Randall Jobe Oral History Interview Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gay Marriage Party Ends For

'At Last* On her way to Houston, pop diva Cyndi Lauper has a lot to say. Page 15 voicewww.houstonvoice.com APRIL 23, 2004 THIRTY YEARS OF NEWS FOR YOUR LIFE. AND YOUR STYLE. Gay political kingmaker set to leave Houston Martin's success as a consultant evident in city and state politics By CHRISTOPHER CURTIS Curtis Kiefer and partner Walter Frankel speak with reporters after a Houston’s gay and lesbian com circuit court judge heard arguments last week in a lawsuit filed by gay munity loses a powerful friend and couples and the ACLU charging that banning same-sex marriages is a ally on May 3, when Grant Martin, violation of the Oregon state Constitution. (Photo by Rick Bowmer/AP) who has managed the campaigns of Controller Annise Parker, Council member Ada Edwards, Texas Rep. Garnet Coleman and Sue Lovell, is moving to San Francisco. Back in 1996 it seemed the other Gay marriage way around: Martin had moved to Houston from San Francisco after ending a five-year relationship. Sue Lovell, the former President party ends of the Houston Gay and Lesbian Political Caucus (PAC), remembers first hearing of Martin through her friend, Roberta Achtenberg, the for mer Clinton secretary of Fair for now Housing and Equal Opportunity. “She called me and told me I have a dear friend who is moving back to Ore. judge shuts down weddings, Houston and I want you to take Political consultant Grant Martin, the man behind the campaigns of Controller Annise Parker, good care of him.” but orders licenses recognized Council member Ada Edwards, Texas Rep. -

Youth Count 2.0!

Youth Count 2.0! Full Report of Findings May 13, 2015 Sarah C. Narendorf, PhD, LCSW Diane M. Santa Maria, DrPH, RN Jenna A. Cooper, LMSW i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS YouthCount 2.0! was conducted by the University of Houston Graduate College of Social Work in collaboration with the University of Texas School of Nursing and support from the University of Houston-Downtown. The original conceptualization of the study and preliminary study methods were designed under the leadership of Dr. Yoonsook Ha at Boston University with support from Dr. Diane Santa Maria and Dr. Noel Bezette-Flores. The study implementation was led by Dr. Sarah Narendorf and Dr. Diane Santa Maria and coordinated by Jenna Cooper, LMSW. The authors wish to thank the Greater Houston Community Foundation Fund to End Homelessness for their generous support of the project and the Child and Family Innovative Research Center at the University of Houston Graduate College of Social Work for additional support. The interest and enthusiasm for YouthCount 2.0! began with the Homeless Youth Network who assisted in funding the initial stages of the project along with The Center for Public Service and Family Strengths at the University of Houston- Downtown.. Throughout the project we received whole-hearted support from service providers across Harris County. Special thanks to Covenant House Texas for making their staff available for outreach and supporting every aspect of the program, the Coalition for the Homeless for technical assistance and help with the HMIS data and to Houston reVisions -

Center for Public History

Volume 8 • Number 2 • spriNg 2011 CENTER FOR PUBLIC HISTORY Oil and the Soul of Houston ast fall the Jung Center They measured success not in oil wells discovered, but in L sponsored a series of lectures the dignity of jobs well done, the strength of their families, and called “Energy and the Soul of the high school and even college graduations of their children. Houston.” My friend Beth Rob- They did not, of course, create philanthropic foundations, but ertson persuaded me that I had they did support their churches, unions, fraternal organiza- tions, and above all, their local schools. They contributed their something to say about energy, if own time and energies to the sort of things that built sturdy not Houston’s soul. We agreed to communities. As a boy, the ones that mattered most to me share the stage. were the great youth-league baseball fields our dads built and She reflected on the life of maintained. With their sweat they changed vacant lots into her grandfather, the wildcatter fields of dreams, where they coached us in the nuances of a Hugh Roy Cullen. I followed with thoughts about the life game they loved and in the work ethic needed later in life to of my father, petrochemical plant worker Woodrow Wilson move a step beyond the refineries. Pratt. Together we speculated on how our region’s soul—or My family was part of the mass migration to the facto- at least its spirit—had been shaped by its famous wildcat- ries on the Gulf Coast from East Texas, South Louisiana, ters’ quest for oil and the quest for upward mobility by the the Valley, northern Mexico, and other places too numerous hundreds of thousands of anonymous workers who migrat- to name. -

