Final Gold Mountain Road Repair Environmental Assessment Mt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suspended-Sediment Concentration in the Sauk River, Washington, Water Years 2012-13

Prepared in cooperation with the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe Suspended-Sediment Concentration in the Sauk River, Washington, Water Years 2012-13 By Christopher A. Curran1, Scott Morris2, and James R. Foreman1 1 U.S. Geological Survey, Washington Water Science Center, Tacoma, Washington 2 Department of Natural Resources, Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe, Darrington, Washington Photograph of glacier-derived suspended sediment entering the Sauk River immediately downstream of the Suiattle River mouth (August 5, 2014, Chris Curran). iii Introduction The Sauk River is one of the few remaining large, glacier-fed rivers in western Washington that is unconstrained by dams and drains a relatively undisturbed landscape along the western slope of the Cascade Range. The river and its tributaries are important spawning ground and habitat for endangered Chinook salmon (Beamer and others, 2005) and also the primary conveyors of meltwater and sediment from Glacier Peak, an active volcano (fig. 1). As such, the Sauk River is a significant tributary source of both fish and fluvial sediment to the Skagit River, the largest river in western Washington that enters Puget Sound. Because of its location and function, the Sauk River basin presents a unique opportunity in the Puget Sound region for studying the sediment load derived from receding glaciers and the potential impacts to fish spawning and rearing habitat, and downstream river-restoration and flood- control projects. The lower reach of the Sauk River has some of the highest rates of incubation mortality for Chinook salmon in the Skagit River basin, a fact attributed to unusually high deposition of fine-grained sediments (Beamer, 2000b). -

Skagit River Emergency Bank Stabilization And

United States Department of the Interior FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Washington Fish and Wildlife Office 510 Desmond Dr. SE, Suite 102 Lacey, Washington 98503 In Reply Refer To: AUG 1 6 2011 13410-2011-F-0141 13410-2010-F-0175 Daniel M. Mathis, Division Adnlinistrator Federal Highway Administration ATIN: Jeff Horton Evergreen Plaza Building 711 Capitol Way South, Suite 501 Olympia, Washington 98501-1284 Michelle Walker, Chief, Regulatory Branch Seattle District, Corps of Engineers ATIN: Rebecca McAndrew P.O. Box 3755 Seattle, Washington 98124-3755 Dear Mr. Mathis and Ms. Walker: This document transmits the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Biological Opinion (Opinion) based on our review of the proposed State Route 20, Skagit River Emergency Bank Stabilization and Chronic Environmental Deficiency Project in Skagit County, Washington, and its effects on the bull trout (Salve linus conjluentus), marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus), northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina), and designated bull trout critical habitat, in accordance with section 7 of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.) (Act). Your requests for initiation of formal consultation were received on February 3, 2011, and January 19,2010. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers - Seattle District (Corps) provided information in support of "may affect, likely to adversely affect" determinations for the bull trout and designated bull trout critical habitat. On April 13 and 14, 2011, the FHWA and Corps gave their consent for addressing potential adverse effects to the bull trout and bull trout critical habitat with a single Opinion. -

Franklinwesleyearlynne1975

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF WESLEY EARLYNNE FRANKLIN for the degree Master of Science (Name of student) (Degree) in Geology presented on November 22, 1974 (Major department) (Date) Title: STRUCTURAL SIGNIFICANCE OF META-IGNEOUS FRAGMENTS IN THE PRAIRIE MOUNTAIN AREA, NORTH CASCADE RANGE, SNOHOMISH COUNTY, WASHINGTON Abstract approved by: Redacted for privacy Dr. Robert ID. Lawrence The interrelationship of rock assemblages in the Prairie Mountain area suggests that a Permo-Triassic subduction zone existed in the western North Cascades.The2fsquare mile rneta- igneous complex in the thesis area correlates with other tectonic bodies which occur west of the Straight Creek Fault.The rocks are uniquely associated with thrust faulting, a blueschist terrane and a possible melange of deformed Late Paleozoic sediments and meta- sediments.In the Prairie Mountain area the meta.- igneous rocks were emplaced by thrust and high-angle reversefaults into the Late Paleozoic Chilliwack Group.The meta-igneous rocks are metadio- rites, meta- quartz diorites, metatrondlijemites, mylonite gneis ses, rare greenstone metavoLcanic s and metamorphosed ultramafi.c s. Though the rocks were metamorphosed to the greenschist facies, only locally do they display a strong metamorphic fabric. A weak secondary cataclastic overprint resulting from ucoldtt intrusion is superimposed on the meta-igneous rocks. The meta-igneous rocks possibly represent fragments of island arc crust and/or oceanic crust that were incorporated into a Permo- Triassic subductj.on zone from a position -

