Navigating Bluegrass Community on the Internet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canadian Country Music Association® Ultimate Fan

CONTEST OVERVIEW CANADIAN COUNTRY MUSIC ASSOCIATION® ULTIMATE FAN CONTEST OFFICIAL CONTEST RULES AND REGULATIONS The Canadian Country Music Association’s (CCMA®) Ultimate Fan Experience gives one lucky fan (and a guest) the chance to enjoy the ultimate country music package. Due to COVID-19, the 2020 prize will include elements of the amended programming as well as the regular programming for 2021. The 2020 winner will have the opportunity to virtually present the 2020 CCMA Fan’s Choice Award on the pre-taped award show airing on Global Television on September 27, 2020 (date subject to change). The winner will also have an opportunity to participate in a virtual meet and greet with a CCMA artist (to be determined by the CCMA) and up to 10 of their friends. Date and time to be determined. In 2021 the 2020 winner will receive free transportation, accommodations and event passes to Country Music Week in the Ontario host city. City to be announced. No purchase necessary. 1 HOW TO ENTER The Sponsor of this contest is “the Canadian Country Music Association,” and herein represented as “the Sponsor.” S tarting Tuesday Monday July 13, 2020, at 12:00 p.m. Eastern Time (ET) eligible entrants may enter the “CCMA Ultimate Fan” Contest (the “Contest”) by entering online at ccma.org/ultimatefan Eligible entrants must fully complete and submit the entire online Contest entry form, including full name, age, email address, province of residence, postal code and daytime phone number with area code. Incomplete entries will be disqualified. A fully completed online entry form will constitute one (1) entry into the Contest. -

2014 Joe Val Bluegrass Festival Preview

2014 Joe Val Bluegrass Festival Preview The 29th Joe Val Bluegrass Festival is quickly approaching, February 14 -16 at the Sheraton Framingham Hotel, in Framingham, MA. The event, produced by the Boston Bluegrass Union, is one of the premier roots music festivals in the Northeast. The festival site is minutes west of Boston, just off of the Mass Pike, and convenient to travelers from throughout the region. This award winning and family friendly festival features three days of top national performers across two stages, over sixty workshops and education programs, and around the clock activities. Among the many artists on tap are The Gibson Brothers, Blue Highway, Junior Sisk, IIIrd Tyme Out, Sister Sadie featuring Dale Ann Bradley, and a special reunion performance by The Desert Rose Band. This locally produced and internationally recognized bluegrass festival, produced by the Boston Bluegrass Union, was honored in 2006 when the International Bluegrass Music Association named it "Event of the Year." In May 2012, the festival was listed by USATODAY as one of Ten Great Places to Go to Bluegrass Festivals Single day and weekend tickets are on sale now and we strongly suggest purchasing tickets in advance. Patrons will save time at the festival and guarantee themselves a ticket. Hotel rooms at the Sheraton are sold out, but overnight lodging is still available and just minutes away, at the Doubletree by Hilton, in Westborough, MA. Details on the festival, including bands, schedules, hotel information, and online ticket purchase at www.bbu.org And visit the 29th Joe Val Bluegrass Festival on Facebook for late breaking festival news. -

