Insisting on Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strange Bedfellows: Network Neutrality‘S Unifying Influence†

STRANGE BEDFELLOWS: NETWORK NEUTRALITY‘S UNIFYING INFLUENCE† Marvin Ammori* I want to talk about something called network (or ―net‖) neutrality. Let me begin, though, with a story involving short codes. For those unfamiliar with what a short code is, recall the voting process on American Idol and the little code that you can punch into your cell phone to vote for your favorite singer.1 Short codes are not ten digit numbers; rather, they are more like five or six.2 In theory, anyone can get a short code. Presidential candidates use short codes in their campaigns to communicate with their followers. For instance, a person could have signed up and Barack Obama would have sent them a message through a short code when he chose Joe Biden as his running mate.3 A few years ago, an abortion rights group called NARAL Pro-Choice America wanted a short code to communicate with its own followers.4 NARAL‘s goal was not to send ―spam‖; instead, the short code was directed to people who agreed with their message.5 Verizon rejected the idea of a short code for this group because, according to Verizon, NARAL was engaged in ―controversial‖ speech. The New York Times printed a front page article about this.6 Many people who read the story wondered if they really needed a permission slip from Verizon, or from anyone else, to communicate about political things that they care about. In response † This speech is adapted for publication and was originally presented at a panel discussion as part of the Regent University Law Review and The Federalist Society for Law & Public Policy Studies Media and Law Symposium at Regent University School of Law, October 9–10, 2009. -

Korn MP3 Collection Mp3, Flac, Wma

Korn MP3 Collection mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: MP3 Collection Country: Russia Style: Alternative Rock, Hardcore, Nu Metal MP3 version RAR size: 1479 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1820 mb WMA version RAR size: 1182 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 701 Other Formats: MP1 MMF AU RA FLAC AIFF MPC Tracklist Hide Credits 1994 - Korn 1 –Korn Blind 0:47 2 –Korn Ball Tongue 4:29 3 –Korn Need To 4:01 4 –Korn Clown 4:37 5 –Korn Divine 2:51 6 –Korn Faget 5:49 7 –Korn Shoots And Ladders 5:22 8 –Korn Predictable 4:32 9 –Korn Fake 4:51 10 –Korn Lies 3:22 11 –Korn Helmet In The Bush 4:02 Daddy 12A –Korn 17:31 Voice – Judith Kiener 12B –Korn Michael And Geri 1996 - Life Is Peachy 13 –Korn Twist 0:49 14 –Korn Chi 3:54 15 –Korn Lost 2:55 16 –Korn Swallow 3:38 17 –Korn Porno Creep 2:01 18 –Korn Good God 3:20 Mr. Rogers 19 –Korn 5:10 Guitar [Additional] – Jonathan Davis 20 –Korn K@#0%! 3:02 21 –Korn No Place To Hide 3:31 Wicked 22 –Korn 4:00 Vocals – Chino MorenoWritten-By – Ice Cube A.D.I.D.A.S. 23 –Korn 2:32 Vocals [Additional] – Baby Nathan Low Rider 24 –Korn 0:58 Cowbell – Chuck Johnson Written-By – War 25 –Korn Ass Itch 3:39 Kill You 26A –Korn 8:37 Guitar [Additional] – Jonathan Davis 26B –Korn Twist (A Capella) 1998 - Follow The Leader 27 –Korn It's On! 4:28 28 –Korn Freak On A Leash 4:15 29 –Korn Got The Life 3:45 30 –Korn Dead Bodies Everywhere 4:44 Children Of The Korn 31 –Korn 3:52 Featuring – Ice Cube 32 –Korn B.B.K 3:56 33 –Korn Pretty 4:12 All In The Family 34 –Korn 4:48 Featuring – Fred Durst 35 –Korn Reclaim My Place 4:32 -