067 Risky Business

Risky Business: The Duque Government’s Approach to Peace in Colombia Latin America Report N°67 | 21 June 2018 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 149 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The FARC’s Transition to Civilian Life ............................................................................. 3 III. Rural Reform and Illicit Crop Substitution ...................................................................... 7 IV. Transitional Justice .......................................................................................................... 11 V. Security Threats ................................................................................................................ 14 VI. Conclusion ........................................................................................................................ 19 APPENDICES A. Colombian Presidential Run-off Results by Department ................................................ 21 B. Map of Colombia ............................................................................................................. 22 C. Acronyms ......................................................................................................................... -

Risky Business Northern California Authority Northern California

Municipal Pooling Municipal Pooling Authority Risky Business Northern California Authority Northern California How to Get Your Sleep Back… (Continued from Page 1) WINTER IS COMING—PREPARE Risky Business Fall Here are a few of the recommended ways to blunt the impact of COVID-19 2020 disruption on your sleep: YOUR HOME FOR THE COLD! • Get up at the same time each day – This is important even on the week- ends, so your brain and body get into a rhythm. Avoid sleeping in or napping Before the weather gets too cold, you should How to Get Your Sleep Back on Track in the afternoon. protect your house and family from the ele- • Get outside early – Natural sunlight tells our brain it is daytime so your brain ments. Here are some essential areas to check: can start preparing to help you perform your best and help you to wind down at the same time at night Roof COVID-19 has disrupted nearly every aspect of • Keep a routine – A routine will aid productivity, improve mood and expend the Look for missing shingles, cracked flashing, everyone’s life, and sleep is no exception. But be careful, says same amount of energy each day to best earn quality sleep onset at the same and broken overhanging tree limbs. UH clinical psychologist Carolyn Ievers-Landis, PhD -- the time each night. • Stay physically active – Exercising early in the day also helps to earn sleep Check the chimney for mortar deterioration irregular sleep schedules created by COVID-19 can have a at the same time each night. -

Visionary's Dream Led to Risky Business Opaque Deals, Accounting Sleight of Hand Built an Energy Giant and Ensured Its Demise

Visionary's Dream Led to Risky Business Opaque Deals, Accounting Sleight of Hand Built an Energy Giant and Ensured Its Demise By Peter Behr and April Witt Washington Post Staff Writers Sunday, July 28, 2002; Page A01 First of five articles For Vince Kaminski, the in-house risk-management genius, the fall of Enron Corp. began one day in June 1999. His boss told him that Enron President Jeffrey K. Skilling had an urgent task for Kaminski's team of financialanalysts. A few minutes later, Skilling surprised Kaminski by marching into his office to explain. Enron's investment in a risky Internet start-up called Rhythms NetConnections had jumped $300 million in value. Because of a securities restriction, Enron could not sell the stock immediately. But the company could and did count the paper gain as profit. Now Skilling had a way to hold on to that windfall if the tech boom collapsed and the stock dropped. Much later, Kaminski would come to see Skilling's command as a turning point, a moment in which the course of modern American business was fundamentally altered. At the time Kaminski found Skilling's idea merely incoherent, the task patently absurd. When Kaminski took the idea to his team -- world-class mathematicians who used arcane statistical models to analyze risk -- the room exploded in laughter. The plan was to create a private partnership in the Cayman Islands that would protect -- or hedge -- the Rhythms investment, locking in the gain. Ordinarily, Wall Street firms would provide such insurance, for a fee. But Rhythms was such a risky stock that no company would have touched the deal for a reasonable price. -

Summer SAMPLER VOLUME 13 • NUMBER 3 • SUMMER 2016

Summer SAMPLER VOLUME 13 • NUMBER 3 • SUMMER 2016 CENTER FOR PUBLIC HISTORY Published by Welcome Wilson Houston History Collaborative Last LETTER FROM EDITOR JOE PRATT Ringing the History Bell fter forty years of university In memory of my Grandma Pratt I keep her dinner bell, Ateaching, with thirty years at which she rang to call the “men folks” home from the University of Houston, I will re- fields for supper. After ringing the bell long enough to tire at the end of this summer. make us wish we had a field to retreat to, Felix, my For about half my years at six-year old grandson, asked me what it was like to UH, I have run the Houston live on a farm in the old days. We talked at bed- History magazine, serving as a time for almost an hour about my grandparent’s combination of editor, moneyman, life on an East Texas farm that for decades lacked both manager, and sometimes writer. In the electricity and running water. I relived for him my memo- Joseph A. Pratt first issue of the magazine, I wrote: ries of regular trips to their farm: moving the outhouse to “Our goal…is to make our region more aware of its history virgin land with my cousins, “helping” my dad and grandpa and more respectful of its past.” We have since published slaughter cows and hogs and hanging up their meat in the thirty-four issues of our “popular history magazine” devot- smoke house, draw- ed to capturing and publicizing the history of the Houston ing water from a well region, broadly defined. -

