Shawn Earle DMA Thesis Final Revision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pierre Trudeau Prime Minister

PIERRE TRUDEAU PRIME MINISTER Joseph Philippe Pierre Yves Elliott Trudeau PC CC CH QC .. Prime Ministers all : (l-r) Trudeau, future leaders John Turner and Jean Chrétien, and Trudeau's predecessor, Lester B. The Liberals won mostly on the strength of a solid performance in the eastern half of the country. His energetic campaign attracted massive media attention and mobilized many young people, who saw Trudeau as a symbol of generational change. His father was a French-Canadian businessman, His mother was of Scottish ancestry, and although bilingual, spoke English at home. He defeated several prominent and long-serving Liberals including Paul Martin Sr. He immediately called an election. For information about the 28th Parliament, to , see 28th Canadian Parliament. Ignatieff resigned as party leader immediately after the election, and rumours again circulated that Trudeau could run to become his successor. Over a five-week period he attended many lectures and became a follower of personalism after being influenced most notably by Emmanuel Mounier. In this and other forums, Trudeau sought to rouse opposition to what he believed were reactionary and inward-looking elites. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us! In his next election, in at the height of Trudeaumania , he received Trudeau, in an attempt to represent Western interests, offered to form a coalition government with Ed Broadbent's NDP, which had won 22 seats in the west, but was rebuffed by Broadbent out of fear the party would have no influence in a majority government. Trudeau criticized the Liberal Party of Lester Pearson when it supported arming Bomarc missiles in Canada with nuclear warheads. -

From Britishness to Multiculturalism: Official Canadian Identity in the 1960S

Études canadiennes / Canadian Studies Revue interdisciplinaire des études canadiennes en France 84 | 2018 Le Canada et ses définitions de 1867 à 2017 : valeurs, pratiques et représentations (volume 2) From Britishness to Multiculturalism: Official Canadian Identity in the 1960s De la britannicité au multiculturalisme : l’identité officielle du Canada dans les années 1960 Shannon Conway Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/eccs/1118 DOI: 10.4000/eccs.1118 ISSN: 2429-4667 Publisher Association française des études canadiennes (AFEC) Printed version Date of publication: 30 June 2018 Number of pages: 9-30 ISSN: 0153-1700 Electronic reference Shannon Conway, « From Britishness to Multiculturalism: Official Canadian Identity in the 1960s », Études canadiennes / Canadian Studies [Online], 84 | 2018, Online since 01 June 2019, connection on 07 July 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/eccs/1118 ; DOI : 10.4000/eccs.1118 AFEC From Britishness to Multiculturalism: Official Canadian Identity in the 1960s Shannon CONWAY University of Ottawa The 1960s was a tumultuous period that resulted in the reshaping of official Canadian identity from a predominately British-based identity to one that reflected Canada’s diversity. The change in constructions of official Canadian identity was due to pressures from an ongoing dialogue in Canadian society that reflected the larger geo-political shifts taking place during the period. This dialogue helped shape the political discussion, from one focused on maintaining an out-dated national identity to one that was more representative of how many Canadians understood Canada to be. This change in political opinion accordingly transformed the official identity of the nation-state of Canada. Les années 1960 ont été une période tumultueuse qui a fait passer l'identité officielle canadienne d'une identité essentiellement britannique à une identité reflétant la diversité du Canada. -

