Sample Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Socio-Cultural Investigation of Indigenous Fijian Women's

A Socio-cultural Investigation of Indigenous Fijian Women’s Perception of and Responses to HIV and AIDS from the Two Selected Tribes in Rural Fiji Tabalesi na Dakua,Ukuwale na Salato Ms Litiana N. Tuilaselase Kuridrani MBA; PG Dip Social Policy Admin; PG Dip HRM; Post Basic Public Health; BA Management/Sociology (double major); FRNOB A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2013 School of Population Health Abstract This thesis reports the findings of the first in-depth qualitative research on the socio-cultural perceptions of and responses to HIV and AIDS from the two selected tribes in rural Fiji. The study is guided by an ethnographic framework with grounded theory approach. Data was obtained using methods of Key Informants Interviews (KII), Focus Group Discussions (FGD), participant observations and documentary analysis of scripts, brochures, curriculum, magazines, newspapers articles obtained from a broad range of Fijian sources. The study findings confirmed that the Indigenous Fijian women population are aware of and concerned about HIV and AIDS. Specifically, control over their lives and decision-making is shaped by changes of vanua (land and its people), lotu (church), and matanitu (state or government) structures. This increases their vulnerabilities. Informants identified HIV and AIDS with a loss of control over the traditional way of life, over family ties, over oneself and loss of control over risks and vulnerability factors. The understanding of HIV and AIDS is situated in the cultural context as indigenous in its origin and required a traditional approach to management and healing. -

METHODIST PIONEERS in the SOUTH PACIFIC by Rev

METHODIST PIONEERS IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC By Rev. Dr F. Baker The first chaplain appointed to New South Wales in 1786 was a Methodist in the secondary sense of being a devout evangelical clergyman, and was deliberately sponsored as such by William Wilberforce, friend and admirer of the Wesleys. The second who arrived under Wilberforce's auspices, Samuel Marsden (1765-1838),1 was similar in spirituality, but much tougher both in spirit and in body. His Methodism was even nearer to that of Wesley, for he had been born into a Yorkshire Wesleyan family. and apparently became one of their lay preachers.2 He was educated for the Anglican ministry at the expense of the Elland Clerical Society, an evangelical group founded in 1767 by Wesley's friend the Rev. Henry Venn, vicar of Huddersfield.3 By them he was sent to Hull Grammar School (aged 23!) and then on to Magdalene College. Cambridge, where he was befriended by Rev. Charles Simeon, after whom he named one of his children.4 The dire straits of the Chaplain in New South Wales, however, undoubtedly stressed by Governor Phillip in person as well as by Johnson himself in letters, made Wilberforce and his friends extremely anxious to secure another evangelical candidate as quickly as possible. Therefore they exerted pressure on Marsden, even to the extent of persuading him to leave Cambridge without graduating. His agreement was a measure of his Christian dedication, and also proof that they had indeed chosen the right man, eminently qualified by spiritual gifts, by robust strength, and by practical training. -

The Case for Lau and Namosi Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali

ACCOUNTABILITY IN FIJI’S PROVINCIAL COUNCILS AND COMPANIES: THE CASE FOR LAU AND NAMOSI MASILINA TUILOA ROTUIVAQALI ACCOUNTABILITY IN FIJI’S PROVINCIAL COUNCILS AND COMPANIES: THE CASE FOR LAU AND NAMOSI by Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Commerce Copyright © 2012 by Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali School of Accounting & Finance Faculty of Business & Economics The University of the South Pacific September, 2012 DECLARATION Statement by Author I, Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali, declare that this thesis is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published, or substantially overlapping with material submitted for the award of any other degree at any institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text. Signature………………………………. Date……………………………… Name: Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali Student ID No: S00001259 Statement by Supervisor The research in this thesis was performed under my supervision and to my knowledge is the sole work of Mrs. Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali. Signature……………………………… Date………………………………... Name: Michael Millin White Designation: Professor in Accounting DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my beloved daughters Adi Filomena Rotuisolia, Adi Fulori Rotuisolia and Adi Losalini Rotuisolia and to my niece and nephew, Masilina Tehila Tuiloa and Malakai Ebenezer Tuiloa. I hope this thesis will instill in them the desire to continue pursuing their education. As Nelson Mandela once said and I quote “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The completion of this thesis owes so much from the support of several people and organisations. -

