ABSTRACT Visual Political Brand Identities in the 2018 U.S. Midterm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Progressive Victories Lay the Groundwork for 2020

A SPECIAL PUBLICATION OF Progressive Victories Lay the classmates and teachers were gunned down in February -- spent the summer and fall traveling the Groundwork for 2020 country for the “Road To Change’’ tour urging people to register to vote. No group played as important a role as Indivisible, founded soon after By Peter Dreier Trump’s election, which quickly expanded to every Congressional district, training and mobilizing first- Politics is a struggle for power – over ideas and time activists and new leaders in the skills of issue interests – and after this year’s midterm elections organizing and campaign work. two things remain clear. First, voter suppression and intimidation, racism, and corporate money Women, young people, African Americans, and continue to infect American politics like a virus. Latinos turned out in significantly higher numbers Second, despite those obstacles, America is a much than they did in the previous midterm election in more progressive country than most pundits and 2014 – reflecting an anti-Trump backlash and the political analysts believe. Voters embraced many enthusiasm triggered by competitive races. Not progressive candidates and ballot measures, even in surprisingly, the election saw an upsurge of women, so-called conservative states and Congressional LGBT people, African Americans, and Latinos districts. elected to office. The midterm victories give Democrats an The U.S. House of Representatives opportunity to thwart much of Donald Trump’s agenda, to investigate his and his administration’s In the 435 House races, Democrats outpolled corruption, and to put forward a progressive policy Republicans by 55,2 million to 49.2 million votes. -

Congressional Report Card

Congressional Report Card NOTE FROM BRIAN DIXON Senior Vice President for Media POPULATION CONNECTION and Government Relations ACTION FUND 2120 L St NW, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20037 ou’ll notice that this year’s (202) 332–2200 Y Congressional Report Card (800) 767–1956 has a new format. We’ve grouped [email protected] legislators together based on their popconnectaction.org scores. In recent years, it became twitter.com/popconnect apparent that nearly everyone in facebook.com/popconnectaction Congress had either a 100 percent instagram.com/popconnectaction record, or a zero. That’s what you’ll popconnectaction.org/116thCongress see here, with a tiny number of U.S. Capitol switchboard: (202) 224-3121 exceptions in each house. Calling this number will allow you to We’ve also included information connect directly to the offices of your about some of the candidates senators and representative. that we’ve endorsed in this COVER CARTOON year’s election. It’s a small sample of the truly impressive people we’re Nick Anderson editorial cartoon used with supporting. You can find the entire list at popconnectaction.org/2020- the permission of Nick Anderson, the endorsements. Washington Post Writers Group, and the Cartoonist Group. All rights reserved. One of the candidates you’ll read about is Joe Biden, whom we endorsed prior to his naming Sen. Kamala Harris his running mate. They say that BOARD OF DIRECTORS the first important decision a president makes is choosing a vice president, Donna Crane (Secretary) and in his choice of Sen. Harris, Joe Biden struck gold. Carol Ann Kell (Treasurer) Robert K. -

Big Business and Conservative Groups Helped Bolster the Sedition Caucus’ Coffers During the Second Fundraising Quarter of 2021

Big Business And Conservative Groups Helped Bolster The Sedition Caucus’ Coffers During The Second Fundraising Quarter Of 2021 Executive Summary During the 2nd Quarter Of 2021, 25 major PACs tied to corporations, right wing Members of Congress and industry trade associations gave over $1.5 million to members of the Congressional Sedition Caucus, the 147 lawmakers who voted to object to certifying the 2020 presidential election. This includes: • $140,000 Given By The American Crystal Sugar Company PAC To Members Of The Caucus. • $120,000 Given By Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy’s Majority Committee PAC To Members Of The Caucus • $41,000 Given By The Space Exploration Technologies Corp. PAC – the PAC affiliated with Elon Musk’s SpaceX company. Also among the top PACs are Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, and the National Association of Realtors. Duke Energy and Boeing are also on this list despite these entity’s public declarations in January aimed at their customers and shareholders that were pausing all donations for a period of time, including those to members that voted against certifying the election. The leaders, companies and trade groups associated with these PACs should have to answer for their support of lawmakers whose votes that fueled the violence and sedition we saw on January 6. The Sedition Caucus Includes The 147 Lawmakers Who Voted To Object To Certifying The 2020 Presidential Election, Including 8 Senators And 139 Representatives. [The New York Times, 01/07/21] July 2021: Top 25 PACs That Contributed To The Sedition Caucus Gave Them Over $1.5 Million The Top 25 PACs That Contributed To Members Of The Sedition Caucus Gave Them Over $1.5 Million During The Second Quarter Of 2021. -

