERMINATED: 07/05/2011 Chevy Chase, MD 20815 (301) 654−8638 Email: [email protected] PRO SE Special Master Clarence J. Sundram represented by Clarence J. Sundram QUALITY MATTERS LLC 26 Abbey Road Delmar, NY 12054 (518) 527−1918 Fax: (240) 352−1434 Email: [email protected] PRO SE Special Master KATHY E. SAWYER 5532 Ash Grove Circle Montgomery, AL 36116 [email protected] Plaintiff JOY EVANS represented by Cathy E. Costanzo by and through her parents and next CENTER FOR PUBLIC friends, Betty Jane Evans and Harold G. REPRESENTATION Evans 22 Green Street Northampton, MA 01060 (413) 586−6024 Fax: (413) 586−5711 Email: ccostanzo@cpr−ma.org LEAD ATTORNEY ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Stephen F. Hanlon HOLLAND & KNIGHT, LLP 800 17th Street, NW Suite 1100 Washington, DC 20006 (202) 828−1871 Fax: (202) 955−5564 Email: [email protected] LEAD ATTORNEY ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Daniel Adlai Katz LAW OFFICES OF GARY M. -

Introduction 1

Notes Introduction 1. See, for example, Kip Lornell and Charles C. Stephenson, The Beat! Go-Go from Washington, D.C. (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2009), 2. 2. Howard Gillette, Jr., for instance, argues that national politics (namely, national urban policy) affected local urban planning, with both advantages and disadvan- tages for the city, including its prominent black population. Howard Gillette, Jr., Between Justice and Beauty: Race, Planning, and the Failure of Urban Policy in Washington, D.C. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), x–xi. We argue, however, that these three features of the city extend beyond urban policy to other spheres as well. 3. Alan Lessoff,The Nation and Its City: Politics, “Corruption,” and Progress in Wash- ington, D.C., 1861–1902 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994), 1; James H. S. McGregor, Washington: From the Ground Up (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), 297. 4. Carl Abbott perhaps puts it best when he writes that Washington has had both a vertical dimension (its national and international identity) and a horizontal dimension (its regional identity). Carl Abbott, Political Terrain: Washington, D.C., from Tidewater Town to Global Metropolis (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 6. 5. Mary Meade Coates, quoted in Jill Connors, ed., Growing Up in Washington, D.C.: An Oral History (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2001), 34. 6. Margaret Farrar, Building the Body Politic: Power and Urban Space in Washington, D.C. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008), 13. 7. Abbott 1999, 65–66, quotes pp. 7–8. 8. Our thanks to Tim Meagher for his conceptualization of Washington as a set of “cities.” 9. -

Index of /Sites/Default/Al Direct/2008/August

AL Direct, August 6, 2008 Contents U.S. & World News ALA News Booklist Online Division News Awards Seen Online Tech Talk Publishing The e-newsletter of the American Library Association | August 6, 2008 Actions & Answers Calendar U.S. & World News FBI seizes library computers; anthrax-case link suspected The FBI removed two public-access computers from the Frederick County Public Libraries’ C. Burr Artz Library in downtown Frederick, Maryland, July 30, anticipating their return within a week. The seizure is thought to be connected to the case of Army scientist Bruce E. Ivins (right), the late suspect in the 2001 anthrax letter attacks. Two FBI agents took the computers without presenting a court order, although the library’s normal procedure for such requests requires one.... American Libraries Online, Aug. 6; CBS-TV, Aug. 6 D.C. mayor finds funding to save libraries District of Columbia Mayor Adrian Fenty and Ginnie Cooper, chief librarian for D.C. Public Library, announced at an August 4 press conference that funding has been found to reverse $2 million in projected budget cuts that would have drastically cut library hours. “Residents can rest assured that they can continue to access all of D.C. Public Library’s resources seven days a week next year,” Fenty said, explaining that city officials The August issue of never intended to trigger cuts to library service.... Booklist features the American Libraries Online, Aug. 6; WRC-TV, Aug. 4 Fall Reference Preview. Sign up here to Oxford University halts VTLS implementation receive REaD Alert, a The University of Oxford and VTLS have ended their agreement to free e-newsletter implement the Virtua library management system. -

Occupant Protection • District Department of Transportation 8 • Metropolitan Police Department 12 • Associates for Renewed Education 14

DISTRICT DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION FISCAL YEAR 2006 ANNUAL HIGHWAY SAFETY REPORT ADRIAN FENTY MAYOR Prepared by the EMEKA MONEME Transportation Safety Division DIRECTOR Transportation Policy & Planning Administration Carole A. Lewis , Chief TABLE OF CONTENTS PLANNING & ADMINISTRATION 3 OCCUPANT PROTECTION • DISTRICT DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 8 • METROPOLITAN POLICE DEPARTMENT 12 • ASSOCIATES FOR RENEWED EDUCATION 14 BICYCLE SAFETY 17 ALCOHOL COUNTERMEASURES • WRAP 21 • METROPOLITAN POLICE DEPARTMENT-OVERVIEW 28 • ALCOHOL 31 • YOUTH & ALCOHOL 33 AGGRESSIVE DRIVING 36 POLICE TRAFFIC SERVICES 53 PEDESTRIAN SAFETY 55 • MASTER PLAN 57 • STREET SMART CAMPAIGN 58 ROADWAY SAFETY 71 ATTACHMENTS 74 2 PLANNING AND ADMINISTRATION DISTRICT DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION SECTION I: OVERVIEW INFORMATION The Highway Safety Office (Transportation Safety Division) is the focal point for highway safety issues in the District of Columbia. Along with the support of the Mayor’s Representative (Director, District Department of Transportation) the TSD provides leadership by developing, promoting, and coordinating programs; influencing public and private policy; and increasing public awareness of highway safety. Our partnerships include the Metropolitan Police Department, DC, Department of Motor Vehicles, Courts, the Attorney General’s Office, the University of the District of Columbia, hospitals, and private citizen organizations. The number of people killed in traffic crashes in the District of Columbia decreased by eight (8) in 2006. There were 49 traffic fatalities during 2005, up from 45 in 2004. The Planning and Administration program area includes those activities and costs necessary for the overall management and operations of the District of Columbia’s Highway Safety Office. The Chief of the Transportation Safety Division is responsible for the DC Highway Safety Program, and participates in activities that impact DDOT’s highway safety program and policies.