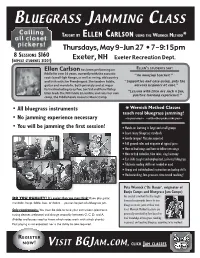

Bluegrass Jamming Class

BLUEGRASS JAMMING CLASS TAUGHT BY ELLEN CARLSON USING THE WERNICK METHOD* Thursdays, May 9-Jun 27 • 7-9:15pm 8 SESSIONS $160 (REPEAT STUDENTS $120!) Exeter, NH Exeter Recreation Dept. Ellen Carlson has been performing on ELLEN’S STUDENTS SAY: fiddle for over 35 years, currently with the acoustic “An amazing teacher! ” roots band High Range, as well as swing, old country and Irish with Jim Prendergast. She teaches fiddle, “Supportive and easy-going, puts the guitar and mandolin, both privately and at major nervous beginner at ease.” festival including Grey Fox, Joe Val and Pemi Valley. “Lessons with Ellen are such a fun, Ellen leads the NH Fiddle Ensemble and runs her own ” camp, the Fiddleheads Acoustic Music Camp. positive learning experience! • All bluegrass instruments * Wernick Method Classes teach real bluegrass jamming! • No jamming experience necessary * in your area * * with other pickers like you * • You will be jamming the first session! * Hands-on learning in large and small groups * Learn many bluegrass standards * Gentle tempos! Mistakes expected * Full ground rules and etiquette of typical jams * How to lead songs and how to follow new songs * How to find melodies, fake solos, sing harmony * Ear skills taught and emphasized, as in real bluegrass * Tab/note reading skills not needed or used * Group and individualized instruction on backup skills * Understanding, low-pressure, time-tested teaching! Pete Wernick (“Dr. Banjo”, originator of Banjo Camps and Bluegrass Jam Camps) has created a method that has taught DO YOU QUALIFY? It’s easier than you may think! If you play guitar, thousands nationwide how to fit into mandolin, banjo, fiddle, bass, or dobro… you can be part of a bluegrass jam. -

Flatpicking Guitar Magazine Index of Reviews

Flatpicking Guitar Magazine Index of Reviews All reviews of flatpicking CDs, DVDs, Videos, Books, Guitar Gear and Accessories, Guitars, and books that have appeared in Flatpicking Guitar Magazine are shown in this index. CDs (Listed Alphabetically by artists last name - except for European Gypsy Jazz CD reviews, which can all be found in Volume 6, Number 3, starting on page 72): Brandon Adams, Hardest Kind of Memories, Volume 12, Number 3, page 68 Dale Adkins (with Tacoma), Out of the Blue, Volume 1, Number 2, page 59 Dale Adkins (with Front Line), Mansions of Kings, Volume 7, Number 2, page 80 Steve Alexander, Acoustic Flatpick Guitar, Volume 12, Number 4, page 69 Travis Alltop, Two Different Worlds, Volume 3, Number 2, page 61 Matthew Arcara, Matthew Arcara, Volume 7, Number 2, page 74 Jef Autry, Bluegrass ‘98, Volume 2, Number 6, page 63 Jeff Autry, Foothills, Volume 3, Number 4, page 65 Butch Baldassari, New Classics for Bluegrass Mandolin, Volume 3, Number 3, page 67 William Bay: Acoustic Guitar Portraits, Volume 15, Number 6, page 65 Richard Bennett, Walking Down the Line, Volume 2, Number 2, page 58 Richard Bennett, A Long Lonesome Time, Volume 3, Number 2, page 64 Richard Bennett (with Auldridge and Gaudreau), This Old Town, Volume 4, Number 4, page 70 Richard Bennett (with Auldridge and Gaudreau), Blue Lonesome Wind, Volume 5, Number 6, page 75 Gonzalo Bergara, Portena Soledad, Volume 13, Number 2, page 67 Greg Blake with Jeff Scroggins & Colorado, Volume 17, Number 2, page 58 Norman Blake (with Tut Taylor), Flatpickin’ in the -

2022 Canadian Country Music Hall of Fame

2022 CANADIAN COUNTRY MUSIC HALL OF FAME RULES, REGULATIONS AND INDUCTION PROCESSES AS OF MAY 2021 Canadian Country Music Association 104 – 366 Adelaide Street East Toronto, ON M5A 3X9 [email protected] 416-947-1331 ccma.org TABLE OF CONTENTS: Summary………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..1 Overview………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..1 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)………………………………………………………………………………………………………….….1-2 2020 Induction Key Dates…………………..………………………………………………………………………………………………………….2 Hall of Fame Induction Process….……………………………………………………………………………………………………………....3-4 Induction Criteria…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……………4-5 SUMMARY The Canadian Country Music Association® (CCMA®) has been honouring Canadian Artists and Builders who have made long-term contributions to the growth and development of Canadian country music since 1984. Inductees into the Canadian Country Music Hall of Fame (Hall of Fame) are selected annually by their Canadian peers in the industry. The Hall of Fame is managed by the CCMA Board of Directors` appointed Hall of Fame Management Committee (Management Committee). OVERVIEW In 2022, there will be two (2) Hall of Fame Inductees selected: one (1) Artist and one (1) Builder. An Artist (solo, duo or group) is a professional performer (Canadian singer/musician) who has recorded and released music that has contributed significantly to the advancement of country music in Canada. A Builder is an individual who has contributed significantly to the advancement of country music in Canada. These individuals could include, but are not limited to: artist manager, booking agent, consultant, distributor, event and venue management, media, music publisher, producer, public relations, publication, publicity, radio, record company person, retailer, talent buyer/promoter and television/video. The information below is an overview of the Hall of Fame induction process and criteria for evaluating Artists and Builders for this honour. -

