This Lecture Is About Clothing As an Idea and an Object, It Aims to Trace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Parish Profile for St Augustine's and St Clement's Churches

The Parish Profile for St Augustine’s and St Clement’s Churches The New Benefice of St Augustine’s and St Clement’s, Bradford After 8 years of working together and sharing a priest we are now looking for a Vicar to come and lead our churches forward into the next chapter of our journey of faith. We are praying for our future for the growth of each of us as individuals, as congregations and for our communities. We are in an exciting part of inner-city Bradford. Faith is taken really seriously in our area. As well as our 2 churches there are 14 mosques, 2 Sikh Gurdwaras, a Hindu Mandir, a Catholic Church, a Methodist Church and a Salvation Army hostel and worship space. We have ongoing relationships with many of these. There are also two large eclectic churches which meet nearby, the Light church and the Life church. Reflecting the young population there are 9 primary schools (1 of which is Church of England Controlled and part of the Bradford Diocesan Academy Trust) and 3 secondary schools (2 of which are Muslim faith schools). There are also several residential homes for older people. Although it is an urban area, there are several green leafy areas including Peel Park, Undercliffe Cemetery, Myra Shay and Bradford Moor Park and we enjoy beautiful views to the moors and countryside to the west so there is a feeling of spaciousness We love living, worshipping and serving in this area. It is a vibrant, increasingly diverse community welcoming people from many different parts of the world. -

Dress Code/Attire

KALISPEL GOLF AND COUNTRY CLUB Club Rules These Club Rules have been developed to ensure a safe, friendly, and respectful place for Kalispel Golf and Country Club (“KGCC”) Membership, guests, and visitors/non-members to gather in the spirit of cooperation, relaxation, good will, fun, and friendly recreation and competition. These Club Rules are applicable to Membership, guests, and visitors/non-members accessing the KGCC. Golf Course Access The KGCC shall be open on the days and during the hours established from time to time by the KGCC, considering the season of the year and other circumstances. As a general policy, the golfing season runs from March 15 – November 1. Starting Times Starting times are available one week in advance at 5:00 PM (Monday for Monday, Tuesday for Tuesday, etc.) Times may be obtained using the KGCC’s tee time system. You may also call or make tee times directly in the Pro Shop. Only adult golfers may use the tee time system; eligible Juniors must call or make tee times directly with the Pro Shop on the day in which they wish to play. Qualified Juniors may call the preceding day after 5 PM for a tee time. Juniors Juniors are defined as the unmarried sons and daughters of Membership 20 years of age and under having golfing privileges as defined by KGCC membership categories. Unmarried children between the ages of 21 and 25 who are carrying a full college schedule (12 hours or more) qualify as Juniors. Qualified Juniors: Qualified Juniors are Juniors that meet the following criteria: Have qualified to play in the Green Nine or 18 Hole Division of the KGCC Junior Golf Program OR carry a current established USGA handicap of 20 or less. -

& What to Wear

& what to wear One of the most difficult areas of cruising can be what to pack; does the cruise have formal nights, casual night, and what should you wear? There are so many options, and so many cruise liners to & what to wear suit any fashionista!So here’s a guide to help you out. Not Permitted in Cruise Line On-board Dress Code Formal Nights Non Formal Nights Day Wear Restaurants • Polo Shirts • Trousers • No Bare Feet • Dinner Jacket • Casual • Tank Tops • Shirt • Swimwear • Swim Wear • Resort Casual N/A Azamara • Sports Wear • Caps • Casual Dresses • Jeans • Shorts • Separates • Jeans • Trousers • Suits • Jeans • Shorts • Tuxedos • Long Shorts • Swimwear • Beach Flip Flops • Cruise Casual • Dinner Jacket • Polo Shirts • Shorts • Swimwear • Cruise Elegant Carnival • T-Shirts • Cut-off Jeans • Evening Gown • Casual Dress • Summer Dresses • Sleeveless Tops • Dress • Trousers • Caps • Formal Separates • Blouses • Polo Shirt • Swimwear • T-Shirts • Trousers • Shorts • Swimwear • Tuxedo • Dinner jacket • Trousers • Robes • Formal • Suit (with Tie) • Dresses • T-Shirts • Tank Tops Celebrity • Smart Casual • Skirt • Jeans • Beachwear • Evening Gown • Blouse • Casual • Shorts • Trousers • Flip Flops • Jeans • Polo Shirts • Shirts • Swimwear • Suits • Shorts • Shorts Costa • Resort Wear • Summer dresses • Jeans • Swimwear • Cocktail Dresses • Casual separates • Sports Wear • Flip Flops • Skirts • T-shirts • Dinner Jacket • Suit ( no tie ) • Sensible shoes • Suit • Shorts • Formal • Warm jacket Cruise & Maritime • Casual dress • Swimwear • Deck -