Military Family Caucus 2020SUMMIT Military Families in the Time of COVID

VIRTUAL Military Family Caucus 2020SUMMIT Military Families in the Time of COVID October 9, 2020 Hosted By: Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers and Rep. Sanford D. Bishop, Jr. CONGRESSIONAL MFC Military Family Summit October 9, 2020 SCHEDULE 9:30 - 10:00am PDT Opening Remarks: Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers Rep. Sanford Bishop Col. Cassius Bentley 10:00 -10:10am Secretary of Defense Mark Esper 10:10 - 10:30am Under Secretary Matthew Donovan 10:30 - 11:00am Education 11:00 - 11:30am Special Education 11:30 - 12:00pm Exceptional Family Member Program 12:00 - 12:30pm Permanent Change of Station 12:30 - 1:00pm Childcare 1:00 - 1:30pm Healthcare 1:30 - 2:00pm Housing 2:00 - 2:30pm Spouse Employment/Licensing 2:30 - 3:00pm Military Retirement/Transitioning/Separation 3:00pm Closing remarks CONGRESSIONAL MFC Military Family Summit October 9, 2020 OPENING REMARKS Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers (WA-05) Congresswoman Cathy McMorris Rodgers is Eastern Washington’s chief advocate in Congress. As co-chair of the Military Family Caucus, Cathy has led to raise troop pay, boost military funding, and help Fairchild Air Force Base become the largest tanker base in America. She was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 2004. For nine terms, she has earned the trust of her constituents and praise on Capitol Hill for her hard work, conservative principles, bipartisan outreach, and ability to get results. As someone who grew up on an orchard and fruit stand in Kettle Falls, Washington, worked at her family’s small business, and later became a wife and working mom of three, Cathy has lived the American Dream. -

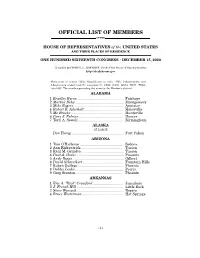

Official List of Members

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS • DECEMBER 15, 2020 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives http://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (233); Republicans in italic (195); Independents and Libertarians underlined (2); vacancies (5) CA08, CA50, GA14, NC11, TX04; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Bradley Byrne .............................................. Fairhope 2 Martha Roby ................................................ Montgomery 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................ -

MISSISSIPPI FAH MEMBER FACILITIES Federation of American Hospitals Represents America’S Tax-Paying SENATE Community Hospitals and Sen

MISSISSIPPI FAH MEMBER FACILITIES Federation of American Hospitals represents America’s tax-paying SENATE community hospitals and Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith (R) health systems. Sen. Roger Wicker (R) HOUSE (Click name to view the district) Rep. Trent Kelly (R) / Mississippi 1st Rep. Bennie Thompson (D) / Mississippi 2nd Rep. Michael Guest (R) / Mississippi 3rd Rep. Steven Palazzo (R) / Mississippi 4th TOTAL FACILITIES 17 TOTAL HOSPITAL BEDS 2,701 TOTAL EMPLOYEES 6,992 FEDERATION OF AMERICAN HOSPITALS® 750 9th Street, N.W. Suite 600, Washington, DC 20001 fah.org MISSISSIPPI FAH MEMBER FACILITIES Beds Employees REP. TRENT KELLY (R) / MISSISSIPPI 1ST 3 HOSPITALS Diamond Grove Center for Children Louisville Universal Health Services, Inc. 55 142 Northwest Mississippi Regional Medical Center Clarksdale Community Health Systems 181 Parkwood Behavioral Health System Olive Branch Universal Health Services, Inc. 148 284 REP. BENNIE THOMPSON (D) / MISSISSIPPI 2ND 4 HOSPITALS Bolivar Medical Center Cleveland LifePoint Health 199 495 Merit Health Central Jackson Community Health Systems 429 868 Merit Health Madison Canton Community Health Systems 67 272 Merit Health River Region Vicksburg Community Health Systems 372 732 REP. MICHAEL GUEST (R) / MISSISSIPPI 3RD 6 HOSPITALS Alliance Health Center Meridian Universal Health Services, Inc. 214 360 Brentwood Behavioral Healthcare of Mississippi Flowood Universal Health Services, Inc. 121 261 Merit Health Natchez Natchez Community Health Systems 179 511 Merit Health Rankin Brandon Community Health Systems 149 294 Merit Health River Oaks Flowood Community Health Systems 160 662 Merit Health Woman's Hospital Jackson Community Health Systems 109 213 REP. STEVEN PALAZZO (R) / MISSISSIPPI 4TH 4 HOSPITALS Encompass Health Rehabilitation Hospital, a partner of Gulfport Encompass Health Memorial Hospital at Gulfport Gulfport Behavioral Health System Gulfport Universal Health Services, Inc. -