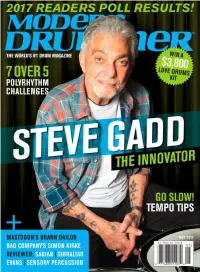

40 Steve Gadd Master: the Urgency of Now

DRIVE Machined Chain Drive + Machined Direct Drive Pedals The drive to engineer the optimal drive system. mfg Geometry, fulcrum and motion become one. Direct Drive or Chain Drive, always The Drummer’s Choice®. U.S.A. www.DWDRUMS.COM/hardware/dwmfg/ 12 ©2017Modern DRUM Drummer WORKSHOP, June INC. ALL2014 RIGHTS RESERVED. ROLAND HYBRID EXPERIENCE RT-30H TM-2 Single Trigger Trigger Module BT-1 Bar Trigger RT-30HR Dual Trigger RT-30K Learn more at: Kick Trigger www.RolandUS.com/Hybrid EXPERIENCE HYBRID DRUMMING AT THESE LOCATIONS BANANAS AT LARGE RUPP’S DRUMS WASHINGTON MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH CARLE PLACE CYMBAL FUSION 1504 4th St., San Rafael, CA 2045 S. Holly St., Denver, CO 11151 Veirs Mill Rd., Wheaton, MD 385 Old Country Rd., Carle Place, NY 5829 W. Sam Houston Pkwy. N. BENTLEY’S DRUM SHOP GUITAR CENTER HALLENDALE THE DRUM SHOP COLUMBUS PRO PERCUSSION #401, Houston, TX 4477 N. Blackstone Ave., Fresno, CA 1101 W. Hallandale Beach Blvd., 965 Forest Ave., Portland, ME 5052 N. High St., Columbus, OH MURPHY’S MUSIC GELB MUSIC Hallandale, FL ALTO MUSIC RHYTHM TRADERS 940 W. Airport Fwy., Irving, TX 722 El Camino Real, Redwood City, CA VIC’S DRUM SHOP 1676 Route 9, Wappingers Falls, NY 3904 N.E. Martin Luther King Jr. SALT CITY DRUMS GUITAR CENTER SAN DIEGO 345 N. Loomis St. Chicago, IL GUITAR CENTER UNION SQUARE Blvd., Portland, OR 5967 S. State St., Salt Lake City, UT 8825 Murray Dr., La Mesa, CA SWEETWATER 25 W. 14th St., Manhattan, NY DALE’S DRUM SHOP ADVANCE MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH HOLLYWOOD DRUM SHOP 5501 U.S. -

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

September 13, 2020

Vision: That all generations at St. Mary and in the surrounding community encounter Je- sus and live as His disci- ples. Mission: We are called to go out and share the Good News, making disciples who build up the Kingdom of God through meaningful prayer, effec- tive formation and loving ser- vice. SAINT MARY OF THE ANNUNCIATION MUNDELEIN Temporary Mass Schedule: www.stmaryfc.org TemporarySun. 7:30, Mass9:30,11:30 Schedule: AM Facebook:www.stmaryfc.org @stmarymundelein Sun.Tuesday, 7:30, 9:30,11:30 8:00 AM AM Facebook:Twitter: @stmarymundelein @stmarymundelein Wednesday,Tuesday, 8:00 8:00AM AM Instagram:Twitter: @stmarymundelein @stmarymundelein Thursday, 9:008:00 AM Instagram: @stmarymundelein Confessions: Saturday, 3:00–4:00 PM Confessions: Saturday, 3:00–4:00 PM Mass Intentions September 14—20, 2020 Stewardship Report Tuesday, September 15, 8:00 AM Living 69th Wedding Anniversary Sunday Collection September 6, 2020 $ 20,786..07 Matthew & Dorothy Miholic Budgeted Weekly Collection $ 22,115.38 Living Duane & Fran Schmidt Family Difference $ (1,329.31) †Salvatore & †Micheline Panettieri The Family †Genovera Larua Berner Family Current Fiscal Year-to-Date* $ 198,759.01 †Arthur “Artie” Sutko Victoria Hansen Budgeted Sunday Collections To-Date $ 221,153.85 †Archangel Capulong Wife Amy & Family †Lt. Keith O’Brien Difference $ (22,394.84) Difference vs. Last Year $ (31,220.12) Wednesday, September 16, 8:00AM †Lt. Keith O’ Brien *Note: YTD amount reflects updates by bank to postings and adjustments. †Liam Nold Gannon Family Thursday, September 17, 8:00 AM Living Lauren Jensen Shirley Monahan †Bob Soley Diana Suhling Join the Re-Opening Team †Karla Adams Parents Ed & Margaret Stahoviak The St. -

