The Framing of Webster's the Duchess of Malfi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The RSC Duchess of Malfi

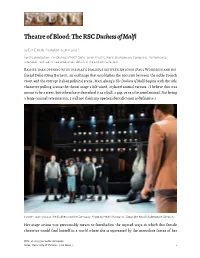

Theatre of Blood: The RSC Duchess of Malfi by Erin E. Kelly. Published in 2018 Issue 1. For the production: The Duchess of Malfi (2018, Swan Theatre, Royal Shakespeare Company). Performance attended: 2018-04-11. See production details at the end of the review. RATHER THAN OPENING WITH THE PLAY’S DIALOGUE BETWEEN ANTONIO (PAUL WOODSON) AND HIS friend Delio (Greg Barnett), an exchange that establishes the contrast between the noble French court and the corrupt Italian political scene, Mari Aberg’s The Duchess of Malfi begins with the title character pulling across the thrust stage a life-sized, stylized animal carcass. (I believe this was meant to be a steer, but others have described it as a bull, a pig, or as a fictional animal. Not being a large-animal veterinarian, I will not claim my species identification is definitive.) Figure 1. Joan Iyiola as The Duchess and the Company. Photo by Helen Maybanks. Copyright Royal Shakespeare Company. Her stage action was presumably meant to foreshadow the myriad ways in which this female character would find herself in a world where she is oppressed by the masculine forces of her DOI: 10.18357/sremd01201819086 Scene. University of Victoria. 2018 Issue 1. 1 Swan Theatre–—Duchess of Malfi Erin E. Kelly dead first husband, her scheming brothers, and the patriarchy’s standards for feminine virtue. By the production’s end, however, I wondered whether we had more accurately been signaled that all involved in the production—including the audience—would be weighed down by unnecessary difficulties. Figure 2. Joan Iyiola as The Duchess. -

The Duchess of Malfi Announced

Press release: Thursday 12 September The Almeida Theatre announces Associate Director Rebecca Frecknall’s new production of John Webster’s revenge tragedy The Duchess of Malfi, with Lydia Wilson in the title role. The production opens on Tuesday 10 December 2019, with previews from Monday 2 December, and runs until Saturday 18 January 2020. It follows Frecknall’s previously acclaimed Almeida productions of Three Sisters and the Olivier Award-winning Summer and Smoke. THE DUCHESS OF MALFI by John Webster Direction: Rebecca Frecknall; Design: Chloe Lamford; Costume: Nicky Gillibrand; Light: Jack Knowles; Sound: George Dennis Cast includes: Lydia Wilson. Monday 2 December 2019 – Saturday 18 January 2020 Press night: Tuesday 10 December 7pm “Whether we fall by ambition, blood or lust Like diamonds, we are cut with our own dust” You fall in love. You get married. You have children. You live happily ever after. Almeida Associate Director Rebecca Frecknall follows her Olivier Award-winning production of Summer and Smoke and Three Sisters with The Duchess of Malfi, John Webster’s electrifying revenge tragedy about rage, resistance and a deadly lust for power. John Webster (1580 – 1634) was an English dramatist and contemporary of William Shakespeare, best known for his tragedies The White Devil and The Duchess of Malfi. Rebecca Frecknall is Associate Director at the Almeida Theatre. For the Almeida, she has directed Three Sisters, Summer and Smoke (also West End and winner of two Olivier Awards including Best Revival) and worked as Associate Director on Ink at the Almeida/Duke of York’s Theatre and Movement Director on Albion. -

Italian Perspectives on Late Tudor and Early Stuart Theatre

Early Theatre 8.2 Issues in Review Richard Allen Cave Italian Perspectives on Late Tudor and Early Stuart Theatre The general focus of art exhibitions in Italy has changed significantly in recent years; the objective of this essay is to outline how such a change holds considerable value for the historian of early modern theatre and demonstrates innovative potential for the dissemination of theatre scholarship. Nowadays galleries offer fewer blockbuster retrospectives of the collected works of the painters who constitute the canon; such retrospectives were designed to be seen in a calculated isolation so that viewers might contemplate aesthetic issues concerning ‘development’. This style of exhibition now tends to travel to London, Washington, Boston, Tokyo, so that masterpieces now in the collec- tions of major international galleries may be seen in relation to less familiar work from the ‘source’ country (chiefly, one suspects, to have that status of masterpiece substantiated and celebrated). An older style of exhibition in Italy, which centred less on the individual painter and more on genres, has returned but in a markedly new guise. Most art forms in the early modern period were dependent on patronage, initially the Church, subsequently as an expression of princely magnificence. Some Italian artists were associated with a particular dynasty and its palaces; others were sought after, seduced to travel and carry innovation with them into new settings. The new style of exhibition celebrates dynastic heritage: the Gonzaga at Mantua (2002); Lucrezia Borgia’s circle at Ferrara (2002); le delle Rovere at Urbino, Pesaro, Senigallia, Urbania (2004). As is indicated by this last exhibition, the sites have shifted from traditional galleries into the places where each dynasty flourished, often as in the case of the delle Rovere being held in a variety of palatial homes favoured by the family 109 110 Richard Allen Cave as their seats of power and of leisure. -

