RECEIVED Marlene H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literariness.Org-Mareike-Jenner-Auth

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more pop- ular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Titles include: Maurizio Ascari A COUNTER-HISTORY OF CRIME FICTION Supernatural, Gothic, Sensational Pamela Bedore DIME NOVELS AND THE ROOTS OF AMERICAN DETECTIVE FICTION Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Clare Clarke LATE VICTORIAN CRIME FICTION IN THE SHADOWS OF SHERLOCK Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Michael Cook NARRATIVES OF ENCLOSURE IN DETECTIVE FICTION The Locked Room Mystery Michael Cook DETECTIVE FICTION AND THE GHOST STORY The Haunted Text Barry Forshaw DEATH IN A COLD CLIMATE A Guide to Scandinavian Crime Fiction Barry Forshaw BRITISH CRIME FILM Subverting -

Teaching Social Issues with Film

Teaching Social Issues with Film Teaching Social Issues with Film William Benedict Russell III University of Central Florida INFORMATION AGE PUBLISHING, INC. Charlotte, NC • www.infoagepub.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Russell, William B. Teaching social issues with film / William Benedict Russell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-60752-116-7 (pbk.) -- ISBN 978-1-60752-117-4 (hardcover) 1. Social sciences--Study and teaching (Secondary)--Audio-visual aids. 2. Social sciences--Study and teaching (Secondary)--Research. 3. Motion pictures in education. I. Title. H62.2.R86 2009 361.0071’2--dc22 2009024393 Copyright © 2009 Information Age Publishing Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America Contents Preface and Overview .......................................................................xiii Acknowledgments ............................................................................. xvii 1 Teaching with Film ................................................................................ 1 The Russell Model for Using Film ..................................................... 2 2 Legal Issues ............................................................................................ 7 3 Teaching Social Issues with Film -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Dairy Facts County

www.tooeletranscript.com TUESDAY TOOELE RANSCRIPT Classic pioneer T fashions on runway at grist mill jubilee See B1 BULLETIN June 13, 2006 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 113 NO. 6 50 cents Separate collisions claim two young men by Jesse Fruhwirth STAFF WRITER Two local men in their early 20s lost their lives this weekend in unrelated automobile crashes. Both occurred in the early morning hours Saturday. Law enforcement officials said it is not clear yet if alcohol was involved in either accident, but nei- ther man was wearing a seat belt. As a result both men were ejected from their vehicles. Stansbury Park resident Parker David Buck, 20, died shortly after the vehicle he was driving rolled several times and crashed into an embankment in Middle Canyon. Troy Sullivan, 21, of Tooele, was pronounced dead at the scene of his crash on Pine Canyon Road behind Westgate Theaters. His vehicle like- wise rolled after crashing into a cement barrier. Buck was a 2005 graduate of Tooele High School. Sullivan gradu- Photography / Mark Watson Motorcycle racers complete the first lap of a race Saturday afternoon at Miller Motorsports Park. The $5-million clubhouse is shown in the background. Saturday’s races ated from THS in 2003. were free to the public as part of grand opening activities. Both obituararies appear on A6. A relative explosion of motor- vehicle deaths have occurred since the summer season began. Six people have met violent deaths on Tooele’s roads since May 20. Crowds get green light at Miller park Motor vehicle traffic accidents are the leading cause of death by Mark Watson Tooele County officials and throughout the nation who continued, “It is an amazing on tours of the property which of American males age 15-24. -

JOE GALLAGHER Director of Photography ! REELS/WEBSITE

! JOE GALLAGHER Director of Photography ! REELS/WEBSITE Television & Film ! PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. BILLIONS (season 4, 1 ep. + season 6) Matthew McLoota Showtime EP: Brian Koppelman, David Levien, Andrew Ross Sorkin CHARMED (seasons 2-3) Various CW / CBS Television Studios EP: Craig Shapiro, Elizabeth Kruger PROVEN INNOCENT (season 1) Various Fox EP: David Elliot, Stacy Greenberg, Danny Strong CHAMBERS (season1, 1 ep.) Tony Goldwyn Netflix EP: Leah Rachel, Akela Cooper, Stephen Gaghan GET SHORTY (season 2) Various Epix / MGM Television EP: Davey Holmes, Adam Arkin, Dan Nowak REVERIE (season 1) Various NBC / Amblin Television EP: Mickey Fisher, Justin Falvey, Darryl Frank SALVATION (pilot) Various CBS / Secret Hideout EP: Alex Kurtzman, Heather Kadin, Peter Lenkov HAP AND LEONARD (season 2) Various Sundance / Nightshade EP: Jim Mickle, Nick Damici, Nick Shumaker MASTERS OF SEX (season 4) Various Showtime / Timberman/Beverly Productions EP: Michelle Ashford, Sarah Timberman, Colin Bucksey BLUNT TALK (pilot + series) Various Starz / Media Rights Capitol Prod: Jonathan Ames, Seth MacFarlane BOSCH (season 2) Various Amazon Studios / Fabrik Entertainment EP: Michael Connelly, Eric Overmyer, Pieter Jan Brugge MATADOR (pilot + series) Robert Rodriguez El Rey Network / Georgeville TV Prod: Alex Kurtzman, Roberto Orci THE GOLDBERGS (seasons 1-2) Various Happy Madison / Sony Pictures Television Prod: Seth Gordon, Adam Goldberg VEGAS (series) Various CBS Prod: James Mangold, Cathy Konrad RING OF FIRE (tv movie) Allison Anders Lifetime -

