Assessing the Spatial Distribution Pattern of Street Greenery and Its Relationship with Socioeconomic Status and the Built Environment in Shanghai, China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shanghai Metro Map 7 3

January 2013 Shanghai Metro Map 7 3 Meilan Lake North Jiangyang Rd. 8 Tieli Rd. Luonan Xincun 1 Shiguang Rd. 6 11 Youyi Rd. Panguang Rd. 10 Nenjiang Rd. Fujin Rd. North Jiading Baoyang Rd. Gangcheng Rd. Liuhang Xinjiangwancheng West Youyi Rd. Xiangyin Rd. North Waigaoqiao West Jiading Shuichan Rd. Free Trade Zone Gucun Park East Yingao Rd. Bao’an Highway Huangxing Park Songbin Rd. Baiyin Rd. Hangjin Rd. Shanghai University Sanmen Rd. Anting East Changji Rd. Gongfu Xincun Zhanghuabang Jiading Middle Yanji Rd. Xincheng Jiangwan Stadium South Waigaoqiao 11 Nanchen Rd. Hulan Rd. Songfa Rd. Free Trade Zone Shanghai Shanghai Huangxing Rd. Automobile City Circuit Malu South Changjiang Rd. Wujiaochang Shangda Rd. Tonghe Xincun Zhouhai Rd. Nanxiang West Yingao Rd. Guoquan Rd. Jiangpu Rd. Changzhong Rd. Gongkang Rd. Taopu Xincun Jiangwan Town Wuzhou Avenue Penpu Xincun Tongji University Anshan Xincun Dachang Town Wuwei Rd. Dabaishu Dongjing Rd. Wenshui Rd. Siping Rd. Qilianshan Rd. Xingzhi Rd. Chifeng Rd. Shanghai Quyang Rd. Jufeng Rd. Liziyuan Dahuasan Rd. Circus World North Xizang Rd. Shanghai West Yanchang Rd. Youdian Xincun Railway Station Hongkou Xincun Rd. Football Wulian Rd. North Zhongxing Rd. Stadium Zhenru Zhongshan Rd. Langao Rd. Dongbaoxing Rd. Boxing Rd. Shanghai Linping Rd. Fengqiao Rd. Zhenping Rd. Zhongtan Rd. Railway Stn. Caoyang Rd. Hailun Rd. 4 Jinqiao Rd. Baoshan Rd. Changshou Rd. North Dalian Rd. Sichuan Rd. Hanzhong Rd. Yunshan Rd. Jinyun Rd. West Jinshajiang Rd. Fengzhuang Zhenbei Rd. Jinshajiang Rd. Longde Rd. Qufu Rd. Yangshupu Rd. Tiantong Rd. Deping Rd. 13 Changping Rd. Xinzha Rd. Pudong Beixinjing Jiangsu Rd. West Nanjing Rd. -

Shanghai, China: Jinqiao and Zhangjiang Industrial Park Area Hotel Market

Singapore: Hotel Market Market Report - March 2019 MARKET REPORT Shanghai, China: Jinqiao and Zhangjiang Industrial Park Area Hotel Market MARCH 2020 Shanghai, China: Jinqiao and Zhangjiang Hotel Market Market Report - March 2020 Introduction The planned area of Zhangjiang is 79.7 square kilometers. Shanghai Jinqiao Export Processing Zone (hereinafter In April 2015, Zhangjiang’s 37.2 square kilometers planned “Jinqiao”) is located at Pudong New District, Shanghai. area was officially incorporated into the China (Shanghai) Jinqiao used to be a state-level economic and technological Pilot Free Trade Zone. Currently, Zhangjiang has two major development zone established at the beginning of Pudong industrial clusters: the “medical industry” cluster focusing New District’s development in 1990, with a planned area on pharmaceutical related industries and the “Internet of 27.38 square kilometers. industry” cluster focusing on Internet and mobile Internet related industries. However, in December 2014, Jinqiao’s 20.48 square kilometers planned area was officially incorporated into After almost 30 years of development, especially after the China (Shanghai) Pilot Free Trade Zone. Jinqiao is joining the Free Trade Zone, Jinqiao and Zhangjiang have a traditional manufacturing industry base with many developed into a world-renowned export processing research and development headquarters of manufacturing zone and a high-technology park. Their infrastructure and enterprises. industrial development have also become more mature. There are four major industries in Jinqiao, namely Considering Jinqiao and Zhangjiang are both important to automotive and parts industry, modern home appliance the Pudong Free Trade Zone Areas, we have selected the industry, biomedicine and food industry as well as following upper-midscale to upper-upscale hotels to review electronic information industry. -

