Regulation of Electronic Communications Networks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effects of the Limit Order Book on Price Dynamics

Effects of the Limit Order Book on Price Dynamics Tolga Cenesizoglu Georges Dionne Xiaozhou Zhou November 2014 CIRRELT-2014-60 Effects of the Limit Order Book on Price Dynamics Tolga Cenesizoglu1, Georges Dionne1,2,*, Xiaozhou Zhou1,2 1 Department of Finance, HEC Montréal, 3000 Côte-Sainte-Catherine, Montréal, Canada H3T 2A7 2 Interuniversity Research Centre on Enterprise Networks, Logistics and Transportation (CIRRELT) Abstract. In this paper, we analyze whether the state of the limit order book affects future price movements in line with what recent theoretical models predict. We do this in a linear vector autoregressive system which includes midquote return, trade direction and variables that are theoretically motivated and capture different dimensions of the information embedded in the limit order book. We find that different measures of depth and slope of bid and ask sides as well as their ratios cause returns to change in the next transaction period in line with the predictions of Goettler, Parlour, and Rajan (2009) and Kalay and Wohl (2009). Limit order book variables also have significant long term cumulative effects on midquote return, which is stronger and takes longer to be fully realized for variables based on higher levels of the book. In a simple high frequency trading exercise, we show that it is possible in some cases to obtain economic gains from the statistical relation between limit order book variables and midquote return. Keywords. High frequency limit order book, high frequency trading, high frequency transaction price, asset price, midquote return, high frequency return. Results and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of CIRRELT. -

Portfolio Management Under Transaction Costs

Portfolio management under transaction costs: Model development and Swedish evidence Umeå School of Business Umeå University SE-901 87 Umeå Sweden Studies in Business Administration, Series B, No. 56. ISSN 0346-8291 ISBN 91-7305-986-2 Print & Media, Umeå University © 2005 Rickard Olsson All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior consent of the author. Portfolio management under transaction costs: Model development and Swedish evidence Rickard Olsson Master of Science Umeå Studies in Business Administration No. 56 Umeå School of Business Umeå University Abstract Portfolio performance evaluations indicate that managed stock portfolios on average underperform relevant benchmarks. Transaction costs arise inevitably when stocks are bought and sold, but the majority of the research on portfolio management does not consider such costs, let alone transaction costs including price impact costs. The conjecture of the thesis is that transaction cost control improves portfolio performance. The research questions addressed are: Do transaction costs matter in portfolio management? and Could transaction cost control improve portfolio performance? The questions are studied within the context of mean-variance (MV) and index fund management. The treatment of transaction costs includes price impact costs and is throughout based on the premises that the trading is uninformed, immediate, and conducted in an open electronic limit order book system. These premises characterize a considerable amount of all trading in stocks. -

INET to Join NASDAQ's Supermontage New York, NY— Instinet ECN And

INET to join NASDAQ's SuperMontage New York, NY— Instinet ECN and Island ECN, soon to be combined into one electronic marketplace branded INET, today announced plans to participate in NASDAQ's SuperMontage. INET will begin displaying orders on SuperMontage in January following the consolidation of the Island ECN and Instinet ECN. "We are committed to exposing our customers' orders to as much liquidity as possible and improving the marketplace for all investors," said Alex Goor, executive vice president, head of Alternative Trading Systems, Instinet Corporation. "As a result of NASDAQ's recent proposed rule changes, we expect that participation in SuperMontage will benefit our subscribers." "With Instinet's participation, SuperMontage offers a deeper pool of liquidity for NASDAQ market participants and ultimately, enhanced opportunity for best execution," said Chris Concannon, executive vice president of The NASDAQ Stock Market. "SuperMontage was designed to provide a highly transparent, highly liquid venue where multiple parties -- and competing market models -- can come together to yield the best outcome for investors." Separately, NASDAQ announced that it intends to use Instinet SmartRouter technology to provide its members with access to enhanced routing services. Instinet SmartRouter integrates liquidity pools including all major ECNs through its order routing algorithm. "NASDAQ is pleased to announce that it intends to partner with INET to make available Instinet's enhanced order-routing technology to NASDAQ's SuperMontage participants," Concannon added. Instinet ECN and Island ECN, soon to be combined into one electronic marketplace branded INET, will comprise one of the largest liquidity pools in U.S. over-the-counter securities. -