2010 Annual Report

2010 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Media Council Board of Governors ..............................................................................................................12 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA Events .................................................................................................................................14 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Robert M. -

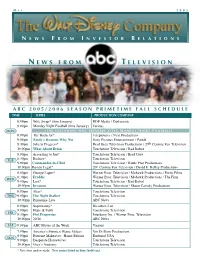

N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N

M A Y 2 0 0 5 N E W S F R O M I N V E S T O R R E L A T I O N S N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N A B C 2 0 0 5 / 2 0 0 6 S E A S O N P R I M E T I M E F A L L S C H E D U L E TIME SERIES PRODUCTION COMPANY 8:00pm Wife Swap* (thru January) RDF Media / Diplomatic 9:00pm Monday Night Football (thru January) Various MON ( T H E F O L L O W I N G W I L L P R E M I E R E A F T E R M O N D A Y N I G H T F O O T B A L L ) 8:00pm The Bachelor* Telepictures / Next Productions 9:00pm Emily’s Reasons Why Not Sony Pictures Entertainment / Pariah 9:30pm Jake in Progress* Brad Grey Television Productions / 20th Century Fox Television 10:00pm What About Brian Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 8:00pm According to Jim* Touchstone Television / Brad Grey 8:30pm Rodney* Touchstone Television TUE 9:00pm Commander-in-Chief Touchstone Television / Battle Plan Productions 10:00pm Boston Legal* 20th Century Fox Television / David E. Kelley Productions 8:00pm George Lopez* Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / Fortis Films 8:30pm Freddie Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / The Firm WED 9:00pm Lost* Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 10:00pm Invasion Warner Bros. -

Productions That Benefited from the Croatian Film Production Incentive

Productions that benefited from the Croatian film production incentive 2016. 2015. Star Wars: The Last Jedi Dig, season 1 (cont’d) The Odyssey Winnetou’s Wives Love Island directed by: Rian Johnson created by: Tim Kring and Gideon Raff directed by: Jérôme Salle directed by: Dirk Regel directed by: Jasmila Žbanić starring: Daisy Ridley, John Boyega, Mark starring: Jason Isaacs, Anne Heche, Alison starring: Lambert Wilson, Audrey Tautou, starring: Maren Kroymann, Floriane Daniel, starring: Ariane Labed, Ada Condeescu, Hamill, Laura Dern, Benicio Del Toro Sudol, Ori Pfeffer and Davzid Costabile. Pierre Niney Nina Kronjager, Josephin Busch and Teresa Ermin Bravo, Franco Nero and Leon Lučev produced by: Lucasfilm, Ram Bergman produced by: NBC Universal produced by: Fidélité Films and Pan- Wessbach produced by: Produkcija Živa, Komplizen Productions and Walt Disney Pictures Européenne produced by: UFA Fiction Film, Okofilm Production Fan Three Heists and a Hamster directed by: Maneesh Sharma Der kroatien krimi, 2-part Game of Thrones, Season 5 Itsi Bitsi directed by: Rasmus Heide starring: Shahrukh Khan, Sayani Gupta, tv film created by: David Benioff and D.B. Weiss directed by: Ole Christian Madsen starring:: Mick Øgendahl, Rasmus Bjerg, Atul Sharma starring: Kit Harrington, Emilia Clarke, starring: Joachim Fjelstrup and Marie directed by: Michael Kreindl Zlatko Burić, Sonja Richter produced by: Yash Raj Films Peter Dinklage, Lena Headey, Sophie Turner, Tourell Soderberg starring: Neda Rahmanian, Lenn produced by: Fridthjof Film Maisie Williams, -