Where the Water Meets the Land: Between Culture and History in Upper Skagit Aboriginal Territory

Where the Water Meets the Land: Between Culture and History in Upper Skagit Aboriginal Territory by Molly Sue Malone B.A., Dartmouth College, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Anthropology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Molly Sue Malone, 2013 Abstract Upper Skagit Indian Tribe are a Coast Salish fishing community in western Washington, USA, who face the challenge of remaining culturally distinct while fitting into the socioeconomic expectations of American society, all while asserting their rights to access their aboriginal territory. This dissertation asks a twofold research question: How do Upper Skagit people interact with and experience the aquatic environment of their aboriginal territory, and how do their experiences with colonization and their cultural practices weave together to form a historical consciousness that orients them to their lands and waters and the wider world? Based on data from three methods of inquiry—interviews, participant observation, and archival research—collected over sixteen months of fieldwork on the Upper Skagit reservation in Sedro-Woolley, WA, I answer this question with an ethnography of the interplay between culture, history, and the land and waterscape that comprise Upper Skagit aboriginal territory. This interplay is the process of historical consciousness, which is neither singular nor sedentary, but rather an understanding of a world in flux made up of both conscious and unconscious thoughts that shape behavior. I conclude that the ways in which Upper Skagit people interact with what I call the waterscape of their aboriginal territory is one of their major distinctive features as a group. -

WDFW Wildlife Program Bi-Weekly Report August 1-15, 2020

Wildlife Program – Bi-weekly Report August 1 to August 15, 2020 DIVERSITY DIVISION HERE’S WHAT WE’VE BEEN UP: 1) Managing Wildlife Populations Fishers: Fisher reintroduction project partners from Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, the National Park Service, Conservation Northwest, Calgary Zoo, and United States Forest Service recently initiated a genetic analysis of fishers to predict the effect of augmenting ten new fishers to Olympic National Park. One main goal of the analysis is to determine how the success of the augmentation could differ depending on whether the fishers came from British Columbia versus; two genetically different source-populations. Using existing genotypes from British Columbia and Alberta fishers, this analysis will provide insights into the best source population of fishers to use for the planned augmentation to the Olympic National Park, where 90 fishers from British Columbia were reintroduced from 2008 to 2010. A 2019 genetic analysis of fishers on the Olympic Peninsula (based on hair samples collected at baited hair-snare and camera stations from 2013-2016) indicated that genetic diversity of the Olympic fisher population had declined slightly and would be expected to decline further in the future, which could put that population at risk. An augmentation of new fishers could restore this genetic diversity and this new analysis of the effects of releasing more British Columbia versus Alberta fishers into this population will help us decide the best source population and the best implementation approach. 2) Providing Recreation Opportunities Nothing for this installment. 3) Providing Conflict Prevention and Education Nothing for this installment. 4) Conserving Natural Areas Nothing for this installment. -

SKAGIT COOPERATIVE WEED MANAGEMENT AREA Upper Skagit Knotweed Control Program 2013 Season Ending Report

SKAGIT COOPERATIVE WEED MANAGEMENT AREA Upper Skagit Knotweed Control Program 2013 Season Ending Report Sauk River during 2013 knotweed surveys. Prepared by: Michelle Murphy Stewardship Manager Skagit Fisheries Enhancement Group PO Box 2497 Mount Vernon, WA 98273 Introduction In the 2013 season, the Skagit Fisheries Enhancement Group (SFEG) and our partners with the Skagit Cooperative Weed Management Area (CWMA) or Skagit Knotweed Working Group, completed extensive surveys of rivers and streams in the Upper Skagit watershed, treating knotweed in a top-down, prioritized approach along these waterways, and monitoring a large percentage of previously recorded knotweed patches in the Upper Skagit watershed. We continued using the prioritization strategy developed in 2009 to guide where work is completed. SFEG contracted with the Washington Conservation Corps (WCC) crew and rafting companies to survey, monitor and treat knotweed patches. In addition SFEG was assisted by the DNR Aquatics Puget Sound Corps Crew (PSCC) in knotweed survey and treatment. SFEG and WCC also received on-the-ground assistance in our efforts from several Skagit CWMA partners including: U.S. Forest Service, Seattle City Light and the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe. The Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe received a grant from the EPA in 2011 to do survey and treatment work on the Lower Sauk River and in the town of Darrington through 2013. This work was done in coordination with SFEG’s Upper Skagit Knotweed Control Project. The knotweed program met its goal of surveying and treating both the upper mainstem floodplains of the Sauk and Skagit Rivers. SFEG and WCC surveyed for knotweed from May through June and then implemented treatment from July until the first week of September. -

B.18: Skagit County Public Utilities District (PUD)