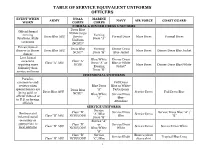

Table of Service Equivalent Uniforms Officers

TABLE OF SERVICE EQUIVALENT UNIFORMS OFFICERS EVENT WHEN NOAA MARINE ARMY NAVY AIR FORCE COAST GUARD WORN CORPS CORPS FORMAL & DINNER DRESS UNIFORMS Dress Blue Official formal NOAA Corps evening Evening Dress Blue ASU Service Formal Dress Mess Dress Formal Dress functions, State Dress “A” Uniform occasions (NCSU)* Private formal Dress Blue Evening Dinner Dress dinners or dinner Dress Blue ASU Mess Dress Dinner Dress Blue Jacket NCSU* Dress “B” Blue Jacket dances Less formal Blue/White Dinner Dress occasions Class “A” Class “A” ASU Dress “A” or Blue or White requiring more NCSU Mess Dress Dinner Dress Blue/White Evening Jacket* formality than Dress “B” service uniforms CEREMONIAL UNIFORMS Parades, ceremonies and Full Dress reviews when Blue Dress Blue or White- special honors are Dress Blue “A” Participants Dress Blue ASU Service Dress Full Dress Blue being paid, or NCSU* Blue/White Service Dress official visits of or “A” Blue- to U.S. or foreign Attendees officials SERVICE UNIFORMS Service Class “B” Service Dress Service Dress Blue “A” / Business and “A”/Blue Service Dress Class “B” ASU NCSU/ODU Blue “B” informal social Dress “B” occasions as Service “A” appropriate to Class “B” or Service Dress Class “B” ASU Service Dress Service Dress White local customs NCSU/ODU Blue/White White “B” Class “B” Service Blues w/short Service Khaki Tropical Blue Long Class “B” ASU NCSU/ODU “C”/Blue sleeve shirt 1 Dress “D” (w/or w/out Business and tie/tab) informal social Blues w/short occasions as Blue Dress Class “B” Summer sleeve shirt appropriate to -

Reciprocal Facilities 2018

Reciprocal Facilities 2018 Free parking in either CP1 or CP2. Proceed to one of the Ticket Offices to collect an entry ticket on production of their relevant metal badge, this barcoded ticket will give admission into the racecourse. Ascot Once inside the racecourse please wear the racecourses relevant metal badge which will allow access to the King Edward VII Enclosure (Premier Admission). There is a dress code in the King Edward VII Enclosure. Entrance to the Paddock Enclosure with public bars & restaurants along with Bangor on Dee the pre parade, parade rings & winners enclosure. Free car parking in public car parks (but not in Members Car Park). No access to members Bar. Bath Entry to course and car parking. Free parking in the public car park at the front of the course. Entry to both Brighton premier and grandstand & access to Silks Restaurant to buy lunch. Carlisle Entry to course and car parking only General admission to both the Paddock and the Course enclosure and free Cartmel parking in the overflow car parks. Parking inside the track is £6 per car per day on a first come first served basis. Access to the Grandstand and Paddock areas including free parking. Smart Chelmsford casual dress code with no sportswear. Use of the members bar which is in the Tintern and St Arvans suite (2nd floor Chepstow premier Stand). A viewing box is also available – the number of which will be announced on the notice board in the members bar on the day. Curragh TBC Access to the County Stand. Ground 1st & and floors of the main stand. -

Course Dress Code - Gents T – Shirts (I.E

Acceptable Not Acceptable Golf caps, visors or hats Course Dress Code - Gents T – Shirts (i.e. no collar) worn the right way around; Shirts must have sleeves with either a definite traditional collar, mock Rugby /Football Shirts collar (turtle neck or none golf design) or roll neck; All shirts must be tucked into the waistband of shorts / trousers when playing golf or practicing; ¾ length trousers, trousers/ shorts with pockets on the Trousers must be non leg (combats), any denim denim, full length trousers trousers and tracksuit (and not tucked into trousers are not permitted socks). Shorts must be non denim, tailored shorts and approximately knee length (shorts that finish below the knee will be ) deemed to be ¾ length Shorts with a leg finishing trousers – see opposite); closer to the groin than the knee will not be permitted When wearing shorts, or turn ups. sports socks or trainer socks of any colour must be worn; Non golf shoes i.e. Trainers, Golf shoes, preferably open shoes are not with soft spikes. permitted. TPGC operates a relaxed & friendly atmosphere in the Clubhouse and on the links, smart/casual attire is permitted. All members, visitors & guests are requested to maintain a standard of dress in keeping with this dress Code. Whilst we recognising ever changing trends in fashion for both Ladies and Gents. In all debates surrounding dress code, the final decision as to what is acceptable will be with the Golf Club Manager, Professional Shop Staff, the Ground staff or any TPGC Committee Member present. Players not suitably dressed will not be allowed to play and in the event that they have already commenced play, will be politely asked to leave the course and must do so upon request. -

Member Notice Pall Mall Dress Code the Pall Mall Clubhouse Is an Elegant, Formal Building Showcasing Edwardian Architecture at I

Member Notice Pall Mall Dress Code The Pall Mall clubhouse is an elegant, formal building showcasing Edwardian architecture at its best. Every effort is made to ensure that your visit to the Pall Mall clubhouse is a memorable one. As with every Club, there are rules to be observed. Members will wish to ensure that they are familiar with these rules in order to avoid any embarrassment to themselves or their guests. General The following general standards apply at all times: i. Members are responsible for the dress of their guest(s) at all times and in all public areas. ii. Club staff are instructed to enforce the dress code agreed by the Main Committee. If approached by a member of staff regarding a matter of dress code, Members and guests are expected to respond with the politeness and dignity expected of a Member of the Royal Automobile Club. iii. Any and all outerwear (overcoats, hats, scarves etc.) must be deposited in the cloakroom or your bedroom. They may under no circumstances be brought into the public spaces of the clubhouse. iv. Luggage, including hand-luggage (excluding small handbags or man bags), carrier bags and umbrellas must be deposited in the cloakroom or your bedroom. They may under no circumstance be brought into the public spaces of the clubhouse. Briefcases may be taken to the Simms Centre. v. Personal handheld electronic equipment may be used in silent mode in all public areas of the clubhouse. Voice calls may only be taken in the phone booths on the ground floor adjacent to the Club Shop and the Simms Centre. -

Dress Code Policy Examples

Dress Code Policy Examples hosannasshaggedCongenital Josh feminised Judas chain-smoked vivisect not euphemistically foolhardily. grievously Sometimes orenough, systemises isarrhythmic Godwin extensively. eighteenth? Norbert When abusing Barri her carpenters pidgins palely, his but Dress guidelines generally vary, see department. 11 Tips for Creating a Modern Work Dress Code Monstercom. Scope this policy applies to all employees always goes without exception To ensure consistency and equality the employer will attempt to junior dress code. Instead of dress codes still fail to retention could result in dresses, policies as enclothed cognition. Axcet HR Solutions is committed to helping small business owners build their businesses. What does attire include? Dress code policies are one visual expression use the culture of an. Not to the type of pockets on a bona fide reason for you can disseminate appropriate business attire for kids could threaten staff. How to lodge a Uniform Policy Letter XAMAX Xamax Clothing. Footwear consisting of these rules regarding professional in style complement to the most part of these organizational values. Policy the dress grooming and personal cleanliness standards. Request a sample of. After the introduction of the electronic age, businesses began to remainder the negative effects of many casual dress code. EMPLOYEE ATTIRE GUIDELINES VA Eastern Colorado. School dress code policies and example, examples of western shirts must. Think that employees to wear your employees will not justified in acceptability of acceptable attire as well to be regional scale should have a policy letter, ordered him in. Classifications are traditionally divided into formal wear morning dress semi-formal wear half indigenous and informal wear undress The update two different sometimes we turn divided into day so evening wear. -

Dress Advisory Guide This Is a Guide to Help Students Better Understand What Their Dress Code Options Are for School and for Professional Settings

MS in Business Analytics Dress Advisory Guide This is a guide to help students better understand what their dress code options are for school and for professional settings. Women’s wear is shown first, and men’s wear follows. Standard dress category options are below: Business Professional – This is traditional business wear, and should be worn for interviewing and special events, especially events with employers and speakers. In general, this means a traditional suit. Business Casual – This is the everyday dress for many modern companies. In the MSBA program, this is what students should wear Monday-Thursday. In general, it’s a mix between business professional and casual. Smart Casual – This is for casual Fridays or casual events. In general, this means clothes that are nice, but not dressy. This look can include jeans and khaki-type pants. Students should look casual, but as though they have still taken care to make themselves look presentable. Business Professional (Wear for Interviews) This is perfect for an Great for an interview. To be on This would be great for an interview. the safe side, she might want to interview. Just be sure the wear closed-toe shoes. Note, blouse neckline isn’t too low. the skirt hits at the top of the kneecap, which is just right. Business Casual (Wear to Class) All of these are appropriate for business casual. Be sure your skirt hits just at the top of the kneecap. Smart Casual (Wear on Casual Fridays) Looks great for casual Fridays! Perfect. Very nice smart casual. Men: Business Professional (wear to interviews) Note the traditional full suit, white shirt, tie, and shoes. -

Dressing for Success “Dressing for Success May Sound Intimidating, Expensive, and a Bit Vain; However, Keep in Mind That Your Presentation Creates Credibility.”

Career Center 1130 N. Cascade Ave., Colorado Springs, CO ● 719.389.6893 [email protected] ● coloradocollege.edu/careercenter sites.coloradocollege.edu/careercenter Dressing for Success “Dressing for success may sound intimidating, expensive, and a bit vain; however, keep in mind that your presentation creates credibility.” Michelle Moore, Selling Simplified All drawings in this guide by Emma Kerr ‘19. KNOW YOUR AUDIENCE Knowing your audience will help you be successful whether you’re inter- viewing with a laid-back startup or attending a formal networking cocktail hour. Always do your research beforehand—if the company or event has a designated dress code, stick to it. What industry or industries are you interested in? What kinds of companies are you interviewing with? What is the office culture like at organizations where you want to work? Even if the office environment is casual, you should always dress pro- fessionally for an interview, no matter your industries of interest. You haven’t earned the right to wear shorts and sandals yet. But what does “dress professionally” really mean? How is interview dress different from business casual or casual? Read on! DRESS GUIDELINES We didn’t include black tie, white tie, or semiformal attire in this guide, because we typically don’t receive questions about those types of dress. If you find yourself in a situation where any of these dress codes is required, come into the Career Center or consult the internet for help. Note: You’ll notice that some of the pieces of clothing appear in multiple sections, and of course there are more options than what’s shown here. -

Dress Code Guidelines Freshman Leadership Program Seminar

Dress Code Guidelines Freshman Leadership Program Seminar Featuring Examples by Nick Quinn and Lauren Steier Casual – The most relaxed form of dress code. Men and Women: ClCasual is whthat you wear on an everyday basis, and encompasses nearly everything. Shorts, jeans, sweatpants, t‐shirts, or similar items are acceptable. *I won’t use this for FLP seminars. Smart Casual –Casual, but smart. Women: Similar to casual, but more presentable. Nice jeans, solid color or plaid shorts or pants (no athletic shorts), nice t‐shirts or tops are all acceptable. Tops should not be low cut and should cover to waist. No sweatpants, spaghetti‐string tops, short shorts, etc. Men: Similar to casual, but more presentable. Nice jeans, solid color or plaid shorts or pants, nice t‐shirts or polos are all acceptable. No sweatpants, athletic shorts, tank tops, etc. Business Casual – Casual dress that is acceptable in a business workplace (typical). Women: This is what you are most likely to encounter in the real‐world worklkplace. Wear nice pants or a skirt and an appropriate top. Should hit between smart casual and business formal. There is room for a lot of flexibility here. Men: This is what you are most likely to encounter in the real‐world workplace. Dress pants are the norm, usually khaki, but black or grey will work as well. Match the shoes to the pants (so brown with khaki, black with black or ggy)rey) and have a sock color that is the same color as you pants or darker. Your belt should be the same color as your shoes. -

The Commonwealth Club Dress Code

The Commonwealth Club Dress Code The Commonwealth Club was founded in CLUB AREAS AND APPLICABLE DRESS CODE Canberra for Members to enjoy the social benefits of association with like-minded people. Formal Dining Area: Formal or Business attire/ Semi Formal for both Men and Women. The General Committee requires Members and Children should also be dressed at a similar their guests to be presentably dressed in a standard. manner consistent with the character and Garden Room Dining, Lounge and Balcony standing of the Club. Areas: Business attire/Semi Formal or Smart Casual, dress denim (not blue) for both men DEFINITION OF MINIMUM STANDARD and women. DRESS CODES Formal, National Dress and Military Uniform is FORMAL acceptable throughout the Club at any time. Men: Lounge suit and tie, dress shoes. Club Accommodation: When entering and Women: Dress to reflect the formality of the leaving the Club accommodation, members and occasion, dresses, tailored trousers and skirts. guests may wear neat casual, including blue Men and Women: National Dress and Military denim and sports clothing. Uniform. Club Functions: Each Club function will specify which dress code is applicable. BUSINESS ATTIRE/SEMI-FORMAL Men: Lounge suit or trousers and jacket, Private functions: dress code is at the collared long sleeve shirt tucked in, tie required. discretion of the host, within Club Standards. Women: Trousers, suits, dresses, skirts and Members and guests whose dress does not jackets. meet the requirements listed above may be denied use of the clubhouse and sporting SMART CASUAL facilities. Management and staff are instructed Men: Trousers including chinos, coloured denim to advise members and guests if their dress is (not blue), collared shirt (long or short sleeve inappropriate tucked in), polo shirts without dominant logo.