How America's Federalized Labor

SOLIDARITY’S WEDGE: HOW AMERICA’S FEDERALIZED LABOR LAW DIVIDES AND DIMINISHES ORGANIZED LABOR IN THE UNITED STATES A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Alexis Nicole Walker May 2014 © 2014 Alexis Nicole Walker SOLIDARITY’S WEDGE: HOW AMERICA’S FEDERALIZED LABOR LAW DIVIDES AND DIMINISHES ORGANIZED LABOR IN THE UNITED STATES Alexis Nicole Walker, Ph. D. Cornell University 2014 Organized labor is one of the largest voluntary organizations in the United States, representing over 14 million members in a sophisticated network of local, state and national unions interconnected through labor councils, state organizations, and national federations that mount significant electoral and lobbying campaigns. Despite these apparent strengths, organized labor has suffered numerous setbacks including the continued failure to pass national labor law reform and the retrenchment of public sector collective bargaining rights in Wisconsin, which suggest they are less politically effective than we would expect given their membership and resources. Why does organized labor punch below its weight in American politics? This project emphasizes the important role of institutions—namely divided labor law and federalism—in shaping the composition, size, strength and effectiveness of organized labor in the American politics. Exclusion of public sector employees from the foundation of private sector labor law, the Wagner Act, or their own comparable national level law, firmly situated private sector law at the national level while relegating public sector employees’ efforts to gain collective bargaining rights to the state and local level. -

115Th Congress Roster.Xlsx

State-District 114th Congress 115th Congress 114th Congress Alabama R D AL-01 Bradley Byrne (R) Bradley Byrne (R) 248 187 AL-02 Martha Roby (R) Martha Roby (R) AL-03 Mike Rogers (R) Mike Rogers (R) 115th Congress AL-04 Robert Aderholt (R) Robert Aderholt (R) R D AL-05 Mo Brooks (R) Mo Brooks (R) 239 192 AL-06 Gary Palmer (R) Gary Palmer (R) AL-07 Terri Sewell (D) Terri Sewell (D) Alaska At-Large Don Young (R) Don Young (R) Arizona AZ-01 Ann Kirkpatrick (D) Tom O'Halleran (D) AZ-02 Martha McSally (R) Martha McSally (R) AZ-03 Raúl Grijalva (D) Raúl Grijalva (D) AZ-04 Paul Gosar (R) Paul Gosar (R) AZ-05 Matt Salmon (R) Matt Salmon (R) AZ-06 David Schweikert (R) David Schweikert (R) AZ-07 Ruben Gallego (D) Ruben Gallego (D) AZ-08 Trent Franks (R) Trent Franks (R) AZ-09 Kyrsten Sinema (D) Kyrsten Sinema (D) Arkansas AR-01 Rick Crawford (R) Rick Crawford (R) AR-02 French Hill (R) French Hill (R) AR-03 Steve Womack (R) Steve Womack (R) AR-04 Bruce Westerman (R) Bruce Westerman (R) California CA-01 Doug LaMalfa (R) Doug LaMalfa (R) CA-02 Jared Huffman (D) Jared Huffman (D) CA-03 John Garamendi (D) John Garamendi (D) CA-04 Tom McClintock (R) Tom McClintock (R) CA-05 Mike Thompson (D) Mike Thompson (D) CA-06 Doris Matsui (D) Doris Matsui (D) CA-07 Ami Bera (D) Ami Bera (D) (undecided) CA-08 Paul Cook (R) Paul Cook (R) CA-09 Jerry McNerney (D) Jerry McNerney (D) CA-10 Jeff Denham (R) Jeff Denham (R) CA-11 Mark DeSaulnier (D) Mark DeSaulnier (D) CA-12 Nancy Pelosi (D) Nancy Pelosi (D) CA-13 Barbara Lee (D) Barbara Lee (D) CA-14 Jackie Speier (D) Jackie -