Adapting Traditional Kentucky Thumbpicking Repertoire for the Classical Guitar

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2015 Adapting Traditional Kentucky Thumbpicking Repertoire for the Classical Guitar Andrew Rhinehart University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Rhinehart, Andrew, "Adapting Traditional Kentucky Thumbpicking Repertoire for the Classical Guitar" (2015). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 44. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/44 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Songwriter Mike O'reilly

Interviews with: Melissa Sherman Lynn Russwurm Mike O’Reilly, Are You A Bluegrass Songwriter? Volume 8 Issue 3 July 2014 www.bluegrasscanada.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS BMAC EXECUTIVE President’s Message 1 President Denis 705-776-7754 Chadbourn Editor’s Message 2 Vice Dave Porter 613-721-0535 Canadian Songwriters/US Bands 3 President Interview with Lynn Russworm 13 Secretary Leann Music on the East Coast by Jerry Murphy 16 Chadbourn Ode To Bill Monroe 17 Treasurer Rolly Aucoin 905-635-1818 Open Mike 18 Interview with Mike O’Reilly 19 Interview with Melissa Sherman 21 Songwriting Rant 24 Music “Biz” by Gary Hubbard 25 DIRECTORS Political Correctness Rant - Bob Cherry 26 R.I.P. John Renne 27 Elaine Bouchard (MOBS) Organizational Member Listing 29 Gord Devries 519-668-0418 Advertising Rates 30 Murray Hale 705-472-2217 Mike Kirley 519-613-4975 Sue Malcom 604-215-276 Wilson Moore 902-667-9629 Jerry Murphy 902-883-7189 Advertising Manager: BMAC has an immediate requirement for a volunteer to help us to contact and present advertising op- portunities to potential clients. The job would entail approximately 5 hours per month and would consist of compiling a list of potential clients from among the bluegrass community, such as event-producers, bluegrass businesses, music stores, radio stations, bluegrass bands, music manufacturers and other interested parties. You would then set up a systematic and organized methodology for making contact and presenting the BMAC program. Please contact Mike Kirley or Gord Devries if you are interested in becoming part of the team. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Call us or visit our website Martha white brand is due to the www.bluegrassmusic.ca. -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand marking: or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

282 Newsletter

NEWSLETTER #282 COUNTY SALES P.O. Box 191 November-December 2006 Floyd,VA 24091 www.countysales.com PHONE ORDERS: (540) 745-2001 FAX ORDERS: (540) 745-2008 WELCOME TO OUR COMBINED CHRISTMAS CATALOG & NEWSLETTER #282 Once again this holiday season we are combining our last Newsletter of the year with our Christmas catalog of gift sugges- tions. There are many wonderful items in the realm of BOOKs, VIDEOS and BOXED SETS that will make wonderful gifts for family members & friends who love this music. Gift suggestions start on page 10—there are some Christmas CDs and many recent DVDs that are new to our catalog this year. JOSH GRAVES We are saddened to report the death of the great dobro player, Burkett Graves (also known as “Buck” ROU-0575 RHONDA VINCENT “Beautiful Graves and even more as “Uncle Josh”) who passed away Star—A Christmas Collection” This is the year’s on Sept. 30. Though he played for other groups like Wilma only new Bluegrass Christmas album that we are Lee & Stoney Cooper and Mac Wiseman, Graves was best aware of—but it’s a beauty that should please most known for his work with Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs, add- Bluegrass fans and all ing his dobro to their already exceptional sound at the height Rhonda Vincent fans. of their popularity. The first to really make the dobro a solo Rhonda has picked out a instrument, Graves had a profound influence on Mike typical program of mostly standards (JINGLE Auldridge and Jerry Douglas and the legions of others who BELLS, AWAY IN A have since made the instrument a staple of many Bluegrass MANGER, LET IT bands everywhere. -