US Citizens As Enemy Combatants

Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development Volume 18 Issue 2 Volume 18, Spring 2004, Issue 2 Article 14 U.S. Citizens as Enemy Combatants: Indication of a Roll-Back of Civil Liberties or a Sign of our Jurisprudential Evolution? Joseph Kubler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcred This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. U.S. CITIZENS AS ENEMY COMBATANTS; INDICATION OF A ROLL-BACK OF CIVIL LIBERTIES OR A SIGN OF OUR JURISPRUDENTIAL EVOLUTION? JOSEPH KUBLER I. EXTRAORDINARY TIMES Exigent circumstances require our government to cross legal boundaries beyond those that are unacceptable during normal times. 1 Chief Justice Rehnquist has expressed the view that "[w]hen America is at war.., people have to get used to having less freedom."2 A tearful Justice Sandra Day O'Connor reinforced this view, a day after visiting Ground Zero, by saying that "we're likely to experience more restrictions on our personal freedom than has ever been the case in our country."3 However, extraordinary times can not eradicate our civil liberties despite their call for extraordinary measures. "Lawyers have a special duty to work to maintain the rule of law in the face of terrorism, Justice O'Connor said, adding in a quotation from Margaret 1 See Christopher Dunn & Donna Leiberman, Security v. -

ACLU BLC, Orlando June 12, 2011

ACLU BLC, Orlando June 12, 2011 “Taking Liberties: The ACLU and the War on Terror” During the first week of September 2001, the ACLU got a new Executive Director for the first time in over 20 years. Anthony Romero began work in our current building at 125 Broad Street in downtown Manhattan, a building the ACLU had been occupying for only a few years, having moved down from the Roger Baldwin building on West 43rd Street, in midtown Manhattan, in 1997. During the second week of that month, I don’t need to tell you that downtown Manhattan was devastated, New York City changed, the country changed, and the world changed. And so the ACLU staff, including our new ED, faced all sorts of challenges in adapting to living and working in this new, uncomfortable physical and psychological environment: how do you meet the payroll when everything you need is locked into a building you’re not allowed to enter, and how do you answer a swarm of press inquiries when, in those pre-iPhone days, the computers and telephone systems were inaccessible? One of Anthony’s first tasks was to arrange psychological counseling for some staff members who were traumatized by being so close to the World Trade Center on 9/11 and afterwards. And the entire organization faced the equally daunting challenge of evaluating and responding to the government’s responses to 9/11. By the end of October, less than six weeks after the events of 9/11, Congress had enacted the USA PATRIOT Act which, I will remind you, was an acronym, standing for Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools for Intercepting and Obstructing Terrorism. -

Theodore H. White Lecture on Press and Politics with Taylor Branch

Theodore H. White Lecture on Press and Politics with Taylor Branch 2009 Table of Contents History of the Theodore H. White Lecture .........................................................5 Biography of Taylor Branch ..................................................................................7 Biographies of Nat Hentoff and David Nyhan ..................................................9 Welcoming Remarks by Dean David Ellwood ................................................11 Awarding of the David Nyhan Prize for Political Journalism to Nat Hentoff ................................................................................................11 The 2009 Theodore H. White Lecture on Press and Politics “Disjointed History: Modern Politics and the Media” by Taylor Branch ...........................................................................................18 The 2009 Theodore H. White Seminar on Press and Politics .........................35 Alex S. Jones, Director of the Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy (moderator) Dan Balz, Political Correspondent, The Washington Post Taylor Branch, Theodore H. White Lecturer Elaine Kamarck, Lecturer in Public Policy, Harvard Kennedy School Alex Keyssar, Matthew W. Stirling Jr. Professor of History and Social Policy, Harvard Kennedy School Renee Loth, Columnist, The Boston Globe Twentieth Annual Theodore H. White Lecture 3 The Theodore H. White Lecture com- memorates the life of the reporter and historian who created the style and set the standard for contemporary -

Iowa State University Alumni Association

Dear Iowa State University Graduates and Guests: Congratulations to all of the Spring 2017 graduates of Iowa State University! We are very proud of you for the successful completion of your academic programs, and we are pleased to present you with a degree from Iowa State University recognizing this outstanding achievement. We also congratulate and thank everyone who has played a role in the graduates’ successful journey through this university, and we are delighted that many of you are here for this ceremony to share in their recognition and celebration. We have enjoyed having you as students at Iowa State, and we thank you for the many ways you have contributed to our university and community. I wish you the very best as you embark on the next part of your life, and I encourage you to continue your association with Iowa State as part of our worldwide alumni family. Iowa State University is now in its 159th year as one of the nation’s outstanding land-grant universities. We are very proud of the role this university has played in preparing the future leaders of our state, nation, and world, and in meeting the needs of our society through excellence in education, research, and outreach. As you graduate today, you are now a part of this great tradition, and we look forward to the many contributions you will make. I hope you enjoy today’s commencement ceremony. We wish you all continued success! Sincerely, Steven Leath President of the University TABLE OF CONTENTS The Official University Mace .......................................................................................................... 4 The Presidential Chain of Office .................................................................................................... -

Nazi Crimes on People with Disabilities in the Light of International Law – a Brief Review