Crime, Class, and Labour in David Simon's Baltimore

"From here to the rest of the world": Crime, class, and labour in David Simon's Baltimore. Sheamus Sweeney B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) This thesis is submitted to Dublin City University for the award of Ph.D in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. August 2013 School of Communications Supervisors: Prof. Helena Sheehan and Dr. Pat Brereton I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Ph.D is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ___________________________________ (Candidate) ID No.: _55139426____ Date: _______________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Literature review and methodology 17 Chapter One: Stand around and watch: David Simon and the 42 "cop shop" narrative. Chapter Two: "Let the roughness show": From death on the 64 streets to a half-life on screen. Chapter Three: "Don't give the viewer the satisfaction": 86 Investigating the social order in Homicide. Chapter Four: Wasteland of the free: Images of labour in the 122 alternative economy. Chapter Five: The Wire: Introducing the other America. 157 Chapter Six: Baltimore Utopia? The limits of reform in the 186 war on labour and the war on drugs. Chapter Seven: There is no alternative: Unencumbered capitalism 216 and the war on drugs. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. JA Jason Aldean=American singer=188,534=33 Julia Alexandratou=Model, singer and actress=129,945=69 Jin Akanishi=Singer-songwriter, actor, voice actor, Julie Anne+San+Jose=Filipino actress and radio host=31,926=197 singer=67,087=129 John Abraham=Film actor=118,346=54 Julie Andrews=Actress, singer, author=55,954=162 Jensen Ackles=American actor=453,578=10 Julie Adams=American actress=54,598=166 Jonas Armstrong=Irish, Actor=20,732=288 Jenny Agutter=British film and television actress=72,810=122 COMPLETEandLEFT Jessica Alba=actress=893,599=3 JA,Jack Anderson Jaimie Alexander=Actress=59,371=151 JA,James Agee June Allyson=Actress=28,006=290 JA,James Arness Jennifer Aniston=American actress=1,005,243=2 JA,Jane Austen Julia Ann=American pornographic actress=47,874=184 JA,Jean Arthur Judy Ann+Santos=Filipino, Actress=39,619=212 JA,Jennifer Aniston Jean Arthur=Actress=45,356=192 JA,Jessica Alba JA,Joan Van Ark Jane Asher=Actress, author=53,663=168 …….. JA,Joan of Arc José González JA,John Adams Janelle Monáe JA,John Amos Joseph Arthur JA,John Astin James Arthur JA,John James Audubon Jann Arden JA,John Quincy Adams Jessica Andrews JA,Jon Anderson John Anderson JA,Julie Andrews Jefferson Airplane JA,June Allyson Jane's Addiction Jacob ,Abbott ,Author ,Franconia Stories Jim ,Abbott ,Baseball ,One-handed MLB pitcher John ,Abbott ,Actor ,The Woman in White John ,Abbott ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Canada, 1891-93 James ,Abdnor ,Politician ,US Senator from South Dakota, 1981-87 John ,Abizaid ,Military ,C-in-C, US Central Command, 2003- -

Desperate Housewives

Desperate Housewives Titre original Desperate Housewives Autres titres francophones Beautés désespérées Genre Comédie dramatique Créateur(s) Marc Cherry Musique Steve Jablonsky, Danny Elfman (2 épisodes) Pays d’origine États-Unis Chaîne d’origine ABC Nombre de saisons 5 Nombre d’épisodes 108 Durée 42 minutes Diffusion d’origine 3 octobre 2004 – en production (arrêt prévu en 2013)1 Desperate Housewives ou Beautés désespérées2 (Desperate Housewives en version originale) est un feuilleton télévisé américain créé par Charles Pratt Jr. et Marc Cherry et diffusé depuis le 3 octobre 2004 sur le réseau ABC. En Europe, le feuilleton est diffusé depuis le 8 septembre 2005 sur Canal+ (France), le 19 mai sur TSR1 (Suisse) et le 23 mai 2006 sur M6. En Belgique, la première saison a été diffusée à partir de novembre 2005 sur RTL-TVI puis BeTV a repris la série en proposant les épisodes inédits en avant-première (et avec quelques mois d'avance sur RTL-TVI saison 2, premier épisode le 12 novembre 2006). Depuis, les diffusions se suivent sur chaque chaîne francophone, (cf chaque saison pour voir les différentes diffusions : Liste des épisodes de Desperate Housewives). 1 Desperate Housewives jusqu'en 2013 ! 2La traduction littérale aurait pu être Ménagères désespérées ou littéralement Épouses au foyer désespérées. Synopsis Ce feuilleton met en scène le quotidien mouvementé de plusieurs femmes (parfois gagnées par le bovarysme). Susan Mayer, Lynette Scavo, Bree Van De Kamp, Gabrielle Solis, Edie Britt et depuis la Saison 4, Katherine Mayfair vivent dans la même ville Fairview, dans la rue Wisteria Lane. À travers le nom de cette ville se dégage le stéréotype parfaitement reconnaissable des banlieues proprettes des grandes villes américaines (celles des quartiers résidentiels des wasp ou de la middle class). -

Billy Burkhalter: the Maltese Man: a Video Game for Wimps

Billy Burkhalter: The Maltese Man: A Video Game for Wimps Project Paper for CC8096 Communication & Culture: Master's Project Joint Programme in Communication & Culture Ryerson University I York University Sean Springer September 24, 2004 - Table of Contents Acknowledgements .............................................................................. 1 Video Games and Masculinity in the Twenty-First Century ............................ 2 An Alternative Model ........................................................................... 10 Conclusion: Production of the Test Scene ................................................ 28 References ....................................................................................... 30 Notes ............................................................................................... 32 "The Big Lebowski: A Mass-Produced Fantasy for Wimps" .............. Appendix A Plot Outline of Billy Burkhalter: The Maltese Man .......................... Appendix B Flash Postings ..................................................................... Appendix C Script for Billy Burkhalter: The Maltese Man ................................. Appendix D Sketches of the Main Characters ............................................... Appendix E ETER $' Springer Project Paper, Third Draft "Billy Burkhalter, the Maltese Man: A Video Game for Wimps" Page 1 Acknowledgments Billy Burkhalter, the Maltese Man would not have been possible had it not for the help and support of the following people and organizations (in alphabetical