Children's Human Rights and Humanitarian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perception of the Experience of Domestic Violence by Women With

Perception of the Experience of Domestic Violence By Women with a Physical Disability by Jennifer Margery Mays BSocSci (Human Services) A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) Centre for Social Change Research School of Humanities and Human Services Queensland University of Technology February 2003 Declaration I, Jennifer Mays, declare that the work contained in this thesis is to the best of my knowledge and belief, original, except as acknowledged in the text and that the material has not been submitted, either in whole or part, for a degree at this or any other university. Signed: __________________________ Date: __________________________ i Abstract The disability movement drew attention to the struggle against the oppression of people of disability. The rise of disability activism contributed to increased awareness of the need for a social theory of disability, in order to account for the historical, social and economic basis of oppression. Emerging studies of disability issues by disability theorists, such as Sobsey (1994), highlighted the higher prevalence and nature of violence against people with a disability, in comparison to the general population. However, the limited research concerning women with a physical impairment experiencing domestic violence contributes to this social problem being underestimated in the community. Contemporary theoretical conceptualisations of both domestic violence and disability fail to explain the causal framework that leads to women who have a disability experiencing violent situations. Similarly, by explaining domestic violence as a solely socially constructed gender inequality and power differential, feminism provides insufficient recognition of the structural dimension of disability. -

Tesis Oct Draft 20.Pdf

A Manolo y Maruchi 2 Index Acknowledgments …………………………………………………………... 9 Introduction 1. Research topic, objectives and research questions…………………… 11 2. Research motivations…………………………………………………….. 14 3. Methodological strategies ………………………………………………. 15 4. Structure of the thesis…………………………………………………… 17 Chapter 1. Drawing cartographies, building epistemologies 1.1. Introduction…………………………………………………………. 22 1.2. Feminist (in)visible alliances: the importance of methodological bridges between the Humanities and the Social Sciences…………………………………. 24 1.2.1. Writing a scholarly piece in between the Social Sciences and the Humanities………………………………………………………… 25 1.2.2. Conceptual and political benefits of such a methodological bridge… 27 1.3. From post-modernist paradoxes for literary studies to post-humanist and post- colonial contributions: mapping literary theory………………………………….. 28 1.4. Literature and feminism: an overview………………………………………… 33 1.5. Entangling literature, technology and feminism ………..…………………… 37 1.5.1. Cyberfeminism: going political through the social net……………. 39 3 1.5.2. Feminist Science and Technology Studies: How might we theorize bodies as lived and/or as socially situated? ……………………………………….. 41 1.5.3. Third wave feminism: reinforcing dichotomies? …………………….. 43 1.6. New materialism: third wave feminist epistemology…………………………… 45 1.6.1. New materialist conversations: engaging with the critiques. ………. 46 1.6.2. Putting new materialism to work: implications for the relation between Toni Morrison and Facebook. ……………………………………………… 49 1.7. Conclusions………………………………………………………………… 51 Chapter 2. Diffractive methodology: relating gendered fluxes 2.1. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………. 53 2.2. Diffractive methodology……………………………………………………….. 54 2.3. Objective and research questions……………………………………………….. 56 2.4. Selecting the participants ……………………………………………………….. 57 2.4.1. Toni Morrison: performing feminist politics in the information society 58 2.4.2. Social Networking Sites: the case of Facebook………………………… 59 2.4.3. -

Materialist Feminism

9 / MATERIALIST FEMINISM A Reader in Class, Difference, and Women's Lives Edited by Rosemary Hennessy and Chrys Ingraham ROUTLEDGE New York & London Introduction Reclaiming Anticapitalist Feminism Rosemary Hennessy and Chrys Ingraham THE NEED FOR ClASS ANALYSIS OF WOMEN'S DIFFERENT LIVES We see this reader as a timely contribution to feminist struggle for transformative social change, a struggle which is fundamentally a class war over resources, knowledge, and power. Currently the richest 20 percent of humanity garners 83 percent of global income, while the poorest 20 percent of the world's people struggles to survive on just 1 percent of the global income (Sivard 1993; World Bank 1994). During the 1990s, as capitalism triumphantly secures its global reach, anticommunist ideologies hammer home socialism's inherent failure and the Left increasingly moves into the professional middle class. many of western feminism's earlier priorities-commitment to social transformation, attention to the political economy of patriarchy, analysis of the perva sive social structures that link and divide women~have been obscured or actively dismissed. Various forms of feminist cultural politics that take as their starting point gender, race, class, sexuality, or coalitions among them have increasingly displaced a systemic perspective that links the battle against women's oppression to a fight against capitalism. The archive collected in Materialist Feminism: A Reader in Class, Difference, and Women's Lives is a reminder that despite this trend feminists have continued to find in historical materialism a powerful theoretical and political resource. The tradi- . tion of feminist engagement with marxism emphasizes a perspective on social life that refuses to separate the materiality of meaning, identity, the body, state, or nation from the requisite division of labor that undergirds the scramble for profits in capitalism's global system. -

Summary Report General Assembly 2018 Contents

Summary Report General Assembly 2018 Contents 3 Welcome 20 Bumpy roads and warm welcomes 4 Introduction 22 Climate change 5 Special Assembly 23 Streams in the Desert 6 Making the Assembly more accessible 24 PW president in Middle East 7 Conferencing at the heart of the city 25 Chaplains 8 Ending paramilitary attacks 26 The mission at home 9 Education: Could do much better... 28 Difficult task – Active hope 10 Political and social issues to the fore 30 The ‘new’ Family Holiday 11 Belfast Agreement 31 Celebrating 10 years of SPUD 12 Relationships with other denominations 32 Learning disability 13 Doctrine Committee reports 33 Adult safeguarding 14 Presidential visit 34 Trinity House opens 15 Eighth Amendment Referendum 35 Team player 16 Visit of Pope Francis 36 World Development Appeal 17 Celebrating the Reformation 37 United Appeal 18 Solidarity in Egypt 38 Dates for your diary 19 Online course a first for Union 39 Vision for society The General Assembly is the governing and decision-making body of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland (PCI). The 2018 meeting was held in Assembly Buildings, Belfast from Monday 4 June until Friday 8 June. Minutes and full reports can be found at www.presbyterianireland.org/generalassembly. A review of each day’s proceedings can be found at www.presbyterianireland.org/news 2 Presbyterian Church in Ireland Welcome A very warm welcome to our fifth Summary Report, where you will find details of what was discussed and agreed at our 2018 General Assembly. Listening to debates at the time, there were several moments when I became so inspired and moved by what I was hearing that I almost forgot to put the resolutions to receive formally the reports that we had been discussing! The Clerk did his level-headed best to keep a watchful eye on me and I hope that no business was left suspended somewhere in the ether. -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

CNN Communications Press Contacts Press

CNN Communications Press Contacts Allison Gollust, EVP, & Chief Marketing Officer, CNN Worldwide [email protected] ___________________________________ CNN/U.S. Communications Barbara Levin, Vice President ([email protected]; @ blevinCNN) CNN Digital Worldwide, Great Big Story & Beme News Communications Matt Dornic, Vice President ([email protected], @mdornic) HLN Communications Alison Rudnick, Vice President ([email protected], @arudnickHLN) ___________________________________ Press Representatives (alphabetical order): Heather Brown, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @hlaurenbrown) CNN Original Series: The History of Comedy, United Shades of America with W. Kamau Bell, This is Life with Lisa Ling, The Nineties, Declassified: Untold Stories of American Spies, Finding Jesus, The Radical Story of Patty Hearst Blair Cofield, Publicist ([email protected], @ blaircofield) CNN Newsroom with Fredricka Whitfield New Day Weekend with Christi Paul and Victor Blackwell Smerconish CNN Newsroom Weekend with Ana Cabrera CNN Atlanta, Miami and Dallas Bureaus and correspondents Breaking News Lauren Cone, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @lconeCNN) CNN International programming and anchors CNNI correspondents CNN Newsroom with Isha Sesay and John Vause Richard Quest Jennifer Dargan, Director ([email protected]) CNN Films and CNN Films Presents Fareed Zakaria GPS Pam Gomez, Manager ([email protected], @pamelamgomez) Erin Burnett Outfront CNN Newsroom with Brooke Baldwin Poppy -

John J. Marchi Papers

John J. Marchi Papers PM-1 Volume: 65 linear feet • Biographical Note • Chronology • Scope and Content • Series Descriptions • Box & Folder List Biographical Note John J. Marchi, the son of Louis and Alina Marchi, was born on May 20, 1921, in Staten Island, New York. He graduated from Manhattan College with first honors in 1942, later receiving a Juris Doctor from St. John’s University School of Law and Doctor of Judicial Science from Brooklyn Law School in 1953. He engaged in the general practice of law with offices on Staten Island and has lectured extensively to Italian jurists at the request of the State Department. Marchi served in the Coast Guard and Navy during World War II and was on combat duty in the Atlantic and Pacific theatres of war. Marchi also served as a Commander in the Active Reserve after the war, retiring from the service in 1982. John J. Marchi was first elected to the New York State Senate in the 1956 General Election. As a Senator, he quickly rose to influential Senate positions through the chairmanship of many standing and joint committees, including Chairman of the Senate Standing Committee on the City of New York. In 1966, he was elected as a Delegate to the Constitutional Convention and chaired the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Constitutional Issues. That same year, Senator Marchi was named Chairman of the New York State Joint Legislative Committee on Interstate Cooperation, the oldest joint legislative committee in the Legislature. Other senior state government leadership positions followed, and this focus on state government relations and the City of New York permeated Senator Marchi’s career for the next few decades. -

Theatre in England 2011-2012 Harlingford Hotel Phone: 011-442

English 252: Theatre in England 2011-2012 Harlingford Hotel Phone: 011-442-07-387-1551 61/63 Cartwright Gardens London, UK WC1H 9EL [*Optional events — seen by some] Wednesday December 28 *1:00 p.m. Beauties and Beasts. Retold by Carol Ann Duffy (Poet Laureate). Adapted by Tim Supple. Dir Melly Still. Design by Melly Still and Anna Fleischle. Lighting by Chris Davey. Composer and Music Director, Chris Davey. Sound design by Matt McKenzie. Cast: Justin Avoth, Michelle Bonnard, Jake Harders, Rhiannon Harper- Rafferty, Jack Tarlton, Jason Thorpe, Kelly Williams. Hampstead Theatre *7.30 p.m. Little Women: The Musical (2005). Dir. Nicola Samer. Musical Director Sarah Latto. Produced by Samuel Julyan. Book by Peter Layton. Music and Lyrics by Lionel Siegal. Design: Natalie Moggridge. Lighting: Mark Summers. Choreography Abigail Rosser. Music Arranger: Steve Edis. Dialect Coach: Maeve Diamond. Costume supervisor: Tori Jennings. Based on the book by Louisa May Alcott (1868). Cast: Charlotte Newton John (Jo March), Nicola Delaney (Marmee, Mrs. March), Claire Chambers (Meg), Laura Hope London (Beth), Caroline Rodgers (Amy), Anton Tweedale (Laurie [Teddy] Laurence), Liam Redican (Professor Bhaer), Glenn Lloyd (Seamus & Publisher’s Assistant), Jane Quinn (Miss Crocker), Myra Sands (Aunt March), Tom Feary-Campbell (John Brooke & Publisher). The Lost Theatre (Wandsworth, South London) Thursday December 29 *3:00 p.m. Ariel Dorfman. Death and the Maiden (1990). Dir. Peter McKintosh. Produced by Creative Management & Lyndi Adler. Cast: Thandie Newton (Paulina Salas), Tom Goodman-Hill (her husband Geraldo), Anthony Calf (the doctor who tortured her). [Dorfman is a Chilean playwright who writes about torture under General Pinochet and its aftermath. -