Diprose's Theatrical Anecdotes

^ :> Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/diprosestheatricOOdipruoft ^DIP ROSE'S theatrical anecdotes' CONTAINING ANECDOTES OF THE SCENES-OLD iIIE STAGE AND THE PLAYERS-BEHIND PLACES OF AMUSEMENT-THEATRICAL JOTTINGS- == MUSIC-AUTHORS-EPITAPHS, &c., &c. London : DIPROSE & BATEMAN, Sheffield Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields. : LONDON DIPROSE, BATEMAN AND CO., PRINTEUS, SHEFFIELD STREET, LINCOLN'S INN, THE STAGE I AND THE PLAYERS BY JOHN DIPROSE. ^ THE ORIGIN OF THE STAGE. -:o:- HE first religious spectacle was, probably, the miracle play of St Catherine^ mentioned by Matthew Paris as having been written by Geoffrey, a Norman, afterwards Abbot of St. Albans, and played at Dunstable Abbey in mo. In the Description of the Most Noble City of London^ by Fitz Stephen, a monk, about 1174, in treating of the ordinary diversions of the inhabitants of the metropolis, says, that, instead of the common interludes belonging to theatres, they have plays of a more holy subject. The ancient religious dramas were distinguished by the names Origin of the Stage. of mysteries, properly so called, wherein were exhibited some of the events of Scripture story, and miracles which were of the nature of tragedy, representing the acts of Martyrdom of a Saint of the Church. One of the oldest religious dramas was written by Gregory, entitled Christ's Passion, the prologue to which states that the Virgin Mary was then for the first time brought upon the stage. In 1264, the Fraternite del Goufal'one Avas established, part of whose occupation was to represent the sufferings of Christ in Passion Week. -

Evan Gaughan

Introduction The aim of this thesis is to reassess the role of women as significant collectors and patrons of natural history, fine arts and antiquities in the long eighteenth century.1 The agency and achievements of early modern female collectors and patrons have been largely eclipsed by histories of gentlemen virtuosi and connoisseurs, which examine patriarchal displays of collecting and patronage while overlooking and undervaluing the contributions made by their female counterparts. These works, in general, have operated within an androcentric framework and dismissed or failed to address the ways in which objects were commissioned, accumulated, or valued by those who do not fit into prevailing male-dominated narratives. Only in the last decade have certain scholars begun to take issue with this historiographical ignorance and investigated the existence and importance of a corresponding culture of collecting and patronage in which women exercised considerable authority. Most of this literature consists of limited, superficial portrayals that do not tell us much about the realities of female collecting and patronage in any given time or place. This project attempts to fill the historiographical gap through a detailed study of several of the most prominent British female collectors and patrons of the long eighteenth century and an analysis of how their experiences and activities disrupt or complicate our understanding of contemporary collecting and patronage practices. Although a significant intention of this thesis is to reveal the lack of well-focused or sustained scholarship on this topic, its primary objective is to restore women to their central place in the history of 1 For the purposes of this thesis, the eighteenth century has been expanded to embrace related historical movements that occurred in the first two and a half decades of the nineteenth century. -