Hearing on the Costs of Climate Change: from Coasts to Heartland, Health to Security

HEARING ON THE COSTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE: FROM COASTS TO HEARTLAND, HEALTH TO SECURITY HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE BUDGET HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION HEARING HELD IN WASHINGTON, D.C., JULY 24, 2019 Serial No. 116–13 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Budget ( Available on the Internet: www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 37–724 WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Mar 15 2010 13:01 Oct 22, 2019 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 T:\FY 2020\COMMITTEE REPORTS\HEARING REPORTS\7.24.19 THE COSTS OF CLIMAT BU00-A363290 with DISTILLER COMMITTEE ON THE BUDGET JOHN A. YARMUTH, Kentucky, Chairman SETH MOULTON, Massachusetts, STEVE WOMACK, Arkansas, Vice Chairman Ranking Member HAKEEM S. JEFFRIES, New York ROB WOODALL, Georgia BRIAN HIGGINS, New York BILL JOHNSON, Ohio, BRENDAN F. BOYLE, Pennsylvania Vice Ranking Member RO KHANNA, California JASON SMITH, Missouri ROSA L. DELAURO, Connecticut BILL FLORES, Texas LLOYD DOGGETT, Texas GEORGE HOLDING, North Carolina DAVID E. PRICE, North Carolina CHRIS STEWART, Utah JANICE D. SCHAKOWSKY, Illinois RALPH NORMAN, South Carolina DANIEL T. KILDEE, Michigan KEVIN HERN, Oklahoma JIMMY PANETTA, California CHIP ROY, Texas JOSEPH D. MORELLE, New York DANIEL MEUSER, Pennsylvania STEVEN HORSFORD, Nevada WILLIAM R. TIMMONS IV, South Carolina ROBERT C. ‘‘BOBBY’’ SCOTT, Virginia DAN CRENSHAW, Texas SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas TIM BURCHETT, Tennessee BARBARA LEE, California PRAMILA JAYAPAL, Washington ILHAN OMAR, Minnesota ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey SCOTT H. PETERS, California JIM COOPER, Tennessee PROFESSIONAL STAFF ELLEN BALIS, Staff Director DAN KENIRY, Minority Staff Director (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 13:01 Oct 22, 2019 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 T:\FY 2020\COMMITTEE REPORTS\HEARING REPORTS\7.24.19 THE COSTS OF CLIMAT BU00-A363290 with DISTILLER CONTENTS Page Hearing held in Washington D.C., July 24, 2019 ................................................ -

2019 Kraftheinzpac Contributions

The Kraft Heinz Company – 2019 KraftHeinzPAC Contributions State Candidate / Organization Amount Office Sought Alabama Robert Aderholt $1,000 House Arkansas John Boozman $2,000 Senate Jim Costa $5,000 House California Devin Nunes $1,000 House Nancy Pelosi $1,000 House Florida Al Lawson $3,500 House Cheri Bustos $1,000 House Danny Davis $2,500 House Illinois Rodney Davis $2,500 House Dick Durbin $2,500 Senate Brad Schneider $2,500 House Indiana Jim Banks $1,000 House Iowa Joni Ernst $2,500 Senate Kentucky Mitch McConnell $1,500 Senate Maryland Steny Hoyer $1,000 House Michigan Debbie Dingell $2,500 House Jim Hagedorn $1,000 House Minnesota Collin Peterson $2,500 House Tina Smith $1,000 Senate Sam Graves $2,000 House Missouri William (Billy) Long $2,500 House Jason Smith $1,000 House Ohio Robert (Bob) Gibbs $2,000 House Oregon Kurt Schrader $1,000 House Mike Doyle $2,000 House Pennsylvania Pat Toomey $1,000 Senate Mike Conaway $1,000 House Texas John Cornyn $2,500 Senate Virginia Jennifer Wexton $2,500 House Sean Duffy $1,000 House Wisconsin Ron Johnson $1,000 Senate Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee $5,000 Not Applicable Other National Republican Congressional Committee $5,000 Not Applicable New Democrat Coalition Action Fund $2,500 Not Applicable Republican Mainstreet Partnership PAC $5,000 Not Applicable Updated: January 2020 Note: Kraft Heinz and the Kraft Heinz PAC do not support Presidential campaigns, judicial candidates, super PACs or make contributions to independent expenditure committees, which is defined as money spent to support a political candidate, but not at the suggestion or request of the candidate, the candidate’s authorized committee or a political party. -