First Long-Term and Near Real-Time Measurement of Trace Elements in China’S Urban Atmosphere: Temporal Variability, Source Apportionment and Precipitation Effect

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 11793–11812, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-11793-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. First long-term and near real-time measurement of trace elements in China’s urban atmosphere: temporal variability, source apportionment and precipitation effect Yunhua Chang1,2,3, Kan Huang4, Mingjie Xie5, Congrui Deng4, Zhong Zou4,6, Shoudong Liu1,2,3, and Yanlin Zhang1,2,3 1Yale-NUIST Center on Atmospheric Environment, International Joint Laboratory on Climate and Environment Change (ILCEC), Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, Nanjing 210044, China 2Key Laboratory of Meteorological Disaster, Ministry of Education (KLME)/ Collaborative Innovation Center on Forecast and Evaluation of Meteorological Disasters (CIC-FEMD), Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, Nanjing 210044, China 3Jiangsu Provincial Key Laboratory of Agricultural Meteorology, College of Applied Meteorology, Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, Nanjing 210044, China 4Center for Atmospheric Chemistry Study, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Atmospheric Particle Pollution and Prevention (LAP3), Department of Environmental Science and Engineering, Fudan University, Shanghai 200433, China 5School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, Nanjing 210044, China 6Pudong New Area Environmental Monitoring Station, Shanghai 200135, China Correspondence: Yanlin Zhang ([email protected], [email protected]) -

OACAC Regional Institute, Shanghai August 17-‐18, 2015 -‐-‐ Attendee List

OACAC Regional Institute, Shanghai August 17-18, 2015 -- Attendee list (as of Aug 10) First Name Last Name Institution Institution Location Sherrie Huan The University of Sydney Australia Rhett Miller University of Sydney Australia Alexander Bari MODUL University Vienna Austria Sven Clarke The University of British Columbia Canada Leanne Stillman University of Guelph Canada David Zutautas University of Toronto Canada Matthew Abbate Dulwich ColleGe ShanGhai China Katherine Arnold ShanGhai Qibao DwiGht HiGh School China LihenG Bai Shenzhen Cuiyuan Middle School China Michelle Barini ShanGhai American School-PudonG China David Barrutia Beijing No. 4 HiGh School China John Beck Due West Education ConsultinG Company Limited China Christina Chandler EducationUSA China Barbara Chen Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth China DonGsonG Chen ZhenGzhou Middle School China Jane Chen TsinGhua University HiGh School China Marilyn Cheng Bridge International Education China Jennifer Cheong Suzhou SinGapore International School China Chorku Cheung Yew ChunG International School China Jeffrey Cho Shenzhen Middle School China Gloria Chyou InitialView China Alice Cokeng ShenyanG No.2 Sino-Canadian HiGh School China Valery Cooper YK Pao School China Ted Corbould ShanGhai United International School China Terry Crawford InitialView China Sabrina Dubik KinGlee HiGh School China Kelly Flanagan Yew ChunG International School ShanGhai Century Park China Candace Gadomski KinGlee HiGh School China Lucien Giordano Dulwich ColleGe Suzhou China Hamilton GreGG HGIEC -