Duchess of Malfi, the White Devil, the Broken Heart and Tis Pity Shes a Whore Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DUCHESS OF MALFI, THE WHITE DEVIL, THE BROKEN HEART AND TIS PITY SHES A WHORE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Revd Prof. John Webster,John Ford,Jane Kingsley-Smith | 640 pages | 29 Sep 2015 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141392233 | English | London, United Kingdom Duchess of Malfi, the White Devil, the Broken Heart and Tis Pity Shes a Whore PDF Book And we should be thankful to Ben Jonson for writing poetry such as this. Add to cart. In The Broken Heart , John Ford questions the value of emotional repression as his characters attempt to subdue their desires and hatreds in ancient Greece. Heart of Darkness Joseph Conrad. Together with the Penguin volume of Five Revenge Tragedies , edited by Emma Smith, this is the essential sourcebook for drama in the period. Are you happy to accept all cookies? Essential We use cookies to provide our services , for example, to keep track of items stored in your shopping basket, prevent fraudulent activity, improve the security of our services, keep track of your specific preferences e. Bookishjq rated it it was amazing Jun 01, Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons. Cancel Submit. Sign in to Purchase Instantly. Learn about new offers and get more deals by joining our newsletter. Discourses and Selected Writings Epictetus. Your subscription to Read More was successful. Product Details About the Author. Mikhail Bulgakov. Tragedies, vol. How was your experience with this page? You can learn more about how we plus approved third parties use cookies and how to change your settings by visiting the Cookies notice. These four plays, written during the reigns of James I and Charles I, took revenge tragedy in dark and ambiguous new directions. -

CYMBELINE" in the Fllii^Slhi TI CENTURY

"CYMBELINE" IN THE fllii^SLHi TI CENTURY Bennett Jackson Submitted in partial fulfilment for the de ree of uaster of Arts in the University of Birmingham. October 1971. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. SYNOPSIS This thesis consists of an Introduction, followed by Part I (chapters 1-2) in which nineteenth- century criticism of the play is discussed, particular attention being paid to Helen Faucit's essay on Imogen, and its relationship to her playing of the role. In Part II the stags-history of Oymbcline in London is traced from 1785 to Irving's Lyceum production of 1896. Directions from promptbooks used by G-.P. Cooke, W.C. Macready, Helen Eaucit, and Samuel ±helps are transcribed and discussed, and in the last chapter the influence of Bernard Shaw on Ellen Terry's Imogen is considered in the light of their correspondence and the actress's rehearsal copies of the play. There are three appendices: a list of performances; transcriptions of two newspaper reviews (from 1843 and 1864) and one private diary (Gordon Crosse's notes on the Lyceum Gymbeline); and discussion of one of the promptbooks prepared for Charles Kean's projected production. -

Consignors' Index

Consignors’ Index Hip Color No. and Sex Sire Dam 4M RANCH, AGENT—Barn 13 824 ch.c. ..............Real Solution ...........................................Stormy Sister 1407 dkb/b.f. .........Bal a Bali (BRZ) ......................................Desert Fantasy (GB) 4M RANCH, AGENT II—Barn 13 129 dkb/b.c. .........Bind ........................................................Ideratherblucky 147 ch.f. ...............Aikenite ...................................................In Step Dancer 4M RANCH, AGENT III—Barn 13 575 ch.f. ...............Lookin At Lucky .....................................Queen Cleopatra ANDERSON FARMS, AGENT—Barn 3 363 gr/ro.f. ...........Frosted ....................................................Miss Emilia 498 b.c. ................Quality Road ...........................................Pearl Turn 505 dkb/b.f. .........Hard Spun ..............................................Pengally Bay 609 b.c. ................Nyquist ...................................................Reason 1537 b.c. ................Hard Spun ..............................................Fragrance BACCARI BLOODSTOCK LLC, AGENT I—Barn 3 863 b.f..................Constitution ............................................Sweet Problem 996 b.c. ................Mastery ...................................................Veronique 1092 b.c. ................Union Rags .............................................After ought 1132 b.c. ................Medaglia d’Oro .......................................Appealing Bride 1345 ch.c. ..............Classic Empire -

Early Modern Culture and Literature: Renaissance Drama

Carleton University Fall 2012 Department of English Language and Literature ENGL 4304A Renaissance Drama Thurs. 11:35-2:25 (Please confirm location on Carleton Central) Instructor: Dr. David Stymeist Office: 1819 DT Office Phone: TBA Email: [email protected] Office Hours: TBA, or by appointment. Course Description This course is designed to examine of a selection of drama from the English Renaissance. This course will include work by Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Dekker, William Shakespeare, John Webster, Francis Beaumont, and John Ford. These plays will encompass the major dramatic genres of History, Comedy, and Tragedy, as well as a number of sub-genres, such as City Comedy, Satire, Domestic Tragedy, and the Revenge play. The cultural, political and intellectual contexts of individual plays will be discussed in detail, as well as the social and economic place of the stage in early modern England. There will be an emphasis on the commercial development of drama in the period. The course will also investigate how playwrights represent transgression, femininity, homosexuality, social and economic class differences, and criminality in the period. The practice of drama in the period will be examined through various critical and theoretical methodologies, including Feminist historiography, Queer theory, Cultural Materialism, and New Historicism. Classes will consist of a combination of lectures and discussion. I expect every student to attend lectures and come prepared to engage in a lively discussion of the plays. As this is a fourth year course, classes will especially emphasize active learning. The more you are willing to put into the class, the more you will get out of it! Primary Texts Anonymous. -

