The Last Station Recently I Observed, in Reviewing the Film “Bright

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christopher Plummer

Christopher Plummer "An actor should be a mystery," Christopher Plummer Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 Biography ................................................................................................................................. 4 Christopher Plummer and Elaine Taylor ............................................................................. 18 Christopher Plummer quotes ............................................................................................... 20 Filmography ........................................................................................................................... 32 Theatre .................................................................................................................................... 72 Christopher Plummer playing Shakespeare ....................................................................... 84 Awards and Honors ............................................................................................................... 95 Christopher Plummer Introduction Christopher Plummer, CC (born December 13, 1929) is a Canadian theatre, film and television actor and writer of his memoir In "Spite of Myself" (2008) In a career that spans over five decades and includes substantial roles in film, television, and theatre, Plummer is perhaps best known for the role of Captain Georg von Trapp in The Sound of Music. His most recent film roles include the Disney–Pixar 2009 film Up as Charles Muntz, -

Holiday TV Guide 2020

HolidayTV Better watch out 20th Century Fox Thirty years after premiering in theaters, this movie about a boy who protects his home from burglars at Christmastime is still entertaining viewers young and old. Kevin McCallister (Macaulay Culkin, “My Girl,” 1991) learns to be careful what he wishes for after his mom and dad accidentally leave him behind as they fly to Paris for the holidays in “Home Alone,” airing Thursday, Nov. 26, on Freeform. Holiday TV| Home Alone 30th Anniversary 30 years of holiday high jinx ‘Home Alone’ celebrates big milestone By Kyla Brewer TV Media their extended family scramble to make it to the airport in time to catch their flight. In the ensuing chaos and confusion, parents Kate (Catherine he holidays offer movie fans a treasure O’Hara, “Schitt’s Creek”) and Peter (John Heard, trove of options, old and new. Some are “Cutter’s Way,” 1981) forget young Kevin, who Tfunny, some are heartwarming, some are had been sent to sleep in the attic after causing a inspirational and a precious few are all of those ruckus the night before. The boy awakens to find things combined. One such modern classic is cel- his home deserted and believes that his wish for ebrating a milestone this year, and viewers won’t his family to disappear has come true. want to miss it. At first, Kevin’s new parent-and-sibling-free Macaulay Culkin (“My Girl,” 1991) stars as Kevin existence seems ideal as he jumps on his parents’ McCallister, a boy who is left behind when his fam- bed, raids his big brother’s room, eats ice cream ily goes on vacation during the holidays, in “Home for supper and watches gangster movies. -

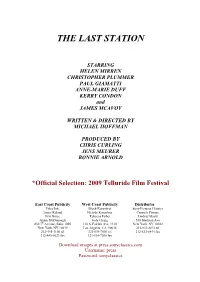

The Last Station

Mongrel Media Presents The Last Station A Film by Michael Hoffman (112 min, Germany, Russia, UK, 2009) Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html THE LAST STATION STARRING HELEN MIRREN CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER PAUL GIAMATTI ANNE-MARIE DUFF KERRY CONDON and JAMES MCAVOY WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY MICHAEL HOFFMAN PRODUCED BY CHRIS CURLING JENS MEURER BONNIE ARNOLD *Official Selection: 2009 Telluride Film Festival SYNOPSIS After almost fifty years of marriage, the Countess Sofya (Helen Mirren), Leo Tolstoy’s (Christopher Plummer) devoted wife, passionate lover, muse and secretary—she’s copied out War and Peace six times…by hand!—suddenly finds her entire world turned upside down. In the name of his newly created religion, the great Russian novelist has renounced his noble title, his property and even his family in favor of poverty, vegetarianism and even celibacy. After she’s born him thirteen children! When Sofya then discovers that Tolstoy’s trusted disciple, Chertkov (Paul Giamatti)—whom she despises—may have secretly convinced her husband to sign a new will, leaving the rights to his iconic novels to the Russian people rather than his very own family, she is consumed by righteous outrage. This is the last straw. Using every bit of cunning, every trick of seduction in her considerable arsenal, she fights fiercely for what she believes is rightfully hers. -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

