Transition Illawarra Initiative: Report Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’S Guide

New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’s Guide Important: This Operator’s Guide is for three Notices separated by Part A, Part B and Part C. Please read sections carefully as separate conditions may apply. For enquiries about roads and restrictions listed in this document please contact Transport for NSW Road Access unit: [email protected] 27 October 2020 New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’s Guide Contents Purpose ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Definitions ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 NSW Travel Zones .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Part A – NSW Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicles Notice ................................................................................................ 9 About the Notice ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 1: Travel Conditions ................................................................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Pilot and Escort Requirements .......................................................................................................................... -

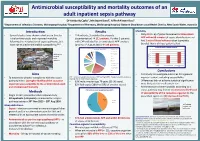

Introduction Aims Methods Results Conclusions

Antimicrobial susceptibility and mortality outcomes of an adult inpatient sepsis pathway Dr Kimberly Cipko1, Mr Stuart Bond2, A/Prof Alistair Reid1 1Department of Infectious Diseases, Wollongong Hospital; 2Department of Pharmacy, Wollongong Hospital, Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District, New South Wales, Australia Introduction Results Mortality • Several studies have shown reductions in time to • 114 patients, 3 excluded (inadequate • Only 6% (n=6) of patients received antimicrobials initial antimicrobials and improved mortality documentation) 111 patients. Further 5 patients APP within 60 minutes of sepsis identification and following the introduction of sepsis pathways, but with CAP excluded for ‘antimicrobials APP’ analysis had 2 sets of blood cultures taken (complete have not studied antimicrobial susceptibility.1,2,3 (prior to 1st August 2016) 106 patients. bundle). None of those patients died. 30-day all-cause in hospital mortality Source of sepsis (%) Unkown origin 35 HAP low MRO 30 4 111 25 Wollongong 6 HAP high MRO 20 Hospital 5 CAP 33 15 NSW, Urine % mortality % mortality 10 Australia 9 Biliary/GI 5 Skin/surgical site 0 5 Diabetic foot Overall Antimicrobials APP Antimicrobials not APP Peri/postpartum 13 Other 23 Conclusions Neuro Aims • First study to investigate outcomes for a general CAP – community acquired pneumonia; HAP low/high MRO – Hospital acquired pneumonia inpatient cohort, including susceptibility. • To determine whether compliance with the sepsis low/high risk of multi-resistant organisms pathway led to: (1) Higher likelihood the causative • 63% male; median age 76 years (21-96 years). • Differences did not achieve statistical significance – organism was susceptible to the antimicrobials used • 82% had sepsis (18% had SIRS of another cause). -

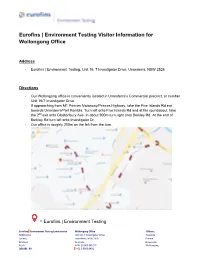

Environment Testing Visitor Information for Wollongong Office

Eurofins | Environment Testing Visitor Information for Wollongong Office Address - Eurofins | Environment Testing, Unit 16, 7 Investigator Drive, Unanderra, NSW 2526 Directions - Our Wollongong office is conveniently located in Unanderra’s Commercial precinct, at number Unit 16/7 Investigator Drive. - If approaching from M1 Princes Motorway/Princes Highway, take the Five Islands Rd exit towards Unanderra/Port Kembla. Turn left onto Five Islands Rd and at the roundabout, take the 2nd exit onto Glastonbury Ave. In about 900m turn right onto Berkley Rd. At the end of Berkley Rd turn left onto Investigator Dr. - Our office is roughly 200m on the left from the turn. = Eurofins | Environment Testing Eurofins Environment Testing Laboratories Wollongong Office Offices : Melbourne Unit 16, 7 Investigator Drive Adelaide Sydney Unanderra, NSW 2526 Darwin Brisbane Australia Newcastle Perth ABN: 50 005 085 521 Wollongong QS1081_R0 +61 2 9900 8492 Parking - There are 3 car spaces directly in front of the building, if the spaces are all occupied there is also on street parking out the front of the complex. General Information - The Wollongong office site includes a client services room available 24 hours / 7 days a week for clients to drop off samples and / or pick up bottles and stock. This facility available for Eurofins | Environment Testing clients, is accessed via a coded lock. For information on the code and how to utilize this access service, please contact Elvis Dsouza on 0447 584 487. - Standard office opening hours are between 8.30am to 5.00pm, Monday to Friday (excluding public holidays). We look forward to your visit. Eurofins | Environment Testing Management & Staff Eurofins Environment Testing Laboratories Wollongong Office Offices : Melbourne Unit 16, 7 Investigator Drive Adelaide Sydney Unanderra, NSW 2526 Darwin Brisbane Australia Newcastle Perth ABN: 50 005 085 521 Wollongong QS1081_R0 +61 2 9900 8492 . -