We Are Kai Tonga”

5. “We are Kai Tonga” The islands of Moala, Totoya and Matuku, collectively known as the Yasayasa Moala, lie between 100 and 130 kilometres south-east of Viti Levu and approximately the same distance south-west of Lakeba. While, during the nineteenth century, the three islands owed some allegiance to Bau, there existed also several family connections with Lakeba. The most prominent of the few practising Christians there was Donumailulu, or Donu who, after lotuing while living on Lakeba, brought the faith to Moala when he returned there in 1852.1 Because of his conversion, Donu was soon forced to leave the island’s principal village, Navucunimasi, now known as Naroi. He took refuge in the village of Vunuku where, with the aid of a Tongan teacher, he introduced Christianity.2 Donu’s home island and its two nearest neighbours were to be the scene of Ma`afu’s first military adventures, ostensibly undertaken in the cause of the lotu. Richard Lyth, still working on Lakeba, paid a pastoral visit to the Yasayasa Moala in October 1852. Despite the precarious state of Christianity on Moala itself, Lyth departed in optimistic mood, largely because of his confidence in Donu, “a very steady consistent man”.3 He observed that two young Moalan chiefs “who really ruled the land, remained determined haters of the truth”.4 On Matuku, which he also visited, all villages had accepted the lotu except the principal one, Dawaleka, to which Tui Nayau was vasu.5 The missionary’s qualified optimism was shattered in November when news reached Lakeba of an attack on Vunuku by the two chiefs opposed to the lotu. -

Severe Tc Gita (Cat4) Passes Just South of Ono

FIJI METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF FIJI MEDIA RELEASE No.35 5pm, Tuesday 13 February 2018 SEVERE TC GITA (CAT4) PASSES JUST SOUTH OF ONO Severe TC Gita (Category 4) entered Fiji Waters this morning and passed just south of Ono-i- lau at around 1.30pm this afternoon. Hurricane force winds of 68 knots and maximum momentary gusts of 84 knots were recorded at Ono-i-lau at 2pm this afternoon as TC Gita tracked westward. Vanuabalavu also recorded strong and gusty winds (Table 1). Severe “TC Gita” was located near 21.2 degrees south latitude and 178.9 degrees west longitude or about 60km south-southwest of Ono-i-lau or 390km southeast of Kadavu at 3pm this afternoon. It continues to move westward at about 25km/hr and expected to continue on this track and gradually turn west-southwest. On its projected path, Severe TC Gita is predicted to be located about 140km west-southwest of Ono-i-lau or 300km southeast of Kadavu around 8pm tonight. By 2am tomorrow morning, Severe TC Gita is expected to be located about 240km west-southwest of Ono-i-lau and 250km southeast of Kadavu and the following warnings remains in force: A “Hurricane Warning” remains in force for Ono-i-lau and Vatoa; A “Storm Warning” remains in force for the rest of Southern Lau group; A “Gale Warning” remains in force for Matuku, Totoya, Moala , Kadavu and nearby smaller islands and is now in force for Lakeba and Nayau; A “Strong Wind Warning” remains in force for Central Lau Group, Lomaiviti Group, southern half of Viti Levu and is now in force for rest of Fiji. -