Men's Ministry/Spiritual Transformation Resources & References

MEN’S MINISTRY/SPIRITUAL TRANSFORMATION RESOURCES & REFERENCES Rev. Dr. Paul Koch, Regional Ministry Team 636-221-7065, [email protected] Small Group Resources and Discussion Books An asterisk (*) indicates that Paul Koch has published a set of discussion guides for this book, under the series title: “Conversations at the Core.” They are available to download through the Chalice Pages tab at ChalicePress.com. Each was well received in his Wild Wise Men group. For more information on Men’s Ministries, please visit my website, www.BeABetterBrother.org *Albom, Mitch. Have a Little Faith. New York: Hyperion, 2009. *_____. Tuesdays with Morrie: An Old Man, a Young Man, and Life’s Greatest Lesson. New York: Broadway Books, 1997. *Grisham, John. Calico Joe. New York: Doubleday, 2012. Groff, Kent Ira. Journeymen: A Spiritual Guide for Men. Nashville: Upper Room Books, 1999. *Hillenbrand, Laura. Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption. New York: Random House, 2010. *Hugo, Victor. Les Miserables.1863 (various translations; abridged versions or watching a live or filmed stage production or the movie will work). Koch, Jr., Paul B. Conversations at the Core. St. Louis: Chalice Pages / Chalice Press, 2014. *Marx, Jeffrey. Season of Life: A Football Star, a Boy, a Journey to Manhood. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003. *Miller, Donald. A Million Miles in a Thousand Years: How I Learned to Live a Better Story. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2009 Nouwen, Henri J.M. The Return of the Prodigal Son: A Story of Homecoming. New York: Image Books, 1994. Rohr, Richard O.F.M. Falling Upward: A Spirituality for the Two Halves of Life AND Companion Journal. -

Movie Data Analysis.Pdf

FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM COGS108 Final Project Group Members: Yanyi Wang Ziwen Zeng Lingfei Lu Yuhan Wang Yuqing Deng Introduction and Background Movie revenue is one of the most important measure of good and bad movies. Revenue is also the most important and intuitionistic feedback to producers, directors and actors. Therefore it is worth for us to put effort on analyzing what factors correlate to revenue, so that producers, directors and actors know how to get higher revenue on next movie by focusing on most correlated factors. Our project focuses on anaylzing all kinds of factors that correlated to revenue, for example, genres, elements in the movie, popularity, release month, runtime, vote average, vote count on website and cast etc. After analysis, we can clearly know what are the crucial factors to a movie's revenue and our analysis can be used as a guide for people shooting movies who want to earn higher renveue for their next movie. They can focus on those most correlated factors, for example, shooting specific genre and hire some actors who have higher average revenue. Reasrch Question: Various factors blend together to create a high revenue for movie, but what are the most important aspect contribute to higher revenue? What aspects should people put more effort on and what factors should people focus on when they try to higher the revenue of a movie? http://localhost:8888/nbconvert/html/Desktop/MyProjects/Pr_085/FinalProject.ipynb?download=false Page 1 of 62 FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM Hypothesis: We predict that the following factors contribute the most to movie revenue. -

Carnival Films and ITV and MASTERPIECE on PBS Announce Paul Giamatti to Join Downton Abbey

Carnival Films and ITV and MASTERPIECE on PBS announce Paul Giamatti to join Downton Abbey Carnival Films, ITV and MASTERPIECE on PBS/WGBH today announced that Emmy®, Golden Globe® and SAG® award winner Paul Giamatti (John Adams, Sideways, Barney’s Version, Cinderella Man) has joined the cast of the Emmy® and Golden Globe® award-winning drama, Downton Abbey. Giamatti will play Cora’s maverick, playboy brother Harold in the season finale. He will be starring alongside Shirley MacLaine and the regular cast members for the dramatic climax to season 4. He joins new cast members Dame Kiri Te Kanawa, Tom Cullen, Julian Ovenden, Nigel Harman, Joanna David and Gary Carr who are all set to star in the fourth season. Carnival Films’ Managing Director, Gareth Neame said, “We're excited that Paul Giamatti will be joining us on Downton to play Cora's brother Harold, the rather free-spirited uncle to Mary and Edith. We can't wait to see him work alongside Shirley MacLaine, who are both sure to upset the Grantham's apple cart in this year's finale.” Downton Abbey season 4 will air on MASTERPIECE on PBS starting January 5, 2014. The new season will see the return of Shirley MacLaine as Martha Levinson alongside series regulars Hugh Bonneville, Maggie Smith, Michelle Dockery and Jim Carter. In the U.S., 24 million viewers tuned in to the third season of Downton Abbey on MASTERPIECE, making it the highest-rated PBS drama of all time. The finale was the #1 show of the night, beating all broadcast and cable competition in prime time. -

