Getting to Yes: the Points of Light and Hands on Network Merger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frederick Thomas Bush

order, WHS collections; (14) WHS collections; (15) The Civil War by Ken Burns (website); (16)(17) WHS collections; (18) Report of Recruiting Committee, 1865 Town Report, 18; (19) 1889 Baptist church history, 14; (20) (21) WHS collec- tions; (22) WHS military enlistment lists; (23) Sears, 14; (24) Lamson, 140; (25) WHS collections, Alonzo Fiske to William Schouler, Adj. General of the Com- monwealth of Massachusetts, August 30, 1862; (26) WHS collections; Drake was one of Weston’s nine-months men; (27) (28) (29) (30) (31) WHS collections; (32) Sears, 7; (33) Hastings, “Re....Toplift” (sic), 1; (34) Sears, 11; (35) Faust, 85; (36) Encyclopedia of Death and Dying, Civil War, U.S (website); (37) Hastings, “Re....Rev. Toplift” (sic), 2; (38) Town Report Year ending March 31, 1864, 10; (39) Lamson, 143; (40) Letter courtesy Eloise Kenney, descendent of Stimpson; (41) Information provided by Eloise Kenney; (42) Faust, 236; (43) WHS collec- tions; (44) Report of the Selectmen, Town Report fort Year ending March 1863, 4 (45) Lamson, 140, and WHS collection handwritten “List of men drafted from the Town of Weston at Concord, July 18, 1863” containing 33 names; (46) Report of the Recruiting Committee, 19; (47) (48) WHS collections; (49 Lamson, 143; (50) (51) Report of the Recruiting Committee, 19-20. Weston’s China Trader: Frederick Thomas Bush By Isabella Jancourtz China trader and diplomat Frederick Thomas Bush (1815 – 1887) arrived in Weston in 1856 with his wife Elizabeth DeBlois and their five young children: Charles, Frederick, Amelia, Fannie, and Sophia. The young family had lived in China for nine years, and the three girls were born there. -

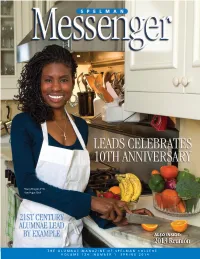

SPRING 2014 SPELMAN Messenger

Stacey Dougan, C’98, Raw Vegan Chef ALSO INSIDE: 2013 Reunion THE ALUMNAE MAGAZINE OF SPELMAN COLLEGE VOLUME 124 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2014 SPELMAN Messenger EDITOR All submissions should be sent to: Jo Moore Stewart Spelman Messenger Office of Alumnae Affairs ASSOCIATE EDITOR 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., Box 304 Joyce Davis Atlanta, GA 30314 COPY EDITOR OR Janet M. Barstow [email protected] Submission Deadlines: GRAPHIC DESIGNER Garon Hart Spring Semester: January 1 – May 31 Fall Semester: June 1 – December 31 ALUMNAE DATA MANAGER ALUMNAE NOTES Alyson Dorsey, C’2002 Alumnae Notes is dedicated to the following: EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE • Education Eloise A. Alexis, C’86 • Personal (birth of a child or marriage) Tomika DePriest, C’89 • Professional Kassandra Kimbriel Jolley Please include the date of the event in your Sharon E. Owens, C’76 submission. TAKE NOTE! WRITERS S.A. Reid Take Note! is dedicated to the following Lorraine Robertson alumnae achievements: TaRessa Stovall • Published Angela Brown Terrell • Appearing in films, television or on stage • Special awards, recognition and appointments PHOTOGRAPHERS Please include the date of the event in your J.D. Scott submission. Spelman Archives Julie Yarbrough, C’91 BOOK NOTES Book Notes is dedicated to alumnae authors. Please submit review copies. The Spelman Messenger is published twice a year IN MEMORIAM by Spelman College, 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., We honor our Spelman sisters. If you receive Atlanta, Georgia 30314-4399, free of charge notice of the death of a Spelman sister, please for alumnae, donors, trustees and friends of contact the Office of Alumnae Affairs at the College. -

