JOMEC Journal Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (Guess)

THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) A Dissertation by Mikki Hoang Phan Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2012 Bachelor of Arts, Wichita State University, 2008 Submitted to the Department of Psychology and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Mikki Phan All Rights Reserved THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a major in Psychology. _____________________________________ Barbara S. Chaparro, Committee Chair _____________________________________ Joseph Keebler, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jibo He, Committee Member _____________________________________ Darwin Dorr, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member Accepted for the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences _____________________________________ Ronald Matson, Dean Accepted for the Graduate School _____________________________________ Abu S. Masud, Interim Dean iii DEDICATION To my parents for their love and support, and all that they have sacrificed so that my siblings and I can have a better future iv Video games open worlds. — Jon-Paul Dyson v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Althea Gibson once said, “No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you.” Thus, completing this long and winding Ph.D. journey would not have been possible without a village of support and help. While words could not adequately sum up how thankful I am, I would like to start off by thanking my dissertation chair and advisor, Dr. -

Force Awakens’ Edition

TUESDAY, AUGUST 18, 2015 TECHNOLOGY AT&T helped US NSA in spying on Internet traffic WASHINGTON: Telecommunications customer. network hubs in the United States. and I.S.P.s,” or Internet service providers, access to contents of transiting email powerhouse AT&T Inc has provided The documents date from 2003 to AT&T installed surveillance equip- according to another NSA document. traffic years before Verizon started in extensive assistance to the US National 2013 and were provided by fugitive for- ment in at least 17 of its US Internet AT&T started in 2011 to provide the March 2013, the Times reported. Security Agency as the spy agency con- mer NSA contractor Edward Snowden, hubs, far more than competitor Verizon NSA more than 1.1 billion domestic cell- Asked to comment on the Times ducts surveillance on huge volumes of the Times reported. The company Communications Inc, the Times report- phone calling records daily after “a push report, AT&T spokesman Brad Burns told Internet traffic passing through the helped the spy agency in a broad range ed. AT&T engineers also were the first to to get this flow operational prior to the Reuters by email: “We do not voluntarily United States, the New York Times of classified activities, the newspaper use new surveillance technologies 10th anniversary of 9/11,” referring to provide information to any investigat- reported on Saturday, citing newly dis- reported. invented by the NSA, the Times report- the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks on the United ing authorities other than if a person’s closed NSA documents. -

Inside the Video Game Industry

Inside the Video Game Industry GameDevelopersTalkAbout theBusinessofPlay Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman Downloaded by [Pennsylvania State University] at 11:09 14 September 2017 First published by Routledge Th ird Avenue, New York, NY and by Routledge Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business © Taylor & Francis Th e right of Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman to be identifi ed as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections and of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act . All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice : Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identifi cation and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Names: Ruggill, Judd Ethan, editor. | McAllister, Ken S., – editor. | Nichols, Randall K., editor. | Kaufman, Ryan, editor. Title: Inside the video game industry : game developers talk about the business of play / edited by Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman. Description: New York : Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa Business, [] | Includes index. Identifi ers: LCCN | ISBN (hardback) | ISBN (pbk.) | ISBN (ebk) Subjects: LCSH: Video games industry. -

American Broadcasting Company from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search for the Australian TV Network, See Australian Broadcasting Corporation

Scholarship applications are invited for Wiki Conference India being held from 18- <="" 20 November, 2011 in Mumbai. Apply here. Last date for application is August 15, > 2011. American Broadcasting Company From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search For the Australian TV network, see Australian Broadcasting Corporation. For the Philippine TV network, see Associated Broadcasting Company. For the former British ITV contractor, see Associated British Corporation. American Broadcasting Company (ABC) Radio Network Type Television Network "America's Branding Broadcasting Company" Country United States Availability National Slogan Start Here Owner Independent (divested from NBC, 1943–1953) United Paramount Theatres (1953– 1965) Independent (1965–1985) Capital Cities Communications (1985–1996) The Walt Disney Company (1997– present) Edward Noble Robert Iger Anne Sweeney Key people David Westin Paul Lee George Bodenheimer October 12, 1943 (Radio) Launch date April 19, 1948 (Television) Former NBC Blue names Network Picture 480i (16:9 SDTV) format 720p (HDTV) Official abc.go.com Website The American Broadcasting Company (ABC) is an American commercial broadcasting television network. Created in 1943 from the former NBC Blue radio network, ABC is owned by The Walt Disney Company and is part of Disney-ABC Television Group. Its first broadcast on television was in 1948. As one of the Big Three television networks, its programming has contributed to American popular culture. Corporate headquarters is in the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City,[1] while programming offices are in Burbank, California adjacent to the Walt Disney Studios and the corporate headquarters of The Walt Disney Company. The formal name of the operation is American Broadcasting Companies, Inc., and that name appears on copyright notices for its in-house network productions and on all official documents of the company, including paychecks and contracts. -

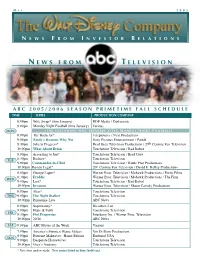

N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N

M A Y 2 0 0 5 N E W S F R O M I N V E S T O R R E L A T I O N S N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N A B C 2 0 0 5 / 2 0 0 6 S E A S O N P R I M E T I M E F A L L S C H E D U L E TIME SERIES PRODUCTION COMPANY 8:00pm Wife Swap* (thru January) RDF Media / Diplomatic 9:00pm Monday Night Football (thru January) Various MON ( T H E F O L L O W I N G W I L L P R E M I E R E A F T E R M O N D A Y N I G H T F O O T B A L L ) 8:00pm The Bachelor* Telepictures / Next Productions 9:00pm Emily’s Reasons Why Not Sony Pictures Entertainment / Pariah 9:30pm Jake in Progress* Brad Grey Television Productions / 20th Century Fox Television 10:00pm What About Brian Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 8:00pm According to Jim* Touchstone Television / Brad Grey 8:30pm Rodney* Touchstone Television TUE 9:00pm Commander-in-Chief Touchstone Television / Battle Plan Productions 10:00pm Boston Legal* 20th Century Fox Television / David E. Kelley Productions 8:00pm George Lopez* Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / Fortis Films 8:30pm Freddie Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / The Firm WED 9:00pm Lost* Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 10:00pm Invasion Warner Bros. -

Fiscal Year 2015 Annual Financial Report and Shareholder Letter 10DEC201511292957

6JAN201605190975 Fiscal Year 2015 Annual Financial Report And Shareholder Letter 10DEC201511292957 10DEC201400361461 Dear Shareholders, The Force was definitely with us this year! Fiscal 2015 was another triumph across the board in terms of creativity and innovation as well as financial performance. For the fifth year in a row, The Walt Disney Company delivered record results with revenue, net income and earnings per share all reaching historic highs once again. It’s an impressive winning streak that speaks to our continued leadership in the entertainment industry, the incredible demand for our brands and franchises, and the special place our storytelling has in the hearts and lives of millions of people around the world. All of which is even more remarkable when you remember that Disney first started entertaining audiences almost a century ago. The world certainly looks a lot different than it did when Walt Disney first opened shop in 1923, and so does the company that bears his name. Our company continues to evolve with each generation, mixing beloved characters and storytelling traditions with grand new experiences that are relevant to our growing global audience. Even though we’ve been telling our timeless stories for generations, Disney maintains the bold, ambitious heart of a company just getting started in a world full of promise. And it’s getting stronger through strategic acquisitions like Pixar, Marvel and Lucasfilm that continue to bring new creative energy across the company as well as the constructive disruptions of this dynamic digital age that unlock new opportunities for growth. Our willingness to challenge the status quo and embrace change is one of our greatest strengths, especially in a media market rapidly transforming with each new technology or consumer trend. -

GAME, Games Autonomy Motivation & Education

G.A.M.E., Games autonomy motivation & education : how autonomy-supportive game design may improve motivation to learn Citation for published version (APA): Deen, M. (2015). G.A.M.E., Games autonomy motivation & education : how autonomy-supportive game design may improve motivation to learn. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2015 Document Version: Publisher’s PDF, also known as Version of Record (includes final page, issue and volume numbers) Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

Device Management with Wavelink Avalanche Enabler User's Guide

Device Management with Wavelink Avalanche® Enabler User’s Guide Disclaimer Honeywell International Inc. (“HII”) reserves the right to make changes in specifications and other information contained in this document without prior notice, and the reader should in all cases consult HII to determine whether any such changes have been made. The information in this publication does not represent a commitment on the part of HII. HII shall not be liable for technical or editorial errors or omissions contained herein; nor for incidental or consequential damages resulting from the furnishing, performance, or use of this material. HII disclaims all responsibility for the selection and use of software and/or hardware to achieve intended results. This document contains proprietary information that is protected by copyright. All rights are reserved. No part of this document may be photocopied, reproduced, or translated into another language without the prior written consent of HII. © 2004-2014 Honeywell International Inc. All rights reserved. Web Address: www.honeywellaidc.com Trademarks RFTerm is a trademark or registered trademark of EMS Technologies, Inc. in the United States and/or other countries. Microsoft® Windows®, ActiveSync®, Windows XP®, MSN, Outlook®, Windows Mobile®, the Windows logo, and Windows Media are registered trademarks or trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the United States and/or other countries. Summit Data Communications, Inc. Summit Data Communications, the Summit logo, and “The Pinnacle of Performance” are trademarks of Summit Data Communications, Inc. The Bluetooth® word mark and logos are owned by the Bluetooth SIG, Inc. Wavelink®, Wavelink Avalanche®, the Wavelink logo and tagline, Wavelink Studio™, Avalanche Management Console™, Mobile Manager™, and Mobile Manager Enterprise™ are trademarks of Wavelink Corporation, Kirkland. -

Marvel Trading Card Game Pc Guide

marvel trading card game pc guide Download marvel trading card game pc guide A collectible card game (CCG), also called a trading card game (TCG) or customizable card game, is a kind of card game that first emerged in 1993 and consists of. Marvel Heroes is a free to play 3D action RPG. Here you will find some Marvel Heroes reviews, download, guides, videos, screenshots, news, tips and more. Le jeu de cartes LCG (Living Card Game) en VO ou JCE (Jeu de Carte Evolutif) en VF suit sa route tranquillement avec la sortie régulière de packs et d extensions. Overview New challengers Strider and Ghost Rider do battle in the updated Bonne Wonderland. Ultimate Marvel vs. Capcom 3, the standalone update to Marvel vs. Capcom 3. The best place to get cheats, codes, cheat codes, walkthrough, guide, FAQ, unlockables, tricks, and secrets for Marvel Nemesis: Rise Of The Imperfects for PlayStation. Star Wars The Card Game est un jeu de carte de type LCG (Living Card Game). L éditeur Fantasy Flight Games a choisi de ne pas mettre une notion de rareté, au. Marvel s mightiest heroes come to life as you play without limits in Disney Infinity 2.0: Marvel Super Heroes on PlayStation 4, Xbox One, Wii U, PlayStation 3 and. Get the latest Pokemon Trading Card Game cheats, codes, unlockables, hints, Easter eggs, glitches, tips, tricks, hacks, downloads, hints, guides, FAQs, walkthroughs. Alphabetical list of games.hack//Enemy Trading Card Game (Decipher, Inc.) 007 Spy Cards (GE Fabbri) (January 2008) 24 Trading Card Game (Press Pass, Inc.) (August 2007) Cheatbook your source for Cheats, Video game Cheat Codes and Game Hints, Walkthroughs, FAQ, Games Trainer, Games Guides, Secrets, cheatsbook. -

Riot Games Ceo Brandon Beck Announced As Keynote Speaker for the 2015 D.I.C.E

RIOT GAMES CEO BRANDON BECK ANNOUNCED AS KEYNOTE SPEAKER FOR THE 2015 D.I.C.E. SUMMIT Additional Fourteen Speakers Round Out Full Speaker List LOS ANGELES – January 22, 2015 - The Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences confirmed Riot Games CEO Brandon Beck as the 2015 D.I.C.E. Summit opening keynote speaker taking place Feb. 3-5, 2015 at the Hard Rock Hotel Las Vegas. Fourteen additional speakers from among gaming industry technologists, gaming industry pioneers, and D.I.C.E. Awards nominated games will also be taking the stage. Invited speakers will draw from their unique experiences to share their perspective on the conference theme, Without Borders, to examine the ways in which we see barriers being transcended, and how creative industries can continue to drive entertainment forward. The prestigious group of speakers represents industry leaders from every region and across all areas of game development. All sessions will be live streamed via Twitch on www.twitch.tv/dice on Wednesday, Feb. 4th PST from 9:30 am to 5 pm and will resume Thursday, Feb. 5th PST from 9:30 AM to 4 PM. Following the Summit sessions will be the live stream of the 18th D.I.C.E. Awards on Thursday, Feb. 5th PST beginning at 7 PM. Newly confirmed to take the stage: • Brandon Beck, CEO and co-founder, created Riot Games in 2006 with a vision to build a game company that prioritizes the player experience in the way games are developed, delivered, and supported. Beck will open up the summit the morning of Wednesday, Feb. -

01 2014 FIFA World Cup Brazil 02 50 Cent : Blood on the Sand 03 AC/DC

01 2014 FIFA World Cup Brazil 02 50 Cent : Blood on the Sand 03 AC/DC Live : Rock Band Track Pack 04 Ace Combat : Assault Horizon 05 Ace Combat 6: Fires of Liberation 06 Adventure Time : Explore the Dungeon Because I DON'T KNOW! 07 Adventure Time : The Secret of the Nameless Kingdom 08 AFL Live 2 09 Afro Samurai 10 Air Conflicts : Vietnam 11 Air Conflicts Pacific Carriers 12 Akai Katana 13 Alan Wake 14 Alan Wake - Bonus Disk 15 Alan Wake's American Nightmare 16 Alice: Madness Returns 17 Alien : Isolation 18 Alien Breed Trilogy 19 Aliens : Colonial Marines 20 Alone In The Dark 21 Alpha Protocol 22 Amped 3 23 Anarchy Reigns 24 Angry Bird Star Wars 25 Angry Bird Trilogy 26 Arcania : The Complete Tale 27 Armored Core Verdict Day 28 Army Of Two - The 40th Day 29 Army of Two - The Devils Cartel 30 Assassin’s Creed 2 31 Assassin's Creed 32 Assassin's Creed - Rogue 33 Assassin's Creed Brotherhood 34 Assassin's Creed III 35 Assassin's Creed IV Black Flag 36 Assassin's Creed La Hermandad 37 Asterix at the Olympic Games 38 Asuras Wrath 39 Autobahn Polizei 40 Backbreaker 41 Backyard Sports Rookie Rush 42 Baja – Edge of Control 43 Bakugan Battle Brawlers 44 Band Hero 45 BandFuse: Rock Legends 46 Banjo Kazooie Nuts and Bolts 47 Bass Pro Shop The Strike 48 Batman Arkham Asylum Goty Edition 49 Batman Arkham City Game Of The Year Edition 50 Batman Arkham Origins Blackgate Deluxe Edition 51 Battle Academy 52 Battle Fantasía 53 Battle vs Cheese 54 Battlefield 2 - Modern Combat 55 Battlefield 3 56 Battlefield 4 57 Battlefield Bad Company 58 Battlefield Bad -

01 2014 FIFA World Cup Brazil 02 50 Cent : Blood on the Sand 03

01 2014 FIFA World Cup Brazil 02 50 Cent : Blood on the Sand 03 Adventure Time : Explore the Dungeon Because I DON'T KNOW! 04 Adventure Time : The Secret of the Nameless Kingdom 05 AFL Live 2 06 Afro Samurai 07 Air Conflicts : Vietnam 08 Alan Wake 09 Alan Wake's American Nightmare 10 Alien : Isolation 11 Aliens : Colonial Marines 12 Alone In The Dark 13 Anarchy Reigns 14 Angry Bird Star Wars 15 Angry Bird Trilogy 16 Arcania : The Complete Tale 17 Armored Core Verdict Day 18 Army Of Two - The 40th Day 19 Army of Two - The Devils Cartel 20 Assassin’s Creed 2 21 Assassin's Creed 22 Assassin's Creed - Rogue 23 Assassin's Creed III 24 Assassin's Creed IV Black Flag 25 Assassin's Creed La Hermandad 26 Asuras Wrath 27 Avatar – The Game 28 Baja – Edge of Control 29 Bakugan Battle Brawlers 30 Band Hero 31 Banjo Kazooie Nuts and Bolts 32 Batman Arkham Asylum Goty Edition 33 Batman Arkham City Game Of The Year Edition 34 Batman Arkham Origins Blackgate Deluxe Edition 35 Battle Academy 36 Battlefield 2 - Modern Combat 37 Battlefield 3 38 Battlefield 4 39 Battlefield Bad Company 40 Battlefield Bad Company 2 41 Battlefield Hardline 42 Battleship 43 Battlestations Pacific 44 Bayonetta 45 Ben 10 Omniverse 2 46 Binary Domain 47 Bioshock 48 Bioshock 2 49 Bioshock Infinity 50 BlackSite: Area 51 51 Blades of Time 52 Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War 53 Blink 54 Blood Knights 55 Blue Dragon 56 Blur 57 Bob Esponja La Venganza De Plankton 58 Borderlands 1 59 Borderlands 2 60 Borderlands The Pre Sequel 61 Bound By Flame 62 Brave 63 Brutal Legend 64 Bullet Soul