Printable Schedule

CALENDAR OF EVENTS AUGUST – NOVEMBER 2021 281-FREE FUN (281-373-3386) | milleroutdoortheatre.com Photo by Nash Baker INFORMATION Glass containers are prohibited in all City of Houston parks. If you are seated Location in the covered seating area, please ensure that your cooler is small enough to fit under your seat in case an emergency exit is required. 6000 Hermann Park Drive, Houston, TX 77030 Smoking Something for Everyone Smoking is prohibited in Hermann Park and at Miller Outdoor Theatre, including Miller offers the most diverse season of professional entertainment of any Houston the hill. performance venue — musical theater, traditional and contemporary dance, opera, classical and popular music, multicultural performances, daytime shows for young Recording, Photography, & Remote Controlled Vehicles audiences, and more! Oh, and it’s always FREE! Audio/visual recording and/or photography of any portion of Miller Outdoor Theatre Seating presentations require the express written consent of the City of Houston. Launching, landing, or operating unmanned or remote controlled vehicles (such as drones, Tickets for evening performances are available online at milleroutdoortheatre.com quadcopters, etc.) within Miller Outdoor Theatre grounds— including the hill and beginning at 9 a.m. two days prior to the performance until noon on the day of plaza—is prohibited by park rules. performance. A limited number of tickets will be available at the Box Office 90 minutes before the performance. Accessibility Face coverings/masks are strongly encouraged for all attendees in the Look for and symbols indicating performances that are captioned for the covered seats and on the hill, unless eating or drinking, especially those hearing-impaired or audio described for the blind. -

Houston Astrodome Harris County, Texas

A ULI Advisory ServicesReport Panel A ULI Houston Astrodome Harris County, Texas December 15–19, 2014 Advisory ServicesReport Panel A ULI Astrodome2015_cover.indd 2 3/16/15 12:56 PM The Astrodome Harris County, Texas A Vision for a Repurposed Icon December 15–19, 2014 Advisory Services Panel Report A ULI A ULI About the Urban Land Institute THE MISSION OF THE URBAN LAND INSTITUTE is ■■ Sustaining a diverse global network of local practice to provide leadership in the responsible use of land and in and advisory efforts that address current and future creating and sustaining thriving communities worldwide. challenges. ULI is committed to Established in 1936, the Institute today has more than ■■ Bringing together leaders from across the fields of real 34,000 members worldwide, representing the entire estate and land use policy to exchange best practices spectrum of the land use and development disciplines. and serve community needs; ULI relies heavily on the experience of its members. It is through member involvement and information resources ■■ Fostering collaboration within and beyond ULI’s that ULI has been able to set standards of excellence in membership through mentoring, dialogue, and problem development practice. The Institute has long been rec- solving; ognized as one of the world’s most respected and widely ■■ Exploring issues of urbanization, conservation, regen- quoted sources of objective information on urban planning, eration, land use, capital formation, and sustainable growth, and development. development; ■■ Advancing land use policies and design practices that respect the uniqueness of both the built and natural environments; ■■ Sharing knowledge through education, applied research, publishing, and electronic media; and Cover: Urban Land Institute © 2015 by the Urban Land Institute 1025 Thomas Jefferson Street, NW Suite 500 West Washington, DC 20007-5201 All rights reserved. -