September 11 & 12 . 2008

n e w y o r k c i t y s e p t e m b e r 11 & 12 . 2008 ServiceNation is a campaign for a new America; an America where citizens come together and take responsibility for the nation’s future. ServiceNation unites leaders from every sector of American society with hundreds of thousands of citizens in a national effort to call on the next President and Congress, leaders from all sectors, and our fellow Americans to create a new era of service and civic engagement in America, an era in which all Americans work together to try and solve our greatest and most persistent societal challenges. The ServiceNation Summit brings together 600 leaders of all ages and from every sector of American life—from universities and foundations, to businesses and government—to celebrate the power and potential of service, and to lay out a bold agenda for addressing society’s challenges through expanded opportunities for community and national service. 11:00-2:00 pm 9/11 DAY OF SERVICE Organized by myGoodDeed l o c a t i o n PS 124, 40 Division Street SEPTEMBER 11.2008 4:00-6:00 pm REGIstRATION l o c a t i o n Columbia University 9/11 DAY OF SERVICE 6:00-7:00 pm OUR ROLE, OUR VOICE, OUR SERVICE PRESIDENTIAL FORUM& 101 Young Leaders Building a Nation of Service l o c a t i o n Columbia University Usher Raymond, IV • RECORDING ARTIST, suMMIT YOUTH CHAIR 7:00-8:00 pm PRESIDEntIAL FORUM ON SERVICE Opening Program l o c a t i o n Columbia University Bill Novelli • CEO, AARP Laysha Ward • PRESIDENT, COMMUNITY RELATIONS AND TARGET FOUNDATION Lee Bollinger • PRESIDENT, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY Governor David A. -

Jean-Becker-KICD-Press-Release.Pdf

Kinder Institute on Constitutional Democracy announces distinguished MU alumna Jean Becker to serve on advisory board. Contact: Allison Smythe, 573.882.2124, smythea@missouri For more information on the Kinder Institute see democracy.missouri.edu COLUMBIA, Mo. – Today, the Kinder Institute on Constitutional Democracy at the University of Missouri announced that alumna Jean Becker, former chief of staff for George H. W. Bush, will serve on the institute’s advisory board, beginning July 1. “Jean Becker has had a remarkable career in journalism, government and public service,” said Justin Dyer, professor of political science and director of the Kinder Institute. “We look forward to working with her to advance the Kinder Institute’s mission of promoting teaching and scholarship on America’s founding principles and history.” Becker served as chief of staff for George H.W. Bush from March 1, 1994, until his death on Nov. 30, 2018. She supervised his office operations in both Houston, Texas, and Kennebunkport, Maine, overseeing such events as the opening of the George Bush Presidential Library Center in 1997, the commissioning of the USS George H.W. Bush aircraft carrier in January 2009, and coordinating special projects such as the Bush-Clinton Katrina Fund. She took a leave of absence in 1999 to edit and research All the Best, George Bush; My Life in Letters and Other Writings. Previously, Becker served as deputy press secretary to First Lady Barbara Bush from 1989 to 1992. After the 1992 election, she moved to Houston to help Mrs. Bush with the editing and research of her autobiography, Barbara Bush, A Memoir. -

Staying Connected Through Challenging Times

Ladies for Literacy Guild Newsletter - Summer 2020 Staying Connected Through Challenging Times Dear Ladies Guild Members and Friends, I have been thinking a lot about the word “connection” as it relates to these unusual times and, like many of you, missing the connection of familiar routines. My late father was a Special Forces Green Beret who served three tours of duty in Vietnam. A POW, he came back from his last service a very different man than the one that left Fort Bragg on his first tour. Many years later when I was a teenager, my dad was able to share his experiences with me and what he clung to during those dark, dark days. It was, in short, connections to us that, despite the span of continents, kept us close. Along with sending Polaroids and long letters, my mother recorded me reading my favorite childhood books to share with my dad. Decades later, he told me that hearing the voices of his three girls gave him the strength and hope he needed more than any other time in his life. As we hope and pray for a brighter tomorrow, I am reminded that we have had tough days – yet we have survived them all. With resilience, grit, determination and creative focus, we have and will continue to look for a tomorrow where we can all feel safe to gather again, volunteer in our beloved schools and work in the community to advance the cause of literacy. Until that time, I remain inspired by the optimism and creativity by our Guild members. -

