Religion and Community, Conflict and Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bristol Open Doors Day Guide 2017

BRING ON BRISTOL’S BIGGEST BOLDEST FREE FESTIVAL EXPLORE THE CITY 7-10 SEPTEMBER 2017 WWW.BRISTOLDOORSOPENDAY.ORG.UK PRODUCED BY WELCOME PLANNING YOUR VISIT Welcome to Bristol’s annual celebration of This year our expanded festival takes place over four days, across all areas of the city. architecture, history and culture. Explore fascinating Not everything is available every day but there are a wide variety of venues and activities buildings, join guided tours, listen to inspiring talks, to choose from, whether you want to spend a morning browsing or plan a weekend and enjoy a range of creative events and activities, expedition. Please take some time to read the brochure, note the various opening times, completely free of charge. review any safety restrictions, and check which venues require pre-booking. Bristol Doors Open Days is supported by Historic England and National Lottery players through the BOOKING TICKETS Heritage Lottery Fund. It is presented in association Many of our venues are available to drop in, but for some you will need to book in advance. with Heritage Open Days, England’s largest heritage To book free tickets for venues that require pre-booking please go to our website. We are festival, which attracts over 3 million visitors unable to take bookings by telephone or email. Help with accessing the internet is available nationwide. Since 2014 Bristol Doors Open Days has from your local library, Tourist Information Centre or the Architecture Centre during gallery been co-ordinated by the Architecture Centre, an opening hours. independent charitable organisation that inspires, Ticket link: www.bristoldoorsopenday.org.uk informs and involves people in shaping better buildings and places. -

Globe 140611

June 2011 INSIDE Who’s keeping an eye on College Green? The Memory Shed all our histories Music in Exile A taste of England Welcome to my home My favourite food… Kenya comes to Bristol Faith in the City Bristol City of Sanctuary Steering Committee Bristol City of Sanctuary Supporters CONTENTS June Burrough (Chair) Founder and Director, The Pierian Centre Co If your organisation would like to be Hotwells Primary School ng 3 Letter to Bristol ratula added this lists, please visit Imayla International Organisation tions Lorraine Ayensu Team Manager, Asylum Support and Refugee In - www.cityofsanctuary.org/bristol for Migration Inderjit Bhogal tegration Team, Bristol City Council Churches Council for Industry and Alistair Beattie Chief Executive, Faithnetsouthwest ACTA Community Theatre Social Responsibility 4 Editorial Caroline Beatty Co-ordinator, The Welcome Centre, Bristol African and Caribbean Chamber of John Wesley’s Chapel Mike Jempson to Bris Commerce and Enterprise Kalahari Moon to Refugee Rights l – Jo Benefield Bristol Defend Asylum Campaign African Initiatives Kenya Association in Bristol 5 A movement gaining ground Adam Cutler Bristol Central Libraries African Voices Forum Kingswood Methodist Church Stan Hazell Afrika Eye Malcom X Centre Mohammed Elsharif Secretary, Sudanese Association Amnesty International Bristol MDC Bristol Elinor Harris Area Manager, Refugee Action, Bristol p 6-7 The Memory Shed ro Group Methodist Church, South West ud to b Reverend Canon Tim Higgins The City Canon, Bristol Cathedral Eugene Byrne e Anglo-Iranian -