Eclipse-132-133-Compressed.Pdf

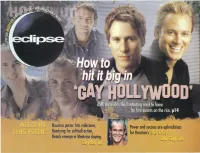

". Houston pastor hits milestone, Power and success are aphrodisiacs _.J .-J ~,...; ~ .r :::.J .:::.J'::.).....}.:!, Readying for softball action, for Houston's l{tdl. Gll~Y. Details emerge in Montrose slaying. ~l"-",;;;",,,,.~ \...t\ .• : CL,~/ l~8 ~ 1 I \.;,~~~~ j _~\2, 500 Levett, Suite 200 • Houston, TX77006 Phone: 713-529-8490 • Fax: 713-529-9531 A WindoYo! Media TollFree Out-of-State: 877-966-3342 Publication PUBLISHER t'sofficially hot in Houston, but the infusion of Window Media LLC All content of Eclipse queer culture into mainstream American society GENERAL MANAGER magazine copyrighted Mike Kitchens continues to make cool, steady headway. It's not ©2003 by Window I Media, LLC,and is just sodomy laws being thrown out in the U.S. via the ADVERTISING SALES protected by federal Brian Martin. Brett Cullum landmark Texas decision. It's the growing comfort of Tom Jones (Classifieds) copyright law and may not be reproduced non-gays to watch our lives portrayed on TV or to EDITORIAL DIRECTOR without the written blend our trends and style with theirs. Chris Crain consentof the publisher. The sexual orientation EDITORS of advertisers, Matt Hennie • Mike Fleming The July 15 debut of "Queer Eye for the Straight Guy" photographers, writers WEBMASTER and cartoonistspub- set new ratings records for cable channel Bravo, averag- Aram Vartian lished herein is ing some 1.64 million viewers. That's new evidence to neither inferred nor ART DIRECTOR implied. The appear- support the popularity of gay-themed shows. See our Rob Boeger ance of names or cover story on "Gay Hollywood" (Page 14) for more on pictorial representation PRODUCTION MANAGER how gay men are breaking out in "the business." John Nail does not necessarily indicate the sexual ori- GRAPHIC DESIGNERS entation of the person Joey Carolino or persons. -

SAM HOUSTON PARK: Houston History Through the Ages by Wallace W

PRESERVATION The 1847 Kellum-Noble House served as Houston Parks Department headquarters for many years. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS, Reproduction number HABS TEX, 101-HOUT, 4-1. SAM HOUSTON PARK: Houston History through the Ages By Wallace W. Saage he history of Texas and the history of the city grant from Austin’s widow, Mrs. J. F. L. Parrot, and laid Tof Houston are inextricably linked to one factor out a new city.1 They named it Houston. – land. Both Texas and Houston used the legacy of The growth of Sam Houston Park, originally called the land to encourage settlement, bringing in a great City Park, has always been closely related to the transfer multicultural mélange of settlers that left a lasting im- of land, particularly the physical and cultural evolution pression on the state. An early Mexican land grant to of Houston’s downtown region that the park borders. John Austin in 1824 led to a far-reaching development Contained within the present park boundaries are sites ac- plan and the founding of a new city on the banks of quired by the city from separate entities, which had erected Buffalo Bayou. In 1836, after the Republic of Texas private homes, businesses, and two cemeteries there. won its independence, brothers John Kirby Allen and Over the years, the city has refurbished the park, made Augustus C. Allen purchased several acres of this changes in the physical plant, and accommodated the increased use of automobiles to access a growing downtown. The greatest transformation of the park, however, grew out of the proposed demoli- tion of the original Kellum House built on the site in 1847. -

SHEILA PEPE Invites SONDRA PERRY Put Me Down

3400 MAIN STREET, SUITE 292 HOUSTON, TEXAS 77002 DIVERSEWORKS.ORG PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: --Jennifer Gardner, Deputy Director, DiverseWorks [email protected] / 713.223.8346 SHEILA PEPE invites SONDRA PERRY Put me down Gently: A Cooler Place + I'm Afraid I Can't Do That FRIDAY JUNE 10 6 – 7 pm: Patron and Member Preview 6:30 pm: Artist’s Talk 7 – 9 pm: Public Reception On view: June 11 – August 6, 2016 (Houston, TX, MAY 26, 2016) – DiverseWorks is pleased to announce the opening of SHEILA PEPE invites SONDRA PERRY -- Put me down Gently: A Cooler Place + I'm Afraid I Can't Do That, on view in the gallery at 3400 Main Street, June 11 – August 6. There will be a member’s preview and artist talk from 6 – 7 pm on Friday, June 10 with a public reception from 7 – 9 pm. Admission to DiverseWorks is free of charge Pepe’s exhibition in Houston is a commissioned installation that serves as an open meeting space and platform for several events, including a video installation by current MFAH Core Fellow Sondra Perry. With an interest in carving out space within solo exhibitions for young artists, Pepe invited Perry, working in video and performance, to respond to her augmented reinstallation of Put me down Gently, 2015. Each artist worked autonomously, yet their projects were hinged by shared resources, the color blue and an investment in improvisation within institutional frameworks. The exhibition evolved and two installations emerged – tethered to each other by ongoing conversations on craft, class, race, place and screens of projection.