U.S. Postal Service Honoring Former President George H.W. Bush With

National: Roy Betts FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 202.268.3207 May 23, 2019 [email protected] Local: Kanickewa “Nikki” Johnson 832.221.7514 [email protected] U.S. Postal Service Honoring Former President George H.W. Bush with Forever Stamp First Day of Issue Event June 12th at Bush Center in College Station, Acknowledging President Bush 95th Birthday What: The U.S. Postal Service is issuing a Forever stamp honoring George Herbert Walker Bush, America’s 41st president, who died on November 30, 2018. The first day of issue event for the stamps is free and open to the public. News of the stamp is being shared with the hashtags #GHWBushStamp or #USPresidentsStamps. Who: Pierce Bush, CEO, Big Brothers Big Sisters Lone Star, Grandson of George H.W. Bush Hon. Robert M. Duncan, Chairman, Board of Governors, U.S. Postal Service, and Dedicating Official David B. Jones, President and CEO, George & Barbara Bush Foundation Warren Finch, Director, George H.W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum Amb. Chase Untermeyer, Founding Chairman, Qatar-America Institute Jean Becker, Former Chief of Staff, Office of George H.W. Bush When: Wednesday, June 12, 2019, at 11 a.m. CDT Where: Annenberg Presidential Conference Center Frymire Auditorium 1002 George Bush Drive West College Station, TX 77845 RSVP: Dedication ceremony attendees are encouraged to RSVP at usps.com/georgehwbush. Background: George Herbert Walker Bush (1924–2018), served as America’s 41st president from 1989 to 1993. During his term in office, he guided the U.S. and its allies to a peaceful end of the Cold War, helped reunify Germany, and led a multinational coalition that successfully forced Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait during the Persian Gulf War. -

District Policy Group Provides Top-Line Outcomes and Insight, with Emphasis on Health Care Policy and Appropriations, Regarding Tuesday’S Midterm Elections

District Policy Group provides top-line outcomes and insight, with emphasis on health care policy and appropriations, regarding Tuesday’s midterm elections. Election Outcome and Impact on Outlook for 114th Congress: With the conclusion of Tuesday’s midterm elections, we have officially entered that Lame Duck period of time between the end of one Congress and the start of another. Yesterday’s results brought with them outcomes that were both surprising and those that were long-anticipated. For the next two years, the House and Senate will be controlled by the Republicans. However, regardless of the predictions that pundits made, the votes are in, Members of the 114th Congress (2015-2016) have been determined, and we can now begin to speculate about what these changes will mean for business interests and advocacy organizations. Even though we now have a Republican majority in Congress, for the next two years, President Obama remains resident at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Although President Obama will be a Lame Duck President, he still has issues and priority policies he wishes to pursue. Many other Lame Duck presidents have faced Congresses controlled by the opposite party and how a President responds to the challenge often can determine his legacy. Given the total number of Republican pick-ups in the House and Senate, we anticipate the GOP will feel emboldened to pursue its top policy priorities; as such, we do not suspect that collaboration and bipartisanship will suddenly arrive at the Capitol. We anticipate the Democrats will work hard to try to keep their caucus together, but this may prove challenging for Senate Minority Leader Reid, especially with the moderate Democrats and Independents possibly deciding to ally with the GOP. -

Metaphors in Politics a Study of the Metaphorical Personification of America in Political Discource

