Classical Hebrew Poetry a Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

The Migrant Surge and the Border Mess

EARNING YOUR TRUST, EVERY DAY. 04.24.21 VOLUME 36 NUMBER 8 THE “IT JUST FEELS NICE AFTER A YEAR OF THIS. … WE’RE ALMOST THROUGH.” —EMERGING FROM A PANDEMIC, P. 38 P. PANDEMIC, A FROM —EMERGING THROUGH.” ALMOST WE’RE … THIS. OF AFTER YEAR NICE A FEELS JUST “IT MIGRANT SURGE AND THE BORDER MESS P. 44 FEATURES 04.24.21 VOLUME 36 NUMBER 8 58 REFUGEES’ GAMBIT Top chess players from Iran are seeking asylum elsewhere, following a long history of chess talent using international events to escape persecution at home by Emily Belz 38 44 52 HOPE AFTER A PANDEMIC BORDER BACKTRACKING COURTING CHRISTIANS Following a year of coronavirus The U.S.-Mexico border isn’t open, In Israel’s battle to form a coalition lockdowns, illness, and death, but a migrant surge and a mishmash government, the spotlight turns to Americans rejoice at a vaccine and of messages and policies ethnic Aramean Christians long little steps back to normal living have created another crisis overlooked by Jewish politicians by WORLD reporters by Sophia Lee by Mindy Belz HOLLIE ADAMS/GETTY IMAGES 04.24.21 WORLD DEPARTMENTS 04.24.21 VOLUME 36 NUMBER 8 5 MAILBAG 6 NOTES FROM THE CEO 68 A scene from the Netflix Korean drama series Crash Landing on You Dispatches Culture Notebook 11 NEWS ANALYSIS 21 MOVIES & TV 65 EDUCATION Major League Baseball’s The Falcon and the VIEWERS foray into voting law Winter Soldier, The Map 67 LIFESTYLE debates of Tiny Perfect Things, CONNECT TO Roe v. Wade, Sound of 68 MEDIA 13 BY THE NUMBERS Metal, The Professor K-DRAMA Broadcasting clean, and the Madman romantic fun, K-drama 14 HUMAN RACE EMOTIONALLY grows in popularity in 26 BOOKS EVEN IF the United States 15 QUOTABLES 28 CHILDREN’S BOOKS THEY DON’T 16 QUICK TAKES Voices 30 Q&A UNDERSTAND Ze’ev Chafets 8 Joel Belz IT ALL. -

Right Arm Resource Update

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 7/8/2020 Semisonic “You’re Not Alone” The first single from their You’re Not Alone EP, out 9/18 BDS Monitored #1 Most Added before add week! Early: KCMP, KCSN, WRNR, WXPK, WFUV, WTMD, WFPK, KTBG, Music Choice, WPYA, WOCM, KYSL, WFIV, WJCU, KNBA, KSLU, WUKY, WOXL This is their first new music in almost 20 years Tons of great press “Like their greatest hits of yesteryear” - Consequence of Sound Margo Price “Letting Me Down” The first single That’s How Rumors Get Started, produced by Sturgill Simpson, out this Friday Appeared on CBS This Morning BDS Monitored New & Active, JBE Tracks 49*, Public 23*! New: WEVL ON: WRLT, WFUV, WXPN, Music Choice, WYEP, WFPK, WTMD, KTBG, KJAC, WRSI and more Tons of recent and upcoming press Watch the creative video on my site now Buzzard Buzzard Buzzard “Double Denim Hop” The first single from The Non-Stop EP, out this Friday New: WCNR, WYCE ON: KCSN, KJAC, WCLX, WCBE, WBJB, WOCM, WFIV, KROK “Think Thin Lizzy or T-Rex in the back room of a pub, riffs and tunes intact but with an endearing slacker attitude.” - The Guardian Great UK press! Topping the Alt Press list of the Best New British Guitar-Rock Bands: “Theirs is the ground floor to be on, friends.” Joshua Speers “Bad Night” From his Human Now EP, out now New: WYCE, KROK, WCBE, KSLU ON: KSMF, KCLC, WFIV, KUWR “The five-track project is such an enamoring listen, kind of perfect for quarantine, whether with a cup of coffee—or whiskey.. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

Augsome Karaoke Song List Page 1

AUGSome Karaoke Song List 44 - When Your Heart Stops Beating 112 - Come See Me 112 - Cupid 112 - Dance With Me 112 - It's Over Now 112 - Only You 112 - Peaches And Cream 112 - U Already Know 311 - All Mixed Up 311 - Amber 311 - Beyond The Gray Sky 311 - Creatures (For A While) 311 - Don't Tread On Me 311 - Down 311 - First Straw 311 - Hey You 311 - I'll Be Here Awhile 311 - Love Song 311 - You Wouldn't Believe 411 - Dumb 411 - On My Knees 411 - Teardrops 702 - Get It Together 702 - I Still Love You 702 - Steelo 702 - Where My Girls At 911 - All I Want Is You 911 - How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 - Little Bit More, A 911 - More Than A Woman 911 - Party People (Friday Night) 911 - Private Number 1927 - That's When I Think Of You 1975 - Chocolate 1975 - City 1975 - Love Me 1975 - Robbers 1975 - Sex 1975 - Sound 1975 - Ugh 1 Giant Leap And Jazz Maxi - My Culture 10 Years - Beautiful 10 Years - Through The Iris 10 Years - Wasteland 10,000 Maniacs - Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs - Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs - Like The Weather 10,000 Maniacs - More Than This 10,000 Maniacs - These Are The Days 10,000 Maniacs - Trouble Me 100 Proof Aged In Soul - Somebody's Been Sleeping Page 1 AUGSome Karaoke Song List 101 Dalmations - Cruella de Vil 10Cc - Donna 10Cc - Dreadlock Holiday 10Cc - I'm Mandy 10Cc - I'm Not In Love 10Cc - Rubber Bullets 10Cc - Things We Do For Love, The 10Cc - Wall Street Shuffle 112 And Ludacris - Hot And Wet 12 Gauge - Dunkie Butt 12 Stones - Crash 12 Stones - We Are One 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

David Ramirez My Love Is a Hurricane

David Ramirez My Love Is A Hurricane How do you write love songs when your heart is broken? How do you sing about hope and passion when yours is lost? How do you finish an album when the relationship that inspired it has ended? During the Summer of 2017, David Ramirez had fallen in love with a woman who, despite having only just met, felt incredibly familiar to him. There was a scary but comfortable feeling of deja vu within their moments together. “In past relationships, no matter how eager I was to feel loved and to give love, there had always been a hesitation to crawl out of my old life. I didn’t feel this with her,” he recollects. Ramirez began to pen songs for his next album and hopeful odes to new love spilled out. Songs like “Lover, Will You Lead Me?” filled with vivid images from the heart: I recognized you from some distant dream / Like when it rains on a cold day / I had a chill in my bones / Is it true what they say / “When you know, you know.” These were followed by sultry, romantic ballads about how love matures and grows. He wrote “I Wanna Live In Your Bedroom” while sitting on his lover’s bed just minutes after waking up on a hazy fall day. “I was looking around at all the perfectly curated pieces in her room,” he says. “Everything was so intentional and held a story and a place in her heart. I wanted to be one of those pieces.” One after another, Ramirez poured his soul into a new work of art that covered both the sweet parts of love and the hard times it can bring. -

To Download The

10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 10cc Donna Dreadlock Holiday Good Morning Judge I'm Mandy, Fly Me I'm Not In Love Life Is A Minestrone One-Two-Five People In Love Rubber Bullets The Things We Do For Love The Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1975, The Chocolate Love Me Robbers Sex Somebody Else The City The Sound TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME UGH! 2 Chainz ft Wiz Khalifa We Own It 2 Eivissa Oh La La La 2 In A Room Wiggle It 2 Play ft Thomas Jules & Jucxi D Careless Whisper 2 Unlimited No Limit Twilight Zone 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 24KGoldn ft Iann Dior Mood 2Pac ft Dr. Dre UPDATED: 28/08/21 Page 1 www.kjkaraoke.co.uk California Love 2Pac ft Elton John Ghetto Gospel 3 Days Grace Just Like You 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Here Without You 3 Of A Kind Baby Cakes 3 Of Hearts The Christmas Shoes 30 Seconds To Mars Kings & Queens Rescue Me The Kill (Bury Me) 311 First Straw 38 Special Caught Up In You 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 3OH!3 ft Katy Perry Starstrukk 3OH!3 ft Ke$ha My First Kiss 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T ft Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up What's Up (Acoustic) 411, The Dumb UPDATED: 28/08/21 Page 2 www.kjkaraoke.co.uk On My Knees Teardrops 5 Seconds Of Summer Amnesia Don't Stop Girls Talk Boys Good Girls Jet Black Heart She Looks So Perfect She's Kinda Hot Teeth Youngblood 50 Cent Candy Shop In Da Club Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent ft Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent ft Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 50 Cent ft Nate Dogg 21 Questions 50 Cent ft Ne-Yo Baby By Me 50 Cent ft Snoop Dogg & -

BOYZONE Til Danmark 4. August

2011-03-24 09:50 CET BOYZONE til Danmark 4. august Eneste koncert i Danmark ved Skovrock i Aalborg BOYZONE, verdens næststørste boyband, og et af de bedst sælgende irske bands overhovedet, giver torsdag d. 4. aug. en exclusiv koncert i Skovdalen i Aalborg. Alle de største danske navne, og mange udenlandske topnavne som bl.a. Johnny Cash, Bonnie Raitt, Willie Nelson, Runrig og Brian Wilson har tidligere stået på Danmarks største faste udendørs scene i Skovdalen. Men torsdag d. 4. aug. er der lagt op til det hidtil største scoop, når BOYZONE som det eneste sted i Danmark giver koncert i Skovdalen som et led i deres stort anlagte "Brother Tour". Turneen følger op på deres album "Brother" fra sidste år, der er en hyldest til det afdøde bandmedlem Stephen Gately, der pludselig døde i oktober 2009. I februar og marts har Boyzone turneret i England og Irland, en tur der bl.a. har fyldt så store steder som "Wembley Arena" og "The O2" i London, og som har givet fantastiske anmeldelser til de 4 medlemmer Ronan Keating, Mikey Graham, Keith Duffy og Shane Lynch og deres stort anlagte shows. Boyzone har siden starten i 1993 skabt utallige hits, bl.a. ikke færre end 6 nummer 1 hits i UK og 9 nr. 1 hits i Irland. Og sætlisten fra koncerterne i London lover særdeles godt. Flere af bandets medlemmer har sideløbende med Boyzone solokarrierer kørende. Med størst succes Ronan Keating, der var vært for Eurovision Song Contest 1998, hvor Boyzone også optrådte. I 2009 vandt han Dansk Melodi Grand Prix med "Believe Again" sunget af Brinck. -

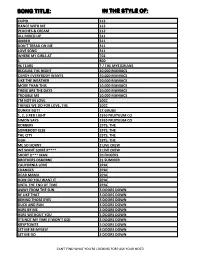

Song Title: in the Style Of

SONG TITLE: IN THE STYLE OF: CUPID 112 DANCE WITH ME 112 PEACHES & CREAM 112 ALL MIXED UP 311 AMBER 311 DON'T TREAD ON ME 311 LOVE SONG 311 WHERE MY GIRLS AT 702 1 800 96 TEARS ? / THE MYSTERIANS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 10,000 MANIACS CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 10,000 MANIACS LIKE THE WEATHER 10,000 MANIACS MORE THAN THIS 10,000 MANIACS THESE ARE THE DAYS 10,000 MANIACS TROUBLE ME 10,000 MANIACS I'M NOT IN LOVE 10CC THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE 10CC DUNKIE BUTT 12 GAUGE 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 1910 FRUITGUM CO SIMON SAYS 1910 FRUITGUM CO ROBBERS 1975, THE SOMEBODY ELSE 1975, THE THE CITY 1975, THE UGH 1975, THE ME SO HORNY 2 LIVE CREW WE WANT SOME P**** 2 LIVE CREW SHORT D*** MAN 20 FINGERS BROTHERS OSBORNE 21 SUMMER CALIFORNIA LOVE 2PAC CHANGES 2PAC DEAR MAMA 2PAC HOW DO YOU WANT IT 2PAC UNTIL THE END OF TIME 2PAC AWAY FROM THE SUN 3 DOORS DOWN BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN BEHIND THOSE EYES 3 DOORS DOWN DUCK AND RUN 3 DOORS DOWN HERE BY ME 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU 3 DOORS DOWN IT'S NOT MY TIME (I WON'T GO) 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 3 DOORS DOWN LET ME BE MYSELF 3 DOORS DOWN LET ME GO 3 DOORS DOWN CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? ASK YOUR HOST! SONG TITLE: IN THE STYLE OF: LIVE FOR TODAY 3 DOORS DOWN LOSER 3 DOORS DOWN ROAD I'M ON, THE 3 DOORS DOWN WHEN I'M GONE 3 DOORS DOWN LANDING IN LONDON 3 DOORS DOWN / BOB SEGER KILL (BURY ME), THE 30 SECONDS TO MARS CAUGHT UP IN YOU 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 38 SPECIAL ROCKIN' INTO THE NIGHT 38 SPECIAL SECOND CHANCE 38 SPECIAL TEACHER, TEACHER 38 SPECIAL WILD-EYED SOUTHERN BOYS 38 SPECIAL NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 3LW DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 MY FIRST KISS 3OH!3 / KESHA ANYTHING 3T BASICS OF LIFE, THE 4 HIM FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS 4 HIM WHAT'S UP 4 NON BLONDES SUKIYAKI 4 P.M. -

Brian Molko's

lifestyle WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 6, 2017 GOSSIP Hetfield recovers quickly from tumble at Amsterdam gig etallica's James Hetfield took a tumble on stage at not so much. But, we are fine. It hurt my feelings a maybe, record will feature unreleased material including demos, the band's show in Amsterdam on Monday night. a little bit. But I can tell you about it now it's done." The gui- rough mixes, videos and live tracks, including a new ver- MThe 'Seek & Destroy' rocker narrowly avoided a tar god and vocalist then bravely carried on with the rest of sion of 'Disposable Heroes' and a live recording of 'The serious injury after stepping backwards into a hole in the their 18-song set including an encore of 'Blackened', Thing That Should Not Be'. The LP was the band's first stage near to the drum kit at Ziggo Dome. Video footage "Nothing Else Matters' and Enter Sandman'. Metallica are record to go platinum and ended up going 6 x platinum in showed the 54-year-old singer fall down and pause for a currently on the European leg of their 'WorldWired' tour, the US. 'Master Of Puppets' was the last studio release the moment in pain as the band performed 'Now That We're which comes to London's The O2 on October 22 and 24 band recorded with late bass player Cliff Burton, who was Dead'. In the clip shared on YouTube by a fan, James asks and concludes at Birmingham's Genting Arena on October in the band from 1982 until his death in September 1986. -

Many Great Plays Have Been Adapted for the Silver Screen

J e f f e r s o n P e r f o r m i n g A r t s S o c i e t y Presents JEFFERSON PERFORMING ARTS SOCIETY 1118 Clearview Parkway Metairie, Louisiana 70001 Phone: 504 885 2000..Fax: 504 885 [email protected] 1 Table of Contents Teacher notes…………….4 Educational Overview……………………..6 History………………………………..7 – 15 Introduction…………………………..16 – 20 More Background…………………......21 - 49 Lesson Plans 1) “1940 - 1960’s: War Years, Rebuilding the World and a Leisure Boom” pg. 50 - 53 2) “Activities, Projects and Drama Exercises” pgs. 54 - 56 3) “A Hard Day’s Night” pgs. 57 - 64 Standards and Benchmarks: English……………….65 – 67 Standards and Benchmarks: Theatre Arts…………68 - 70 5) “The History of Rock and Roll” pgs. 71 - 73 6) “Bang on a Can: The Science of Music” pg. 74 Standards and Benchmarks: Music………………… 75 - 76 Photo gallery pgs. 77-80 2 Web Resource list …………..81 An early incarnation of the Beatles. Michael Ochs Archives, Venice, Calif. IMAGES RETRIEVED FROM: The Beatles, with George Martin of EMI Records, are presented with a silver disc to mark sales of over a quarter million copies of the 1963 British single release of "Please Please Me." Hulton Getty/Liaison Agency Image Retrieved From: http://search.eb.com/britishinvasion/obrinvs048p1.html http://search.eb.com/britishinvasion/obrinvs045p1.html 3 Teacher notes Welcome to the JPAS production of Yeah, Yeah, Yeah! a concert celebration performed by Pre-Fab 4, Featuring the stars of The Buddy Holly Story. Come together as four lads from across the US rekindle the spirit of yesterday through the music of the world’s most popular band. -

':'Roads:Lde .74 the NATIONAL TOPICAL SONG MAGAZINE Septel.Ffier 1966 PRICE -- • ,O¢

::':'roads:lde .74 THE NATIONAL TOPICAL SONG MAGAZINE SEPTEl.ffiER 1966 PRICE -- • ,O¢ I N THIS ISSUE ***it*** t'Wo songs by Pete Seeger ddBIG MUDDY" & FT. HOOD 3 ******* MAHOGANY ROW Ernie Marrs ******* Phil Ochs' CRUCIFIXION ******* Matt M·e Ginn *** Alex Cohen ******* MARY WALlJNG SINGS OF HER "NE\'iPOR'l'" BLUES ******* POETRY BY JEAN BATTLO LONESOl1E EXITER RUBEN TATRO ******* Tom Paxton's Talking "God Is Dead" Blues - 2 - Wordll! &: }msio: MA'l"r McGINN THE FOREMAN @ 1964 by Appleseed Music Mournfully Verse 'tn A'ff1, May-be I should nae be tel1in' this tale, But I'll tell it to ye just the same. I l I . CHO: l)1YI j '7/ .~ j I I a i, I., I J i&. I~J. I ,l. ( j J Jlj, ------I ..J J Heuch, Aye, Heuch till I fall; Heuch, Aye, Heuch till I dee (die). Onee I had a gatter* ; his name was O! Rourke I was trem.bl:!.n I with tear as his head gave. a thud He had a terrible passion tor his work; An I I looked down &: saw that his clothes were all md In miles and in tons he took all he could see Yet it waSIl It his clothes was the worst of his plight Though he \la8 never greedy, he gave lit to me. -- For his bead was jammed in there - a sorrowf'uJ. (* gaUer: boss) sight 1 . One 007 during work I went I roond for a smoke I looked &: I thought, as I buckled M'3' belt When the door burst open and there was O'Rourke; And yeW never could leal the compassion I fell:.; He started to swear and he gave me his curse 1II'1l was all his cl.othes,"were the words .that I said He insulted me mother, and that was far worse.