Masterplan LAND ESTATE W

EDUCATION 1 The Little School Pre School 2 min 1km 2 Dapto Public School 8 min 7km 3 Mount Kembla Public School 15 min 12.6km 4 Kanahooka High School 7 min 5.8km 5 Illawarra Sports High School 10 min 9.2km 6 Dapto High School 9 min 6.3km 7 Five Islands Secondary College 18 min 4.6km 8 University of Wollongong 13 min 15.1km 9 TAFE Illawarra Wollongong Campus 14 min 15.7km RETAIL 1 Wollongong Central 15 min 14.9km 2 Figtree Grove Shopping Centre 11 min 10.1km 3 Dapto Mall 5 min 4.9km 4 Shellharbour Village 22 min 21.3km 5 Shellharbour Square Shopping Centre 22 min 18.5km 6 Shell Cove 20 min 20km (with Marina under construction) HEALTH 1 Wollongong Hospital 13 min 14km 2 Wollongong Private Hospital 13 min 13.7km 3 Dapto Medical Centre 5 min 4.9km 4 Illawarra HealthCare Centre 4 min 3.8km 5 Illawarra Medical Services 9 min 8.4km 6 Illawarra Area Health Service 15 min 15.4km 7 Lotus Wellbeing Centre 18 min 16.6km RECREATION 1 Kembla Grange Racecourse 5 min 4.5km 2 Fox Karting Centre 5 min 4.9km 3 The Grange Golf Club 6 min 5.3km 4 Ian McLennan Park 5 min 4.8km 5 Berkeley Youth & Recreation Centre 9 min 7.8km 6 Wollongong Surf Leisure Resort 16 min 19.5km 7 Windang Bowling Club 19 min 18.1km 8 Lake Illawarra Yacht Club 11 min 10.5km 9 Port Kembla Beach 16 min 16km 10 WIN Stadium 16 min 16km 11 WIN Entertainment Centre 17 min 16.9km 12 Jamberoo Action Park 22 min 20.7km 13 Wollongong Golf Club 18 min 17km 14 Killalea State Park 23 min 21.7km TRANSPORT 1 Kembla Grange Train Station 4 min 4.2km 2 Dapto Train Station 6 min 5.1km 3 Unanderra Train Station 9 min 8km 4 Coniston Train Station 14 min 15.1km 5 Wollongong Train Station 16 min 16.5km Stockland Shellharbour Shopping Centre University of Wollongong Nan Tien Temple City of Wollongong Proudly marketed by: Simon Hagarty - Sales Manager REGISTER HERE: C 0405 175 416 BRAND NEW E [email protected] Masterplan LAND ESTATE www.KemblaGrangeEstate.com.au W www.ulh.com.au Disclaimer: This is a sales plan only. -