2007:080 C EXTENDED ESSAY Metaphors in Politics A study of the metaphorical personification of America in political discource IDA VESTERMARK Luleå University of Technology Department of Languages and Culture ENGLISH C Supervisor: Marie Nordlund 2007:080 • ISSN: 1402 - 1773 • ISRN: LTU - CUPP--07/80 - - SE C-EXTENDED ESSAY Metaphors in politics A study of the metaphorical personification of America in political discourse Ida Vestermark Luleå University of Technology Department of Languages and Culture English C Supervisor: Marie Nordlund Abstract The language of politics is a complex issue which includes many strategies of language use to influence the receiver toward a desired attitude or thought. Depending on the aim and conviction of the speaker, the use of language strategies differs. The topic of this essay is metaphors in politics and more specifically the personification of America in the first inaugural addresses by Ronald Reagan, George H W Bush, Bill Clinton and George W Bush. The focus is on how the metaphors are used, how they can be interpreted and what message they send to the receiver. This essay will argue that the conceptual metaphors used in political discourse in the inaugurals are highly intentional, but not always as easy to detect. The rhetorical strategy of conceptualizing America as human is analyzed and the conceptual metaphors accounted for and analyzed are THE WORLD AS A COMMUNITY , NATION AS A PERSON , NATION WITH HUMAN ATTRIBUTES and NATION ACTING AS HUMAN . The conclusion drawn is that the four presidents included all frequently use metaphors to personify the nation with the aim to make the American people identify with and understand their beliefs and goals for America. -

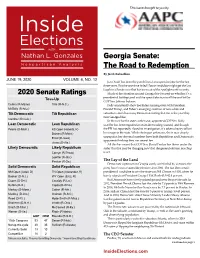

June 19, 2020 Volume 4, No

This issue brought to you by Georgia Senate: The Road to Redemption By Jacob Rubashkin JUNE 19, 2020 VOLUME 4, NO. 12 Jon Ossoff has been the punchline of an expensive joke for the last three years. But the one-time failed House candidate might get the last laugh in a Senate race that has been out of the spotlight until recently. 2020 Senate Ratings Much of the attention around Georgia has focused on whether it’s a Toss-Up presidential battleground and the special election to fill the seat left by GOP Sen. Johnny Isakson. Collins (R-Maine) Tillis (R-N.C.) Polls consistently show Joe Biden running even with President McSally (R-Ariz.) Donald Trump, and Biden’s emerging coalition of non-white and Tilt Democratic Tilt Republican suburban voters has many Democrats feeling that this is the year they turn Georgia blue. Gardner (R-Colo.) In the race for the state’s other seat, appointed-GOP Sen. Kelly Lean Democratic Lean Republican Loeffler has been engulfed in an insider trading scandal, and though Peters (D-Mich.) KS Open (Roberts, R) the FBI has reportedly closed its investigation, it’s taken a heavy toll on Daines (R-Mont.) her image in the state. While she began unknown, she is now deeply Ernst (R-Iowa) unpopular; her abysmal numbers have both Republican and Democratic opponents thinking they can unseat her. Jones (D-Ala.) All this has meant that GOP Sen. David Perdue has flown under the Likely Democratic Likely Republican radar. But that may be changing now that the general election matchup Cornyn (R-Texas) is set. -

George H.W. Bush, "Speech at Penn State University" (23 September 1992)

Voices of Democracy 2 (2007): 126‐151 Hogan & Mehltretter 126 GEORGE H.W. BUSH, "SPEECH AT PENN STATE UNIVERSITY" (23 SEPTEMBER 1992) J. Michael Hogan and Sara Ann Mehltretter Pennsylvania State University Abstract: During the 1992 presidential campaign, President George H. W. Bush lost a lead in the polls and subsequently the presidency to Bill Clinton. This study helps to account for that loss by illuminating weaknesses in his campaign stump speech. Bush's speech at Penn State University reflected his difficulties in distinguishing himself from his challenger and articulating a vision for his second term. The essay also illustrates larger controversies over politics and free speech on campus. Key Words: 1992 presidential election, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, campaign speeches, free speech on campus, Penn State University On September 23, 1992, President George H.W. Bush brought his reelection campaign to the University Park campus of the Pennsylvania State University. Speaking on the steps of Old Main to a cheering crowd of supporters, Bush said little new in the speech. Yet it still proved controversial, not so much because of what Bush said, but because of the way the event was staged. Sparking controversy over the distribution of tickets and the treatment of protestors at the event, Bush's appearance dramatized the difficulties of staging campaign events at colleges and universities. It also raised larger issues about politics and free speech on campus. Bush's speech at Penn State was carefully prepared and vetted by his speech‐ writing staff and White House advisers. Yet despite all the effort that went into the speech, it was vague, uninspired, and unresponsive to criticisms of his administration, reflecting the larger problems with Bush's faltering campaign. -

REPORT 2019 at POINTS of LIGHT, We Believe That the Most Powerful Force of Change in Our World Is the Individual — One Who Makes a Positive Difference

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 AT POINTS OF LIGHT, we believe that the most powerful force of change in our world is the individual — one who makes a positive difference. We are a nonpartisan organization that inspires, equips and connects nonprofits, businesses and individuals ready to apply their time, talent, voice and resources to solve society’s greatest challenges. And we believe every action, no matter how small, can have an impact and change a life. Points of Light is committed to empowering, connecting and engaging people and organizations with opportunities to make a difference that are personal and meaningful. With our global network, we partner with corporations to help them become leaders in addressing challenges and encouraging deeper civic engagement that our society needs. Together, we are a force that transforms the world. O Z A T I N S B U S I N I N E A S S G E R S O T C 173 A Global Network 262 P Affiliates Businesses Engaged M I Per Year 37 41 L Countries U.S. States A I 57,000 C Local Community O Partners 3 million S Employees Mobilized Through Business Partners Per Year OUR GLOBAL 2 million People Engaged IMPACT Per Year Points of Light is committed to empowering, connecting and engaging people and organizations 1.9 million with opportunities to make a President’s Volunteer 6,500+ Service Awards difference that are meaningful and Daily Point impactful. Together with our Points of Light Awards of Light Global Network, we partner with social impact organizations, businesses and individuals to create 1,300+ UK and Commonwealth a global culture of volunteerism and Point of civic engagement. -

Newsbreak ELECTIONS MATTER ELECTIONS MATTER

NEWSbreak ELECTIONS MATTER NEWSbreak ELECTIONS MATTER Vital News and Research Information for JAC Membership July-August 2014 Presidential Outlook YY Israel & the Middle East At what point do we After another weekend of intense fighting, tunnels from Gaza to Israel have been decide that enough discovered and destroyed, casualties have mounted, and Israel has lost many is enough? Recent brave soldiers. “In battle there are casualties, but our role is to fulfill missions –- news concerning and we will continue in that,” said Lt. Gen. Gantz. To the “misfortune of Gaza’s the Hobby Lobby residents,” Gantz said, Hamas “instead of building houses, schools, hospitals and decision by the factories,” had built a war machine in residential areas. (Times of israel 7/21/14) Supreme Court is on the radar screens of President Obama again reaffirmed the strong relationship between the United Janna Berk even my most “non- States and Israel, emphatically stressing Israel’s right to defend its citizens political” friends, from Hamas’s rockets. On July 18th, President Obama said, “I spoke with PM raising questions in my mind as to what it really takes to move people to action. I’ve Netanyahu of Israel about the situation in Gaza. I reaffirmed my strong support heard true disgust expressed at the thought ISRAEL continued on page 2 of an employer being able to decide, based on his/her religious beliefs, that employees Reproductive Rights will be denied insurance coverage for Women’s reproductive choice was delivered a huge blow by the Supreme Court birth control. But the discussions are more this month in two suits, brought by anti-choice advocates, and attacked choice compelling because of the finality of the from different sides.