Białostockie Studia Prawnicze 2018 vol. 23 nr 4 DOI: 10.15290/bsp.2018.23.04.16 Sylwia Afrodyta Karowicz-Bienias University of Bialystok [email protected] ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8992-1540 Nazi Crimes on People with Disabilities in the Light of International Law – a Brief Review Abstract: Th e cruelty of crimes committed by the Nazis during World War II is beyond belief. Ethnic cleansing focused mainly on the Jewish community and has been spoken of the loudest since the end of the war, but this was not the only course of eugenic thought. People who had been harmed by birth – the disabled and mentally ill, were not spared the torturers wearing German uniforms. Th is article presents the circumstances involved relating to the activities of AktionT4 in Germany and the territories under German occupation, and performs a legal analysis of these activities in the light of international law in the so-called Doctors’ Trial, the fi rst of the follow-up processes to Th e Nuremburgh Trial. Th e author in- troduces the legal bases of the sentences issued in the trial and highlights the process of shaping the re- sponsibility of individuals in international law. Th e participation of Polish law enforcement agencies in prosecuting crimes against humanity committed on the patients of psychiatric hospitals and care centers in Poland, is also addressed. Th e proceedings in this case have been ongoing to this day, now conducted under the auspices of the Institute of National Remembrance. Key words: Nazi crimes, World War II, crimes against humanity, international law, Nuremberg trial, Doctors’ Trial, disability, Aktion T4. -

His Prophecy Has Proven Accurate; the Post- 1914 Years Have Been an Era of Total War and the Total State

1 2 During World War I, American activist Randolph Bourne had warned, "War is the health of the State."1 His prophecy has proven accurate; the post- 1914 years have been an era of total war and the total state. It had seemed that with the fall of the Soviet Union, the state of permanent war, permanent mobilization, and permanent emergency would end. This hope has not been realized. Instead, the US and the world are now laying the groundwork for high-tech totalitarianism; liberty is in retreat, just as occurred almost everywhere between 1914 and 1945. Precedents from the 1790s through World War II Federal power grabs have been a bi-partisan policy, long before the War on Terror. All of these acts have created precedents for what is being done or proposed now. In 1798, the Federal Government passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, in response to the threat of war with France.2 "The Sedition Act made it a criminal offense to print or publish false, malicious, or scandalous statements directed against the U.S. government, the president, or Congress; to foster opposition to the lawful acts of Congress; or to aid a foreign power in plotting against the United States."3 About 25 people were arrested under the law, and 10 were imprisoned. The Sedition Act had an 1801 expiration date, and appeared to be designed to impede opposition party political activity and journalism in the 1800 Presidential election. These laws were unpopular, and the reaction to them helped win the 1800 election for Thomas Jefferson. -

2014 Journal

fellowships at auschwitz for the study of professional ethics professional the study of auschwitz for at fellowships | 2014 journal 2014 Journal faspe operates Under the auspices of www.faspe.info 2014 Journal With special thanks to Professor Dale Maharidge, Professor Andie Tucher, Professor Belinda Cooper, Professor Eric Muller, Dr. Sarah Goldkind, Dr. Mark Mercurio, Professor Kevin Spicer, Professor LeRoy Walters, and Rabbi Nancy Wiener. Lead support for FASPE is provided by C. David 2014 Goldman, Frederick and Margaret Marino, and the Eder Journal Family Foundation. Additional support has been provided by The Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany. E DITOR T HORIN R. TRITT E R , PH .D. A SSIST A NT EDITOR T A LI A BLOCH C OV E R P HOTOS COURT E SY OF 2014 FASPE FE LLOWS T HIS JOURN A L H A S bee N P R epa R E D B Y FASPE IN CONJUNCTION WITH TH E M US E U M OF JE WISH HE RIT A G E —A LIVING Mem ORI A L TO TH E HOLOC A UST . © FASPE/MUS E U M OF JE WISH HE RIT A G E 2014 Journal steering committee Jolanta Ambrosewicz-Jacobs, Director, Anthony Kronman, Sterling Professor The Center for Holocaust Studies, of Law, Yale Law School Jagiellonian University Tomasz Kuncewicz, Director, Dr. Nancy Angoff, Associate Dean Auschwitz Jewish Center for Student Affairs, Yale School of Medicine John Langan, S.J., Cardinal Bernardin Ivy Barsky, Director, National Museum Professor of Catholic Social Thought, of American Jewish History Georgetown University Andrea Bartoli, Dean, School of Diplomacy Frederick Marino and International Relations, Seton Hall University David G.