View in Website Mode

90 bus time schedule & line map 90 Austinmer Station View In Website Mode The 90 bus line (Austinmer Station) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Austinmer Station: 4:55 AM - 10:10 PM (2) Fairy Meadow: 10:50 PM (3) George St & Lawrence Hargrave Dr: 11:00 PM - 11:30 PM (4) Wollongong Entertainment Centre: 5:20 AM - 9:50 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 90 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 90 bus arriving. Direction: Austinmer Station 90 bus Time Schedule 57 stops Austinmer Station Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 8:25 AM - 7:25 PM Monday 4:55 AM - 10:10 PM WIN Entertainment Centre, Crown St 10 Crown Street, Wollongong Tuesday 4:55 AM - 10:10 PM Burelli St at Harbour St Wednesday 4:55 AM - 10:10 PM 5 Burelli Street, Wollongong Thursday 4:55 AM - 10:10 PM Wollongong City Council And Library, Burelli St Friday 4:55 AM - 10:30 PM 41 Burelli Street, Wollongong Saturday 6:35 AM - 10:30 PM Wollongong Central, Burelli St, Stand B Burelli Street, Wollongong Wollongong Central, Kiera St, Stand G 220-224 Crown Street, Wollongong 90 bus Info Direction: Austinmer Station Keira St at Victoria St Stops: 57 136 Keira Street, Wollongong Trip Duration: 43 min Line Summary: WIN Entertainment Centre, Crown St, Collegians Club, Flinders St Burelli St at Harbour St, Wollongong City Council And Princes Highway, Wollongong Library, Burelli St, Wollongong Central, Burelli St, Stand B, Wollongong Central, Kiera St, Stand G, Keira Flinders St after Gipps St St at Victoria St, Collegians Club, Flinders -

Illawarra & Shoalhaven Sexual Health & Blood Borne Infections Directory

Illawarra & Shoalhaven Sexual Health & Blood Borne Infections Directory Intention of the directory: What is sexual health? According to the World Health Organisation sexual health is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity, but rather, sexual health includes a holistic state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being. As such, sexual health requires a respectful approach to sexuality and relationships, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. Who is HARP? The HARP Health promotion team promote prevention, early intervention, treatment and management of HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis C and Sexually Transmitted Infections. The HIV and Related Programmes Unit (HARP) activity is guided by National, State and Local Health District strategies that aims to improve sexual health and reduce the harm associated with Sexually Transmissible Infections (STIs), HIV and Hepatitis C. The HARP team partner with community organisations who engage and represent people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds (CALD), young people, Aboriginal people, sex workers, gay men, men who have sex with men (MSM), people living with HIV, people who inject drugs, and heterosexuals with a recent change in partner. HARP provide a range of free resources, work in collaboration with partner organisations on projects and develop awareness raising and capacity building training sessions. What is the intention of HARP? Our intention is to create a positive environment in which the community feel comfortable to approach the issues of HIV, STIs and Blood Borne Infections (BBIs) and acknowledge the realities of their impact both within our own communities and globally. We work towards creating an environment where HIV, STIs and BBIs can be discussed, accepted and ultimately prevented without fear, myth, stigma or discrimination. -

S203 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

S203 bus time schedule & line map S203 Bellevue Rd at Princes Hwy to St Marys College View In Website Mode The S203 bus line (Bellevue Rd at Princes Hwy to St Marys College) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) St Marys: 7:45 AM (2) West Wollongong: 3:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest S203 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next S203 bus arriving. Direction: St Marys S203 bus Time Schedule 42 stops St Marys Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Bellevue Rd at Princes Hwy 3 Bellevue Road, Figtree Tuesday 7:45 AM Bellevue Rd opp Edgebury Rd Wednesday 7:45 AM 55 Bellevue Road, Figtree Thursday Not Operational Bellevue Rd at Stillness Rd Friday Not Operational Bellevue Road, West Wollongong Saturday Not Operational Uralba St opp Zelang Av 56 Uralba Street, West Wollongong Uralba St at Walang Av 26 Uralba Street, West Wollongong S203 bus Info Direction: St Marys Walang Av at Kilbirnie Pl Stops: 42 12 Walang Avenue, West Wollongong Trip Duration: 30 min Line Summary: Bellevue Rd at Princes Hwy, Bellevue Walang Av before Kilbirnie Pl Rd opp Edgebury Rd, Bellevue Rd at Stillness Rd, 26 Walang Avenue, West Wollongong Uralba St opp Zelang Av, Uralba St at Walang Av, Walang Av at Kilbirnie Pl, Walang Av before Kilbirnie Koloona Av after Walang Av Pl, Koloona Av after Walang Av, Koloona Av at St 28 Koloona Avenue, West Wollongong Marks Cres, Koloona Av at Valley Dr, Carcoola St after Koloona Av, Euroka St after Immarna Av, Koloona Av at St Marks Cres Euroka -

Dark Dragon Ridge: Chinese People in Wollongong, 1901-39 Peter Charles Gibson University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1954-2016 2014 Dark Dragon Ridge: Chinese people in Wollongong, 1901-39 Peter Charles Gibson University of Wollongong Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Gibson, Peter Charles, Dark Dragon Ridge: Chinese people in Wollongong, 1901-39, Master of Arts - Research thesis, School of Humanities and Social Inquiry, University of Wollongong, 2014. https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/4143 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Dark Dragon Ridge: Chinese People in Wollongong, 1901-39 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts (Research) from University of Wollongong by Peter Charles Gibson, BA (Wollongong) School of Humanities and Social Inquiry Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts 2014 I, Peter Charles Gibson, declare that this thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Master of Arts (Research), in the School of Humanities and Social Inquiry, University of Wollongong, is my own work unless otherwise acknowledged. It has not been submitted in whole or in part for a degree at this or any other institution. Peter Charles Gibson 18th of March 2014 Abstract This thesis sheds new light on Chinese people in Australia's past by examining Chinese in the town of Wollongong, on the New South Wales South Coast, between 1901 and 1939. -

CEO on CPRS SEV5 PDF 14.08.09

Attention ASX Company Announcements Platform Lodgement of Open Briefing ® Level 11, 120 Collins Street Melbourne, VIC 3000 Date of lodgement: 17-Aug-2009 Title: Open Briefing ®. BlueScope Steel. CEO on CPRS Record of interview: corporatefile.com.au What is BlueScope’s view of the current design of the CPRS? MD & CEO Paul O'Malley We support abatement of greenhouse gas emissions in a way that doesn’t impair the competitiveness of emissions-intensive trade-exposed industries. However, the current design of the CPRS will not achieve these objectives. Large potential costs not faced by our major competitors threaten the world competitiveness of our Australian iron and steelmaking operations. Maintaining our trade competitiveness is absolutely essential to the future of our Australian operations, from which we normally export about half of the steel production. In domestic markets we compete with imports, which face very few trade barriers. Future permit allocation arrangements are currently uncertain. This weighs heavily in assessing future investment in our Australian iron and steelmaking operations, including major capital expenditure for emissions abatement. We need confidence that there will be no adverse permit allocation changes for the Australian steel industry while our major competitors do not face comparable carbon costs. The CPRS as currently designed would operate as a compounding tax on a high For personal use only fixed cost and capital-intensive industry. 1 corporatefile.com.au What is the global situation with regard to carbon regulation and the steel industry? MD & CEO Paul O'Malley Australia manufactures about 0.6 per cent of the world’s steel. -

Grand Pacific Drive

Grand Pacific Drive Grand Pacific Drive OPEN IN MOBILE The scenic coastal drive along Sea Cliff Bridge, Clifton Details Open leg route 200.6KM / 124.7MI (Est. travel time 3 hours) From the rockpools and cliff-hugging rainforests to beaches and unspoilt marine parks, this journey offers a wealth of coastal drama. The PaciÊc Ocean is a constant, whether driving beside it or over it; exploring below the waves on dive expeditions, or above spotting whales and dolphins. And then there are the waterside bars, restaurants and wineries along the way. What is a QR code? To learn how to use QR codes refer to the last page 1 of 24 Grand Pacific Drive What is a QR code? To learn how to use QR codes refer to the last page 2 of 24 Grand Pacific Drive 1 Depart Sydney OPEN IN MOBILE Outside the Sydney Opera House in Circular Quay, Sydney GET DIRECTION S What is a QR code? To learn how to use QR codes refer to the last page 3 of 24 Grand Pacific Drive 2 Day 1: Royal National Park OPEN IN MOBILE Beaches, rainforest, waterfalls, rockpools, sheer cliÂs – this remarkable backdrop is just an hour south of Sydney. Australia’s oldest national park delivers 15,000 hectares of nature at its Ênest. Enjoy perspective at Governor Game Lookout. Your ocean vista is framed by native forest, a magnet for crimson rosellas and yellow-tailed black cockatoos. OÂshore you’ll spot migrating People swimming at Wattamolla, Royal National Park whales (May through November), with 25,000 traversing the country’s east coast annually. -