Schedule 1 Updated Jan 22

SCHEDULE 1 Sites 1 – 226 below are those where nuisance behaviour that relates to the byelaws had been reported (2013). These are the original sites proposed to be covered by the byelaws in the earlier consultation 2013. 1 Albany Green Park, Lower Cheltenham Place, Ashley, Bristol 2 Allison Avenue Amenity Area, Allison Avenue, Brislington East, Bristol 3 Argyle Place Park, Argyle Place, Clifton, Bristol 4 Arnall Drive Open Space, Arnall Drive, Henbury, Bristol 5 Arnos Court Park, Bath Road, , Bristol 6 Ashley Street Park, Conduit Place, Ashley, Bristol 7 Ashton Court Estate, Clanage Road, , Bristol 8 Ashton Vale Playing Fields, Ashton Drive, Bedminster, Bristol 9 Avonmouth Park, Avonmouth Road, Avonmouth, Bristol 10 Badocks Wood, Doncaster Road, , Bristol 11 Barnard Park, Crow Lane, Henbury, Bristol 12 Barton Hill Road A/A, Barton Hill Road, Lawrence Hill, Bristol 13 Bedminster Common Open Space, Bishopsworth, Bristol 14 Begbrook Green Park, Frenchay Park Road, Frome Val e, Bristol 15 Blaise Castle Estate, Bristol 16 Bonnington Walk Playing Fields, Bonnington Walk, , Bristol 17 Bower Ashton Playing Field, Clanage Road, Southville, Bristol 18 Bradeston Grove & Sterncourt Road, Sterncourt Road, Frome Vale, Bristol 19 Brandon Hill Park, Charlotte Street, Cabot, Bristol 20 Bridgwater Road Amenity Area, Bridgwater Road, Bishopsworth, Bristol 21 Briery Leaze Road Open Space, Briery Leaze Road, Hengrove, Bristol 22 Bristol/Bath Cycle Path (Central), Barrow Road, Bristol 23 Bristol/Bath Cycle Path (East), New Station Way, , Bristol 24 Broadwalk -

Wells Cathedral Library and Archives

GB 1100 Archives Wells Cathedral Library and Archives This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NR A 43650 The National Archives Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) WELLS CATHEDRAL LIBRARY READERS' HANDLIST to the ARCHIVES of WELLS CATHEDRAL comprising Archives of CHAPTER Archives of the VICARS CHORAL Archives of the WELLS ALMSHOUSES Library PICTURES & RE ALIA 1 Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) CONTENTS Page Abbreviations Archives of CHAPTER 1-46 Archives of the VICARS CHORAL 47-57 Archives of the WELLS ALMSHOUSES 58-64 Library PICTURES 65-72 Library RE ALIA 73-81 2 Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) ABBREVIATIONS etc. HM C Wells Historical Manuscripts Commission, Calendar ofManuscripts ofthe Dean and Chapter of Wells, vols i, ii (1907), (1914) LSC Linzee S.Colchester, Asst. Librarian and Archivist 1976-89 RSB R.S.Bate, who worked in Wells Cathedral Library 1935-40 SRO Somerset Record Office 3 Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) ARCHIVES of CHAPTER Pages Catalogues & Indexes 3 Cartularies 4 Charters 5 Statutes &c. 6 Chapter Act Books 7 Chapter Minute Books 9 Chapter Clerk's Office 9 Chapter Administration 10 Appointments, resignations, stall lists etc. 12 Services 12 Liturgical procedure 13 Registers 14 Chapter and Vicars Choral 14 Fabric 14 Architect's Reports 16 Plans and drawings 16 Accounts: Communar, Fabric, Escheator 17 Account Books, Private 24 Accounts Department (Modern) 25 Estates: Surveys, Commonwealth Survey 26 Ledger Books, Record Books 26 Manorial Court records etc. -

Bristol Office Locator

Office Locator KPMG LLP (UK) 66 Queen Square, Bristol BS1 4BE Switchboard: 0117 905 4200 M4 Junction 19 Pupert St Bristol Marriott Perry Rd Visiting or travelling to Bristol Bristol Bierkeller Hotel City Centre A420 Castle Park Park Row Broad St Car Small St A4044 M4 Junction 19, exit onto M32 towards Bristol Colston Hall O2 Academy Bristol Bristol M32 Parkway Continue onto Newfoundland St/A4032 Bristol Hippodrome Baldwin St Old Bread St Theatre Temple Back Continue to follow A4032 The Fleece Slight left onto Temple Way/A4044 Victoria St Continue to follow A4044 King St At the roundabout, take the 2nd exit onto TempleWay Bristol Aquarium Temple Gate/A4 Prince St Queen Square At-Bristol Science Centre At the roundabout, take the 4th exit and Welesh Back tS ffilcdeR tS Waterfront Redcliffe Way stay on Temple Gate/A4 The Grove Square Bristol Templetemple Meads Thekla Continue straight onto Redcliffe Way/A4044 Redcliffe Way Temple Gate At the roundabout, take the 2nd exit onto St Mary Redcliffe Church River Avon Redcliffe Way M Shed Rd Wapping Guinea St At the roundabout, take the 1st exit onto Redcliffe Hill The Grove Somerset St Fowlers of Bristol Commercial Rd Turn right onto Prince St River Avon A370 Turn right onto Middle Ave River Avon Clarence Rd Turn left onto Queen Square Destination will be on the left Source: KPMG LLP (UK) SAT NAV post code is BS1 4JP Rail The nearest station is Bristol Temple Meads, which is a ten minute walk from the office. Parking Parking is only available for Clients www.kpmg.co.uk kpmg.com/uk © 2017 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG Intaernational Cooperative, a Swiss entity. -

8 June 2010 No 17

8 June 2010 No 17 Hi, Help make Grove Wood a Local Nature Reserve On Thursday June 10th from 4pm, Bristol City Council's Cabinet will be discussing whether Grove Wood should be declared a Local Nature Reserve and whether they should consider compulsory purchasing the woods to secure its future for wildlife and public enjoyment. A Local Nature Reserve designation would ensure that Grove Wood was managed for wildlife, public enjoyment and educational use - just what the Snuff Mills Action Group have been calling for since 2008. You can help make this happen by: 1) Emailing [email protected] no later than noon on Wednesday June 9th [sorry about the short notice] stating why you think the Council should declare an LNR and buy Grove Wood Title your email: Grove Wood - Cabinet Discussions or something similar 2) Asking to speak at the Cabinet Meeting on June 10th - you need to request this in the email you send the Council 3) Joining Snuff Mills Action Group outside the Council House on College Green on Thursday June 10th at 3.30pm to show how much you want this to happen - make and bring banners! Check the Snuff Mills Action Group blog for more information at http://snuffmills.blogspot.com The report to cabinet can be seen by following the links for the 10th June Cabinet meeting at www.bristol.gov.uk/meetings There was also an article in today's Evening Post, see http://tinyurl.com/24cvo6l ------------------------- Area Green Space Plan Consultation As I mentioned in my last update, the AGSP consultation is starting on Monday (14th June). -

Vision West of England Feb 2020

Information and Events Update February 2020 Welcome to Vision West of England’s monthly round up of what’s on in your area. Thank you everyone who has contributed information, we hope you will find it useful. Monthly Sight Loss Drop-In Clinics Community Sight Loss Advisors hold several drop-In clinics in accessible locations across Bristol, Bath and South Gloucestershire. The aim of the drop-In is to provide information, advice and guidance for living with Sight Loss. There will also be a display of demonstration equipment including technology and daily living aids for you to try out. You are free to drop in but if you’d like to discuss anything specific please do call us so we can book you a 1-1 appointment. New locations at Bradley Stoke, Thornbury and Keynsham Bradley Stoke Library 20th February 10am-1pm, runs the 3rd Thursday each month Bradley Stoke Active Centre, Fiddlers Wood Lane, BS32 9B Thornbury, Age UK South Gloucestershire 26th February 10am-1pm, will run the 4th Wednesday of the month Age UK, 56 Hight Street, Thornbury, BS35 2AW Keynsham Library 19th February 10am-1pm, runs the 3rd Wednesday each month Civic Centre, Market Street, Keynsham, BS31 1FS Bath Manvers Street Baptist Church 5th February 10am-1pm, runs the 1st Wednesday of the month Manvers Street, Bath, BA1 1JW Yate Library 11th February 2020, runs the 2nd Tuesday of the month, 10am - 1pm Unit 44 Yate Shopping Centre, West Walk, Yate BS37 4AX Bedminster Library 14th and 28th February 10am -1pm. This drop-in runs fortnightly on a Friday Bedminster Library, 4 Bedminster Parade, Bedminster, Bristol BS3 4AQ Coming soon! Midsomer Norton Town Hall Commencing in March 2020. -

Archdeaconry of Bristol) Which Is Part of the Diocese of Bristol

Bristol Archives Handlist of parish registers, non-conformist registers and bishop’s transcripts Website www.bristolmuseums.org.uk/bristol-archives Online catalogue archives.bristol.gov.uk Email enquiries [email protected] Updated 15 November 2016 1 Parish registers, non-conformist registers and bishop’s transcripts in Bristol Archives This handlist is a guide to the baptism, marriage and burial registers and bishop’s transcripts held at Bristol Archives. Please note that the list does not provide the contents of the records. Also, although it includes covering dates, the registers may not cover every year and there may be gaps in entries. In particular, there are large gaps in many of the bishop’s transcripts. Church of England records Parish registers We hold registers and records of parishes in the City and Deanery of Bristol (later the Archdeaconry of Bristol) which is part of the Diocese of Bristol. These cover: The city of Bristol Some parishes in southern Gloucestershire, north and east of Bristol A few parishes in north Somerset Some registers date from 1538, when parish registers were first introduced. Bishop’s transcripts We hold bishop’s transcripts for the areas listed above, as well as several Wiltshire parishes. We also hold microfiche copies of bishop’s transcripts for a few parishes in the Diocese of Bath and Wells. Bishop’s transcripts are a useful substitute when original registers have not survived. In particular, records of the following churches were destroyed or damaged in the Blitz during the Second World War: St Peter, St Mary le Port, St Paul Bedminster and Temple. -

Future of Redcliffe (SPD 3)

Future of Redcliffe FOREWORD The Future of Redcliffe Supplementary Planning Document has been guided by a groundbreaking initiative between Bristol City Council and the local community of Redcliffe working together on how the area shall be developed. Redcliffe Futures* brings together residents, businesses, developers and other agencies in a partnership where everyone can have a say about the changes happening in the area. The group started developing these ideas in 2001 and published the Redcliffe Neighbourhood Framework in November 2002. “Redcliffe Futures has been fully involved in developing this SPD. Both the Neighbourhood Framework and General Principles are the foundations of this Supplementary Planning Document and the Council thanks the group for all their hard work in helping to prepare this document. The Council and community now wish to work with landowners and developers to deliver the vision of this SPD.” Councillor Dennis Brown, Executive Member for Transport and Development Control, Bristol City Council * The group’s membership has included representatives from: Avon Fire Brigade, Arup, Business West, Bristol City Council, Bristol Civic Society, South West Primary Care Trust, Bristol Urban Villages Initiative, Buchanans' Wharf Management Company, Lyons Davidson Solicitors, Midshires Estates Ltd, Pattersons (Bristol) Ltd, Redcliffe Community Forum, Redcliffe Residents Association, Redcliffe Parade Environmental Association, St Mary Redcliffe Church, English Heritage, St Mary Redcliffe Church of England Primary School, United Bristol Healthcare Trust (UBHT), Custom House Management Company, Beckett Hall, Byzantium Restaurant. i Supplementary Planning Document Number 3 THE VISION FOR REDCLIFFE IS: A sustainable neighbourhood of compact, mixed-use development that is human-scale, accessible to all and respectful of the area’s history and character. -

Jan/Feb 2020

Keep Me I'm useful Bishopstonincluding Ashley Down, Horfield & St. Andrews Mattersissue 134, Jan/Feb 2020 New year, new goals? Let your Smile 0117 951 3026 Blossom Register & Book Online www.horfielddentalcare.co.uk Horfield Dental Care, 525 Gloucester Road, Bristol, BS7 8UG info@horfielddentalcare.co.uk Find Bishopston Matters on Facebook Follow @bishmatters on Twitter Dear Readers... Wishing you all a very Happy New Year! lot of fun when joining them too! Our local I hope 2020 brings you good health and community really does have a wealth of happiness! activities to help keep us happy. A new year is often a time of reflection Do join The Horfield Organic Community and a great time to make positive changes. Orchard for their annual Wassail on For me there is nothing more important Saturday 18 January, decorate the fruit than good health for my family and loved trees, sing and be merry to encourage a ones. We don't always take as good care great 2020 fruit harvest. of ourselves as we should. This issue we It's the most wanderful time of the year, bring you a Health & Wellbeing section when the fabulous creativity and community (pages 14–27) featuring some amazing spirit pops up on hundreds of local streets local therapists, opticians, yoga and pilates during the Window Wanderland weekend – instructors, life coaches, dentists and gyms Saturday 29 February to Monday 2 March. that can help ensure your good health and A family event not to be missed! keep it that way. I look forward to keeping you up to date Continuing this theme, on the centre pages on news and events taking place in our we focus on a number of local groups that community throughout 2020. -

Polling Station List Review 2014

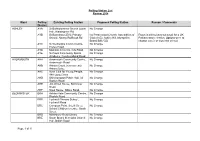

Polling Station List Review 2014 Ward Polling Existing Polling Station Proposed Polling Station Reason / Comments District ASHLEY AYA St Bartholomews Church Lower No Change Hall, Walsingham Rd AYB St Barnabas CEVC Primary Ivy Pentecostal Church, Assemblies of Room in school was too small for a UK School, Albany Rd/Brook Rd God (AoG), Ashley Hill, Montpelier, Parliamentary election. Options were to Bristol BS6 5JD change venue or close the school. AYC St Werburghs Comm Centre, No Change Horley Road AYD Malcolm X Centre, City Road No Change AYE St Pauls Community Sports No Change Academy, Newfoundland Road AVONMOUTH AHA Avonmouth Community Centre, No Change Avonmouth Road AHB Antona Court, (rear access) No Change Antona Drive. AHC Avon Club for Young People, No Change 98A Long Cross AHD Shirehampton Public Hall, 32 No Change Station Road AHE Jim O'Neil House, Kilminster No Change Road. AHF Stow House, Nibley Road. No Change BEDMINSTER BRA Ashton Vale Community Centre, No Change Risdale Road BRB Luckwell Primary School, No Change Luckwell Road BRC Compass Point, South Street No Change School Children’s centre, South Street BRD Marksbury Road Library No Change BRE South Bristol Methodist Church No Change Hall, British Road Page 1 of 11 Polling Station List Review 2014 Ward Polling Existing Polling Station Proposed Polling Station Reason / Comments District BISHOPSTON BSA Bishop Road Primary School No Change BSB St Michaels church Centre 160a No Change Gloucester Rd BSC Ashley Down Junior School, No Change Brunel Field BSD Ashley Down Junior -

Minutes of the BOPF Management Committee Meeting at the Council

Bristol Older People’s Forum CIO Canningford House, 38 Victoria Street, Bristol BS1 6BY Tel: 0117 927 9222, email: [email protected] Registered Charity Number: 1162616 BOPF & VIP Open Forum Meeting Thursday 28 November 2019, Broadmead Baptist Church, 1st flr, 10:30 – 12.30 Union Street (next to Tesco Express), Bristol, BS1 3HY MINUTES Present Trustees: Ian Bickerton, Chair (IB), Judith Brown, BOPF Ambassador (JB), Christina Stokes, Treasurer (CS), Trish Mensah (TM), Gloria Morris (GM), Lyn Porter (LP), Jenny Smith (JS), Tony Wilson (TW) Staff: Ian Quaife, Engagement & Development Manager, Lucy Rothwell, Project Support Worker. Minutes: Yolanda Pot, Finance and Admin Manager (YP) Members present: 53; non-members: 22; Total: 75 Event feedback forms: 27 Apologies David Elson (DE), Jo Stokes, LinkAge (co-opted Trustee) (JoS) 1. BOPF Chair, Ian Bickerton welcome, housekeeping and apologies Announcements and Updates The photographer, Morag took photos of the meeting, including head shots of the Trustees for the new BOPF website. On the tables were placed: Feedback form and Interview Q&A with Marvin Rees by IanQ. 2. Mayor of Bristol, Marvin Rees Clean Air & Transport and the One City Vision Marvin spoke about the main challenges that Bristol is facing today, with a focus on housing and transport. In particularly how to build balanced communities to incorporate people from Bristol. He also spoke about the One City Vision. Q&A Q1 There are parking problems at Ashton Gate Estate; more Park and Rides would help. A1 That is now happening with the combined regional authority WECA. We have identified 8 new Park & Ride sites.