Filing for SEC Rule

Rule 606 Quarterly Report Instinet, LLC 309 West 49th Street New York, NY 10019 Disclosure of Order Routing Information – SEC Rule 606 for Quarter Ending on June 28 2019 In accordance with Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) requirements, Instinet, LLC (“Instinet” or the “Firm”), is publishing statistical information about its routing of certain customers’ orders in NMS Securities and Listed Options. SEC rules require all registered broker- dealers that route orders in certain equity and option securities to make publicly available quarterly reports that present a general overview of a firm’s non-directed order routing practices. Non-directed orders are orders that the customer has not instructed to route to a particular venue for execution. For these non-directed orders, the Firm has selected the execution venue on behalf of its customers. Please note that consistent with the SEC’s requirements, these statistics capture only a portion of Instinet's order flow. This report is intended to provide an overview of Instinet’s order routing practices, and does not create a reliable basis on which to assess whether Instinet or any other trading venue, to which we route orders, has satisfied its duty of best execution. Decisions concerning whether to open an account or direct orders to the Firm should not be established on the information presented in this report alone, but on a broader evaluation of the full range of services and products Instinet provides. This report is divided into four sections: 1. Securities listed on the New York Stock Exchange, LLC and reported as Network A eligible securities; 2. -

The Order Book As a Queueing System: Average Depth and Influence of the Size of Limit Orders Ioane Muni Toke

The order book as a queueing system: average depth and influence of the size of limit orders Ioane Muni Toke To cite this version: Ioane Muni Toke. The order book as a queueing system: average depth and influence of the size of limit orders. Quantitative Finance, Taylor & Francis (Routledge), 2015, 15 (5), pp.795-808. 10.1080/14697688.2014.963654. hal-01006410 HAL Id: hal-01006410 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01006410 Submitted on 16 Jun 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The order book as a queueing system: average depth and influence of the size of limit orders Ioane Muni Toke ERIM, University of New Caledonia BP R4 98851 Noumea CEDEX, New Caledonia [email protected] Applied Maths Laboratory, Chair of Quantitative Finance Ecole Centrale Paris Grande Voie des Vignes, 92290 Chˆatenay-Malabry, France [email protected] Abstract In this paper, we study the analytical properties of a one-side order book model in which the flows of limit and market orders are Poisson processes and the distribution of lifetimes of cancelled orders is exponen- tial. -

Informed Traders and Limit Order Markets$

ARTICLE IN PRESS Journal of Financial Economics 93 (2009) 67–87 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Financial Economics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jfec Informed traders and limit order markets$ Ronald L. Goettler a,Ã, Christine A. Parlour b, Uday Rajan c a Booth School of Business, University of Chicago, USA b Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley, USA c Ross School of Business, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA article info abstract Article history: We consider a dynamic limit order market in which traders optimally choose whether to Received 1 January 2008 acquire information about the asset and the type of order to submit. We numerically Received in revised form solve for the equilibrium and demonstrate that the market is a ‘‘volatility multiplier’’: 17 June 2008 prices are more volatile than the fundamental value of the asset. This effect increases Accepted 6 August 2008 when the fundamental value has high volatility and with asymmetric information Available online 5 April 2009 across traders. Changes in the microstructure noise are negatively correlated with JEL classification: changes in the estimated fundamental value, implying that asset betas estimated from G14 high-frequency data will be incorrect. C63 & 2009 Published by Elsevier B.V. C73 D82 Keywords: Limit order market Informed traders Endogenous information acquisition Computational game 1. Introduction Understanding dynamic order choice under asym- metric information is important because rational agents Many financial markets around the world, including use different trading strategies for different assets. The the Paris, Stockholm, Shanghai, Tokyo, and Toronto stock characteristics of an asset (such as the volatility of exchanges, are organized as limit order books. -

Single Stock Dividend Futures

EURONEXT DERIVATIVES SINGLE STOCK DIVIDEND FUTURES What are Single Stock Why trade Single Stock Who are Single Stock Dividend Futures? Dividend futures? Dividend Futures for? Single Stock Dividend Futures are Access new trading opportunities Investors who want to hedge risk exchange-traded derivatives contracts by taking long or short positions associated with dividend exposure, that allow investors to take positions on Single Stock Dividend Futures, diversify their trading portfolio and on dividend payments. or trade them against the dividend reduce its volatility exposure. index futures (CAC 40® or AEX Index®). Market Makers Euronext’s new Single Stock Dividend Futures complement its existing dividend index future offering (CAC 40 Dividend BNP Paribas Index Future and AEX Dividend Index Future), giving market Yanis Escudero participants additional investment strategies. [email protected] +44 (0) 207 595 1691 Dividends are a key component for equity and equity derivatives holders and are mostly used as a hedging tool. However, dividends are also becoming an asset Gabriel Messika class of their own: a dividend investment can be seen as corresponding to an [email protected] equity investment, while often proving more resilient and less volatile than stocks. +44 (0) 207 595 1819 Why trade Single Stock Dividend Futures? Nicolas Certner Benefit from an efficient hedging tool helping you to manage your [email protected] dividend exposure +44 (0) 207 595 595 1342 Diversify your portfolio by investing -

Dark Pools and High Frequency Trading for Dummies

Dark Pools & High Frequency Trading by Jay Vaananen Dark Pools & High Frequency Trading For Dummies® Published by: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, www.wiley.com This edition first published 2015 © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, West Sussex. Registered office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or trans- mitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor men- tioned in this book. -

Electronic Call Market Trading Nicholas Economides and Robert A

VOLUME 21 NUMBER 3 SPRING 1995 Electronic Call Market Trading Nicholas Economides and Robert A. Schwartz Hidden Limit Orders on the NYSE Thomas H.Mclnish and Robert A. Wood Benchmark Orthogonality Properties David E. Tierney and Jgery K Bailey - Equity Style ClassXcations Jon A. Christophmon "'Equity Style Classi6ications": Comment Charles A. Trzn'nka Corporate Governance: There's Danger in New Orthodoxies Bevis Longstreth Industry and Country EfZ'ects in International Stock Returns StmL. Heston and K. Ceert Routuenhont Currency Risk in International Portfolios: How Satisfying is Optimal Hedging? Grant W Gardner and Thieny Wuilloud Fundamental Analysis, Stock Prices, and the Demise of Miniscribe Corporation Philip D. Drake and John W Peavy, LLI Market Timing Can Work in the Real World Glen A. Lmm,Jt., and Gregory D. Wozniak "Market Timing Can Work in the Real World": Comment Joe Brocato and ER. Chandy Testing PSR Filters with the Stochastic Dominance Approach Tung Liang Liao and Peter Shyan-Rong Chou Diverfication Benefits for Investors in Real Estate Susan Hudson- Wonand Bernard L. Elbaum A PUBLICATION OF INSTITUTIONAL INVESTOR, INC. Electronic Call Market Trading Let competition increase @n'ency. Nicholas Economides and Robert A. Schwartz ince Toronto became the first stock exchange to computerize its execution system in 1977, electronic trading has been instituted in Tokyo S(1 982), Paris (1986), Australia (1990), Germany (1991). Israel (1991), Mexico (1993). Switzerland (1995), and elsewhere around the globe. Quite likely, by the year 2000, floor trading will be totally eliminat- ed in Europe, predominantly in favor of electronic con- tinuous markets. Some of the new electronic systems are call mar- kets, however, including the Tel Aviv StockExchange, the Paris Bourse (for thinner issues), and the Bolsa Mexicana's intermediate market. -

New Approach to the Regulation of Trading Across Securities Markets, A

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VoLuME 71 DECEMBER 1996 - NUM-BER 6 A NEW APPROACH TO THE REGULATION OF TRADING ACROSS SECURITIES MARKETS YAKOV AMImHU* HAIM IVIENDELSON** In this Article, ProfessorsAmihud and Mendelson propose that a securities issuer should have the exclusive right to determine in which markets its securities will be traded, in contrast to the current regulatoryscheme under which markets may uni- laterally enable trading in securities without issuer consent Professors Amihud and Mendelson demonstrate that the tradingregime of a security affects its liquidity, and consequently its value, and that multinmarket tradingby some securitiesholders may produce negative externalities that harm securities holders collectively. Under the current scheme; some markets compete for orderflow from individuals by low- eringstandards, thereby creatingthe need for regulatoryoversight. A rule requiring issuer consent would protect the liquidity interests of issuers and of securitieshold- ers as a group. ProfessorsAmihud and Mendelson addresstie treatment of deriva- tive securities under their scheme, proposing a fair use test that would balance the issuer's liquidity interest against the public's right to use price information freely. The authors suggest that under their proposed rule, markets will compete to attract securities issuers by implementing and enforcing value-maximizing trading rules, thereby providing a market-based solution to market regulation. * Professor and Yamaichi Faculty Fellow, Stern School of Business, New York Univer- sity. B.S.S., 1969, Hebrew University, M.B.A., 1973, New York University, Ph.D., 1975. New York University. ** The James Irvin Miller Professor, Stanford Business School, Stanford University. B.Sc., 1972, Hebrew University, M.Sc., 1977, Tel Aviv University; Ph.D., 1979, Tel Aviv University. -

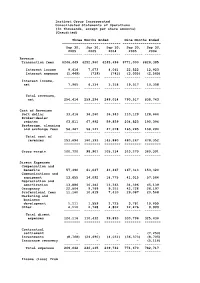

Instinet Group Incorporated Consolidated Statements of Operations (In Thousands, Except Per Share Amounts) (Unaudited)

Instinet Group Incorporated Consolidated Statements of Operations (In thousands, except per share amounts) (Unaudited) Three Months Ended Nine Months Ended ----------------------------- ------------------- Sep 30, Jun 30, Sep 30, Sep 30, Sep 30, 2005 2005 2004 2005 2004 --------- --------- -------- --------- -------- Revenue Transaction fees $246,449 $252,960 $245,696 $771,000 $828,385 Interest income 9,414 7,073 4,061 22,522 12,923 Interest expense (1,449) (739) (743) (3,005) (2,565) -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- Interest income, net 7,965 6,334 3,318 19,517 10,358 -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- Total revenues, net 254,414 259,294 249,014 790,517 838,743 -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- Cost of Revenues Soft dollar 33,416 36,260 36,943 110,129 128,664 Broker-dealer rebates 63,811 67,992 59,859 204,823 190,394 Brokerage, clearing and exchange fees 56,467 56,141 47,078 165,295 159,294 -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- Total cost of revenues 153,694 160,393 143,880 480,247 478,352 -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- Gross margin 100,720 98,901 105,134 310,270 360,391 -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- Direct Expenses Compensation and benefits 57,390 61,047 43,467 167,313 153,320 Communications and equipment 13,655 14,092 18,775 41,015 57,564 Depreciation and amortization 13,886 10,382 13,363 34,396 45,139 Occupancy 22,804 9,769 9,351 42,728 28,197 Professional fees 11,160 10,815 7,410 29,087 20,568 Marketing and business development 1,111 1,559 2,725 3,781 10,655 Other -

Instinet Group Incorporated Second Quarter 2005 Earnings ______Conference Call Transcript July 22, 2005

Instinet Group Incorporated Second Quarter 2005 Earnings _____________________________________________________ Conference Call Transcript July 22, 2005 CORPORATE PARTICIPANTS Lisa Kampf Instinet Group - Investor Relations Ed Nicoll Instinet Group - CEO John F. Fay Instinet Group – Co-President and CFO CONFERENCE CALL PARTICIPANTS Alex Kremm Lehman Brothers - Analyst Daniel Goldberg Bear Stearns – Analyst Charlotte Chamberlain Jeffries & Company – Analyst ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Instinet Group Incorporated. 2Q05 Earnings Call 1 Operator: Good morning ladies and gentlemen. This is the operator. Today’s conference is scheduled to begin momentarily. Until that time, your lines will again be placed on music hold. Thank you for your patience. Good morning. My name is Cynthia and I will be your conference facilitator. At this time I would like to welcome everyone to the Instinet Group, Incorporated Second Quarter 2005 Earnings conference call. All lines have been placed on mute to prevent any background noise. After the speaker’s remarks there will be a question and answer period. If you would like to ask a question during this time, simply press star then the number 1 on your telephone keypad. If you would like to withdraw your question, press star then the number 2. I would now like to turn the conference over to Lisa Kampf, Investor Relations Officer. Ma’am, you may begin your conference. Lisa Kampf: Good morning and welcome to the Instinet Group conference call to discuss results for the second quarter of 2005. During this conference call we may make statements that are forward looking in nature. Our actual results may be materially different from the results anticipated in those statements.