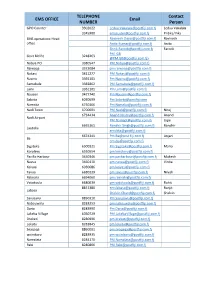

EMS Operations Centre

TELEPHONE Contact EMS OFFICE Email NUMBER Person GPO Counter 3302022 [email protected] Ledua Vakalala 3345900 [email protected] Pritika/Vika EMS operations-Head [email protected] Ravinesh office [email protected] Anita [email protected] Farook PM GB Govt Bld Po 3218263 @[email protected]> Nabua PO 3380547 [email protected] Raiwaqa 3373084 [email protected] Nakasi 3411277 [email protected] Nasinu 3392101 [email protected] Samabula 3382862 [email protected] Lami 3361101 [email protected] Nausori 3477740 [email protected] Sabeto 6030699 [email protected] Namaka 6750166 [email protected] Nadi Town 6700001 [email protected] Niraj 6724434 [email protected] Anand Nadi Airport [email protected] Jope 6665161 [email protected] Randhir Lautoka [email protected] 6674341 [email protected] Anjani Ba [email protected] Sigatoka 6500321 [email protected] Maria Korolevu 6530554 [email protected] Pacific Harbour 3450346 [email protected] Mukesh Navua 3460110 [email protected] Vinita Keiyasi 6030686 [email protected] Tavua 6680239 [email protected] Nilesh Rakiraki 6694060 [email protected] Vatukoula 6680639 [email protected] Rohit 8812380 [email protected] Ranjit Labasa [email protected] Shalvin Savusavu 8850310 [email protected] Nabouwalu 8283253 [email protected] -

Researchspace@Auckland

http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz ResearchSpace@Auckland Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: • Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. • Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of this thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. • You will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from their thesis. To request permissions please use the Feedback form on our webpage. http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/feedback General copyright and disclaimer In addition to the above conditions, authors give their consent for the digital copy of their work to be used subject to the conditions specified on the Library Thesis Consent Form and Deposit Licence. CONNECTING IDENTITIES AND RELATIONSHIPS THROUGH INDIGENOUS EPISTEMOLOGY: THE SOLOMONI OF FIJI ESETA MATEIVITI-TULAVU A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The University of Auckland Auckland, New Zealand 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .................................................................................................................................. vi Dedication ............................................................................................................................ -

Wansolwara, September 2011, 16(2)

Volume 16, No. 2 SEPTEMBER, 2011 Wansolwara An independent student newspaper and online publication Youth fund Report moots regional initiative to resolve lack of progress with the opportunities to associations to address the to the formal curriculum and by PARIJATA GURDAYAL propose projects that have a various youth issues. involve working closely with THERE is a need for a regional strong community focus. “Specifi c projects could be partners in the community, youth fund to provide youths “The absence of available funded to improve female and such as local government and with the needed resources to resources is a major reason male access to higher levels of church groups, it noted. INSIGHT address their issues. for the lack of progress at the education or basic literacy, or An alternative was for the This was one of the recom- regional country level in ad- providing more educational projects to be proposed and FORESTS are vital for the mendations in the State of Pa- dressing youth issues,” it said. or livelihood opportunities run by youth-led associations security of Pacifi c Island cifi c Youth 2011: Opportuni- The report proposes a for young people with HIV & that involve school leavers. ties and Obstacles report that system for addressing this gap AIDS, or physical or mental “The creation of links be- nations. Is enough being was released by the Secretar- through a regional agency such disabilities,” it said. tween communities should be iat of the Pacifi c Community as the SPC to set up a regional To attain a stronger commu- an important focus to lift the done to protect it? (SPC) and the United Nations youth challenge fund. -