Gesture and Movement in Silent Shakespeare Films

Gesticulated Shakespeare: Gesture and Movement in Silent Shakespeare Films Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Rebecca Collins, B.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Alan Woods, Advisor Janet Parrott Copyright by Jennifer Rebecca Collins 2011 Abstract The purpose of this study is to dissect the gesticulation used in the films made during the silent era that were adaptations of William Shakespeare's plays. In particular, this study investigates the use of nineteenth and twentieth century established gesture in the Shakespearean film adaptations from 1899-1922. The gestures described and illustrated by published gesture manuals are juxtaposed with at least one leading actor from each film. The research involves films from the experimental phase (1899-1907), the transitional phase (1908-1913), and the feature film phase (1912-1922). Specifically, the films are: King John (1899), Le Duel d'Hamlet (1900), La Diable et la Statue (1901), Duel Scene from Macbeth (1905), The Taming of the Shrew (1908), The Tempest (1908), A Midsummer Night's Dream (1909), Il Mercante di Venezia (1910), Re Lear (1910), Romeo Turns Bandit (1910), Twelfth Night (1910), A Winter's Tale (1910), Desdemona (1911), Richard III (1911), The Life and Death of King Richard III (1912), Romeo e Giulietta (1912), Cymbeline (1913), Hamlet (1913), King Lear (1916), Hamlet: Drama of Vengeance (1920), and Othello (1922). The gestures used by actors in the films are compared with Gilbert Austin's Chironomia or A Treatise on Rhetorical Delivery (1806), Henry Siddons' Practical Illustrations of Rhetorical Gesture and Action; Adapted to The English Drama: From a Work on the Subject by M. -

2019 Seminar Abstracts: the King's Men and Their Playwrights

1 2019 Seminar Abstracts: The King’s Men and Their Playwrights Meghan C. Andrews, Lycoming College James J. Marino, Cleveland State University “Astonishing Presence”: Writing for a Boy Actress of the King’s Men, c. 1610-1616 Roberta Barker, Dalhousie University Although scholarship has acknowledged the influence of leading actors such as Richard Burbage on the plays created for the King’s Men, less attention has been paid to the ways in which the gifts and limitations of individual boy actors may have affected the company’s playwrights. Thanks to the work of scholars such as David Kathman and Martin Wiggins, however, it is now more feasible than ever to identify the periods during which specific boys served their apprenticeships with the company and the plays in which they likely performed. Building on that scholarship, my paper will focus on the repertoire of Richard Robinson (c.1597-1648) during his reign as one of the King’s Men’s leading actors of female roles. Surviving evidence shows that Robinson played the Lady in Middleton’s Second Maiden’s Tragedy in 1611 and that he appeared in Jonson’s Catiline (1611) and Fletcher’s Bonduca (c.1612-14). Using a methodology first envisioned in 1699, when one of the interlocutors in James Wright’s Historia Histrionica dreamt of reconstructing the acting of pre-Civil War London by “gues[sing] at the action of the Men, by the Parts which we now read in the Old Plays” (3), I work from this evidence to suggest that Robinson excelled in the roles of nobly born, defiant tragic heroines: women of “astonishing presence,” as Helvetius says of the Lady in The Second Maiden’s Tragedy (2.1.74). -

"A Sharers' Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical

Syme, Holger Schott. "A Sharers’ Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical Documents in Shakespeare’s England. Ed. Tiffany Stern. London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2020. 33–51. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350051379.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 08:28 UTC. Copyright © Tiffany Stern and contributors 2020. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 2 A Sharers’ Repertory Holger Schott Syme Without Philip Henslowe, we would know next to nothing about the kinds of repertories early modern London’s resident theatre companies offered to their audiences. As things stand, thanks to the existence of the manuscript commonly known as Henslowe’s Diary , scholars have been able to contemplate the long lists of receipts and expenses that record the titles of well over 200 plays, most of them now lost. The Diary gives us some sense of the richness and diversity of this repertory, of the rapid turnover of plays, and of the kinds of investments theatre companies made to mount new shows. It also names a plethora of actors and other professionals associated with the troupes at the Rose. But, because the records are a fi nancier’s and theatre owner’s, not those of a sharer in an acting company, they do not document how a group of actors decided which plays to stage, how they chose to alternate successful shows, or what they, as actors, were looking for in new commissions.