Cinema Programme October 2017

Special Screenings Coming Up At Junction NT LIVE: HAMLET (Encore) Thursday 5 October, 7pm All tickets £11 Academy Award nominee Benedict Cumberbatch takes on the title role of Shakespeare’s great tragedy. Now seen by over 750,000 people worldwide, the original 2015 NT Live Cinema Programme broadcast returns to cinemas. As a country arms itself for war, a family tears itself apart. Forced to avenge his father’s death but paralysed by the task ahead, Hamlet rages against the October 2017 impossibility of his predicament, threatening both his sanity and the security of the state. RSC LIVE: CORIOLANUS Wednesday 11 October, 7pm All tickets £11 A full-throttle war play, Coriolanus transports us back to the emergence of the republic of Rome. Coriolanus is a fearless soldier but a reluctant leader who struggles to do what is required to achieve greatness. In this new city state struggling to find its feet, where the gap between rich and poor is widening every day, Coriolanus must decide who he really is and where his allegiances lie. Rome Season Director, Angus Jackson, completes the RSC’s collection of Shakespeare’s Roman plays. NT LIVE: FOLLIES Thursday 16 November, 7pm All tickets £11 Stephen Sondheim’s legendary musical is staged for the first time at the National Theatre and broadcast live to cinemas. New York, 1971. There’s a party on the stage of the Weismann Theatre. Tomorrow the iconic building will be demolished. Thirty years after their final performance, the Follies girls gather to have a few drinks, sing a few songs and lie about themselves. -

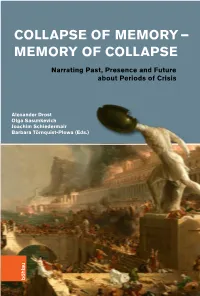

Collapse of Memory

– – COLLAPSE OF MEMORY – MEMORY OF COLLAPSE Narrating Past, Presence and Future about Periods of Crisis Alexander Drost Olga Sasunkevich Joachim Schiedermair COLLAPSE OF MEMORY OF COLLAPSE MEMORY Barbara Törnquist-Plewa (Eds.) Alexander Drost, Volha Olga Sasunkevich, Olga Sasunkevich, Alexander Drost, Volha Joachim Schiedermair, Barbara Törnquist-Plewa Joachim Schiedermair, Barbara Törnquist-Plewa Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC 4.0 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC 4.0 Alexander Drost ∙ Olga Sasunkevich Joachim Schiedermair ∙ Barbara Törnquist-Plewa (Ed.) COLLAPSE OF MEMORY – MEMORY OF COLLAPSE NARRATING PAST, PRESENCE AND FUTURE ABOUT PERIODS OF CRISIS BÖHLAU VERLAG WIEN KÖLN WEIMAR Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC 4.0 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft aus Mitteln des Internationalen Graduiertenkollegs 1540 „Baltic Borderlands: Shifting Boundaries of Mind and Culture in the Borderlands of the Baltic Sea Region“ Published with assistance of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft by funding of the International Research Training Group “Baltic Borderlands: Shifting Boundaries of Mind and Culture in the Borderlands of the Baltic Sea Region” Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek : Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie ; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © 2019 by Böhlau Verlag GmbH & Cie, Lindenstraße 14, D-50674 Köln -

2016 in Review ABOUT NLGJA

2016 In Review ABOUT NLGJA NLGJA – The Association of LGBTQ Journalists is the premier network of LGBTQ media professionals and those who support the highest journalistic standards in the coverage of LGBTQ issues. NLGJA provides its members with skill-building, educational programming and professional development opportunities. As the association of LGBTQ media professionals, we offer members the space to engage with other professionals for both career advancement and the chance to expand their personal networks. Through our commitment to fair and accurate LGBTQ coverage, NLGJA creates tools for journalists by journalists on how to cover the community and issues. NLGJA’s Goals • Enhance the professionalism, skills and career opportunities for LGBTQ journalists while equipping the LGBTQ community with tools and strategies for media access and accountability • Strengthen the identity, respect and status of LGBTQ journalists in the newsroom and throughout the practice of journalism • Advocate for the highest journalistic and ethical standards in the coverage of LGBTQ issues while holding news organizations accountable for their coverage • Collaborate with other professional journalist associations and promote the principles of inclusion and diversity within our ranks • Provide mentoring and leadership to future journalists and support LGBTQ and ally student journalists in order to develop the next generation of professional journalists committed to fair and accurate coverage 2 Introduction NLGJA 2016 In Review NLGJA 2016 In Review Table of