The Last Station

THE LAST STATION STARRING HELEN MIRREN CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER PAUL GIAMATTI ANNE-MARIE DUFF KERRY CONDON and JAMES MCAVOY WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY MICHAEL HOFFMAN PRODUCED BY CHRIS CURLING JENS MEURER BONNIE ARNOLD *Official Selection: 2009 Telluride Film Festival East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Falco Ink. Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Janice Roland Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Erin Bruce Rebecca Fisher Lindsay Macik Annie McDonough Judy Chang 550 Madison Ave 850 7th Avenue, Suite 1005 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 New York, NY 10022 New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 212-833-8833 tel 212-445-7100 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8844 fax 212-445-0623 fax 323-634-7030 fax Download images at press.sonyclassics.com Username: press Password: sonyclassics SYNOPSIS After almost fifty years of marriage, the Countess Sofya (Helen Mirren), Leo Tolstoy’s (Christopher Plummer) devoted wife, passionate lover, muse and secretary—she’s copied out War and Peace six times…by hand!—suddenly finds her entire world turned upside down. In the name of his newly created religion, the great Russian novelist has renounced his noble title, his property and even his family in favor of poverty, vegetarianism and even celibacy. After she’s born him thirteen children! When Sofya then discovers that Tolstoy’s trusted disciple, Chertkov (Paul Giamatti)—whom she despises—may have secretly convinced her husband to sign a new will, leaving the rights to his iconic novels to the Russian people rather than his very own family, she is consumed by righteous outrage. This is the last straw. -

95 Updated Facts/Trivia Copy

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2014 NOMINATIONS (updated as of July 21, 2014) 2014 PRIMETIME EMMY AWARDS 1 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2013 Behind The Candelabra – 11 Boardwalk Empire – 5 66th Annual Tony Awards – 4 Saturday Night Live – 4 The Big Bang Theory - 3 Breaking Bad – 3 Disney Mickey Mouse Croissant de Triomphe – 3 House of Cards -3 Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence In The House of God - 3 30 Rock - 2 The 55th Annual Grammy Awards – 2 American Horror Story: Asylum- 2 American Masters – 2 Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown – 2 The Colbert Report – 2 Da Vinci’s Demons – 2 Deadliest Catch – 2 Game of Thrones - 2 Homeland – 2 How I Met Your Mother - 2 The Kennedy Center Honors - 2 The Men Who Built America - 2 Modern Family – 2 Nurse Jackie – 2 Veep – 2 The Voice - 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2013 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Modern Family Drama Series: Breaking Bad Miniseries or Movie: Behind The Candelabra Reality-Competition Program: The Voice Variety, Music or Comedy Series: The Colbert Report PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Julia Louis-Dreyfus (Veep) Lead Actor: Jim Parsons (The Big Bang Theory) Supporting Actress: Merritt Wever (Nurse Jackie) Supporting Actor: Tony Hale (Veep) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Claire Danes (Homeland) Lead Actor: Jeff Daniels (The Newsroom) Supporting Actress: Anna Gunn (Breaking Bad) Supporting Actor: Bobby Cannavale (Boardwalk Empire) Miniseries/Movie: Lead Actress: Laura Linney (The Big C: Hereafter) Lead Actor: Michael Douglas (Behind The Candelabra) Supporting Actress: Ellen Burstyn (Political Animals) Supporting -