1715 Total Tracks Length: 87:21:49 Total Tracks Size: 10.8 GB

Total tracks number: 1715 Total tracks length: 87:21:49 Total tracks size: 10.8 GB # Artist Title Length 01 Adam Brand Good Friends 03:38 02 Adam Harvey God Made Beer 03:46 03 Al Dexter Guitar Polka 02:42 04 Al Dexter I'm Losing My Mind Over You 02:46 05 Al Dexter & His Troopers Pistol Packin' Mama 02:45 06 Alabama Dixie Land Delight 05:17 07 Alabama Down Home 03:23 08 Alabama Feels So Right 03:34 09 Alabama For The Record - Why Lady Why 04:06 10 Alabama Forever's As Far As I'll Go 03:29 11 Alabama Forty Hour Week 03:18 12 Alabama Happy Birthday Jesus 03:04 13 Alabama High Cotton 02:58 14 Alabama If You're Gonna Play In Texas 03:19 15 Alabama I'm In A Hurry 02:47 16 Alabama Love In the First Degree 03:13 17 Alabama Mountain Music 03:59 18 Alabama My Home's In Alabama 04:17 19 Alabama Old Flame 03:00 20 Alabama Tennessee River 02:58 21 Alabama The Closer You Get 03:30 22 Alan Jackson Between The Devil And Me 03:17 23 Alan Jackson Don't Rock The Jukebox 02:49 24 Alan Jackson Drive - 07 - Designated Drinke 03:48 25 Alan Jackson Drive 04:00 26 Alan Jackson Gone Country 04:11 27 Alan Jackson Here in the Real World 03:35 28 Alan Jackson I'd Love You All Over Again 03:08 29 Alan Jackson I'll Try 03:04 30 Alan Jackson Little Bitty 02:35 31 Alan Jackson She's Got The Rhythm (And I Go 02:22 32 Alan Jackson Tall Tall Trees 02:28 33 Alan Jackson That'd Be Alright 03:36 34 Allan Jackson Whos Cheatin Who 04:52 35 Alvie Self Rain Dance 01:51 36 Amber Lawrence Good Girls 03:17 37 Amos Morris Home 03:40 38 Anne Kirkpatrick Travellin' Still, Always Will 03:28 39 Anne Murray Could I Have This Dance 03:11 40 Anne Murray He Thinks I Still Care 02:49 41 Anne Murray There Goes My Everything 03:22 42 Asleep At The Wheel Choo Choo Ch' Boogie 02:55 43 B.J. -

Buddy Miller's Majestic Silver Strings New West Records

Buddy Miller’s Majestic Silver Strings New West Records Buddy Miller, named Artist of the Decade by No Depression Magazine, teamed up with esteemed guitarists Marc Ribot, Bill Frisell and Greg Leisz to create The Majestic Silver Strings, a monumental musical experience to be released on CD, with bonus DVD, March 1, 2011 via New West Records. The Majestic Silver Strings, produced by Buddy, is his re-imagination of country songs, loaded with guitars, atmosphere and attitude. Guest vocalists on the album include Emmylou Harris, Patty Griffin, Shawn Colvin, Lee Ann Womack, Chocolate Genius, Ann McCrary and Julie Miller. Rounding out the band are Dennis Crouch on bass and Jay Bellerose on drums. The Majestic Silver Strings and the album’s guests are among the most well respected and in-demand current musicians. Making a record of this caliber was a dream and took luck of scheduling to make come true. A bonus DVD with concert footage of the first, and only performance to date with Buddy, Marc, Bill and Greg playing the tracks selected for this project, will be included with the CD. The musicians re-interpret classic country songs written by some of the most esteemed songwriters including Lefty Frizzell, Roger Miller and George Jones, whose hit “Why Baby Why” is sung by Buddy on the record. The band also tackles a few traditional compositions and several new songs including “God’s Wing’d Horse” written by Julie Miller and Bill Frisell. Many projects boast one guest vocalist; Buddy has six revered friends lending their voices to the recording including Emmylou Harris on “Why I’m Walkin’” and Lee Ann Womack on “Meds.” Buddy also does a duet of “I Want To Be With You Always” with Patty Griffin.