The Design for the Initial Drainage of the Great Level of the Fens: an Historical Whodunit in Three Parts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Traveller Movement in Britain

Irish Traveller Movement in Britain The Resource Centre, 356 Holloway Road, London N7 6PA Tel: 020 7607 2002 Fax: 020 7607 2005 [email protected] www.irishtraveller.org Gypsy and Traveller population in England and the 2011 Census An Irish Traveller Movement in Britain Report August 2013 About ITMB: The Irish Traveller Movement in Britain (ITMB) was established in 1999 and is a leading national policy and voice charity, working to raise the capacity and social inclusion of the Traveller communities in Britain. ITMB act as a bridge builder bringing the Traveller communities, service providers and policy makers together, stimulating debate and promoting forward-looking strategies to promote increased race equality, civic engagement, inclusion, service provision and community cohesion. For further information about ITMB visit www.irishtraveller.org.uk 1. Introduction and background In December last year, the first ever census figures for the population of Gypsies and Irish Travellers in England and Wales were released. In all 54,895 Gypsies and Irish Travellers in England and 2,785 in Wales were counted.1 While the Census population is considerably less than previous estimates of 150,000-300,000 it is important to acknowledge that tens of thousands of community members did identify as Gypsies and Travellers. In the absence of a robust figure as a comparator to the census, the ITMB undertook research to estimate a minimum population for Gypsies and Travellers in England, based on Local Authority Gypsy and Traveller Accommodation Assessments (GTAA)2 and the Department for Communities and Local Government bi-annual Caravan Count. Definitions of Gypsies and Travellers For the purposes of this report it is important to understand the varying definitions of Gypsies, Irish Travellers and other Travelling groups in official data sources. -

T He Scottish Soldiers, the Ouse Washes; the Origins of Landscape Change in the Fens

Origins T he Scottish Soldiers, the Ouse Washes; the Origins of Landscape Change in the Fens by The Word Garden i Fen Islands Before the Drains Came ii iii First published 2019 Origins The Scottish Soldiers, the Ouse Washes; the Origins of Landscape Change in the Fens ©The Word Garden ISBN: 978-1-5272-4727-7 Copyright of individual authors rests with authors, pictorial map with artist, images with photographers and illustrator, and other rights holders as cited in the acknowledgements on pages 12-13, which constitute an extension of this copyright page. Publication design and layout by Helena g Anderson and Karen Jinks Front & back covers & interleaved images by Helena g Anderson Printed by Altone Ltd, Sawston, Cambridge Supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund LEGAL NOTICE All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the copyright holders. CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 2 - Historical, archival and scientificresearch 2 - Socio-cultural aspects of landscape change 2 2. THE TEAM 4 3. THE WORD GARDEN METHODOLOGY 5 4. ACHIEVEMENTS AND BENEFITS 6 - Public events 7 - Information Day 7 - Community Drop-in Open Day 7 - Local History Fair 7 - Schools workshop activities 7 - Mepal and Witcham Church of England Primary School 7 - Manea Community Primary School 7 - Two-day workshop at Welney Wetland Centre 29th and 30th June 8 - Map: Fen Islands Before The Drains Came by John Lyons 8 - The Play: The Scottish Soldier by Peter Daldorph, based on historical research 9 - The Film: From Dunure to Denver, Coventina’s Quest into Hidden History by Jean Rees-Lyons 10 - Project Godwit, Welney Wetland Centre 11 5. -