Includes Our Main Attractions and Special Programs 215 345 6789

County Theater 70 PreviewsDECEMBER 2009 – MARCH 2010 Penelope Cruz in BROKEN EMBRACES Cruz in BROKEN Penelope INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS C OUNTY T HEATER.ORG 215 345 6789 Welcome to the nonprofit County Theater The County Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. When will films play? ADMISSION Main Attractions. Our main films play week-to-week from General ............................................................$9.00 Fridays through Thursdays. Every Monday we determine what Members .........................................................$4.75 new films will start that Friday and what current films will end on Thursday or continue for another week. All of our main Seniors (62+) attraction films are subject to this weekly decision. After we Students (w/ID) & Children (<18). ................$6.75 decide on Mondays, we immediately let you know our plans on Matinees our website, on our hotline, and in our weekly email blast. (For Mon-Fri before 5:00 more info on the business of booking films, visit our website.) Sat & Sun before 2:30 .....................................$6.75 Wed Early Matinee (before 2:30 pm) ...............$4.75 Special Programs. Our special programs are generally Affiliated Theaters Members* ...........................$5.75 scheduled for specific dates and times, which are listed in this Previews brochure and on our website. Make sure that we have your email address *Affiliated Theaters Members We can keep you up-to-date on all of our film scheduling and The County Theater, the Ambler Theater, and the Bryn Mawr events via our weekly email mail notices. Visit our website to Film Institute have reciprocal admission benefits. Your County sign up and then stay plugged into our latest news. -

Parkland (2013) LOGIN

ABOUT CONTACT SUBSCRIBE ADVERTISE SUBMIT YOUR FILM FOR REVIEW PRETTY CLEVER T-SHIRTS Search ... FEATURE SECTIONS COLUMNS MOVIE LISTS MOVIE REVIEWS MOVIE SITES FESTIVALS DIRECTORS Home » Movie Reviews » Modern Times » TIFF13 Review: Parkland (2013) LOGIN MODERN TIMES Username Password Remember Me Login → Register Lost Password VISIT THE PRETTY CLEVER T-SHIRTS SHOP TIFF13 Review: Parkland (2013) BUY A ROCKIN' T-SHIRT Posted by Brandy Dean September 5, 2013 0 Comment 2115 views SUPPORT PRETTY CLEVER FILMS Like 4 2 17 1 It’s an old question (pretty much 50 years old to be precise): Where were you when J.F.K. was shot? In his new star-studded docudrama Parkland, first time feature director Peter Landesman poses this question. Again. While Parkland is stylish and packed to the rafters with talented performers, it brings nothing new to Kennedyana. Parkland focuses pretty tightly on the three days following Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas, TX. Each new character (and there are so, so many of them) is another famous face, but instead of lending weight to the proceedings, this who’s who of Hollywood starts feeling like some cinematic version of Where’s Waldo? Look it’s Billy Bob Thornton! Look it’s Zac Effron! Look it’s Paul Giamatti! Because the roles are so tiny and the characters so narrowly developed, the actors can’t help but overact. Giamatti is actually quite nuanced as Zapruder, but with mere minutes of screen times it comes off as blatant scenery chewing. I’m not a Kennedy-conspiracy theorist, but I could play one on television and here too Parkland has some issues. -

The Fisher King

Movies & Languages 2012-2013 The Ides of March About the movie (subtitled version) DIRECTOR George Clooney YEAR / COUNTRY 2011 / USA GENRE Drama ACTORS Ryan Gosling, George Clooney, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Paul Giamatti, Marisa Tomei PLOT Stephen Myers is an idealist and is brilliant at communications. He is second in command of Governor Mike Morris's presidential campaign, and is a true believer in the politics of Morris. In the middle of the Ohio primary, the campaign manager of Morris's opponent asks Myers to meet and offers him a job. At the same Morris's attempt to win the endorsement of a powerful North Carolina Senator hits a snag. A young campaign intern, Molly Stearns, gets Stephen's romantic attention, but has an important secret that could determine the fate of Morris's campaign. In the end Stephen must decide what's more important: career, victory, or virtue. The Ides of March was featured as the opening film at the 68th Venice International Film Festival. Although not winning any major awards it received generally positive reviews from most film critics. LANGUAGE Standard American English. GRAMMAR The Imperative We use the imperative for direct orders and also for a variety of other purposes. Stress and intonation, gesture, facial expression and, above all, situation and context indicate whether the use of this form is friendly, abrupt, angry, impatient, persuasive, etc. The imperative form is the same as the bare infinitive. Here are some examples: Affirmative form (base form of the verb) Wait! Negative short form (Don't + base form) Don't wait! Emphatic form (Do + base form) Do wait a moment! Addressing someone (e.g.