Indigenous People and Parliament P. 24 Moving Forward Together

Canadian eview V olume 39, No. 2 Moving Forward Together: Indigenous People and Parliament p. 24 The Mace currently in use in the Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan was made in 1906 and used for the first time in March of that year at the opening of the First Session of the First Legislative Assembly. Purchased from Ryrie Bros. Ltd. of Toronto at a cost of $340.00, it is made of heavy gold-plated brass and is about four feet long. The head consists of a Royal Crown with the arches surmounted by a Maltese cross and bears the Royal Coat-of-Arms on the top indicating the Royal Authority. Each side is decorated with a sheaf of wheat, representing the province’s agricultural wealth, a beaver representing Canada and the monogram E.R. VII, representing the sovereign at the time, Edward VII. The shaft and base are ornamented with a shamrock, thistle and rose intertwined. A Latin inscription around the Royal Coat of Arms reads in English, “Edward the Seventh, by the Grace of God of British Isles and Lands beyond the sea which are under British rule, King, Defender of the Faith, Emperor of India”. Monique Lovett Manager of Interparliamentary Relations and Protocol Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan Courtesy of British Columbia Legislative Library Stick Talking BC Legislature, The Canadian Parliamentary Review was founded in 1978 to inform Canadian legislators about activities of the federal, provincial and territorial branches of the Canadian Region of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association and to promote the study of and interest in Canadian parliamentary institutions. -

Symposium Speakers Short Bios

SYMPOSIUM SPEAKERS SHORT BIOS James BEZAN Member of Parliament for SELKIRK-INTERLAKE, Canada Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of National Defence, Canada Mr. Bezan was raised on a farm near Inglis, Manitoba and is a graduate of Olds College in Alberta. Mr. Bezan and his wife Kelly have three daughters; Cortney, Taylor, and Cassidy, and live on a farm by Teulon, Manitoba. Mr. Bezan is a member of the Teulon and District Lions Club and his family is active in their church. In addition to being a cattle producer, Mr. Bezan has held various positions in agri- businesses, as well as owning an export and consulting company. On June 28th, 2004, Mr. Bezan was first elected to the House of Commons in the 38th Parliament as a Conservative Member of Parliament to represent the riding of Selkirk- Interlake. During his time in Opposition, Mr. Bezan held the positions of Associate Agriculture Critic and Executive Member of the Canada-Europe Parliamentary Association. With the support of his constituents, Mr. Bezan was re-elected on January 23rd, 2006, October 14, 2008 and on May 2, 2011 to represent Selkirk-Interlake for four consecutive terms. Mr. Bezan is proud to be a member of the Conservative Government lead by Prime Minister Stephen Harper. As a member of government Mr. Bezan has served as Chair of the Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food; Chair of the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development; Chair of the Manitoba Conservative Caucus; Chair of the Canadian Section of the Inter-Parliamentary Forum of the Americas (FIPA); and Secretary of the Canada-Ukraine Parliamentary Friendship Group. -

To Play Jewish Again: Roots, Counterculture, and the Klezmer Revival Claire Marissa Gogan Thesis Submitted to the Faculty Of

To Play Jewish Again: Roots, Counterculture, and the Klezmer Revival Claire Marissa Gogan Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History David P. Cline, Co-Chair Brett L. Shadle, Co-Chair Rachel B. Gross 4 May 2016 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Identity, Klezmer, Jewish, 20th Century, Folk Revival Copyright 2016 by Claire M. Gogan To Play Jewish Again: Roots, Counterculture, and the Klezmer Revival Claire Gogan ABSTRACT Klezmer, a type of Eastern European Jewish secular music brought to the United States in the late 19th and early 20th century, originally functioned as accompaniment to Jewish wedding ritual celebrations. In the late 1970s, a group of primarily Jewish musicians sought inspiration for a renewal of this early 20th century American klezmer by mining 78 rpm records for influence, and also by seeking out living klezmer musicians as mentors. Why did a group of Jewish musicians in the 1970s through 1990s want to connect with artists and recordings from the early 20th century in order to “revive” this music? What did the music “do” for them and how did it contribute to their senses of both individual and collective identity? How did these musicians perceive the relationship between klezmer, Jewish culture, and Jewish religion? Finally, how was the genesis for the klezmer revival related to the social and cultural climate of its time? I argue that Jewish folk musicians revived klezmer music in the 1970s as a manifestation of both an existential search for authenticity, carrying over from the 1960s counterculture, and a manifestation of a 1970s trend toward ethnic cultural revival. -