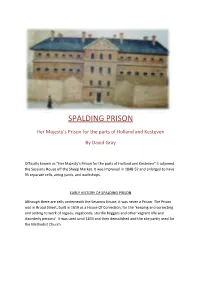

Spalding Prison

SPALDING PRISON Her Majesty’s Prison for the parts of Holland and Kesteven By David Gray Officially known as “Her Majesty’s Prison for the parts of Holland and Kesteven” it adjoined the Sessions House off the Sheep Market. It was improved in 1848-52 and enlarged to have 95 separate cells, airing yards, and workshops. EARLY HISTORY OF SPALDING PRISON Although there are cells underneath the Sessions House, it was never a Prison. The Prison was in Broad Street, built in 1619 as a House Of Correction, for the ‘keeping and correcting and setting to work of rogues, vagabonds, sturdie beggars and other vagrant idle and disorderly persons’. It was used until 1834 and then demolished and the site partly used for the Methodist Church. SPALDING PRISON IN THE SHEEP MARKET A new Prison was built next to the Sessions House in the Sheep Market, which was completed in 1836. It had all the conveniences, a human treadmill for the prisoners to walk on to grind their own flour, lots of cells for solitary confinement and 48 sleeping cells and a Chapel. Human Treadmill similar to the one that would have been used in the Prison Executions took place publicly in Spalding Market Place. The last man to be hung was in 1742, and his body afterwards “Gibbeted”, (hung in chains) on Vernat’s Bank. Spalding also used Stocks (heavy timber frame with holes for confining the ankles and sometimes the wrists) and a Pillory (a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands) , and a Tumbril (a two- wheeled cart that tipped up, used to transport prisoners) . -

Public Notices H.M

1630 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 4TH MARCH 1960 The East Midlands General .Review Area comprises including the boundaries of any such administrative the following administrative counties and county county or county borough with the following adminis-- boroughs— trative counties— Administrative counties Buckingham, Derby, Essex, Hertfordshire, Lin- Bedford, Cambridge, Huntingdon, Isle of Ely, coln, Parts of Holland, Lincoln, Parts of Kesteven, Leicester, Northampton, Rutland, Soke of Peter- (Norfolk, Nottingham, Oxford, Stafford, Warwick, borough. West Suffolk and such county district boundaries as coincide with County boroughs those county and county borough boundaries. Leicester; Northampton /. D. Jones, Secretary. PUBLIC NOTICES H.M. LAND REGISTRY T9i« following land is about to be registered-. Any (24) "The Gnoman," Cuttinglye Road, Crawley objections should be addressed to " H.'M. Land Regis- Downs, Worth, Sussex, by A. F. Allen, 5- Essex try, 'Lincoln's Inn Fields, London W.C.2 " before 18th Court, The Temple, London E.C.4. March I960. (25) The Dower House and land adjoining, Oxon Heath, near Tonbridge, Kent, by M. V. Bowater FREEHOLD of that address. (1) 3-35 (odd) and 6-34 (except 26) (even) Fentons (26) Upper Runham (Farm, Harrietsham, Kent, by Avenue and 12 and 16 and land at rear of 10-16 D. S. & M. S. A. 'Wilson of that address. (even) Greengate Street, Plaistow, London E.I3, (27) 79 Anerley 'Road, Anerley, (London S.E.20," by by M. J. -Bruce, 66 Gloucester Place, Portman D. Inwald, 21 iHigh IRoad, 'Kilburn. London (Square, (London, W.1, and E. Gray, 91 Mont- NjW.6. pelier Road, Hove, Sussex. (28) 7 and 9 Glenthorne Road, Friern Bamet, Middx, (2) 'Land adjoining the " Golden Lion " Public House, by F. -

English Hundred-Names

l LUNDS UNIVERSITETS ARSSKRIFT. N. F. Avd. 1. Bd 30. Nr 1. ,~ ,j .11 . i ~ .l i THE jl; ENGLISH HUNDRED-NAMES BY oL 0 f S. AND ER SON , LUND PHINTED BY HAKAN DHLSSON I 934 The English Hundred-Names xvn It does not fall within the scope of the present study to enter on the details of the theories advanced; there are points that are still controversial, and some aspects of the question may repay further study. It is hoped that the etymological investigation of the hundred-names undertaken in the following pages will, Introduction. when completed, furnish a starting-point for the discussion of some of the problems connected with the origin of the hundred. 1. Scope and Aim. Terminology Discussed. The following chapters will be devoted to the discussion of some The local divisions known as hundreds though now practi aspects of the system as actually in existence, which have some cally obsolete played an important part in judicial administration bearing on the questions discussed in the etymological part, and in the Middle Ages. The hundredal system as a wbole is first to some general remarks on hundred-names and the like as shown in detail in Domesday - with the exception of some embodied in the material now collected. counties and smaller areas -- but is known to have existed about THE HUNDRED. a hundred and fifty years earlier. The hundred is mentioned in the laws of Edmund (940-6),' but no earlier evidence for its The hundred, it is generally admitted, is in theory at least a existence has been found. -