B.18: Skagit County Public Utilities District (PUD) www.skagitpud.org Skagit Public Utility District Number 1 (Skagit PUD) Resource conservation and stewardship are increasing concerns of the operates the largest water system in the county, PUD. Recognizing the value of water resources in Skagit County, the providing 9,000,000 gallons of piped water to PUD is a member of the Skagit Watershed Council and is actively approximately 70,000 people every day. The PUD participating in efforts to protect ins-stream flows. maintains nearly 600 miles of pipelines and has over 31,000,000 gallons of storage volume. The vision of the PUD - is to be recognized as an outstanding regional leader and innovative utility provider that embodies environmental Mount Vernon, Burlington, and Sedro-Woolley receive the majority of stewardship and sound economic practices. the PUD’s water. Due to public demand for quality water, the PUD also provides service to unincorporated and remote areas of the county. The mission of the PUD - is to provide quality, safe, reliable, and The District’s service area includes part of Fidalgo Island at the west affordable utility services to its customers in an environmentally- end of the county and extends as far east as Marblemount. From north responsible, collaborative manner. to south, the District’s service area starts in Conway and extends north to Alger/Lake Samish. The values of the PUD are: PUD water originates in the protected Cultus Mountain watershed area Quality east of Clear Lake from 4 streams. Melting snow and season rainfall Reliability are diverted from an uninhabited, 9 square mile, forested area, located Environmental responsibility high about the mountains. -

Structure and Petrology of the Deer Peaks Area Western North Cascades, Washington

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Winter 1986 Structure and Petrology of the Deer Peaks Area Western North Cascades, Washington Gregory Joseph Reller Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Reller, Gregory Joseph, "Structure and Petrology of the Deer Peaks Area Western North Cascades, Washington" (1986). WWU Graduate School Collection. 726. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/726 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STRUCTURE AMD PETROLOGY OF THE DEER PEAKS AREA iVESTERN NORTH CASCADES, WASHIMGTa^ by Gregory Joseph Re Her Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requiremerjts for the Degree Master of Science February, 1986 School Advisory Comiiattee STRUCTURE AiO PETROIDGY OF THE DEER PEAKS AREA WESTERN NORTIi CASCADES, VC'oHINGTON A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Western Washington University In Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Gregory Joseph Re Her February, 1986 ABSTRACT Dominant bedrock mits of the Deer Peaks area, nortliv/estern Washington, include the Shiaksan Metamorphic Suite, the Deer Peaks unit, the Chuckanut Fontation, the Oso volcanic rocks and the Granite Lake Stock. Rocks of the Shuksan Metainorphic Suite (SMS) exhibit a stratigraphy of meta-basalt, iron/manganese schist, and carbonaceous phyllite. Tne shear sense of stretching lineations in the SMS indicates that dioring high pressure metamorphism ttie subduction zone dipped to the northeast relative to the present position of the rocks. -

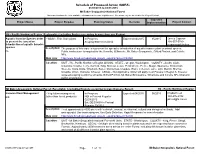

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 01/01/2015 to 03/31/2015 Mt Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact R6 - Pacific Northwest Region, Regionwide (excluding Projects occurring in more than one Region) Aquatic Invasive Species order - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants In Progress: Expected:04/2015 05/2015 James Capurso to prevent the spread or Scoping Start 05/05/2014 208-557-5780 introduction of aquatic invasive [email protected] species Description: The purpose of this order is to prevent the spread or introduction of aquatic invasive plant or animal species. CE Public involvement is targeted for the Umatilla, Willamette, Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie, Gifford Pinchot, and Colville NFs. Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/nepa/nepa_project_exp.php?project=44360 Location: UNIT - R6 - Pacific Northwest Region All Units. STATE - Oregon, Washington. COUNTY - Asotin, Clark, Columbia, Cowlitz, Ferry, Garfield, King, Klickitat, Lewis, Pend Oreille, Pierce, Skagit, Skamania, Snohomish, Stevens, Walla Walla, Whatcom, Baker, Clackamas, Douglas, Grant, Jefferson, Lane, Linn, Marion, Morrow, Umatilla, Union, Wallowa, Wheeler. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Order will apply to all Forests in Region 6, however targeted scoping is with the Umatilla, Gifford Pinchot, Mt. Baker/Snoqualmie, Willamette and Colville NFs tribal and public scoping lists. Mt Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest, Forestwide (excluding Projects occurring in more than one Forest) R6 - Pacific Northwest Region Invasive Plant Management - Vegetation management In Progress: Expected:04/2015 05/2015 Phyllis Reed EIS (other than forest products) NOI in Federal Register 360-436-2332 02/28/2012 [email protected] Est. -