Core 1..230 Hansard

House of Commons Debates VOLUME 148 Ï NUMBER 435 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 42nd PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Monday, June 17, 2019 Speaker: The Honourable Geoff Regan CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 29155 HOUSE OF COMMONS Monday, June 17, 2019 The House met at 11 a.m. therapy because they cannot afford the costs of the supplies, devices and medications. The impacts of this are far reaching. Unable to comply with their therapy, it puts people at increased risk of serious health complications. In addition to the human impact, this adds Prayer strain to our health care system, as it must deal with completely avoidable emergency interventions. It does not need to be this way. New Democrats, since the time we won the fight for medicare in PRIVATE MEMBERS' BUSINESS this country under Tommy Douglas, believe that our work will not Ï (1100) be done until we also have a universal public pharmacare plan. The [English] health and financial impacts of not having a universal public pharmacare plan are as clear as day when we look at the impacts of DIABETES AWARENESS MONTH diabetes in this country. We must also keep in mind that prevention The House resumed from May 28 consideration of the motion. is cheaper than intervention. We know that there are other social Ms. Jenny Kwan (Vancouver East, NDP): Mr. Speaker, I am policies we can engage in to reduce the risk of people developing very happy to engage in this important discussion. In 2014, the Steno diabetes in the first place. -

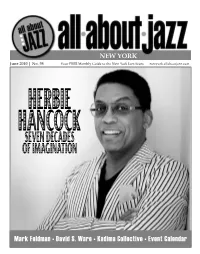

June 2010 Issue

NEW YORK June 2010 | No. 98 Your FREE Monthly Guide to the New York Jazz Scene newyork.allaboutjazz.com HERBIE HANCOCKSEVEN DECADES OF IMAGINATION Mark Feldman • David S. Ware • Kadima Collective • Event Calendar NEW YORK Despite the burgeoning reputations of other cities, New York still remains the jazz capital of the world, if only for sheer volume. A night in NYC is a month, if not more, anywhere else - an astonishing amount of music packed in its 305 square miles (Manhattan only 34 of those!). This is normal for the city but this month, there’s even more, seams bursting with amazing concerts. New York@Night Summer is traditionally festival season but never in recent memory have 4 there been so many happening all at once. We welcome back impresario George Interview: Mark Feldman Wein (Megaphone) and his annual celebration after a year’s absence, now (and by Sean Fitzell hopefully for a long time to come) sponsored by CareFusion and featuring the 6 70th Birthday Celebration of Herbie Hancock (On The Cover). Then there’s the Artist Feature: David S. Ware always-compelling Vision Festival, its 15th edition expanded this year to 11 days 7 by Martin Longley at 7 venues, including the groups of saxophonist David S. Ware (Artist Profile), drummer Muhammad Ali (Encore) and roster members of Kadima Collective On The Cover: Herbie Hancock (Label Spotlight). And based on the success of the WinterJazz Fest, a warmer 9 by Andrey Henkin edition, eerily titled the Undead Jazz Festival, invades the West Village for two days with dozens of bands June. -

Constituency Offices in Focus

Volume 37, No. 2 Summer 2014 Constituency Offices in Focus Journal of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association, Canadian Region Regional Executive Committee, CPA (June 30, 2014) PRESIDENT REGIONAL REPRESENTATIVES Gene Zwozdesky, Alberta Russ Hiebert, Federal Branch Ross Wiseman, Newfoundland and Labrador FIRST VICE-PRESIDENT Gene Zwozdesky, Alberta Dale Graham, New Brunswick CHAIR OF THE CWP, CANADIAN SECTION SECOND VICE-PRESIDENT (Commonwealth Women Parliamentarians) Linda Reid, British Columbia Myrna Driedger, Manitoba PAST PRESIDENT EXECUTIVE SECRETARY-TREASURER Jacques Chagnon, Québec Blair Armitage Members of the Regional Council (June 30, 2014) HOUSE OF COMMONS SENATE Andrew Scheer, Speaker Noël Kinsella, Speaker Audrey O’Brien, Clerk Gary O’Brien, Clerk ALBERTA NOVA SCOTIA Gene Zwozdesky, Speaker Kevin Murphy, Speaker David McNeil, Secretary Neil Ferguson, Secretary BRITISH COLUMBIA ONTARIO Linda Reid, Speaker Dave Levac, Speaker Craig James, Secretary Deborah Deller, Secretary CANADIAN FEDERAL BRANCH PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND Joe Preston, Chair Carolyn Bertram, Speaker Elizabeth Kingston, Secretary Charles MacKay, Secretary MANITOBA QUÉBEC Daryl Reid, Speaker Jacques Chagnon, Speaker Patricia Chaychuk, Secretary Émilie Bevan, Secretary NEW BRUNSWICK SASKATCHEWAN Dale Graham, Speaker Dan D’Autremont, Speaker Donald Forestell, Secretary Gregory Putz, Secretary NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR NORTHWEST TERRITORIES Ross Wiseman, Speaker Jackie Jacobson, Speaker Sandra Barnes, Secretary Tim Mercer, Secretary NUNAVUT YUKON George Qulaut, Speaker -

Naftule Brandwein, Dave Tarras and the Shifting Aesthetics in the Contemporary Klezmer Landscape

WHAT A JEW MEANS IN THIS TIME: Naftule Brandwein, Dave Tarras and the shifting aesthetics in the contemporary klezmer landscape Joel E. Rubin University of Virginia Clarinetists Naftule Brandwein (1884-1963) and Dave Tarras (1895-1989) were the two leading performers of Jewish instrumental klezmer music in New York during the first half of the 20th century. Due to their virtuosity, colorful personalities and substantial recorded legacy, it was the repertoire and style of these two musicians that served as the major influence on the American (and transnational) klezmer revival movement from its emergence in the mid-1970s at least until the mid-1990s.1 Naftule Brandwein playing a solo in a New York catering hall, ca. late 1930s. Photo courtesy of Dorothea Goldys-Bass 1 Dave Tarras playing a solo in a New York catering hall, ca. early 1940s. Photo courtesy of the Center for Traditional Music and Dance, New York. Since that time, the influence of Brandwein and Tarras on contemporary klezmer has waned to some extent as a younger generation of klezmer musicians, many born in the 1970s and 1980s, has adopted new role models and the hegemony of the Brandwein-Tarras canon has been challenged.2 In particular, beginning in the early 1990s and continuing to the present, a parallel interest has developed among many contemporary klezmer musicians in the eastern European roots of the tradition. At the same time, a tendency towards innovation and a fusing of traditional klezmer music of various historical periods and regions with a variety of styles has emerged. These include jazz, rhythm and blues, funk, Hip-Hop and Balkan music. -

Men of Canada 1891

THE CANADIAN ALBUM. * >*< * MEN OF CANADA; OR, SUCCESS BY EXAMPLE, g IN RELIGION, PATRIOTISM, BUSINESS, LAW, MEDICINE, EDUCATION AND AGRICULTURE; CONTAINING PORTRAITS OK SOME OK CANADA'S CHIEF BUSINESS MEN, STATESMEN, FARMERS, MEN OF THE LEARNED PROFESSIONS, AND OTHERS. ALSO, AN AUTHENTIC SKETCH OF THEIR LIVES. OBJECT LESSONS FOR THE PRESENT GENERATION AND EXAMPLES TO POSTERITY. EDITED BY REV. WM. COCHRANE, D.D., AUTHOR OF "FUTURE PUNISHMENT, OR DOES DEATH END PROBATION," "THE CHURCH AND THE COMMONWEALTH, ETC., ETC. 'THE PROPER STUDY OF MANKIND IS MAN. VOL. I. BRADLEY, GARRETSON & CO., BRANTFORD, ONTARIO,- 1891. n . OLIVER MOWAT, Q.C., Tache-Macdonald administrations. In M.P.P., LL.D., Premier of 1864 he was appointed to the Bench, Ontario, was born at King- and for eight years adorned the position. ston, Ont., July 22iid, 1820. His In 1872 he re-entered public life, and father came from Caitheneshire, Scot- became Premier of Ontario, and has land, to Canada in 1816. Mr. Mowat been representative of North Oxford received his education in Kingston, from that date to the present. He en- having among his fellow pupils Sir joys the confidence of Ontario as an John A. Macdonald and the late Hon. able, patriotic statesman, and despite of John Hillyard Cameron. He began the local Opposition and Dominion law with Mr. John A. Macdonald, then Government, maintains his large ma- practicing in Kingston. In the Rebel- jority. The many measures of legis- ' lion of 1837 y un Mowat joined the lation he has carried and his victories Royalists. After four years he re- before the Privy Council of England moved to Toronto, and completed his are known to all. -

Friday, May 28, 1999

CANADA VOLUME 135 S NUMBER 233 S 1st SESSION S 36th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, May 28, 1999 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire'' at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 15429 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, May 28, 1999 The House met at 10 a.m. named department or agency and the said motion shall be deemed adopted when called on ‘‘Motions’’ on the last sitting day prior to May 31; _______________ It is evident from the text I have just quoted that there are no provisions in the standing orders to allow anyone other than the Leader of the Opposition to propose this extension. Prayers D (1005 ) _______________ Furthermore, the standing order does not require that such a motion be proposed. The text is merely permissive. D (1000) I must acknowledge the ingenuity of the hon. member for POINTS OF ORDER Pictou—Antigonish—Guysborough in suggesting that an analo- gous situation exists in citation 924 of Beauchesne’s sixth edition ESTIMATES—SPEAKER’S RULING which discusses the division of allotted days among opposition parties. However, I must agree with the hon. government House leader when he concludes, on the issue of extension, that the The Acting Speaker (Mr. McClelland): Before we begin the standing orders leave the Speaker no discretionary power at all. day’s proceedings I would like to rule on the point of order raised Thus, I cannot grant the hon. member’s request to allow his motion by the hon. -

Quantitative Measurement of Parliamentary Accountability Using Text As Data: the Canadian House of Commons, 1945-2015 by Tanya W

Quantitative measurement of parliamentary accountability using text as data: the Canadian House of Commons, 1945-2015 by Tanya Whyte A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Political Science University of Toronto c Copyright 2019 by Tanya Whyte Abstract Quantitative measurement of parliamentary accountability using text as data: the Canadian House of Commons, 1945-2015 Tanya Whyte Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Political Science University of Toronto 2019 How accountable is Canada’s Westminster-style parliamentary system? Are minority parliaments more accountable than majorities, as contemporary critics assert? This dissertation develops a quanti- tative measurement approach to investigate parliamentary accountability using the text of speeches in Hansard, the historical record of proceedings in the Canadian House of Commons, from 1945-2015. The analysis makes a theoretical and methodological contribution to the comparative literature on legislative debate, as well as an empirical contribution to the Canadian literature on Parliament. I propose a trade-off model in which parties balance communication about goals of office-seeking (accountability) or policy-seeking (ideology) in their speeches. Assuming a constant context of speech, I argue that lexical similarity between government and opposition speeches is a valid measure of parlia- mentary accountability, while semantic similarity is an appropriate measure of ideological polarization. I develop a computational approach for measuring lexical and semantic similarity using word vectors and the doc2vec algorithm for word embeddings. To validate my measurement approach, I perform a qualitative case study of the 38th and 39th Parliaments, two successive minority governments with alternating governing parties.