F6 Extension Stage 1

F6 Extension Stage 1 Submission from the Illawarra Business Chamber to Roads and Maritime Services Illawarra Business Chamber Level 1, 87-89 Market Street Wollongong NSW 2500 (p) (02) 4229 4722 (e) [email protected] 27 July 2018 F6 Extension Stage 1 2 Summary The Illawarra Business Chamber (IBC) welcomes the NSW Government’s commitment to commence Stage 1 works of the F6 Extension and the opportunity to provide feedback on this proposal. The IBC recognises that this consultation is focussed on the intended planning and delivery of Stage 1. Even so, this submission will highlight the benefits to be realised through bringing forward the planning and projected delivery of Stage 2 and Stage 3 works, and discuss the findings and projections detailed in the report Upgrading Road Connectivity Between the Illawarra and Greater Sydney (May 2018) commissioned by Illawarra First together with the NRMA and conducted by Veitch Lister Consulting (VLC), which in part addresses the F6 Extension. Key Findings The IBC notes the significant benefits to be realised through advancing the timings for the complete F6 Extension, in addition to concurrent infrastructure works. Key findings of this submission, consistent with the aforementioned report, highlight the need for government to consider the F6 project in its entirety, and as complementing other works: - Key Finding 1 Without intervention, congestion and travel times from the Illawarra to Greater Sydney will steadily increase and the cost of delays is estimated at $640 million per annum by 2031, impacting business and employment opportunities. - Key Finding 2 The F6 Extension Stage 1 will save commuters 6 minutes along the length of the new road, 12 minutes once Stages 2 and 3 are complete. -

POP up LEASING + ADVERTISING OPPORTUNITIES Make Your Brand POP up Stand out at LEASING Wollongong Central

WOLLONGONG CENTRAL POP UP LEASING + ADVERTISING OPPORTUNITIES Make your brand POP UP stand out at LEASING Wollongong Central Pop-up shops have proven to be a popular concept overseas over recent years and is an emerging trend in Australia used to build brand awareness, launch a new product or test a consumer market. Wollongong Central has various pop-up leasing sites, located in variety of key precincts across three buildings, providing you the opportunity to show case your product or service. Benefits of a pop-up store: . Access to a new audience: Pop-up space is a great way for you to take a product from online to real world or beyond the immediate catchment of your existing premises. Test a business idea: Pop-up space is a great way to test your product with less risk. Expand your market: Pop-up space is a great way to promote your brand name to a broader audience at mass, or target a specific new audience. WHY WOLLONGONG CENTRAL – ‘THE GONG’? HEART OF THE GONG Wollongong Central is located in the heart of Wollongong and is the only regional shopping centre located in its Main Trade Area. Servicing the community since 1975, Wollongong Central is home to Myer, Target, Coles, Rebel, JB Hi-Fi Home, Best & Less, Club Lime and over 220 leading specialty retailers. In late 2014, GPT completed a $200 million expansion of Wollongong Central, adding an additional 18,000sqm of new retail space over three levels. Introducing 80 new retailers, the redefined retail mix within each building and precinct showcases a dynamic range of great food-on-the- go, café and street-front dining options, sought-after fashion, contemporary home wares and cutting-edge technology from national and local brands.