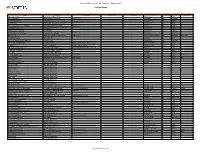

Creditor Matrix

Case 19-10488 Doc 15 Filed 03/11/19 Page 1 of 103 Creditor Matrix NAME ADDRESS 1 ADDRESS 2 ADDRESS 3 ADDRESS 4 CITY STATE ZIP COUNTRY 1 MILLION 4 ANNA 15301 DALLAS PKWY #1100 ADDISON TX 75001 119 LEAWOOD LLC TOWN CENTER CROSSING PO BOX 3536 COLUMBUS OH 43260-3536 1515 N HALSTED LLC PO BOX 851319 MINNEAPOLIS MN 55485-1319 1515 N HALSTED, LLC C/O BUCKSBAUM RETAIL PROPERTIES 71 S WACKER DR, STE 2310 CHICAGO IL 60606 22 INTERIORS 3940 LAUREL CANYON BLVD. #1022 STUDIO CITY CA 91604 223-1 DL HOLDINGS LLC-LA92800 C/O INWOOD NATIONAL BANK PO BOX 9124 DALLAS TX 75209 23RD GROUP LLC 4994 PARKWAY PLAZA BLVD. STE 400 CHARLOTTE NC 28217 24 SEVEN STAFFING INC. PO BOX 5786 HICKSVILLE NY 11802-5786 3 GGG'S TRUCK LINES INC. PO BOX 4003 SOUTH GATE CA 90280 3 GGG'S TRUCK LINES INC. C/O NATIONAL BANKERS TRUST PO BOX 1752 MEMPHIS TN 38101-1752 360 CATERING AND EVENTS LLC. 5439 PERSHING AVENUE FORT WORTH TX 76107 3BS CO. LTD. 64/282 ROYALNINE BUILDING 25 FL RAMA 9 RD BANGKAPI HUAYKWANG TH BANGKOK THAILAND 3S CORPORATION 1251 E WALNUT CARSON CA 90746 4 LEATHER REPAIR 2785 WEIGL ROAD SAGINAW MI 48609 4698 CLAY TERRACE PARTNERS LLC PO BOX 643726 PITTSBURGH PA 15264-3726 4TH STREET HOLDINGS LLC C/O BOND RETAIL 5 THIRD STREET, STE 1225 SAN FRANCISCO CA 94103 770 TAMALPAIS DRIVE INC. C/O MADISON MARQUETTE-MGMT OFFICE 100 CORTE MADERA TOWN CENTER CORTE MADERA CA 94925 80 TWENTY LLC ATTN: ALP ONURLU 657 MISSION ST., STE 402 SAN FRANCISCO CA 94105 A&G REALTY PARTNERS, LLC ATTN: ANDREW GRAISER 445 BROADHOLLOW ROAD, SUITE 410 MELVILLE NY 11747 A&S HOME FASHION CORP. -

Filename Description Category Duration Apartment Rooftop Shanghai AMB B-Format.Wav Quiet Rooftop, Shanghai, China, Ambisonics, D

Filename Description Category Duration Apartment_Roo,op_Shanghai_AMB_B-format.wav Quiet Roo,op, Shanghai, China, Ambisonics, Downtown, ResidenBal Neighborhood Ambience - Urban 04:39.6 Century_Park_01_Shanghai_AMB_B-format.wav Century Park, Shanghai, China, Ambisonics, Quiet, Birds, Distance Traffic, Occasional Walla Ambience - Urban 03:19.2 Century_Park_02_Shanghai_AMB_B-format.wav Century Park, Shanghai, China, Ambisonics, Quiet, Birds, Distance Traffic, Crowd, Group Walla Ambience - Urban 05:10.5 Downtown_Fuzhou_Road_IntersecBon_Shanghai_AMB_B-format.wav Downtown Shanghai, Fuzhou Road IntersecBon, China, Ambisonics, Pedestrians, Footsteps, Sidewalk, Traffic, Bicycles, Car and Truck Pass Bys, Walla Ambience - Urban 07:39.8 Downtown_Resident_Area_Shanghai_AMB_B-format.wav Downtown Shanghai, China, Ambisonics, ResidenBal, AcBve Crowd ConversaBon, Birds, Distant Traffic, Group Walla Ambience - Urban 06:39.7 Huangpu_River_Ferry_Deck_01_Shanghai_AMB_B-format.wav Huangpu River Ferry, Deck, Shanghai, China, Ambisonics, P.A. Announcement, So, Engine Rumble, Water, Walla Ambience - NauBcal 08:13.7 Huangpu_River_Ferry_Deck_02_Shanghai_AMB_B-format.wav Huangpu River Ferry, Deck, Shanghai, China, Ambisonics, P.A. Announcement, So, Engine Rumble, Water, Distant Bow Wash, Walla Ambience - NauBcal 06:48.7 Huangpu_Riverside_Waitan_PerspecBve_01_Shanghai_AMB_B-format.wav Huangpu River, Waterside Promenade, Shanghai, China, Ambisonics, Park, Distant Traffic, Group Walla, Bell Ring Ambience - Urban 03:42.8 Huangpu_Riverside_Waitan_PerspecBve_02_Shanghai_AMB_B-format.wav -

Remote Sensing of Urbanization and Environmental Impacts

Remote Sensing of Urbanization and Environmental Impacts Jan Haas Doctoral Thesis in Geoinformatics February 2016 TRITA-SOM 2016-01 ISSN 1654-2754 ISNR KTH/SoM/2016-01/SE ISBN 978-91-7595-852-1 Jan Haas Doctoral Thesis Division of Geoinformatics Department of Urban Planning and Environment Royal Institute of Technology (KTH) SE-10044 Stockholm, Sweden ii Abstract It is a well-known fact that current population forecasts and trends predict a continuous increase in world population in the upcoming decades. This leads to increased demands for natural resources and living space. As a consequence, urban areas have been growing considerably and new settlements and urban agglomerations keep emerging on a global scale. Data and methods to observe and quantify the changes of and induced through urban growth are thus needed to address the challenges of present and future urbanization trends. This thesis research focuses on the establishment of analytical frameworks for the detection of urban growth patterns based on spaceborne remote sensing data at multiple scales, spatial and temporal resolutions and on the evaluation of environmental impacts through the well-established concepts of landscape metrics and ecosystem services, their extension and combination. Urbanization does not progress uniformly but shows large spatial and temporal disparities. The unprecedented and often unstructured growth of urban areas is nowadays most apparent in Africa and Asia. China in particular has undergone rapid urbanization already since the late 1970s. The need for new residential, commercial and industrial areas leads to new urban regions challenging sustainable development and the maintenance and creation of a high living standard as well as the preservation of ecological functionality. -

Hotel Reservation Form Deadline: February 10, 2021

Hotel Reservation Form Form Deadline: February 10, 2021 March 17-19, 2021 Shanghai China 11 Please return form to: Exhibitor Name: _______________________________ Shanghai Vision Expo & Meeting Solutions Co., Ltd. _____________________Booth Number: ___________ Phone: +86.21.5481.6051 Address: _____________________________________ +86.21.5481.6052 Fax: +86.21.5481.6032 Contact Person: _______________________________ Contact Person: Phone: _______________Fax: ___________________ Ms. Jenny Zhang / Mr. Paul Hou E-mail: Email: _______________________________________ [email protected]; Mobile: ______________________________________ [email protected] Please read the hotel information and notice carefully when fill in this reservation form. * is compulsory fields. *Title: □ Mr. □ Ms. □ Mrs. Others____________________ *Company Name: Surname: ______________________________________ *Guest Name: First Name: ______________________________________ □ Kerry Hotel Pudong Shanghai ☆☆☆☆☆ □ Jumeirah Himalayas Hotel ☆☆☆☆☆ □ Grand Mercure Shanghai Century Park ☆☆☆☆☆ *Official Hotel: □ Holiday Inn Shanghai Pudong ☆☆☆☆ □ Holiday Inn Shanghai JinXiu ☆☆☆☆ □ Ibis Hotel (Shanghai Expo Dongming Road) ☆☆☆ *Room Type: □ Single □ Twin *Daily Room Rate (RMB): *Breakfast: □ One □ Two *Arrival Date: *Departure Date: Special Requirements: □ No Hotel Limo Airport Pickup Service: □ Yes. Arrival Flight / Time:________________________________ *Type of Credit Card: □ Visa □ Master □Amex □ JCB Others _______________ *Credit Card Number: *Expiry Date: Signature: -

World Bank Document

E541 Environmental Assessment for Shanghai Urban Environment Project Environmental Assessment Public Disclosure Authorized for Shanghai Urban Environment Project (Draft) Table of Contents I INTRODUCTION ............................................. 4 Public Disclosure Authorized 1.1 BACKGROUND ............................................. - 4.4 1.2 LEGISLATIVE AND REGULATORY CONSIDERATIONS .............................................. 5 2 PROPOSED APL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME .............................................. 6 2.1 OVERALL STRUCTURE OF THE STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK ............................................. 6 2.2 PRELIMINARY PHASING ARRANGEMENT OF THE PROPOSED APL PROGRAMME ......................................... 7 2.2.1 Phase One ........................................................................... 7 2.2.2 Phase Two ............................................................................ 9 2.2.3 Phase Three ............................................................................. 12 2.3 SUMMARY OF THE PROPOSED APL PROJECT ................................................... ........................... 13 3 ASSESSMENT OF THE PROPOSED APL STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK ........................................ 15 Public Disclosure Authorized 3.1 ANALYSIS OF COMPATIBILITY OF APL STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK WITH SHANGHAI MASTER PLAN .......... 15 3.2 COMPATIBILITY WITH COMPREHENSIVE REDEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME ALONG MVERSIDES OF THE HUANGPU RIVER .............................................................................. 17 3.2.1 Briefing -

BEIJING -The Forbiden City BEIJING -The Great Wall BEIJING -Heaven Temple/ Summer Palace Designed by Herzog & De Meuron

BEIJING -The forbiden city BEIJING -The great wall BEIJING -Heaven temple/ summer palace Designed by Herzog & de Meuron BEIJING -Birds Nest National Stadium Designed by PTW Architects BEIJING -Watercube National Swim- ming Centre Designed by Paul Andreu BEIJING -National Grand Theater of China Designed by OMA BEIJING -CCTV TV Station HQ Designed by gmp Architekten BEIJING -National Museum of China Designed by Steven Holl BEIJING -Linked Hybrid Designed by Studio Pei-Zhu, Urbanus Architecture & Desig BEIJING -Digital Beijing Designed by MAD BEIJING -le cheng kindergarten Designed by daipu architects BEIJING -force field hutong Designed by tanzospace design office BEIJING -cultural space of no. 16 ban- gchiao for a century, the bund has been one of the most recognizable symbols and the pride of Shanghai. The architecture along the Bund is a living museum of the colonial history of the 1800s. You’ve never been to Shanghai if you haven’t seen the Bund. The Bund is a famous waterfront and regarded as the symbol of Shanghai for hundreds of years. It is on the west bank of Huangpu River from the Waibaidu Bridge to Nanpu Bridge and winds 1500 meters in length. The most famous and attractive sight which is at the west side of the Bund are the 26 various buildings of different architectural styles including Gothic, Baroque, Romanesque, Classicism and the Renaissance. The 1,700 meters long flood-control wall, known as ‘the lovers’ wall’, located on the side of Huangpu River from Huangpu Park to Xinkai River and once was the most romantic corner in Shanghai in the last century. -

Download Shanghai Subway

7 1 3 Tieli Rd. Baoyang Rd. 10 8 6 Fujin Rd. Shanghai Metro Map North Jiading Meilan Lake Shiguang Rd. Gangcheng Rd. North Youyi Rd. Xinjiangwancheng Updated May 2011 Luonan Xincun West Youyi Rd. Jiangyang Rd. North Waigaoqiao West Jiading Shuichan Rd. Nenjiang Rd. Free Trade Zone Bao’an Highway East Yingao Rd. To check ticket prices, find the fastest route, 11 Gucun Park Songbin Rd. Baiyin Road Xiangyin Rd. Hangjin Rd. East check train times, hear station names in Shanghai Gongfu Xincun Zhanghuabang Sanmen Rd. Anting Changji Road Jiading University Huangxing Park Mandarin, and more, visit exploreshanghai.com Xincheng South Waigaoqiao Hulan Rd. Songfa Rd. Free Trade Zone Shanghai Shanghai Nanchen Rd. Jiangwan Stadium Malu Automobile City Circuit South Changjiang Rd. Middle Yanji Rd. Tonghe Xincun Xinzhuang – Fujin Road Shangda Rd. Wujiaochang Zhouhai Rd. 1 Nanxiang West Yingao Rd. Huangxing Rd. Gongkang Rd. Changzhong Rd . Guoquan Rd. Taopu Xincun Jiangwan Town Wuzhou Avenue 2 East Xujing – Pudong International Airport Jiangpu Rd. Penpu Xincun Dachang Town Wuwei Rd. Dabaishu Tongji University Dongjing Rd. 3 Shanghai South Railway Station – North Jiangyang Road Wenshui Rd. Anshan Xincun Qilianshan Rd. Xingzhi Rd. Chifeng Rd. Shanghai Quyang Rd. Siping Rd. Jufeng Rd. Liziyuan Circus World 4 Loop line Dahuasan Rd. North Xizang Rd. Hongkou Shanghai West Football Youdian Xincun Yanchang Rd. Stadium Railway Station Xincun Rd. Wulian Rd. Xinzhuang – Minhang Development Zone North Zhongxing Rd. 5 2 Zhenru Zhongshan Rd. Langao Rd. Dongbaoxing Rd. Boxing Rd. Shanghai Linping Rd. Fengqiao Rd. 6 Gangcheng Road – Oriental Sports Center East Xujing Zhongtan Rd. Railway Station Caoyang Rd. -

SCIS Pudong Schools & Housing Guide

Dongjing Rd. S. 1. SCIS PD US 198 Hengqiao Road 17. Pinnacle Century Park 99 Dongxiu Road PUDONG SCHOOLS & HOUSING GUIDE 2. SCIS PD LS 800 Xiuyan Road 18. Xiangmei Garden 1650 Jinxiu Road Jufeng Rd. S. 3. Emerald 2888 Huamu Road 19. Golden Vienna 333 Jinxiu Road Metro Line 6 4. Tiziano 1 Xiuyan Road 20. Green Court 777 Biyun Road Wulian Rd. S. 5. Bellewood 491 Huanlin Dong Road 21. Green Villas 700 Biyun Road 6. Trinity 1168 Xiuyan Road 22. Green Hills 418 Jinxiu Dong Road Boxing Rd. S. 7. Oasis Villas 1801 Kangqiao Road 23. Shimao Lakeside 188 Mingyue Road Luoshan Road Jingqiao Rd. S. 8. Shimao Riviera 1 Weifang Xi Road 24. Vizcaya 2000 Yunshan Road Lanson Place 9. Yanlord Garden 99 Pucheng Road 25. San Marino Bridge 199 Tang’an Road Yunshan Rd. S. Outer Ring Highway 10. Thomson Garden 666 Longdong Avenue 26. Palm Spring Villas 3800 Longdong Avenue Deping Rd. S. 11. Tomson Riviera 28 Huayuanshiqiao Road 27. Poly Jinjue 75 Xinxi Road Pudong Ave. S. 20. Green Court 12. Thomson Golf Villa 1 Longdong Avenue 28. Shanghai Links 1600 Lingbai Road Beiyang Jing Rd. S. Oriental Pearl Pines Market Radio and TV Tower 21. Green Villas 13. Regency Park 1983 Huamu Road 29. Dong Hai Yu Ting 5888 Huaxia Dong Road Lujiazui. S. Metro Line 4 Minsheng Rd. S. 20. Green Court 21. Green Villas 14. Yanlord Town 1599 Dingxiang Road 30. Opal Villa 328 Lanxue Road 23. Shimao Lakeside 24. Vizcaya 15. Dongjiao Garden 1800 Jinke Road 31. Peninsula Villa 688 Jianghuan Road Yuanshen Yanggao Middle Road Stadium.