The London Gazette, 23 December, 1919 K893

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 23 DECEMBER, 1919 K893 DISEASES OF ANIMALS ACTS, 1894 TO 1914 RETURN of OUTBREAKS of SWINE FEVER for the Week ended 20th December, 1919. Swine Swine slaughtered slaughtered as diseased as diseased Counties (including all Outbreaks or as having Counties (including all Outbreaks or as having Boroughs therein*), i, Confirmed. been ex- Boroughs therein*). Confirmed. been ex- posed to ! • • p:>3ed to . infection. infection ENGLAND. Nr. Mo. ENGLAND. (No. No. Buckingham 1 Northampton ... 1 • » » Cambridge 2 'i • Soke of Peterborough 1 Isle of Ely 3 ... Notts 1 ... Derby 1 •••• Oxford 2 2 Dorset 1 • •• Somerset 1 • • • Durham I • • * Suffolk 2 ... Gloucester 1 1 Warwick 1 . »j- Lincoln, Parts of Holland 1 ... York, East Riding 1 . .. „ „ Kesteven 1 ... „ North „ 2 ... „ " „ Lindscy 1 1 „ West ,, '1 ... Norfolk 6 . 3 TOTAL _ 33 8 V * For convenience Berwick-upon-Tweed- is considered to be in Northumberland, Dudley in Worcestershire, Stockport in Cheshire, and the city of London in the county of London. NOTE.—The term, "administrative county " used in the following descriptions of Areas is the district for which a county council is elected under the Local Government Act, 1888, am? includes all boroughs in it which are not county boroughs. The following Areas are now " Infected Areas " for the purposes of the Swine-Fever (Regulation of Movement) Order of 1908: — Huntingdon.—An Area, in the administrative Nottingham.—An Area in the administrative county of Huntingdon, comprising the county of Nottingham, comprising the petty sessional division of Ramsey (excluding borough of Mansfield, and the parishes of its detached part) (24 November, 1919.) Mansfield Woodhouse, Sutton-in-Ashfield, Isle of Ely.—An Area comprising the borough Kirkby-in-Ashfield, Fulwood, Hucknall- of Wisbech, the petty sessional divisions of under-Huthwaite, Teversall, and Skegby Whittlesley, and Wisbech (except the (2 July, 1919). -

Cromwelliana

Cromwelliana The Journal of The Cromwell Association 2017 The Cromwell Association President: Professor PETER GAUNT, PhD, FRHistS Vice Presidents: PAT BARNES Rt Hon FRANK DOBSON, PC Rt Hon STEPHEN DORRELL, PC Dr PATRICK LITTLE, PhD, FRHistS Professor JOHN MORRILL, DPhil, FBA, FRHistS Rt Hon the LORD NASEBY, PC Dr STEPHEN K. ROBERTS, PhD, FSA, FRHistS Professor BLAIR WORDEN, FBA Chairman: JOHN GOLDSMITH Honorary Secretary: JOHN NEWLAND Honorary Treasurer: GEOFFREY BUSH Membership Officer PAUL ROBBINS The Cromwell Association was formed in 1937 and is a registered charity (reg no. 1132954). The purpose of the Association is to advance the education of the public in both the life and legacy of Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), politician, soldier and statesman, and the wider history of the seventeenth century. The Association seeks to progress its aims in the following ways: campaigns for the preservation and conservation of buildings and sites relevant to Cromwell commissions, on behalf of the Association, or in collaboration with others, plaques, panels and monuments at sites associated with Cromwell supports the Cromwell Museum and the Cromwell Collection in Huntingdon provides, within the competence of the Association, advice to the media on all matters relating to the period encourages interest in the period in all phases of formal education by the publication of reading lists, information and teachers’ guidance publishes news and information about the period, including an annual journal and regular newsletters organises an annual service, day schools, conferences, lectures, exhibitions and other educational events provides a web-based resource for researchers in the period including school students, genealogists and interested parties offers, from time to time grants, awards and prizes to individuals and organisations working towards the objectives stated above. -

The London Gazette, March 11, 1902

1748 THE LONDON GAZETTE, MARCH 11, 1902. DISEASES OF ANIMALS ACTS, 1894 AND 1896—continued. Staffordshire.— (1.) An Area comprising tee petty SWINE-FEVER INFECTED AREAS—cont. sessional divisions of Rushall and Hand worth, in the administrative county of Stafford ; and also comprising the boroughs of Walsall, Wed- divisions of Epping, Beacon tree, and Romford, nesbury, West Bromwich, and Smethwick (29 in the administrative county of Essex (22 Avgust, 1901). January, 1902). (2.) An Area comprising the petty sessional Gloucester shirf.—An Area comprising the petty divisions of Rngeley, and Lichfield and Brown- sessional divisions of Whitminster, Stroud hills, and the borough of Lichfield, in the ad- (except tlie parish of Cranham), Nailsworth, ministrative county of Stafford (11 February, and Dursiey, and the parishes of Harescombe and Cherrington, in the administrative county of Gloucester (5 March, 1902). Surrey. — An Area comprising the administrative county of Surrey, including the boroughs of Hampshire —An Area eompiising the parishes of Guildford, Kingston upon-Thames. Reigate, Burley, Rhinefield, Brockenhurst, and Ljnd- Richmond, ai>d Godalming ; and also compris- hurst, in the administrative county of South- ing the borough of Croydon (3 March, 1902). ampton (30 December, 1901). — An Area comprising the petty sessional See also under Berkshire and Hampshire. divisions of Bittle (except the paiish of Ewhurst), and Hastings (including the two Hertfordshire and Middlesex.—An Area compris- ^etaclied parts theivof, namely, the parish of -

The London Gazette, Apeil 10, 1883. 1905

THE LONDON GAZETTE, APEIL 10, 1883. 1905 (2.) So much of the borough of Over from Chapel Bridge to the Back-lane near Mr. Darwen, in the county of Lancaster, as lies Bettinson's farm-house on the west, thence the within the following boundaries, that is to say, Back-lane to the Roman Bank near Mr. Stephen the boundary line of the borough from Set Moyer's house and the Roman Bank to and End to G-oose House Bridge on the east and along Mr. John Brown's occupation - road north, the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway passing Monmouth House to the Road's End from Groose House Bridge to the Bridge over on the north, thence a du'ect imaginary line the Railway near Greenfield on the west, the across lands in the occupation of Mr. John road leading over the last-mentioned Bridge Brown and Mr. J. W. Wadeson to Wood-lane past Lower Barn to Blacksnape, Blacksnape- and over such lane and across lands in the road to Davy Fold, the road from Davy Fold occupation of Mr. R. Roberts and Mr. R. through Hoddlesden and Falten Houses to the Winfrey to the Sutton Bridge highway near eastern boundary of the borough, and such Mr. Thomas Naylor's farm-buildings on the boundary to its junction with Blacksnape-road east, and thence the Sutton Bridge highway near Set End on on the south. through Long Sutton town to Chapel Bridge (3.) The whole of the borough of Wigan, aforesaid on the south ; exclusive of all boun- in the county of Lancaster, dary-roads but inclusive of all intersecling- (4.) The whole of the borough of Over roads. -

LINCOLNSHIRE (Parts of HOLLAND)