Working Families Party Endorses Randy Bryce For

WORKING FAMILIES PARTY ENDORSES RANDY BRYCE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 13, 2017 Contact: David Keith, (323)400-8853, [email protected] KENOSHA—Today, on the heels of the endorsement from multiple Democratic State Legislators, the Working Families Party endorsed Randy Bryce for Congress. "The people deserve a voice, workers deserve a voice, families deserve a voice. That's why I'm a proud member of the Working Families Party in Wisconsin and why I'm throwing my hard hat into the ring to run for Congress,” said Randy Bryce. “These issues aren't a game to me. I don't know what I'll do if my mom loses her healthcare. I'm running to make sure Southeastern Wisconsin gets a fair shake and I'm proud to have the backing of the WFP." The Working Families Party joins a growing list of national progressive organizations in supporting Bryce’s insurgent campaign. To see the official release from the Working Families Party, please see below. ### WORKING FAMILIES PARTY ANNOUCNES ENDORSEMENT FOR RANDY BRYCE FOR CONGRESS Growing momentum for insurgent candidate as key progressive group jumps in calling him: “A Hero for Working Families” For immediate release. For more information, contact: Joe Dinkin (WFP) at 978 223-5868 or [email protected] David Keith (Randy Bryce for Congress) at 323 400-8853 or [email protected] Today, the Wisconsin Working Families Party announced its endorsement for Randy Bryce, the union ironworker and veteran running an insurgent and inspiring campaign for Congress against House Speaker Paul Ryan. The endorsement marks the WFP’s first federal endorsement of the 2018 cycle in the nation, with WFP organizers pledging to make Bryce’s candidacy a top priority, and is a show of momentum for the campaign. -

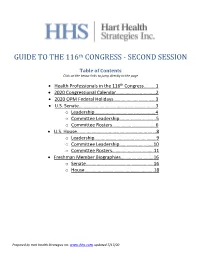

GUIDE to the 116Th CONGRESS

th GUIDE TO THE 116 CONGRESS - SECOND SESSION Table of Contents Click on the below links to jump directly to the page • Health Professionals in the 116th Congress……….1 • 2020 Congressional Calendar.……………………..……2 • 2020 OPM Federal Holidays………………………..……3 • U.S. Senate.……….…….…….…………………………..…...3 o Leadership…...……..…………………….………..4 o Committee Leadership….…..……….………..5 o Committee Rosters……….………………..……6 • U.S. House..……….…….…….…………………………...…...8 o Leadership…...……………………….……………..9 o Committee Leadership……………..….…….10 o Committee Rosters…………..…..……..…….11 • Freshman Member Biographies……….…………..…16 o Senate………………………………..…………..….16 o House……………………………..………..………..18 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 7/17/20 Health Professionals Serving in the 116th Congress The number of healthcare professionals serving in Congress increased for the 116th Congress. Below is a list of Members of Congress and their area of health care. Member of Congress Profession UNITED STATES SENATE Sen. John Barrasso, MD (R-WY) Orthopaedic Surgeon Sen. John Boozman, OD (R-AR) Optometrist Sen. Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA) Gastroenterologist/Heptalogist Sen. Rand Paul, MD (R-KY) Ophthalmologist HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Rep. Ralph Abraham, MD (R-LA-05)† Family Physician/Veterinarian Rep. Brian Babin, DDS (R-TX-36) Dentist Rep. Karen Bass, PA, MSW (D-CA-37) Nurse/Physician Assistant Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA-07) Internal Medicine Physician Rep. Larry Bucshon, MD (R-IN-08) Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX-26) Obstetrician Rep. Buddy Carter, BSPharm (R-GA-01) Pharmacist Rep. Scott DesJarlais, MD (R-TN-04) General Medicine Rep. Neal Dunn, MD (R-FL-02) Urologist Rep. Drew Ferguson, IV, DMD, PC (R-GA-03) Dentist Rep. Paul Gosar, DDS (R-AZ-04) Dentist Rep.