Republic of the Fiji Islands State Cedaw 2Nd, 3Rd & 4Th Periodic Report

ANNEXES TO THE COMBINED SECOND, THIRD AND FOURTH PERIODIC REPORT OF FIJI (CEDAW/C/FJI/2-4) REPUBLIC OF THE FIJI ISLANDS STATE CEDAW 2ND, 3RD & 4TH PERIODIC REPORT NOVEMBER 2008 Annexes ANNEX 1 CONCLUDING COMMENTS CEDAW RECOMMENDATION AND STATUS OF IMPLEMENTATION in FIJI Concerns Recommendation Response 1.Constitution of 1997 does Proposed constitution In fact the Constitution covers not contain the definition of reform should address the ALL FORMS of Discrimination discrimination against women need to incorporate the in section 38(2). The definition of definition of discrimination discrimination is contained in the Human Rights Commission Act at section 17 (1) and (2). 2. Absence of effective The government to include The Human Rights Commission mechanisms to challenge a clear procedure for the Act 10/99 is Fiji’s EEO law- see discriminatory practices and enforcement of section 17 for application to the enforce the right to gender fundamental rights and private sphere and employment. equality guaranteed by the enact an EEO law to cover FHRC also handles complaints constitution in respect of the the actions of non-state by women on a range of issues. actions of public officials and actors. (Reports Attached as Annex 2). non-state actors. 3.CEDAW is not specified in Expansions of the FHRC’s NOT TRUE. FHRC has a broad, and the mandate of the Fiji Human mandate to include not specific, mandate and therefore Rights Commission and that its CEDAW and that the deals with all discrimination including not assured funds to continue commission is provided gender. In response to the Concluding its work with adequate resources Comments of the UN CEDAW from State funds. -

A Victorian Curate: a Study of the Life and Career of the Rev. Dr John Hunt

D A Victorian Curate A Study of the Life and Career of the Rev. Dr John Hunt DAVID YEANDLE AVID The Rev. Dr John Hunt (1827-1907) was not a typical clergyman in the Victorian Church of England. He was Sco� sh, of lowly birth, and lacking both social Y ICTORIAN URATE EANDLE A V C connec� ons and private means. He was also a wi� y and fl uent intellectual, whose publica� ons stood alongside the most eminent of his peers during a period when theology was being redefi ned in the light of Darwin’s Origin of Species and other radical scien� fi c advances. Hunt a� racted notoriety and confl ict as well as admira� on and respect: he was A V the subject of ar� cles in Punch and in the wider press concerning his clandes� ne dissec� on of a foetus in the crypt of a City church, while his Essay on Pantheism was proscribed by the Roman Catholic Church. He had many skirmishes with incumbents, both evangelical and catholic, and was dismissed from several of his curacies. ICTORIAN This book analyses his career in London and St Ives (Cambs.) through the lens of his autobiographical narra� ve, Clergymen Made Scarce (1867). David Yeandle has examined a li� le-known copy of the text that includes manuscript annota� ons by Eliza Hunt, the wife of the author, which off er unique insight into the many C anonymous and pseudonymous references in the text. URATE A Victorian Curate: A Study of the Life and Career of the Rev. -

Fifty Years of Studies in 1'\ Ethod1st History

Paoe•• DUCOI FIFTY YEARS OF STUDIES IN 1'\ ETHOD1ST HISTORY The Wesley Historical Society was established in 1893 and therefore celebrates its Jubilee this year. The early issues of the Proceedings were full of useful articles and studies for students of Methodist history. New letters of Wesley were constantly being found and corrections in the existing editions of Wesley's Journals and Letters were constantly being made. Indeed it can be safely said that we should never have had such admirable Standard Editions of both Letters and Journal but for the work of the Society. It was in the Proceedings that the suggestion was first made for the publication of these standard editions. These fifty years have seen notable achievements in the field of Methodist history. The most important of these have been the publication of the Standard Editions of Wesley's Journal (8 vols.) and Wesley's Letters. (8 vols.) and what has come to be regarded as the standard Life of John Wesley, that by Dr. J. S. Simon, in 5 vols. There is no man in English history of whose life the details are 80 fully known not only from year to year but for a great part of it from hour to hour as John Wesley; The Rev. W. B. Brash in the Didsbury College Centenary volume says "Apart from Birk beck Hill's editing of Boswell's Life of Samuel Johnson, it is the most carefully and fully edited book known to us in the field of English Literature." The Editor, Rev. Nehemiah Curnock, like so many other specialists in this period, was a Didsbury man. -

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago