70806 for PDF 11/05

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 32 No. 1, Spring 2016

Features: Bartolomeo Campagnoli and His 41 Capricci An Afternoon at Skittles: On Playing Mozart’s “Kegelstatt” Trio Part I Volume 32 Number 1 Number 32 Volume Journal of the American ViolaSociety American the of Journal Viola V32 N1.indd 301 3/16/16 6:20 PM Viola V32 N1.indd 302 3/16/16 6:20 PM Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Spring 2016: Volume 32, Number 1 p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President News & Notes p. 7 Announcements Feature Articles p. 9 Bartolomeo Campagnoli and His 41 Capricci: The Ever-Changing Role of the Virtuosic Viola and Its Technique: Dalton Competition prize-winner Alicia Marie Valoti explores a history of the Campagnoli 41 Capricci and its impact on the progression of the viola’s reputation as a virtuosic instrument. p. 19 An Afternoon at Skittles: On Playing Mozart’s “Kegelstatt” Trio Part I: A Trio for Signora Dinimininimi, Nàtschibinìtschibi, and Pùnkitititi: Edward Klorman gives readers an interesting look into background on the Mozart “Kegelstatt” Trio. Departments p. 29 New Music: Michael Hall presents a number of exciting new works for viola. p. 35 Outreach: Janet Anthony and Carolyn Desroisers give an account of the positive impact that BLUME is having on music education in Haiti. p. 39 Retrospective: JAVS Associate Editor David M. Bynog writes about the earliest established viola ensemble in the United States. p. 45 Student Life: Zhangyi Chen describes how one of his choral compositions became the basis of a new viola concerto. p. -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 32 No. 1, Spring 2016

Features: Bartolomeo Campagnoli and His 41 Capricci An Afternoon at Skittles: On Playing Mozart’s “Kegelstatt” Trio Part I Volume 32 Number 1 Number 32 Volume Journal of the American ViolaSociety American the of Journal Viola V32 N1.indd 301 3/16/16 6:20 PM Viola V32 N1.indd 302 3/16/16 6:20 PM Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Spring 2016: Volume 32, Number 1 p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President News & Notes p. 7 Announcements Feature Articles p. 9 Bartolomeo Campagnoli and His 41 Capricci: The Ever-Changing Role of the Virtuosic Viola and Its Technique: Dalton Competition prize-winner Alicia Marie Valoti explores a history of the Campagnoli 41 Capricci and its impact on the progression of the viola’s reputation as a virtuosic instrument. p. 19 An Afternoon at Skittles: On Playing Mozart’s “Kegelstatt” Trio Part I: A Trio for Signora Dinimininimi, Nàtschibinìtschibi, and Pùnkitititi: Edward Klorman gives readers an interesting look into background on the Mozart “Kegelstatt” Trio. Departments p. 29 New Music: Michael Hall presents a number of exciting new works for viola. p. 35 Outreach: Janet Anthony and Carolyn Desroisers give an account of the positive impact that BLUME is having on music education in Haiti. p. 39 Retrospective: JAVS Associate Editor David M. Bynog writes about the earliest established viola ensemble in the United States. p. 45 Student Life: Zhangyi Chen describes how one of his choral compositions became the basis of a new viola concerto. p. -

The New York Chamber Music Society, 1915-1937: a Contribution to Wind Chamber Music and a Reflection of Concert Life in New York City in the Early 20Th Century

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2013 The New York Chamber Music Society, 1915-1937: A Contribution to Wind Chamber Music and a Reflection of Concert Life in New York City in the Early 20th Century Lisa Kozenko The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2557 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The New York Chamber Music Society, 1915-1937: A Contribution to Wind Chamber Music and a Reflection of Concert Life in New York City in the Early 20th Century by LISA A. KOZENKO A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2013 © 2013 Lisa A. Kozenko All rights reserved. This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Professor Jeffrey Taylor ___________________ ________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Professor David Olan ___________________ ________________________ Date Executive Officer Professor Richard Burke Professor Sylvia Kahan Professor Catherine Coppola Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK Abstract The New York Chamber Music Society, 1915-1937: A Contribution to Wind Chamber Music and a Reflection of Concert Life in New York City in the Early 20th Century by Lisa A. -

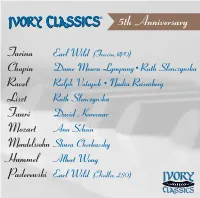

72010 Booklet

5th Anniversary Turina Earl Wild (Freccia, RPO) Chopin Dame Moura Lympany• Ruth Slenczynska Ravel Ralph Votapek • Nadia Reisenberg Liszt Ruth Slenczynska Fauré David Korevaar Mozart Ann Schein Mendelssohn Shura Cherkassky Hummel Albert Wong Paderewski Earl Wild (Fiedler, LSO) Ivory Classics 5th Anniversary Joaquin Turina (1882-1949) In Paris, October 1907, Turina had a fateful encounter with Falla and Albeniz, where he conceived his artistic credo “to fight bravely for the national music of our country.” He studied piano with Moszkowski and theory and composition with Vincent d’Indy in the Schola Cantorum. A fierce proponent of his native Andalusia, Turina was no less a formalist he was greatly influ- enced by the Schola Cantorum and the ‘cyclic’ experiments in music from Franck, d’Indy and Chausson. Turina wrote his Rapsodia sinfónica 1 in 1931, deliberately exploiting light tex- tures, piano and strings, somewhat in the manner of Liszt’s Malediction, where the piano and a solo violin have a concertante role. The piece is in two sections, the first a lushly scored Andante that segues to an Allegro vivo that imitates the rapid repeated notes and tremolo figurations from Spanish guitar music and “deep song.” The form is a rondena in 3/4 and 6/8, quickly alter- Joaquin Turina nating (using hemiola) to achieve, a bravura, the flavor of the Andalusian countryside. Earl Wild 1 & 15 is considered by many to be the last of the Romantic pianists and is internation- ally recognized as one of the great virtuoso pianist/composers of all time. Born on November 26, 1915, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Earl Wild’s technical accomplishments are often likened to what those of Liszt himself must have had. -

Strange Vibrations: the Evolution of the Theremin

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 5-2019 Strange Vibrations: The Evolution of the Theremin Kasey Mathew California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Mathew, Kasey, "Strange Vibrations: The Evolution of the Theremin" (2019). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 463. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all/463 This Capstone Project (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects and Master's Theses at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Strange Vibrations: The Evolution of the Theremin By Kasey Mathew Introduction Can you imagine an instrument which is played without physically touching it? Leon Theremin not only imagined it, he made it a reality. This project will examine the unusual and versatile instrument known as the theremin. It will look at the history and development of the instrument as well as the story of its Russian inventor, Leon Theremin, and notable performer Clara Rockmore. The physics behind the instrument will be briefly examined. Several prominent uses of the theremin in popular culture/media will be studied including its use in science fiction movies of the 1950s. Also examined will be the electro-theremin, a simplified version of the instrument which is used as a distinguishing feature of the 1966 music of the Beach Boys in "Good Vibrations." Additional instruments inspired by the theremin will be explored.