LINCOLNSHIRE (Parts of HOLLAND) Holland was the smallest of the three Parts into which Lincolnshire was traditionally divided. It was bordered to the west by the Parts of Kesteven, to the north by the Parts of Lindsey, and to the east by the North Sea. To the south, the adjacent counties were Rutland, Cambridgeshire and Norfolk. Holland consisted of three wapentakes, Skirbeck, Kirton and Elloe. At certain times and for certain purposes, the first two were combined in the administrative region of North Holland, while Elloe was known as South Holland. The announcement of the weights and measures in 1826 came from the single authority for Holland. In 1857, a unified police force for the whole of Lincolnshire was established, with officers moving between the Parts, and the inspection of weights and measures became its responsibility. The ancient boroughs of Boston and Spalding had separate jurisdiction. There is little evidence of activity in Spalding, where the county inspector for Elloe lived, and the authority officially took over in 1862. Boston remained a separate authority until the great reorganisation of 1974. It was the centre for numerous commercial activities, and the trade in scales and weights flourished there. A: Inspection by the County of LINCOLNSHIRE (Parts of HOLLAND) Dates Events Marks Comments 1795 3 wapentakes: Elloe, Kirton, Skirbeck. In the early 19th century there were two divisions with separate administrations: North Holland 1825 One set of standards [186] = Kirton and Skirbeck, South verified. Holland = Elloe. Inspectors 1826-62: 1834 1826 inspectors continued in Elloe: office, 4 being appointed for 1826 Thos King, Thomas Pick Kirton & Skirbeck, 2 for Elloe; 1834 Thos. -

Fenland District Wide Local Plan Chatteris Adopted August 1993 ______

Fenland District Wide Local Plan Chatteris Adopted August 1993 _______________________________________________________________________________________ CHATTERIS Inset Proposals Map No. 2a and 2b 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. This section contains the detailed planning background, policies and proposals for Chatteris. It must be read in conjunction with the general policies set out in Part One of the Local Plan. 2. LOCATION 2.1. Chatteris lies in the south of the District and is situated at the junction of the A141 between Huntingdon and March and the A142 to Ely. Chatteris is approximately seven miles south of March, thirteen miles from Huntingdon and thirteen miles from Ely. 3. HISTORY 3.1. Chatteris stands on an island of higher ground surrounded by peat fen which is one of the richest agricultural areas in England. The intensive arable farming is based on the immensely fertile black fen soil which was brought under cultivation progressively over the centuries by drainage schemes of which the most notable and spectacular are the Old and New Hundred Foot Rivers. These were constructed by the Dutch Engineer, Cornelius Vermuyden in the mid 17th century. 3.2. The growth of Chatteris has primarily been related to local agriculture, especially the production of root crops, and in more recent times to agricultural related industries, in particular processing and packing. However with the implementation of the Fen Link Roads programme, Chatteris is now accessible to wider areas of employment and is experiencing different pressures for growth from those who work in Cambridge and the Ouse Valley corridor. 3.3. The oldest surviving buildings in the town are principally on the High Street/Market Hill area with the Church of St. -

Fenland Field Trip

RIVER AND WATER MANAGEMENT IN THE FENLAND The Fenland is a landscape that reflects the interplay between environmental and social processes over centuries. This field excursion will examine the initial formation of the Fenland region, the draining of the Fens, and contemporary water management in the Fens, and will provide a useful background for the session on multi-purpose water management tomorrow, in which we consider institutional partnerships at the local scale. The landscape “When the spring tides flood into the Wash and run up the embanked lower courses of the Witham, Welland, Nene and Great Ouse, more than [3,100 km2] of Fenland lie below the level of the water” (Grove, 1962, p.104). The Fenland is one of the most distinctive landscapes of Britain, maintained as a largely agricultural region as a result of embankment, drainage and sophisticated and complex river and water management similar to that most often associated with the Netherlands. Its uniqueness is captured in one of the great British novels of the last fifty years, Waterland by Graham Swift. The creation of this landscape began with reclamation and embankment in Roman Times, but was mostly achieved in the seventeenth century with the assistance of Dutch engineers. Cambridge itself is just south of the southern edge of the Fens, but the banks of the River Cam just NE of the city are only at 4.0-4.5m OD, although about 50km from the sea. The basic framework: geology and topography In the early post-glacial period, about 10,000 years ago, the sea stood over 30m lower than now, and the Fenland basin was drained by a system of rivers (early versions of the Cam, Ouse, and Nene) that reached a shrunken North Sea by a broad, shallow valley trending NE between Chalk escarpments in Lincolnshire and Norfolk.