Mt Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest EA CE

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2007 to 09/30/2007 Mt Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Aerial Application of Fire - Fuels management In Progress: Expected:08/2007 08/2007 Christopher Wehrli Retardant 215 Comment Period Legal 202-205-1332 EA Notice 07/28/2006 [email protected] Description: The Forest Service proposes to continue the aerial application of fire retardant to fight fires on National Forest System lands. An environmental analysis will be conducted to prepare an Environmental Assessment on the proposed action. Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/fire/retardant/index.html Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. Nation Wide. R6 - Pacific Northwest Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) Aquatic Outfitter and Guide - Special use management Developing Proposal Expected:08/2008 01/2009 Don Gay Special Use Permits Est. Scoping Start 11/2007 360-856-5700 CE [email protected] Description: Issuance of special use permits for outfitter and guides using the N.F. Nooksack, Skagit, Sauk, Skykomish, and Cispus Rivers. Location: UNIT - Mt Baker Ranger District, Darrington Ranger District, Skykomish Ranger District, Cowlitz Ranger District. STATE - Washington. COUNTY - Lewis, Skagit, Snohomish, Whatcom. LEGAL - T40NR6E, T39NR6 and 7E, T39NR7E, T35NR8,9,10E, T36NR11E, T31-35NR10E, T32NR9E, T27NR9 and 10E, T11NR5,6,7, and 8E. N. F. Nooksack, Skagit, Sauk, Skykomish, and Cispus Rivers. -

Yakama-Cowlitz Trail: Ancient and Modern Paths Across the Mountains

COLUMBIA THE MAGAZINE OF NORTHWEST HISTORY ■ SUMMER 2018 Yakama-Cowlitz Trail: Ancient and modern paths across the mountains North Cascades National Park celebrates 50 years • Explore WPA Legacies A quarterly publication of the Washington State Historical Society TWO CENTURIES OF GLASS 19 • JULY 14–DECEMBER 6, 2018 27 − Experience the beauty of transformed materials • − Explore innovative reuse from across WA − See dozens of unique objects created by upcycling, downcycling, recycling − Learn about enterprising makers in our region 18 – 1 • 8 • 9 WASHINGTON STATE HISTORY MUSEUM 1911 Pacific Avenue, Tacoma | 1-888-BE-THERE WashingtonHistory.org CONTENTS COLUMBIA The Magazine of Northwest History A quarterly publication of the VOLUME THIRTY-TWO, NUMBER TWO ■ Feliks Banel, Editor Theresa Cummins, Graphic Designer FOUNDING EDITOR COVER STORY John McClelland Jr. (1915–2010) ■ 4 The Yakama-Cowlitz Trail by Judy Bentley OFFICERS Judy Bentley searches the landscape, memories, old photos—and President: Larry Kopp, Tacoma occasionally, signage along the trail—to help tell the story of an Vice President: Ryan Pennington, Woodinville ancient footpath over the Cascades. Treasurer: Alex McGregor, Colfax Secretary/WSHS Director: Jennifer Kilmer EX OFFICIO TRUSTEES Jay Inslee, Governor Chris Reykdal, Superintendent of Public Instruction Kim Wyman, Secretary of State BOARD OF TRUSTEES Sally Barline, Lakewood Natalie Bowman, Tacoma Enrique Cerna, Seattle Senator Jeannie Darneille, Tacoma David Devine, Tacoma 14 Crown Jewel Wilderness of the North Cascades by Lauren Danner Suzie Dicks, Belfair Lauren14 Danner commemorates the 50th22 anniversary of one of John B. Dimmer, Tacoma Washington’s most special places in an excerpt from her book, Jim Garrison, Mount Vernon Representative Zack Hudgins, Tukwila Crown Jewel Wilderness: Creating North Cascades National Park. -

Structure and Petrology of the Grandy Ridge-Lake Shannon Area, North Cascades, Washington Moira T

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Winter 1986 Structure and Petrology of the Grandy Ridge-Lake Shannon Area, North Cascades, Washington Moira T. (Moira Tracey) Smith Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Moira T. (Moira Tracey), "Structure and Petrology of the Grandy Ridge-Lake Shannon Area, North Cascades, Washington" (1986). WWU Graduate School Collection. 721. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/721 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MASTER'S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master's degree at Western Washington University, I agree that the Library shall make its copies freely available for inspection. I further agree that extensive copying of this thesis is allowable only for scholarly purposes. It is understood, however, that any copying or publication of this thesis for commercial purposes, or for financial gain, shall not be allowed without my written permission . Bellin^hum, W'Mihington 9HZZS □ izoai aTG-3000 STRUCTURE AND PETROLOGY OF THE GRANDY RIDGE-LAKE SHANNON AREA, NORTH CASCADES, WASHINGTON By Moira T. Smith Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science aduate School ADVISORY COMMITEE: Chairperson MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non-exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU.